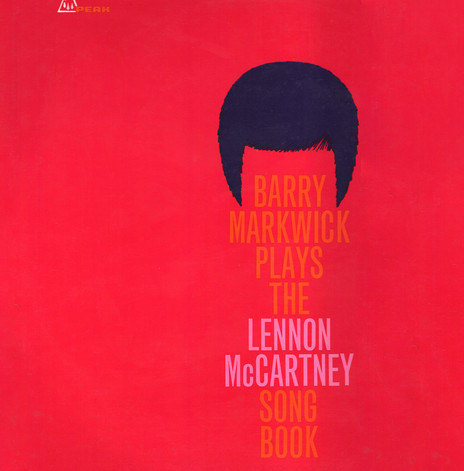

That said, the album Barry Markwick Plays The Lennon-McCartney Songbook – very hard to find these days – enjoyed modest success on Jack Urlwin’s Peak Records.

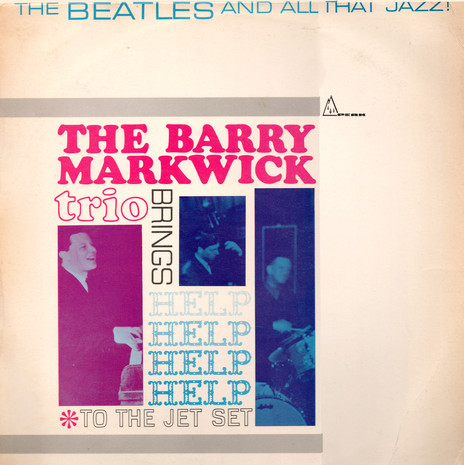

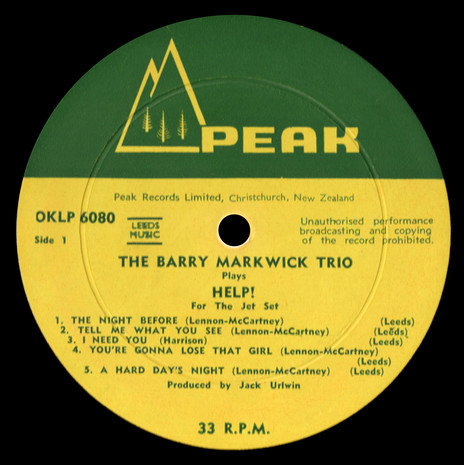

In May 1965, back from a business trip to the US, Urlwin told the Christchurch Press the album had been picked up for Europe and Britain by CBS and was under offer to a record company in New York. Although that may have just been talk. There was however a Markwick follow-up, Help! For the Jet Set, an album of Lennon-McCartney and Harrison tunes featured in the Beatles’ 1965 film Help!.

“Initially, my reaction to the Beatles was one of complete disinterest,” says Markwick.

Much as he wasn’t enamoured with the Beatles, Markwick admits, “The Beatle records were just a wonderful opportunity for me. I didn’t spend any time on the Beatles after that. They were news for quite a while so I aware of their antics but had reservations about their influence on music. Time has put them in the appropriate perspective; great enthusiasm for their compositions, little interest in their musicianship.”

The first Lennon-McCartney songs covered were by quick-off-the-mark British artists in 1963: an anonymous studio band, the Typhoons, knocked out a version of ‘Please Please Me’; Kenny Lynch covered ‘Misery’ (a song McCartney later said was “just a hacking job”) and Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas took ‘Do You Want to Know a Secret?’ to No.2 on the British charts.

Then dozens of pop groups around the globe – Ray Columbus and the Invaders here with ‘I Wanna Be Your Man’ among them – were picking up Lennon-McCartney originals.

Beatlemania broke globally in 1964 and by the end of the decade Beatles’ songs had been covered by pop and folk groups, heavier rock bands, populist outfits like the mainstream Boston Pops Orchestra, and Stax instrumental artists such as Booker T and the MGs with McLemore Avenue (their take on Abbey Road).

Jazz guitarist George Benson delivered The Other Side of Abbey Road in 1970. Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Ella Fitzgerald aside, jazz musicians were late to the Lennon-McCartney party, largely because their music had been sidelined by the global audience embracing exciting and increasingly inventive Beatle music.

“These four boys from Liverpool changed the musical face of the world in 12 months flat,” said Wellington jazz musician Ken Avery in his 1983 memoir Where Are the Camels.

