Trevor had spent his life in the wings of theatres all over New Zealand, delighting as he watched performers on one of his stages, or a movie he was promoting unfolding on the silver screen. From the 1950s through to the 90s he was the what’s-on and how-to man in the city when you needed a stage, a decent hotel for a touring band, a venue, or a field to put a circus tent on.

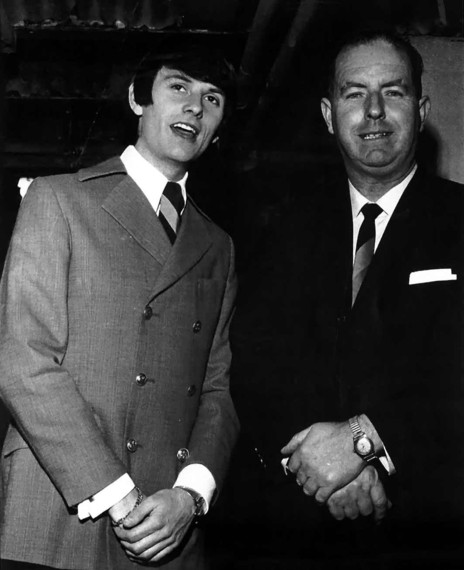

King scored a tour manager’s rare double, hosting the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

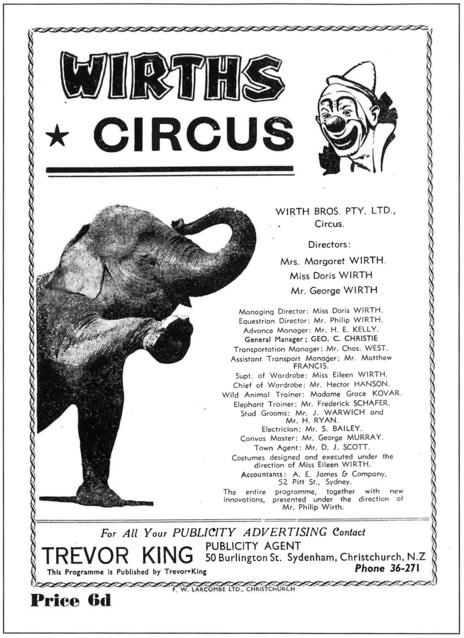

He promoted a grab-bag of popular styles for wide audience appeal, from pop, jazz, and rock ’n’ roll to variety, circus and opera. And as tour manager for individual performers to bands to large-group tours, he would be waiting in the wings to congratulate them at the end of their shows; he would be at their hotel first thing in the morning to make sure they caught their early flight. He spent a lifetime shining a light on others and scored a tour manager’s rare double with the Beatles, followed by the Rolling Stones.

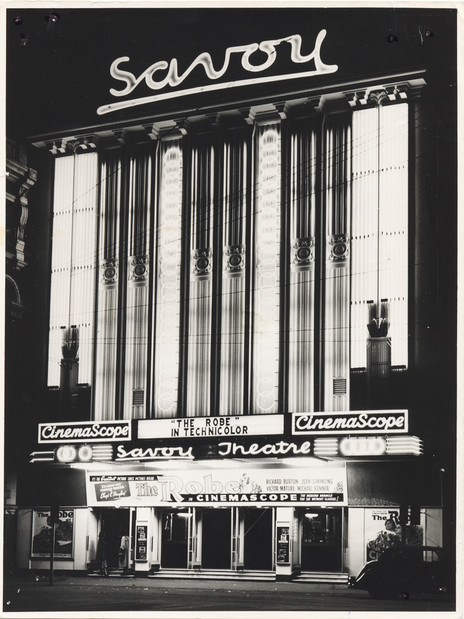

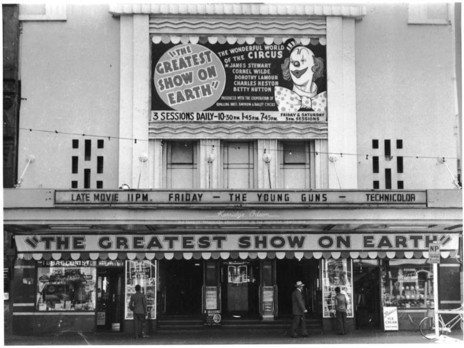

Born in 1924, Trevor Wesley King grew up in an era when every corner of Cathedral Square, the heart of Christchurch city, boasted a theatre with a grand façade, an alluring name, and billboards announcing the latest western, romance, comedy or thriller. He was a self-confessed nostalgia fanatic for stage shows and film.

