AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

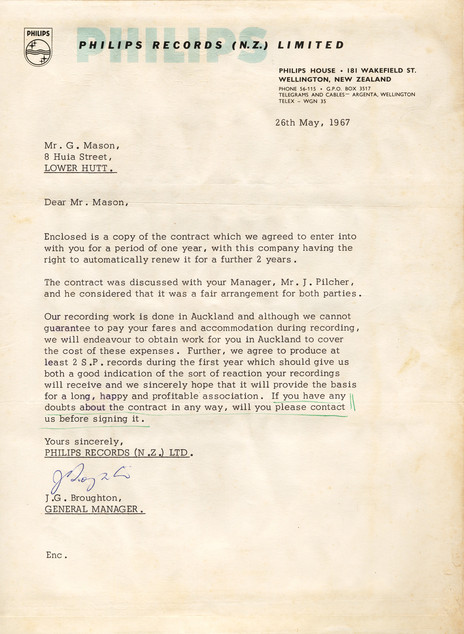

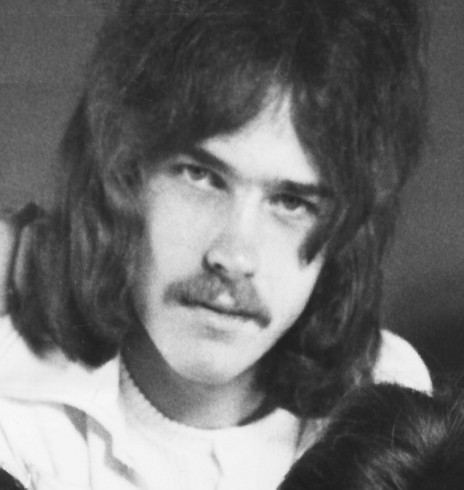

Glyn Mason

When Glyn was three they shifted to Australia, staying until 1958. That year they crossed the Tasman to New Zealand, moving around a few times before finally settling in Lower Hutt.

His parents came from an era when music was integral to people’s survival; the generation who had been through a war, through tough times. There was a need to keep joy and camaraderie up by doing things like singing in pubs, or anywhere they could. Glyn has childhood memories of being clad in pyjamas listening to singing at parties in the house. It wasn’t until he was at school that he began to participate in music.

