The New Zealand recording industry was just beginning, and after HMV’s pressing of US singer Dinah Shore’s ‘Buttons and Bows’ in 1948, the Radio Corporation of New Zealand followed quickly with the now-perennial request-session favourite: Tanza’s 78rpm pressing of Ruru Karaitiana’s ‘Blue Smoke’ sung by Pixie Williams.

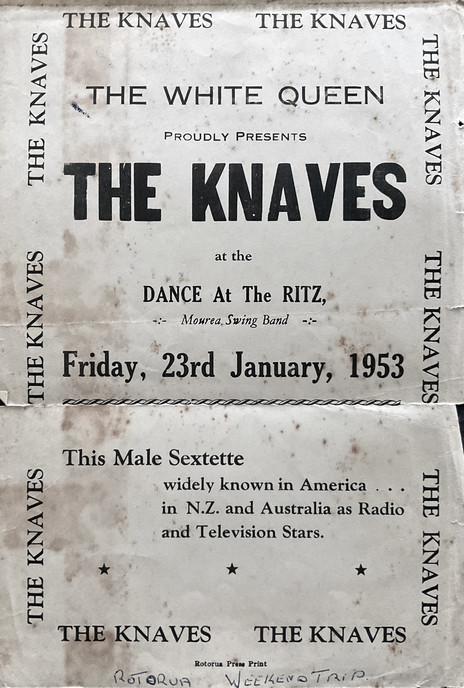

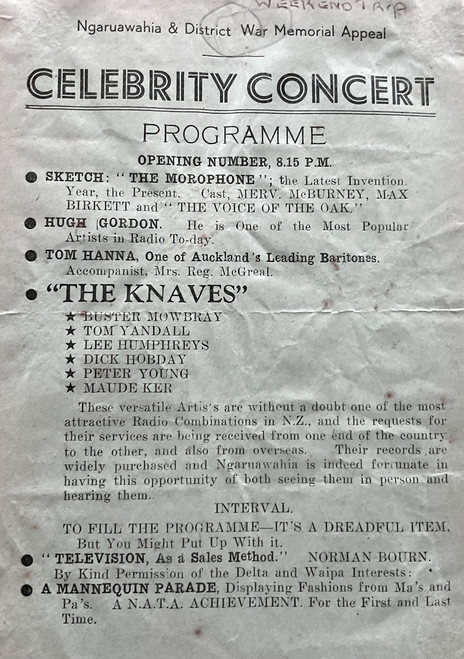

The Knaves swiftly became favourites on the air. Rather than being musical elitists or specialists, their variety of styles and slick presentation won them popular appeal. With their slippery, exacting harmonies, precision backings, and crazy sound effects in the wacky, often frenetic style of gum-chewing bandleader Spike Jones, they were unrivalled radio stars. They toured New Zealand for the NZBS, had a regular 15-minute slot on the YA network, and were kept busy with requests for live appearances in various cities.

Although players at Tanza or Stebbing’s recording studios in the 1950s and 60s were mostly jazz musicians (and “canaries” – female singers – were predominant out front with bands), the populace was still largely suspicious then of jazz, according to pianist Crombie Murdoch, a mainstay of the New Zealand jazz scene. In a 1967 interview he said, “Most people hated jazz. Only musicians and a few members of the public liked it. To others it was wicked, criminal, decadent.”

Reporter Andrew Fraser attended The Knaves’ final 1YA recording session with wisecracking scriptwriter and compere Wally Ransom. He wrote: “From behind the partly closed sound-proof studios came sounds of wild revelry, laughter, drums crashing, cowbells, bullets ricochetting [sic], and voices in close harmony.

“It could have been a whoopee party somewhere in Korea. Or a cart-load of monkeys in a tin-can factory. Or maybe the fightin’, feudin’, mountain boys at full throttle. Or just a scandalized Mrs Murphy bewailing the overalls in the chowder.”