Jazz clubs and musicians struggled, beat clubs opened. Pop and rock ruled.

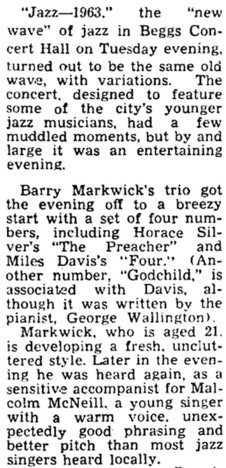

Barry Markwick, now in his 80s, grew up in Christchurch and was taught classical music. But from about 13 had his horizons broadened into jazz and standards; his teachers were pianist/drummer Harry Voice, and pianist John “Chuck” Fowler aka “Chook”.

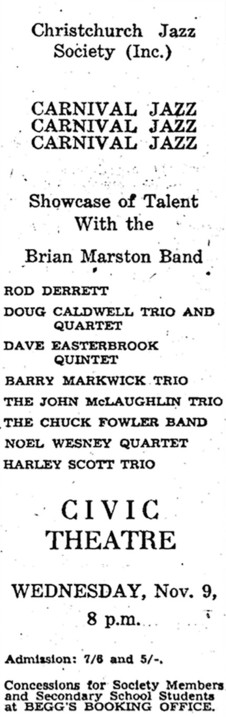

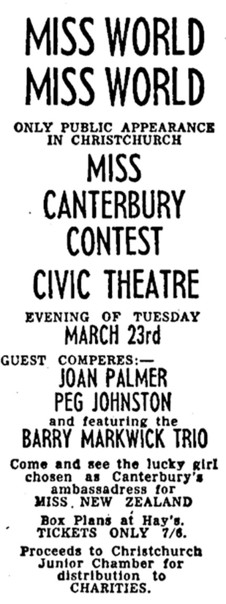

At the time the Christchurch jazz scene was vibrant around players such as saxophonist Stu Buchanan, pianist Doug Caldwell, the Brian Marston Band, Harry Voice and others. The Christchurch Jazz Society would meet in Begg’s Music Hall and arrange occasional concerts, but much of the work was for weddings, twenty-firsts and birthdays.

“Dances were still the primary form of weekend entertainment and the places you went to meet girls,” Markwick told Anna Dunbar of The Press in 2000. “There were also several cabaret-type clubs operating and offering live music. Although most of the music played had minimal jazz content, most of the musicians had some interest in jazz.”

On a return visit to Christchurch in 2008 he recalled his first jazz performance, at the Pink Elephant, with mild amusement. It was before an audience of largely disinterested Americans from Operation Deep Freeze, some of them smoking marijuana and “we could all enjoy the aroma”.

his debut was before an audience of largely disinterested Americans from Operation Deep Freeze

“Unfortunately, the servicemen were no better than today’s US audiences, more interested in talking than listening. Based on the quality of the performance, their disinterest at the Pink Elephant might have been well justified.”

Markwick, Voice, and Newson – the trio on the Beatles albums – played in various concerts and at university arts festivals. They had all been members of the Christchurch Jazz Workshop founded in 1963. “During the period [of lessons] with Harry, I used to visit his studios about an hour in advance and copy all the standards from the Great American Songbook I could find. I was also generating an interest in jazz at the same time, firstly via Frank Sinatra and then the big bands of Woody Herman, Count Basie and others.”

At that time however, contemporary jazz and many popular albums were hard to obtain but, as many did, Markwick sent money orders overseas to a mail order company in Britain. “They would ‘bank’ it for me. When I had accumulated several pounds, they would accept and ship an order. That’s how I heard jazz. And by listening and copying I gradually understood the medium.”

For Markwick in his late teens, 1959 was a seminal year with the release of Miles Davis’ Kind Of Blue, Charles Mingus’s Ah Um and the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s Time Out. In addition, there were “the wonderful Blue Note records that were being released”.

“Jack [Urlwin] and Peak Records had acquired the rights to Blue Note for New Zealand and as each shipment arrived I checked them out and purchased the ones that appealed to me. So I was given a good start to getting fine audio access to jazz. However, there were other albums that were successful and didn’t employ either original compositions, or 1920 to 1940 standards. For example, the drummer Shelly Manne’s [1956] album My Fair Lady with pianist Andre Previn proved that other material could be turned into acceptable jazz performances. I think these type of albums stimulated me to think of alternative material.”