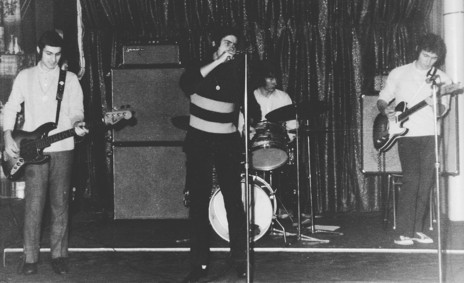

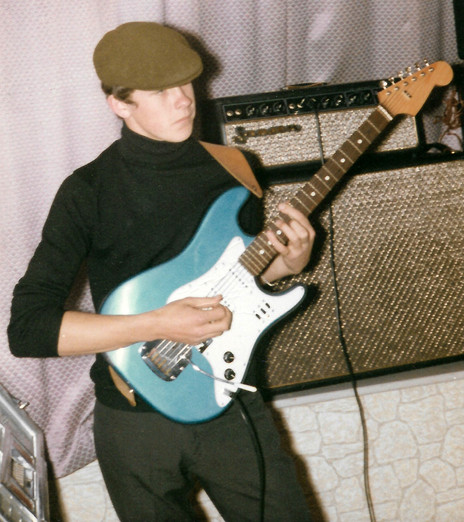

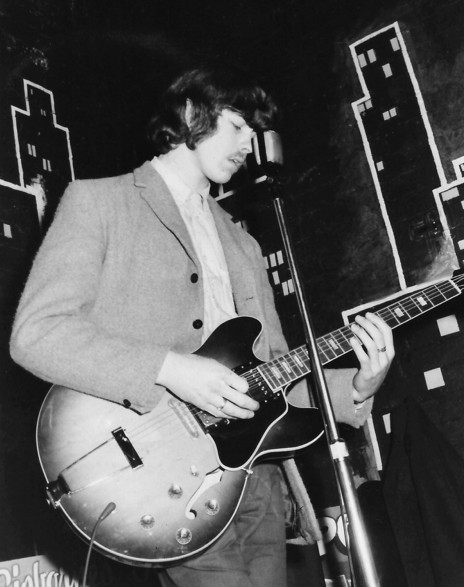

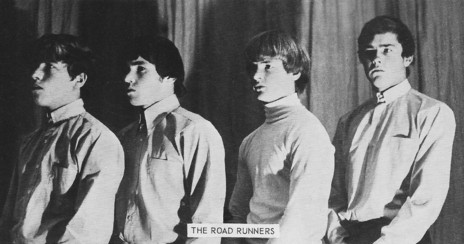

Fate or destiny struck again when he was a teenager. He went to high school with Chaz Burke-Kennedy, who taught him lots about playing guitar. Chaz formed a band at school that included Glyn. and was behind the formation of the Roadrunners in 1964. In his book When Rock Got Rolling, Roger Watkins observed that their vocal harmonies were becoming noticed, adding, “Chaz’s blistering guitar work was exciting interest among other musicians, as was Glyn’s harder-edged style. Together, they were extraordinarily talented.”

After high school Glyn attended Wellington Polytech to study art. He got through the first year, but in the second he needed to choose between industrial or graphic design. “My desire to play music was encouraged, along with the fact that I was bunking classes to go and play.” He knew he was wasting his parents’ hard-earned cash by not attending classes. “It was a great disappointment to my father.”

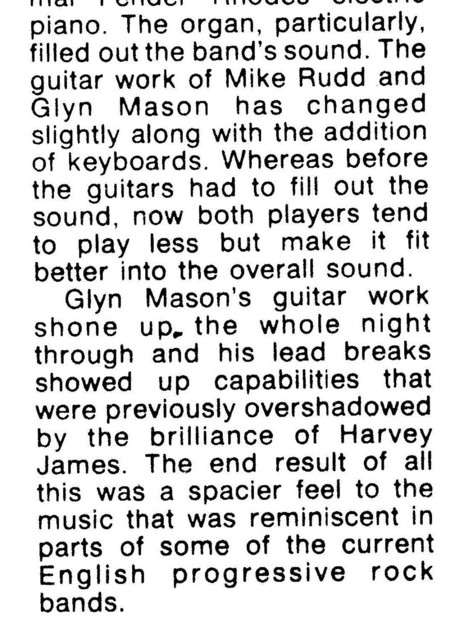

After the Roadrunners broke up, Glyn spent about nine months with The Bitter End, playing lead guitar before heading north following an invitation to join a new band. In Auckland in 1968 he helped form Jigsaw, which also featured Burke-Kennedy and is remembered as a soul band. Drummer Tony Walton was in this band as was George Barris, the third member from Wellington.

Next it was on to The Rebels. “I was in Auckland playing with a band called Jigsaw. In the world of musos back then there was more social activity. There was never the competitive world in real terms. We’d come down to their club. They’d come down to ours.

“Nooky [Nooky Stott, drummer with Larry’s Rebels] and Willy [John Williams, lead guitarist with Larry’s Rebels] came to the Galaxie. They just turned up one day and said ‘Larry is not with us any more. Do you want to join the band?’ And I said ‘I’m in a pretty good band now. Thanks guys. What are you doing?’”

With Glyn on board The Rebels recorded the album Madrigal. It and Glyn received great reviews.

They told Glyn they were recording an album, about to embark on a tour, and going back to Australia.

“They’d been here a few times before with Larry. They were very popular here. I was interested in their world. When they said they were doing an album I was interested. And they said ‘Do you write songs?’ and I said ‘Yeah, yeah.’ I was interested in following that path. They were highly successful. And when they said Australia ... it was highly unlikely that Jigsaw would be heading to Australia any time.”

With Glyn on board, The Rebels recorded the album Madrigal, which received great reviews. One reviewer noted, “Many would say that Glyn Mason sings even better than his predecessor.” Another wrote, “The most impressive thing about this first Rebels’ LP to come along since the departure of Larry Morris is the vocalising of new recruit Glyn Mason. No doubt about it, the boy can sing.”

Writing about Madrigal for AudioCulture, Nick Bollinger reported, “Their secret weapon is Morris’s replacement, Glyn Mason – a Wellington-bred singer with a mighty rhythm and blues voice like Steve Winwood crossed with Wilson Pickett.”

Of his time with The Rebels, Glyn said, “We wrote a few songs. And we also had a hit with ‘My Son John’ which was an English tune. It went to No.1 when I joined the band.