So, who were those stylish gents The Knaves, with their knowing grins, spivvy suits, bow-ties and pencil moustaches? With a wink and a nod to their musical forbears, from Noël Coward, vaudeville, and barbershop to contemporary vocalisers the Ink Spots, they gave themselves the perfect name to sum up their form, their history, their repertoire.

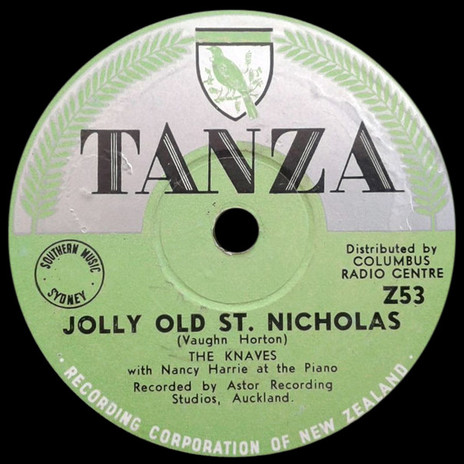

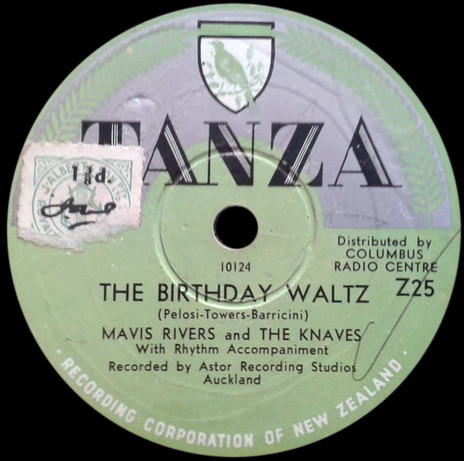

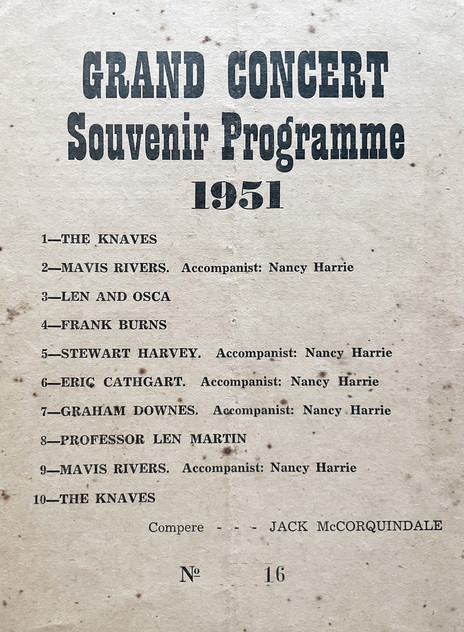

Their first line-up featured Phil Maguire, Lee Humphreys, Claude Ker, Clive Arndt, and Doug “Buster” Mowbray on piano and ukulele. The idea for the group had been mooted by Lee Humphreys and his wife, pianist Nancy Harrie, during a Quintones rehearsal. Thomson Yandall came in on double bass after Arndt retired, and others joining later included Peter Young (a former 1YA announcer), guitarist Dick Hobday and Bob Ewing, who replaced Yandall on bass.

“It could have been a whoopee party somewhere in Korea. Or a cart-load of monkeys in a tin-can factory ...”

The initial five-piece put down their 78rpm mono debut, with backing from Wally Ransom’s Rhumba Band in Auckland at Noel Peach’s Astor Studios on Shortland Street in 1949. This was released on HMV, the major label’s second disc by New Zealand artists.