Enter Lennon-McCartney, at the suggestion of the entrepreneur and businessman Urlwin.

“I’d become friendly with Jack following an introduction by a master at Christchurch Boy’s High School, [jazz singer/ex-All Black] Pat Vincent, and subsequently was invited to Jack’s frequent house parties, becoming the go-to pianist for a trio featuring Jack on drums and Harry (Hoot) Gibson on bass. The material we performed was always standards. These visits turned to the possibility of producing an album. Jack’s children were enamoured with the Beatles and the suggestion was made to record some of their tunes.”

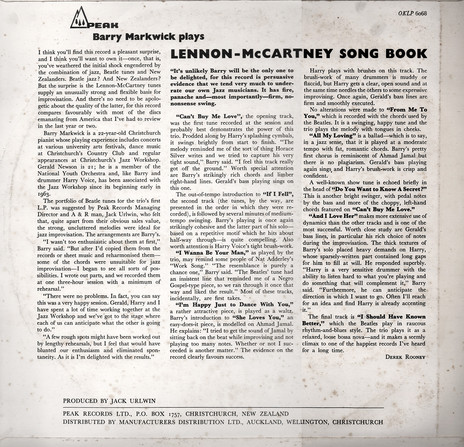

For an album recorded hastily – all the songs arranged by Markwick – Barry Markwick Plays The Lennon-McCartney Songbook is an enjoyable and impressive debut by the young pianist.

Peak label owner Jack Urlwin’s children were enamoured with the Beatles

‘Can’t Buy Me Love’ has the cool swing of the Ramsey Lewis Trio (then enjoying the hit ‘The “In” Crowd’), he flies through the ballad ‘If I Fell’ after a faithful start, finds something worth exploring in the barely interesting ‘I Wanna Be Your Man’ and turns ‘I’m Happy Just to Dance With You’ into a jazz waltz.

On the back cover Markwick acknowledges he tried “to get the sound of [Ahmad] Jamal by sitting back on the beat while improvising and not playing too many notes” on ‘She Loves You’.

If ‘And I Love Her’ is too close to the piano bar then the bossa treatment of ‘I Should Have Known Better’ which closes the album is a bit of fun.

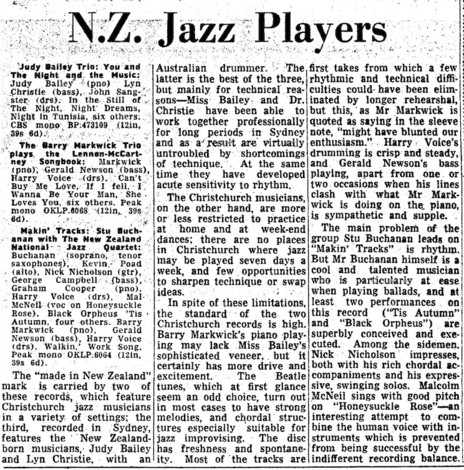

The album was reviewed in the Christchurch Press in May 1965 alongside albums by the Judy Bailey Trio and Stu Buchanan with the New Zealand National Jazz Quartet. Both albums featuring Markwick, including the Buchanan album on the Peak label, are also with Newson and Voice. That was an indication of just how productive the local scene was at the time.

“The Beatle tunes, which at first glance seem an odd choice,” the reviewer writes with some surprise, “turn out in most cases to have strong melodies, and chordal structures especially suitable for jazz improvising.

“The disc has freshness and spontaneity. Most of the tracks are first takes from which a few rhythmic and technical difficulties could have been eliminated by longer rehearsal but this, as Mr Markwick is quoted as saying in the sleeve note, ‘might have blunted our enthusiasm.’

“Harry Voice’s drumming is crisp and steady and Gerald Newson’s bass playing, apart from one or two occasions when his line [clashes] with what Mr Markwick is doing on the piano, is sympathetic and supple.”

In a cover reflecting its period – the Beatle hairstyle enough of a symbol of the era – Barry Markwick Plays The Lennon-McCartney Songbook rose without much of a trace.

However, “while it didn’t make the Down Beat [American jazz magazine] five-stars list, it made enough money to justify a second,” says Markwick. “I’m sure Jack wasn’t able to fund his retirement with the proceeds from both albums, but there was a follow up soon after the initial album.”