“I came back to Australia in 1969 with the Rebels, arrived March 30, 1969. When I arrived I think there was probably pretty much a Kiwi in every major act in Australia without a doubt. Especially in Victoria. There were truckloads.”

“On March 30 we went charging out on the town. We saw Doug Parkinson in Focus play and I left saying, ‘I don’t want to play another cover song’.” To write and perform originals was what Glyn wanted. “We tried really hard. The band became really proficient.”

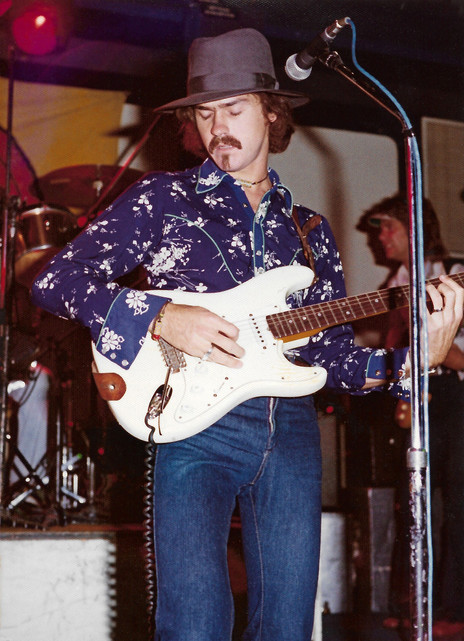

They got lots of work but after eight or nine months Viv McCarthy left to get married and the band broke up. Glyn: “I knew other people and I joined Chain and was with them for a year and a half. It was a lot of fun. Chain was playing heavy, straight blues. I wasn’t the greatest musician to join that band. My vocal has usually been enough to carry me through.”

Chain had formed in 1967. During 1969, when the band moved to Sydney, organist Claude Papesch (ex-Johnny Devlin and the Devils) and bassist Tim Piper (ex-Chants R&B) joined the line-up but left later the same year. Glyn joined Chain in January 1970, making the line-up a five piece with Phil Manning (guitar, vocals), Barry Harvey (drums), Warren Morgan (keyboards, vocals) and Barry Sullivan (bass). That year they were classed as the top blues band in Australia.

“If Warren [Morgan] and Phil [Manning] went off on their 48 bars, I’d just join in at the end. All through my career I’ve been able to slot into that rhythm guitar playing area. I work with people who are incredible, talented. I’ve never had to worry about it much. I’ve been fortunate. Enough said.

“We did one album, Chain – Live. Then Chain split. So I just went, what am I going to do now? I went overseas. I had no responsibilities but they re-formed with Matt Taylor.”

When Glyn arrived in the UK there were a few people he could phone. He checked the current ads in NME and from them went to four or five rehearsals.

“In England trying out with various acts, I didn’t think a lot of the English acts were very good but the Australian acts and Kiwi talent of the time was way better in playing because everyone was working a lot. You die on your own swords in England. That’s exactly what happened to so many acts from here.

“I ended up in the backing band for this Ceylonese guy, Frankie Boy Reid.” Tony Cahill (second drummer with The Easybeats) was in the same band playing bass.

“Frankie was a mechanic by trade. He had a day gig. He had been a very successful musician, played in the northern England workingmen’s clubs. We did Eddie Cochran covers and rock and roll. I stayed as long as I could. He had a number of gigs. The band was quite good but it was never going anywhere. It was just a pub band.

“England was tough to live in [and] then the gigs started to drop off. As you can imagine in the world of the musician overseas if something folds, you’ve got to try to find work, any type of work. So I ended up lugging sacks of peas around at the big motor show at Earls Court in the catering department.”

This was a time of unrest in the UK. He knew it was time to go. After a very long trip back he ended up in working in Darwin. “The guys in Chain somehow found out I was back in the country. It was like the Blues Brothers – ‘Let’s get the band back together’ – so down I came to Melbourne.” The line-up he had been in the previous year reformed; this time he was in Chain from November 1971 to January 1972.

“We did a second album, Chain Live Again, and a couple of other singles. But typically all that time away they had had their most successful period with Matt Taylor.” (This was in the period they had huge hits like ‘Black And Blue’.)