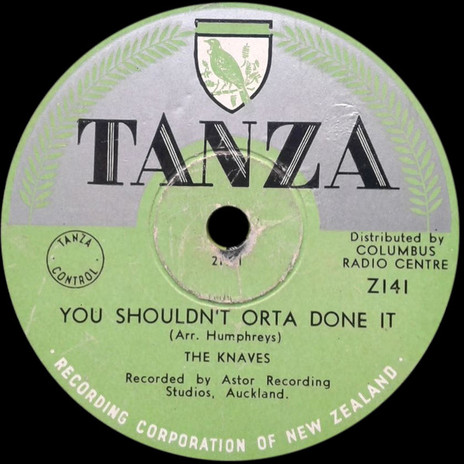

The song was ‘He Holds the Lantern (While His Mother Chops the Wood)’ backed with ‘Powder Your Face With Sunshine’. It set the tone for the often novelty comedic and old-time offerings that followed, with sound effects and instrumental surprises, such as ‘We Got to Put Shoes on Willie’, the Irish-styled ‘Who Threw the Overalls (in Mrs Murphy's Chowder)’, ‘You Shouldn’t Orta Done It’ and old favourite ‘Sweet Violets’. The twittersphere took on its own meaning for them when they stopped using instruments and objects such as empty beer bottles, boxes of nails and hammers to create birdsong or gunshots or train whistles and instead just vocalised them.

An admiring reviewer of the day rated their recordings and “lilting style” superior to American offerings. “This is definitely not for high-brows, but most middle brows could listen without squirming.”

They often costumed up for an appearance. A diary kept by Claude Ker’s wife Violet aka Vicky notes their Western Springs Carnival attire: arriving in a Daimler, they stepped out with long black beards, braces, ragged trousers and bare feet or hobnail boots, with one carrying a flagon of beer.

The group burned bright for a brief handful of years and then pfft!, they were gone. By 1953 the members decided to go their separate ways. They were starting families or businesses and needed regular money. This was much to the disbelief of such institutions as Australia’s music magazine, Music Maker, which described the decision as a “bombshell”.

Possibly they saw the writing on the wall, with The Knaves’ style looking more backwards musically than forwards; also, the population was too small to support fringe styles as theirs would have been if they had kept going. Topping the charts in places like Pakistan (noted in a 1953 Listener article) was not going to cut it for a solid future.

Before The Knaves, bandleader Lee Humphreys played with the Wally Ransom Rhumba Band. His Mercy Convent-trained, Greymouth-educated jazz pianist wife, Nancy Harrie, was in demand as a studio session and broadcasting accompanist for top vocalists such as Mavis Rivers, and the first television studio pianist during an experimental broadcast in 1951. Together, the pair continued to collaborate on record and radio after The Knaves broke up.

Humphreys recorded versions of ‘Goodnight Irene’ and ‘On Top of Old Smokey’, recorded with the Sundowners, then died prematurely in 1959. Doug Mowbray went on to have a long solo career, singing with his ukulele or working as piano accompanist for various artists.

Under his Buster Keene pseudonym, Mowbray released around 40 sides on Tanza in a mix of styles, from novelty pieces and cowboy country to standards and spirituals. He duetted with Dorothy Brannigan on some 20 Astor Studios-recorded Tanza releases and recorded with other musicians and various line-ups, including Crombie Murdoch and His Rhythm, the Lloyd Sly Quartette, and various groupings echoing the recording location at Astor Studios: the Astorians, the Astor Rhythm Boys, and the Astor Trio. He also continued to enjoy barbershop with the Three Lads, his post-Knaves group, until his death in 2003.

Clive Arndt retired, Phil Maguire moved on to commercial radio in Australia and in-demand double bass player Thomson Yandall popped up in various line-ups around Auckland. Like many other up-and-coming jazz players, he had cut his teeth in the band at Auckland’s Crystal Palace under the leadership of dynamic bandleader Epi Shalfoon alongside other long-time New Zealand-jazz luminaries, such as Frank Gibson, Julian Lee, Jim Warren, Tommy Kahi, George Campbell, and countless others.

In 1943 Yandall played with the resident band at the Trocadero on Auckland’s Queen Street with popular young wartime (and beyond) vocalist Pat McMinn and at the Auckland Swing Club with pianist Crombie Murdoch and drummer Neil Dunningham, with Julian Lee on solo sax.

