She has recalled moments that were like epiphanies that led to her life in music. “I didn’t really have any choice in the matter,” she told New Zealand composer Gillian Whitehead in 1991. “It was just one of those things that seemed to have a mind of its own.”

During her Whangārei childhood, she heard classical and pop music from her family’s valve radio in the kitchen. While still very young, she witnessed a friend of her parents, Norm Cox, performing swing piano at parties, “a lovely swinging-type party piano which I thought sounded very jolly and nice, and very attractive.” Her parents remembered her trying to pick out the melodies on the piano.

Although her father played violin, live music only really entered the house when she was aged 10. A piano arrived, and she started lessons in classical piano and theory at a local convent, with a nun called Sister Rita being especially influential.

When Bailey was 13, a school friend called Mary Main played her a disc by Fats Waller, which brought back memories of her early love of swing. In the same year, she heard the standard ‘East of the Sun’ on the kitchen radio. Played by the George Shearing Quintet, it was her introduction to improvisation, and once again Bailey was inspired to go to the piano and work out what was happening. Within a week she heard the Stan Kenton Orchestra, which, John Shand wrote in 2020, “gave her an even bigger thrill, the thought of which still gave her tingles decades later.”

Bailey was underway, exploring outside her classical training. In her extensive interview with Whitehead – who also grew up in Whangārei – she said, “I gradually picked up on other music – popular melodies of the day, playing those by ear, putting my own chords to the tunes, devising basses to them, inventing my own left-hand figures – I did it purely by instinct, and it sort of snowballed right up to the point where finally, after getting my ATCL when I’d just turned 16, I left classical studies alone for a while.”

Two years later, while studying for her LTCL, her Auckland teacher Oliver Harris could see that her focus had shifted from classical music, and encouraged her to work on her own musical interests. “By this time of course the dreaded jazz had really taken hold of me,” she told Whitehead.

The improvisation was the main appeal, at a time when it “was finally coming into its own almost as a separate art form.”

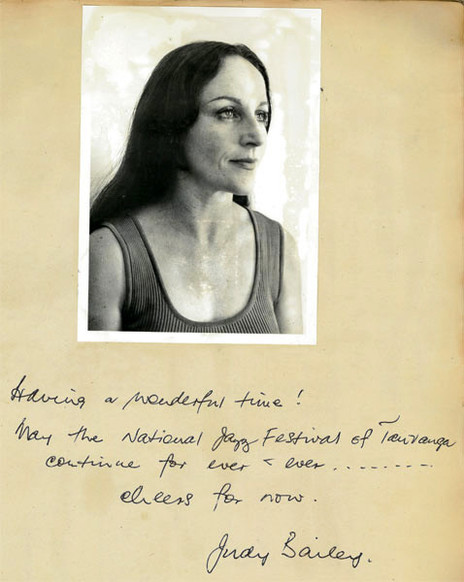

In Auckland in the late 1950s, Bailey began playing in clubs and restaurants

In Auckland in the late 50s, while working at a bank, Bailey began playing in small combos in clubs, or solo in venues such as the Hi Diddle Griddle restaurant. She was given the opportunity of writing and arranging for the NZBC radio band in Auckland, a coup for someone so young. “The pieces were successful and were used on the air, so that led me to try, rather tremblingly, my first big band arrangement, and again that was successful,” she told Whitehead. “The notes seemed to be in the right place and the sound seemed to be what it was supposed to be, and so they also used that for broadcast.”

While working with the radio band, she met trumpeter Neville Blanchett, who became her husband. Together they travelled to Australia in late 1960, intending to stay for six months before heading on to London. But opportunities in the Sydney jazz scene opened up immediately for Bailey, and she has been based there ever since.

In Sydney she was hired by Tommy Tycho to play with his Channel 7 Orchestra – on the recommendation of Julian Lee. As well as sessions and gigs, she remained working in TV music for eight years, on other channels and in other bands, including those of Don Burrows, John Bamford, and Jack Grimsley.

The city’s hippest jazz venue in the early 60s was the El Rocco, a downstairs club in Kings Cross on the corner of Brougham and William Streets. Originally the attraction for the guests was a television set, but the club began recruiting jazz musicians to play after transmission closed at 10pm. Australian jazz historian John Clare wrote the El Rocco “struck exactly the right tone for a Kings Cross coffee-shop. The Cross was in those days a very liveable environment in which an underworld … rubbed shoulders with an artistic and intellectual bohemia.”

Bassist Bruce Cale compared the Cross scene then to what was going on in New York’s Greenwich Village. “There was the gangster element, but there was a lovely feeling of going to the Cross, to coffee lounges, and talking about music until four in the morning.” Musical mainstays at El Rocco were hard bop and cool jazz – the two camps competed – plus there was an encouragement to experiment outside these styles. The club was also known for its nurturing of emerging players.