Glyn had written songs such as ‘Passing You By’, ‘Rhubarb’ and ‘Little Fairy Michael’ with The Rebels, wrote ‘Mr President’ recorded by Chain and while he was with them co-wrote songs like ‘Pilgrimage’ and ‘Take Your Time’ with Phil Manning, Warren Morgan and the two Barrys.

In 1972 he joined Sydney band Copperwine, replacing Jeff St John. Following his time in that band, still in Sydney, he joined country-rock band Home. Trevor Wilson (ex-The La De Da’s) was in this band. Following its demise very early in 1975 Glyn joined Ariel, the band Mike Rudd (ex-Chants R&B) formed from the ashes of Spectrum.

Ariel had a huge live following. The band had already been to the UK and was going back on the second half of an EMI album deal. Glyn: “I joined the band, making it a five-piece. We went back but only lasted four months, EMI in their powerful wisdom hadn’t released the album. They did a budget reshuffle, cancelled about 20 acts of which we were one.

“John Peel, the successful London DJ, was a massive Aussie fan, he gave most Aussie acts that went there huge support and was super helpful.” Glyn knew he would have promoted this album for Ariel too.

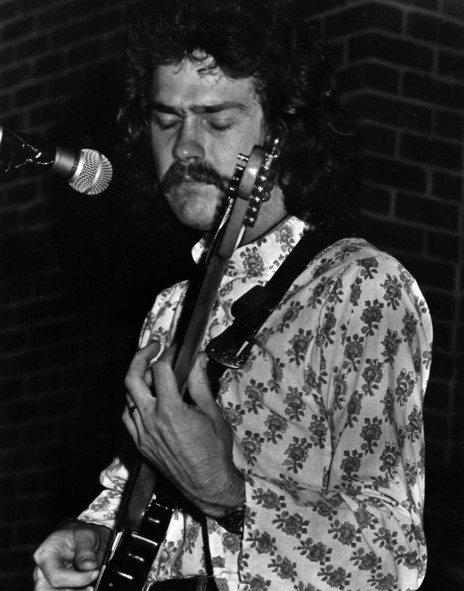

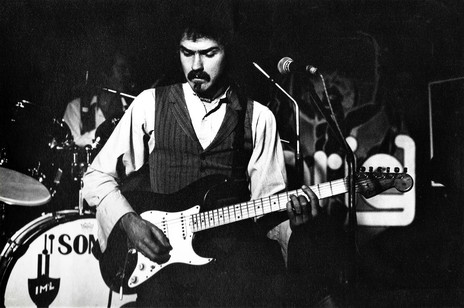

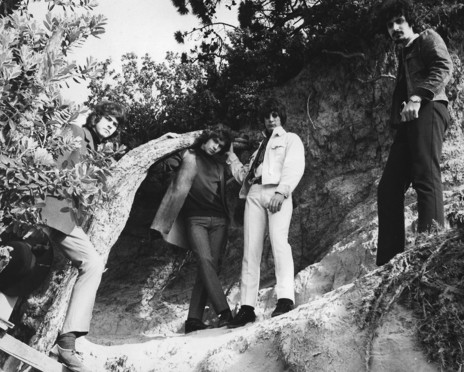

They returned to Australia. When Harvey James went to join Sherbet, Mike and Glyn shared the guitar duties. Bill Putt was still there on bass but when Tony Slavich (keyboards) joined their sound had evolved. In an interview for RAM at the time, Glyn observed, “The addition of keyboards has given us a wider base to work off.”

While Glyn was with Ariel they released the album Goodnight Fiona.

Reviewing an August 1976 gig in Juke, Stephen Charlesworth stated, “Glyn Mason’s guitar work shone up the whole night through and his lead breaks showed up capabilities that were previously overshadowed by the brilliance of Harvey James.”

While Glyn was with Ariel they released the album Goodnight Fiona. For a time Mike and Glyn were doing lots of songwriting individually. Together they wrote ‘Rock Critic’ and ‘Caught In The Middle Again’, while originals from Glyn sung by Ariel include ‘Redwing’, ‘It’s Only Love’ and ‘I’ll Not Fade Away’. In Ariel’s final line-up when Ian McLennan replaced Nigel Macara on drums, there were four songwriters in band.