As a lad in thrall with the magic of Hollywood, he earned pocket money as an ice-cream boy at his local suburban movie house, ironically called Kings, on the corner of Elgin and Colombo streets. The biggest perk was getting to see the films he loved for free. Christchurch was still holding hands with the “Motherland” then, and before lights out he and other ice-cream boys would sell cones and sweets from neck-slung trays to patrons waiting till the last minute to buy, so their ices wouldn’t melt while they stood for ‘God Save the Queen’. Other patrons preferred to light up, but they too had to wait until after the anthem.

His mother was a cleaner at the Regent and two of his brothers were ice-cream boys, with one progressing to the promotional role of pageboy, emulating those of J. Arthur Rank’s 1930s UK Odeon chain: uniformed pageboys wearing sandwich boards and handing out fliers.

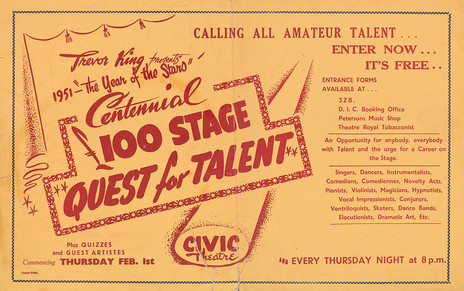

By 18 Trevor was managing the Tivoli Theatre and over the next couple of decades he managed some 12 city cinemas and their multiple employees. He was familiar with every theatre’s projector room, auditorium capacity, office layout, front-of-house and backstage lighting grid. And to the hordes of Christchurch children who enjoyed his 10am Saturday matinées, as well as competitions, variety entertainment and talent quests through the Chums Club he started, he was known as “Uncle Trevor”.