US saxophonist Bob Gillett performed at El Rocco in 1958 on his way to New Zealand and, as well as Bailey, expats from Aotearoa included Mike Nock, Dave MacRae, drummer Barry Woods, and bassists Andy Brown and Lyn Christie. Also playing with Bailey at the club were Stewie Speer (later with Max Merritt), Irish bassist Rick Laird (briefly a New Zealand resident, and later with the Mahavishnu Orchestra), Don Burrows, Graeme Lyall, and John Sangster.

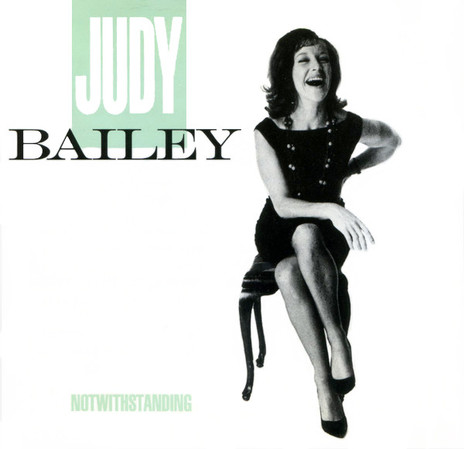

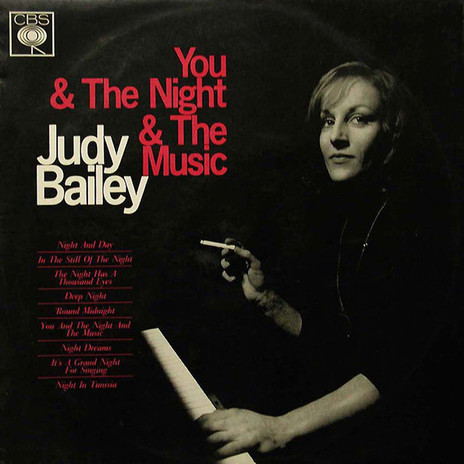

Bailey first appeared on disc as part of the Errol Buddle Quartet, arranging and recording their 1962 album The Wind (HMV). Her debut LP as a headliner was with Christie and Sangster as her rhythm section. Comprising standards with “night” in the title – among them, ‘Night and Day’ and ‘Night in Tunisia’ – You & The Night & The Music came out on CBS Australia in 1964.

Bailey’s debut album was described as “the swingin’est to have been produced in Australia”

The liner notes describe You & The Night & The Music as “the swingin’est album to have been produced in Australia.” Over 50 years later, John Shand concurred, writing that the album “sizzles with the energy of youth and adventure, while also being sensuous, playful, heartfelt, effortless and lithe. Bailey turns in a solo ‘’Round Midnight’ that’s as desolate as any you’ll hear, and her own ‘Deep Night’ signalled the start of an august parallel career as a composer.”

My Favourite Things followed in 1965: jazz standards, with Sangster again on drums, Ed Gaston on bass, and an expanded combo featuring Graeme Lyall on tenor, and Jack Grimsley on trombone.

Bailey briefly returned to Auckland in March 1970 for her first gigs since departing a decade earlier. Now married to US jazz bassist Richard De Gray, and with the first of her two children in tow, Bailey played the Soul of Jazz event at the Peter Pan Cabaret, as part of the Auckland Festival. Backed by the Neophonic Band (led by Bernie Allen), Bailey’s repertoire was mostly her own originals, which she also arranged. She played other gigs with a trio: De Gray on bass and Frank Gibson Jr on drums. “With the baby [daughter Lisette] to care for,” Bailey told the NZ Herald, “I have little chance for playing, so I have been concentrating on composition and arranging.”

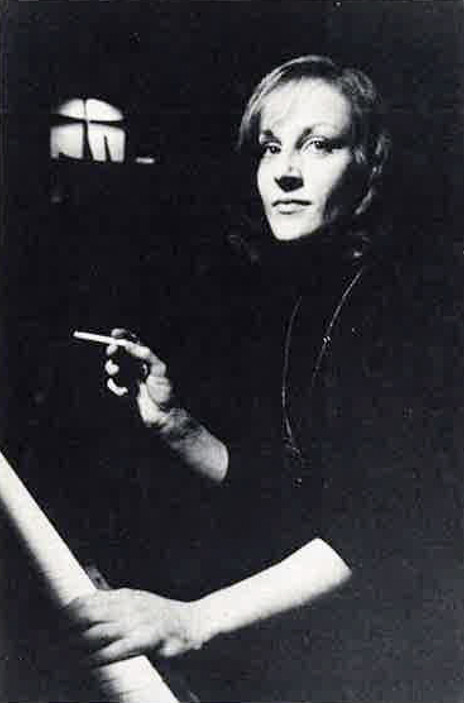

From 1973 Bailey was a founding teacher in the jazz studies programme at the NSW State Conservatorium, where she remained on staff into the 2010s. She also became the pianist on the ABC children’s radio show Kindergarten.