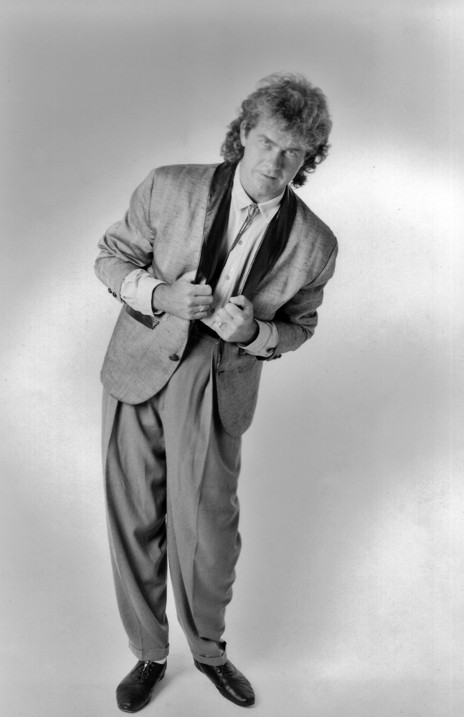

“Survival is a very powerful word in the music industry,” Glyn commented when speaking about the Ariel break up. He then embarked on some time as a solo performer. In those days in Australia a lot of the entertainment agencies were booking lesser-known acts to support high-profile bands such as Skyhooks.

“I was just hanging about with Frank Stivala from Premier having a rave one day and he said ‘Do you want to step on before so and so; do 35, 40 minutes?’ So that’s what I did for quite a while.”

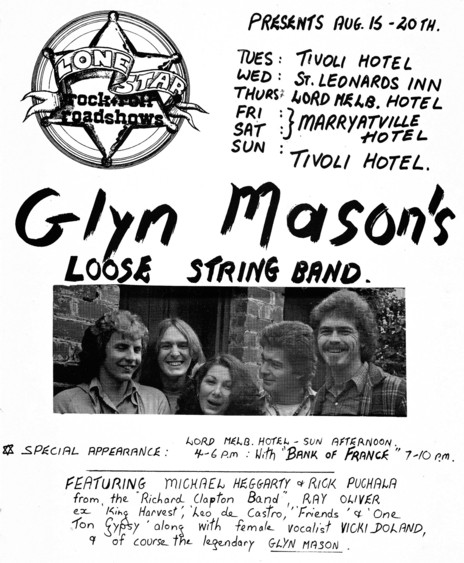

Around this time he also worked with the Richard Clapton Band. By 1978, he and the musicians around him came together as Glyn Mason’s Loose String Band. At the time he told rock writer Christie Eliezer that this group wasn’t a “band-trying-to-make-it” but one formed for live performance and recording.

“It gave me some momentum to really seriously take on writing some songs. It’s under my name so I’d better get into it. So that stood me in good stead. I thought we were a pretty good band.”

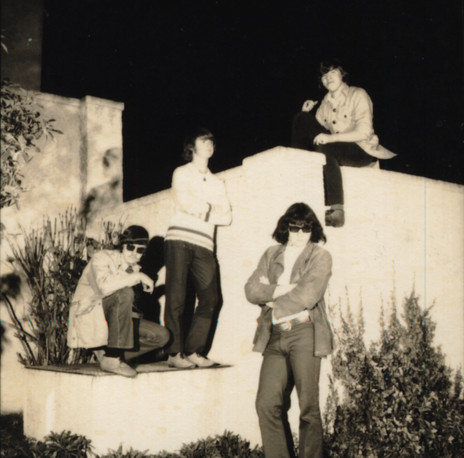

In 1978 Sam See and Chris Stockley had come back from overseas after the band they were in broke up, allowing Stockley, See and Mason to come into being. Chris had been in Cam-Pact (which had included Trevor Courtney after the Chants had folded); Axiom (with Glenn Shorrock and Brian Cadd); and the Dingoes. Sam had been in Sherbet, Flying Circus and Fraternity. The three of them were backed by drummer Dave Stewart (whose group Daniel had been produced by Mike Rudd), and Geoff Rosenberg (Hot Air Band) on bass.

The five-piece band played country rock. Early their emphasis was on country; later more on rock. They became extremely popular very quickly and by 1979 they were termed one of the hot acts for that year. They received lots of good press. Glyn recalled that the first 18 months in the life of the band was big.