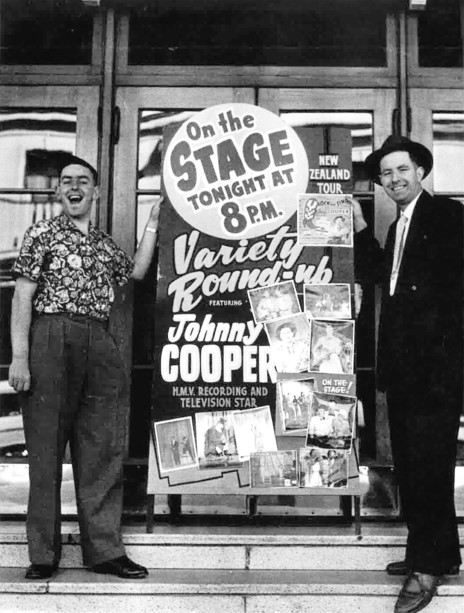

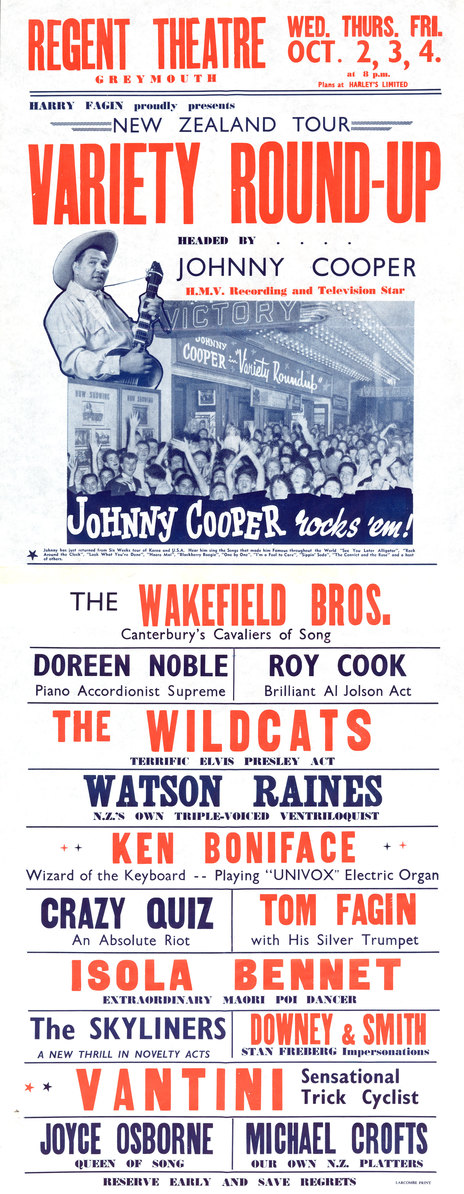

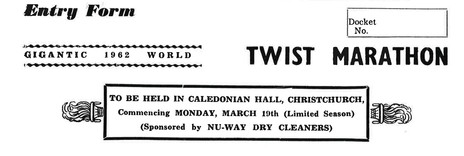

In the early 1950s he ran a series of packed-out talent shows at the Civic Theatre, touring talent-show winners to various towns and country centres. Oddly, he chose the nom de guerre of “Harry Fagin” for these shows, a hopeful and stereotyping nod to America’s successful Jewish movie producers.

Trevor had worked his way up through the various movie-house ranks, handing out fliers, being a message boy, storeman, circle doorman, caretaker by day and doorman-fireman by night. He was doorman and fireman at the Avon in 1947 when the Ballantynes department store fire broke and he rushed over to Cashel Street to help.

His long association with cinemas ended with the 1989 closure of the Avon Theatre on Worcester Street, but before that he had bought the Avon Milk Bar next to the theatre for his mother, and she ran it for before they both moved on to the Shirley Tea Rooms in New Regent Street, a handy setting to conduct business from.

In the glory days of cinema, “we managers wore evening suits, and the cashiers and usherettes had real uniforms.”

Until the 1960s, when television put a small screen in every home, dressing up and going to “the flicks” was standard entertainment fare. These glory days of cinema, Trevor wrote later, “provided an affordable sense of occasion, especially in the evening sessions. … After all, we managers wore evening suits, and the cashiers and usherettes had real uniforms.”

While he was a young territorial at the start of the war, he had had a sideline distributing promotional flyers and billposting, and this segued into advance promotion for shows and a hop, step and jump into full-scale promotion and tour managing. One of his first promotional contacts was with Tex Morton and the two remained friends till Tex’s death in 1983.

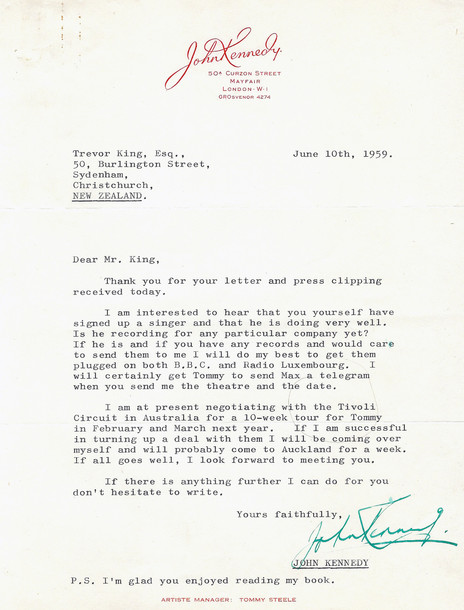

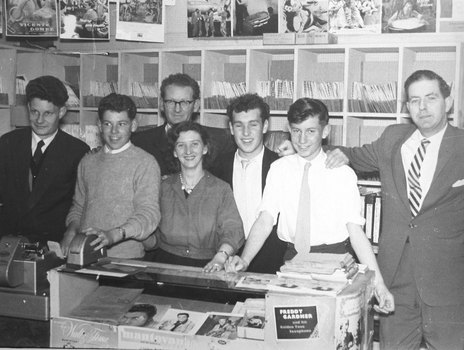

By the late 1950s and early 60s traditional Hollywood styles were making way for the explosion of movies by rock and pop stars, and teens were flooding box-offices for tickets to see Elvis or Cliff Richard or Fabian singing to them in huge Technicolor close-up. Trevor met many of the stars or their representatives while he promoted the movies.

As guest editor of Joy magazine in 1960 he wrote of his trip to Australia to meet entrepreneur Lee Gordon, promoter of US teen idol Fabian, whose movie he was screening to sell-out crowds at the Tivoli. Gordon also produced stadium extravaganzas. He invited Trevor to an opening night and an after-match dinner with the stars where he caught up with Johnny Devlin, among others.

“I was fortunate in meeting Lloyd Price, Tab Hunter, Frank Sinatra, Col Joye, Sal Mineo, Conway Twitty and the Platters. … I enjoyed talking to Sal Mineo about his new movie, The Drums Speak (the Gene Krupa story), and to the Platters about their rock ’n’ roll films, but they were all good to meet in person.”