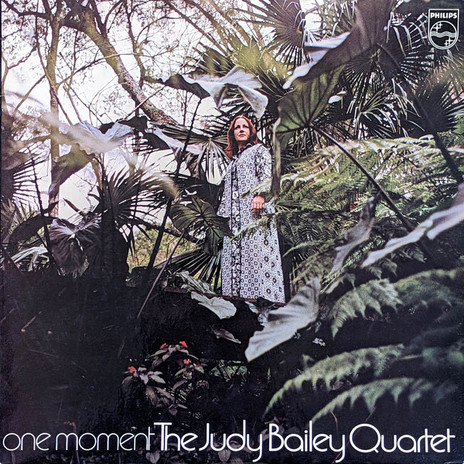

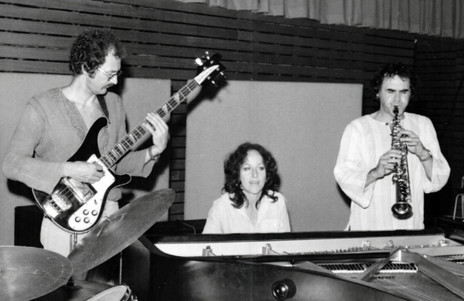

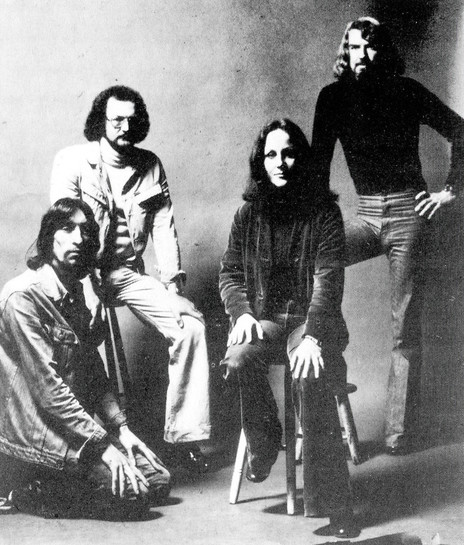

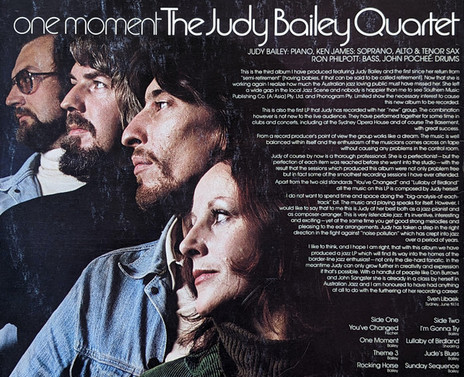

The following year she formed a quartet with Australian players that would be her main jazz vehicle for the next decade: saxophonist Ken James (later replaced by Col Loughnan), bassist Ron Philpott, and drummer John Pochée. An album from the quartet, One Moment, came out on Philips in 1974. The combo toured Asia for Musica Viva in 1978, and with Philpott she represented Australia at the Singapore Fesival in 1983. Another Asia tour took place in 1986.

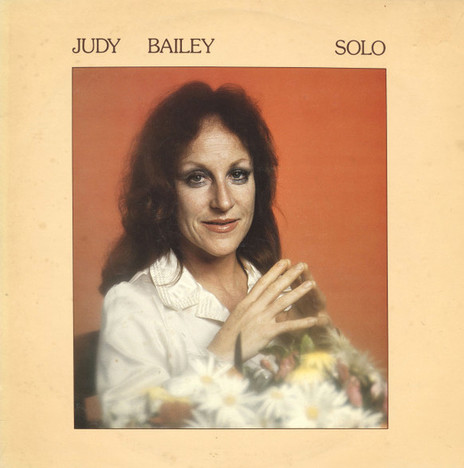

Bailey first solo album – Solo – came out on Eureka in 1978. Recording on the afternoon of 15 October 1977 in the Sydney Opera House recording hall, one side featured her own compositions (including ‘Jude’s Boogie’ and ‘Jude’s Cakewalk’), the other her much-acclaimed ‘The Spritely Ones’, and a Beatles medley.