One of the things they are best remembered for was Beg, Steal Or Borrow as a live album; a song and a 60-minute movie. These days the movie can be viewed on YouTube. It’s quirky, following the group from their beginnings to the release of their first album. It was produced by (former Fairport Convention member) Trevor Lucas and directed by Chris Lofven (who had previously directed Oz: A Rock & Roll Road Movie). Stockley, See and Mason were chosen for the film project (described as a “record on film”) because they were a new band.

Glyn described this pre-computer era. “Music was a big social thing. Everyone went out to listen to music and for a beer and it just happened that when they went out for a beer there were about six bands playing. You could go upstairs and see Skyhooks or Richard Clapton and downstairs there’d be cover bands or duos. That was how it was.”

In 1982 Glyn formed Tour de Force in Melbourne with drummer Dave Stewart (Stockley, See and Mason) and Joe Imbroll on bass. At the time they were described as “a collective of three musicians combining the best of their diverse backgrounds into a tight, unique R&B-based sound, coloured with a texture of today’s contemporary themes.”

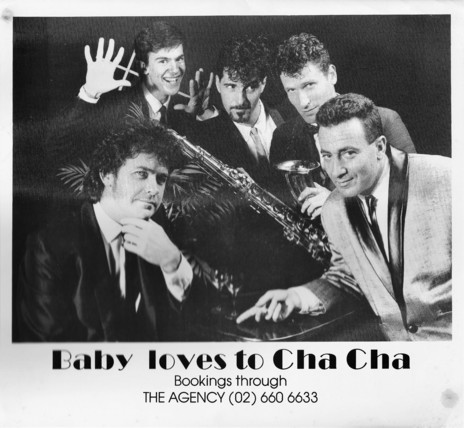

Sydney beckoned, so in 1984 Glyn based himself there to live and work. He was in a band named Baby Loves to Cha Cha doing soul covers and Motown songs. During his stint singing with them, he lost his voice for the second time in his career (the first time had been in Auckland). With Baby Loves to Cha Cha, Glyn really enjoyed singing so much soul music. “If your voice isn’t used to doing it, you’ve got to be careful,” he says. to recuperate took six months, which meant the band needed another singer until his return.

After leaving the band, Glyn took a break from music and started a landscaping business with a mate; at this time he was the fittest he had been in his life. But the city experienced its highest rainfall in something like 42 years, so his timing was unfortunate. He quit, selling his equipment to his business partner.

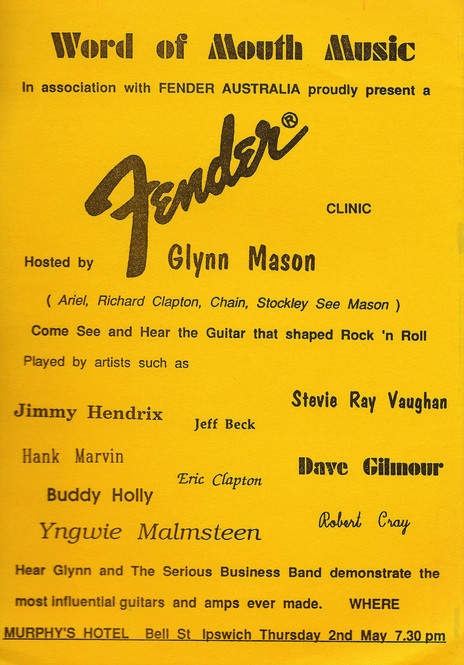

“I became an on-the-road rep for Fender musical instruments in 1989 and I lasted 21 years.” He knew the owners of some musical equipment shops; and he knew some of their customers or the guys they had in to teach guitar. “Most of these people I’d bump into either on that side of the counter or this side of the counter.

“It was a really good gig for an ex-muso; better than selling ball bearings or rubber tyres. I’m very thankful for that for all those years. I’d bump into these guys like Eddie Hansen from Ticket, or Lindsay Field. I knew him in New Zealand all those years ago. It was great.”

Glyn didn’t play any music for the first 16 years he was at Fender. But part of his territory was Melbourne and it drew him back. He did his first gig with Sam See in 2002, in Mordiallic at the food and wine festival. At that stage they were using their own names in the advertising and listing all the bands they’d each been in. “The people who came to watch us play, music enthusiasts, had seen the names on the poster.” People knew the bands they had been in but he joked about people not knowing their names. “When outfits we were in folded the people who were integral to the outfit like Mike Rudd with Ariel, or Phil Manning with Chain, those people were still known. ‘Can you name the other guys who were in Flying Circus or Ariel? We are those people!’”