His focus was also fixed firmly on the New Zealand music market, putting up-and-coming talent on the theatre stages and helping others in various ways. By 1958 he was tour-managing the Howard Morrison Showtime Spectacular, a show so popular its six-week booking extended to nearly 20 weeks.

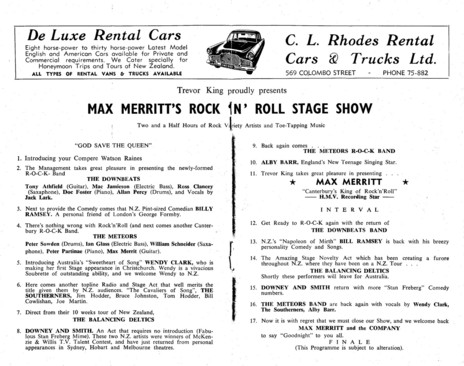

A year earlier he had started the Christchurch Teenagers Club, a Sunday dance, with Jim and Ilene Merritt, Max’s parents, in Railway Hall on Carlyle Street, Sydenham. The club had 300 members at the outset and this had grown to 1200 three years later. It was Max Merritt and the Meteors’ first gig. Max and the boys also ran their own Wednesday night dance, giving city teens something else to do other than hanging around the streets or doing the circuit of Cathedral Square in their Mk1 Zephyrs, Vauxhalls and Ford Prefects.

Trevor King managed Max and the band until 1963, as well as doing groundwork for other rising stars, such as Ray Columbus and the Invaders, Peter Nelson and the Castaways, and Dinah Lee. In his article for Joy magazine he wrote there was “no reason why, with good promotion and training, New Zealand entertainers should not be just as successful as most of the stars I have met here and abroad.”

Over his working life Trevor King was plugged in to every media outlet.

Over his working life Trevor King was plugged in to every media outlet and was sought out in return for comment. By the time of his retirement in his late 70s, he was keen to find someone to write his biography. No ghostwriter emerged, so he put together his own smallish (76-page) book of facts, photos and anecdotes. Called King of the Road, he gave it out to family, friends and business associates, and a copy is held in the National Library in Wellington.

His devotion to everything about the world of theatre, particularly in 1950s Christchurch, was no more apparent than in his own descriptions:

“… the Crystal Palace, with its distinctive tower inspired by Wren’s St Mary-Le-Bow church. Built in 1918, it boasted a 20-piece orchestra to accompany the films and variety shows”; “… the lovely little Plaza, with its elegant twin marble staircase”; and the “grandest of them all, of course, was the 1600-seat Regent, with its atmospheric Spanish interior and night sky ceiling.”

In 2003 I was visited at The Press by this tall, elderly, besuited gentleman with a twinkle in the eye and a tale to tell. I’d been out of the country for 20 years when he was most active and was unfamiliar with his work, but no matter. Trevor came armed with some research material: two massive packages stuffed full of publicity brochures, receipts, letters of thanks and commendation, references, photos, typewritten notes, “to whom it may concern” copies and handwritten addenda, all wrapped up in old movie posters and tied up with string. And this was only part of it what he had at home, he assured me.

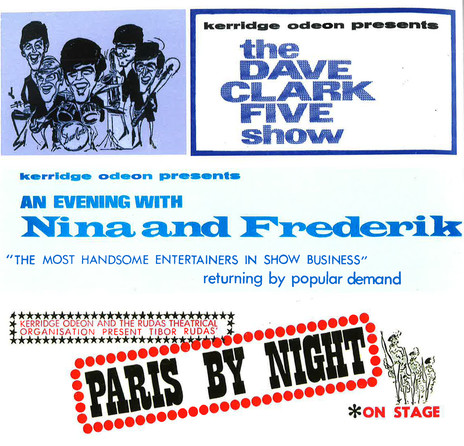

His client list was comprehensive, and names included the Glenn Miller Orchestra, Dave Brubeck Quartet, Engelbert Humperdinck, Pointer Sisters, Magic Johnson, Pat Boone, Village People, George Benson, Chubby Checker, Nina and Frederick, the Dutch Swing College Band, the Seekers, Cliff Richard, a Danish gymnastics team, Andy (‘Donald Where’s Your Troosers?’) Stewart, and violinist Yehudi Menuhin.

New Zealand “royalty” Kiri Te Kanawa, Howard Morrison, Inia Te Wiata, Max Merritt and the Meteors, and Ray Columbus were in the pack among others, and many of his local clients gave their time freely for his charity benefits.