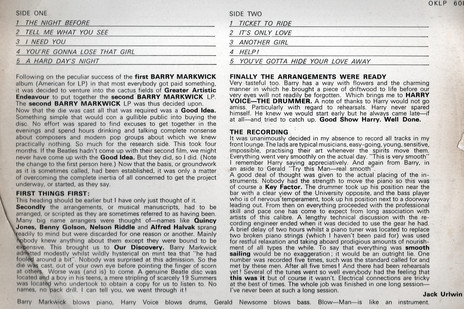

That second album of Help! tunes is more perfunctory than the trio’s debut, some of the casual nature captured in Urlwin’s frivolous and amusing liner notes. He opens with: “following on the peculiar success of the first Barry Markwick album (American for LP) in that most everybody got paid something, it was decided to venture into the cactus fields of Greater Artistic Endeavour to put together the second Barry Markwick LP.”

“The second Markwick LP was thus decided upon. Now that the die was cast all that was required was a Good Idea.

“THE BEATLE TUNES,” WROTE THE PRESS REVIEWER, “TURN OUT IN MOST CASES TO HAVE STRONG MELODIES”

“Something simple that would con a gullible public into buying the disc. No effort was spared to find excuses to get together in the evenings and spend hours drinking and talking complete nonsense about composers and modern pop groups about which we knew practically nothing.

“So much for the research side. This took four months. If the Beatles hadn’t come up with their second film, we might never have come up with the Good Idea. But they did, so I did. (Note the change to the first person here.)

“Now that the basis, or groundwork as it is sometimes called, had been established, it was only a matter of overcoming the complete inertia of all concerned to get the project underway, or started, as they say.”

Urlwin continues in this casually down-playing manner noting “to say that everything was smooth sailing would be no exaggeration; it would be an outright lie.”

The 10-song album was recorded in a single session. “I was always fairly pleased with the results,” says Markwick, with one caveat: “The piano was unfortunately out of tune – the recording was made in Jack’s living room by Keith Robbins – so it did suffer from a lack of a good sound studio.”

But with two albums behind him, Barry Markwick largely walked away from music. “I recognised fairly early I would never be good enough to become a musician on a par with those I held in the highest esteem, and as I was reasonably good at maths at school, a job in accounting seemed to be a logical extension.

“After the mandatory five years in an accounting office and time at University, I finished up with a CPA [Certified Public Accountant] designation. I guess music was always a hobby – a passion, but nevertheless still a hobby.”

And he was never tempted to record again?

“No. I moved on to visit the US so became engrossed in the opportunities to see ‘live’ jazz musicians who had been my idols. I left New Zealand in February 1966, at age 24, on the liner Canberra and two weeks later landed in San Francisco. I had purchased a $99/99-day ticket on Greyhound bus lines.

“My one case got heavier and heavier as I travelled throughout the US buying records at almost every stop. I couldn’t believe the availability and the price. My music experiences had been a wonderful slice of life for me, but evolved to be less significant. My priorities became my family and work aspirations.”

MARKWICK: JAZZ IS A VERY DEMANDING MUSIC, WITH MINIMAL FINANCIAL RETURNS FOR LOADS OF EFFORT

Markwick has occasionally returned to Christchurch and is remembered for being part of an important scene in the late 50/early 60s. He remains outside the music but is an observer.

“Jazz is a very demanding music, generating minimal financial returns and loads of effort and commitment. Jazz musicians tend to be dismissive of pop music because generally it does not require significant sacrifices (in their mind), it is relatively simple in construction and – for the successful few -- provides an enormous return.

“In a nutshell, [jazz musicians feel] a sense of frustration in not getting acknowledgement for their efforts. As I look back on the direction of popular music, I think the emphasis placed on the use of the guitar as the primary instrument has been the main contributor to its downwards direction. Augmented by an emphasis on extreme volumes, the pop music industry finds itself in the dismal musical state it is today.

“For my own part, the road had not been difficult, acceptance fairly easy and I was in a very accommodating family. These factors enabled me to do whatever I wanted, be it cricket, soccer, music, even riding my bike to a night club to perform!”

But did he realise that he was among the first, perhaps even the first, jazz musician to record a whole album of Lennon-McCartney tunes?

“I hadn’t thought of the project in those terms. Makes me feel quite honoured.”