“I came back to live in Melbourne in 2002 and worked with Fender part-time from about 2005. I retired from the sales gig in 2010. I wasn’t really a salesman but I knew about guitars. And I knew something about the people.”

These days Glyn often works with Sam See. In 2014 and 2015 they worked alongside Australian legends Brian Cadd and Glenn Shorrock in the hugely successful Sharky and the Caddman; a show performed at venues right across Australia. In 2017 Glyn and Sam are once again working with Brian Cadd and Glenn Shorrock in a new show scheduled for a limited Australian tour.

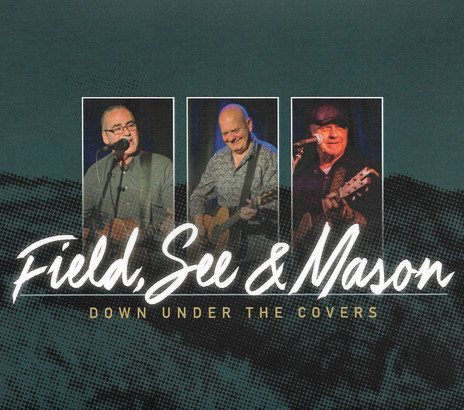

In 2014, they began working with Lindsay Field (ex-Original Sin) in Field, See and Mason, performing a mix of originals and covers. The three-part harmonies they deliver are stunning and the trio has released a CD, Down Under The Covers, which is an excellent representation of their live act. They work regularly at a number of different venues around Melbourne, including the Royal Oak in North Fitzroy.

“A huge percentage of our demographic wants to hear covers. We started doing 80 percent originals and 20 percent covers. They like hearing your original stuff.”

Glyn described the CD, recorded live in August 2016, as “classic Aussie covers twisted around our way, acoustic so nothing like the originals.” Sam did the arrangements. The CD sleeve gives more insights, noting that Sam suggested this project, which is “re-imagining Australian classics in Field, See and Mason mode. Fresh arrangements for three voices, three acoustic rock guitars, and stomp.”

Also during 2016, he played with Mike Rudd in two Spectrum-Ariel shows.

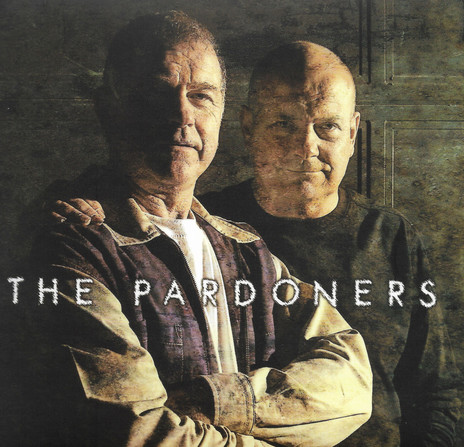

During 2016, Stockley, See and Mason performed a couple of times, including “a bit of a bash” mid-year at Melbourne’s Crackerjack Club. Mason and See have also performed as The Pardoners (the name that they began to use for the Glyn Mason-Sam See combination after they did their first recording together).

Glyn played with Mike Rudd in two Spectrum-Ariel shows during 2016, one at the Caravan Club, the other as support for Brian Cadd and the Bootleg Family Band in November. In gigs like these, when he sings his own songs solo, the audience is reacquainted with his magnificent voice.

Glyn wrote songs for both The Pardoners CDs: the self-titled CD released in 2006 and Indulgences in 2011. He is not doing as much songwriting at present because he is too busy. “The Pardoners got shelved a bit. I struggle with writing songs: always have. I’m the worst of the non-prolific writers I’ve ever met. I’ve written part of one new song in two years.

“We’re all reaching this ‘non-failsafe’ period. I’m glad I’m still standing and able to perform. I just want to play. I’m enjoying playing more than I ever did. The pressure’s off. I’m not trying to prove anything.”

During his brief stint as a landscape gardener in the 1980s – occasionally doing some session work – Glyn sang the ‘Adelaide Alive’ theme for a Formula One promotion. In an interview at the time he said, “I couldn’t imagine myself still singing for a living when I’m 60.”

Glyn Mason is over 60 now, and working a lot. “I love playing what I’m doing at the moment, probably more so than when I was younger.”

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air