Trevor invited me to his Spreydon home to view more of his memorabilia. The walls were a portrait gallery and honours board, with signed portraits of thanks, side-by-side shots of him and his stars, and show posters. His entertaining chat was redolent with talk of fees, dates, and audience details, and the anecdotes came thick and fast.

“Ray Columbus was a nice wee boy at the Avon Theatre when I was managing there. His late mother used to manage the ice-cream bar. When he grew up he asked me to be his manager around Christchurch. He lives in Auckland now, but whenever he comes back he always comes to see me. [“Trevor King calls it a day”, The Press, 24 Feb 2003, p.C7]

“Nat King Cole? I was with him in Auckland. Course, I was a fan of his. He was a wonderful man – that’s how I got that photo signed.”

Acker ‘Stranger on the Shore’ Bilk came with the Paramount Jazz Band. A favour backfired the morning after the show when Trevor packed the suitcases for Bilk, who was still sleeping off the effects of a long after-show party, and sent them on to the airport without realising he’d packed Bilk’s travelling clothes. A sprint to a nearby menswear shop and some size guesswork solved the problem.

Gene Pitney was “quite natural and unpretentious”, the Vienna Boys’ Choir a special favourite.

Twice he toured the “quite natural and unpretentious” Gene Pitney. One night Pitney found a fan hiding in his dressing room before the show. She had shimmied up the fire escape. He gave her a kiss and a hug, and escorted her swiftly out the stage door. Louis Armstrong, another client, gave him a letter of introduction to Muhammad Ali. The photo of them together in the boxer’s LA gym was on the wall, too, near Cliff Richard and Judith Durham.

The Vienna Boys’ Choir was in pride of place – and therein lies a tale.

They were a special favourite. To him they were “a happy group of youngsters” and to them he was Uncle Trevor. He worked with the company nurse, arranging hotels and meals for the group, and the pair grew close. The choir director gave him a return ticket to Europe as a thank-you, and over the next six weeks he and Nurse Helm talked marriage. Sadly, he found he was not keen to leave home, while she wanted to stay in Europe, so they parted. Trevor remained unmarried the rest of his life, doting on nephews and nieces instead of children of his own.

Trevor King spent nine months of every year living out of a suitcase by his “have bag, will travel” motto, but he was grounded in the south, a man of the city.

He grew up in Burlington Street, Sydenham and attended Sydenham Primary School and Christchurch Technical College. He lived in the family home for 50 years and ended his days in the retirement villa in nearby Spreydon, outliving all five of his siblings.

The Press quoted Christchurch actor David McPhail as saying that he was “a friend to many of the great names … Trevor lightened the Square. He made it a place where Hollywood hit High St’’. And John Dix, author of Stranded in Paradise, called him “a true gentleman” and “one of a kind”.

He was still organising a few tours into the 2000s, including a Welsh male-voice choir, Al Jarreau, John Rowles, and a five-month nationwide tour for an Australian production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. One of the dwarfs (Grumpy or Dopey, perhaps?) proved a tad difficult to wrangle, attempting to sell his rental car and take the funds home, but the police nabbed him at the airport.

Trevor King loved his showbiz life, dealing with everyone from usherettes and sound techs to his international stars and other producers. Into his later years his promotional brain was still buzzing away and even in 2006 he was offering written advice to such friends and clients as Ray Columbus.

In his later years his promotional brain was still buzzing away.

In 2003 he wrote to me three times in his careful hand, once including his poem, a paean to cinema titled “Memories of a Nostalgia Theatre Manager”. It contained these two lines: “How strong was the Enchantment / How willingly I fell …”

In the foreword to King of the Road he writes: “It’s been a magnificent journey, which I would so quickly do again if I had the opportunity. To all those who have been involved with my show business career I thank each and every one of you from the bottom of my heart.”

Uncle Trevor was recognised in many quarters for his lifetime’s work. In 1992 he was honoured with a Queen’s Service Medal, and before that had received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the New Zealand Entertainers & Operators Association (1983) and a New Zealand Commemorative Medal (1990). Christchurch City Council conferred on him a Civic Award in 1998, and in 2007 he was inducted into the ROCKONZ Rock Hall of Fame.

After a lifetime devoted to the magic of entertainment, Trevor King slipped quietly out the stage door, remembered for the integral role he played in the celluloid reel of his own star-studded life.