In this period she mixed teaching, music administration, and performing; she was appointed musical director for jazz performances and lectures at the Sydney Opera House, and became a member of the Music Board of the Australia Council from 1982-86. She was the first recipient of an APRA award for jazz composition in 1985.

Bailey’s prowess at composition and orchestration has seen her write for small jazz ensembles, big bands, and also large orchestras. In the 1990s she increasingly wrote works that integrated jazz and classical; among the results were Two Minds, One Music (for symphony orchestra and jazz big band), Australiana Suite (for jazz big band), Out of the Wilderness (for symphony orchestra and jazz soloist, James Morrison).

In 1996 Bailey made a rare return visit to Aotearoa, performing solo in Wellington

In 1996 Bailey made a rare return visit to Aotearoa, performing in the concert chamber of the Wellington Town Hall. Reviewing the solo performance for the Evening Post, pianist Gilbert Haisman wrote, “Judy Bailey has a wonderful harmonic sense, a great gift for interpretation, and a compelling dramatic instinct. There were many moments when these strengths so transfixed the audience that even the most insensitive pin would not have dared to drop ... A considerable part of Bailey’s talent is dramatic; her dynamics can be exquisite and utterly seductive.”

As the 1990s came to an end she began to turn towards Aotearoa in her compositions. According to Sounz, while working on Gillian Whitehead’s Ipu in 1998, with Richard Nunns and Steve Garden she “conceived a project that would explore the sonic and musical interplay between piano and taonga pūoro”. This led to the album Tuhonohono (Rattle, 2000), which began from “improvisations loosely based on thematic springboards such as ‘birth’, ‘childhood’, and play’.” Sounz writes that on Tuhonohono, “The ancient sounds of taonga pūoro and piano combine to create music that is reflective, playful, and mysterious” (an extensive list of Bailey’s works can be found on the Sounz website).

In a fascinating 2009 interview with Bailey, Australian record producer Belinda Webster described her as “an icon of Australian jazz. For more years than she would care to admit Judy’s been giving pleasure to Australian jazz enthusiasts, from the days of El Rocco right through to the present. Until the last two decades she has been the only woman in the top echelons (but won’t talk about gender in music) and has forged her own way through her career (without any female mentors). She has spent years writing magnificent music that seems, so far, to have been avoided like the plague by our symphony orchestras.”

Trying to break down the barriers between jazz and classical music has been a longtime goal

Trying to break down the barriers between jazz and classical music has been a longtime goal for Bailey; it “fulfils a need inside me,” she told Webster. “Wanting to – symbolically, through music – indicate to as many people as possible that it is possible, and in fact highly desirable, to bring about harmony between previously conflicting parties or entities. I’m talking about a perception which I think has existed for a long time, that there is a line of demarcation between classical music and jazz.

“That is representative of all other lines of demarcation – between this religion and that religion, or this country and that country, or black and white people. There are so many frightening, immensely sad instances of conflicting entities and, for me, the business of trying to bring together two possibly conflicting entities in music is a way to symbolically indicate, ‘Hey, it can be done. They can come together and exist happily.’ ”

A surprising turn came in 2017 when Bailey was asked permission by US rapper Rick Ross to sampled a clip from ‘Colour of My Dreams’ from the Judy Bailey Quartet album Colours, released 40 years earlier. The sample was used on Ross’s track ‘Santorini Greece’ on the album Rather You Than Me.

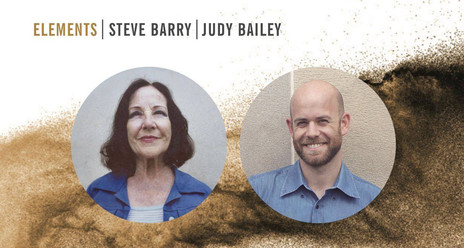

In 2020, Rattle released Elements, a collaboration between Bailey and expatriate New Zealand pianist Steve Barry, whom she had taught at the Sydney Con. Performed on two pianos, their exchanges on this live album of free improvisations were described by John Shand as “organic verbal conversations between erudite friends.”

While mostly remembered in New Zealand by jazz aficionados, the respect Judy Bailey enjoys in Australia is shown by her many awards – among them an Order of Australia medal in 2004 – and the continued affection of her listeners, former pupils, and peers.

--

Read more: Judy Bailey: an improvised career, by Eric Myers, 1986

Read more: Judy Bailey's recorded music, by John Shand, 1986

--

Sources (more are in Links, below)

Judy Bailey & Gillian Whitehead: a conversation, Music in New Zealand, Summer 1991-92

John Clare, Bodgie Dada & the Cult of Cool, UNSW Press, 1995

John Shand, “How Judy Bailey's six-month stay became 60 years,” Sydney Morning Herald, 31 August 2020