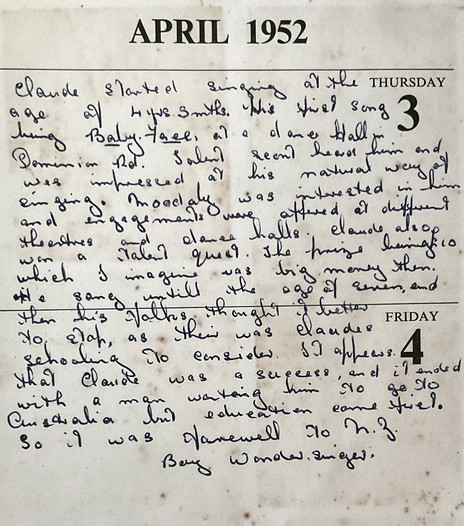

Vocalist Claude Ker opted for civvy street in order to support his family. While he was with The Knaves, his wife, Violet “Vicky” née Sumic, kept a diary of their performances, saving their press clippings and promotional material, and adding them to the diary with her written remarks. It makes for intriguing reading.

Claude Ker made his first stage appearance aged 4, singing ‘Baby Face’ at a Dominion Road theatre.

Born and raised in Auckland, Claude Ker had already had extensive work experience in song and dance long before he joined The Knaves. His piano-tuner father taught him to play and he made his first stage appearance aged just four years, three months old at the Burlington Dancing Club in Dominion Road, singing ‘Baby Face’. Talent scouts heard about him and soon he was appearing all over Auckland.

Heralded as “Auckland’s Little Wonder”, “N.Z.’s Own Jackie Coogan” and the “Sensational Boy Wonder” who “Created a Riot at his Last Appearance”, he played piano and sang, often appearing in blackface. His parents allowed him to continue until he was seven and, despite invitations to appear in Australia, they decided that enough was enough, and that school was more important than the stage.

The “Boy Wonder” never lost the urge for music and performance. As a young man on the troop ship heading to war in the theatre of Egypt, he entertained the troops by playing piano out on the deck. Shellshocked by an enemy attack that left him the only survivor among his group of friends on patrol, he was sent to Rome to recuperate. There he worked in the supplies at the hospital, making pocket money on the side with a black-market line in manchester.

After his war experience The Knaves must have been a welcome bridge back into music and society. There was tight camaraderie among the group and their music and on-stage hilarity was a release. They remained close friends after the group disbanded.

Claude’s Brisbane-based son, Gary Ker, shared some memories. “Home was Dominion Road in Mt Roskill and we lived there until Mum and Dad split up when I was about 13 or 14 (about 1964).

“We grew up with Lee Humphreys, Nancy Harrie and all those people. In the 50s and into the 60s when everyone else had a party at home they’d put a radio on or play a record. We used to have people sitting out the front of our house on chairs, listening to the music, because it was brass, tea-chest bass, upright grand, snare drum and guitar – we grew up with music. Dad’s mates all played.”

Gary and his three siblings all learned piano, and he guitar, although none played professionally. Their younger brother died in his 20s. Claude and Vicky separated before 1968, with Vicky and the other three moving to Australia. Claude remained in Auckland and for him the music never stopped.

“Dad had his own plastering business, but he still went around and played. As long as he could get his wretched piano to a pub he played. He did that for donkey’s years. He just loved playing. I never even knew he sang until I started reading into it.”

Claude Ker died in 2008 aged 85 at the Ranfurly Home in Mt Albert for old soldiers.

Of The Knaves’ demise, reporter Andrew Fraser, wrote, “At times radio fans have mistaken them for a crack overseas combination, for their broadcasts have always been slick, fast-moving and delightful from the moment they arrive on stage with a scream of tortured machinery and the rending crash of a car that couldn’t quite stop until the same much abused vehicle takes them off, usually 15 minutes later.”

Buster Mowbray: “We feel we’re at the peak of our popularity right now. As a group we have been getting more requests for public appearances than we can handle. And we have had reports from England, Australia, USA, and Canada about locally made recordings which have been successful …

“But some of the boys have families, others have increased business responsibilities. We feel that as amateurs we just can’t keep up the standard for ever, and it’s better to sign off while we’re at peak form. So that’s what we’re doing.”