AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

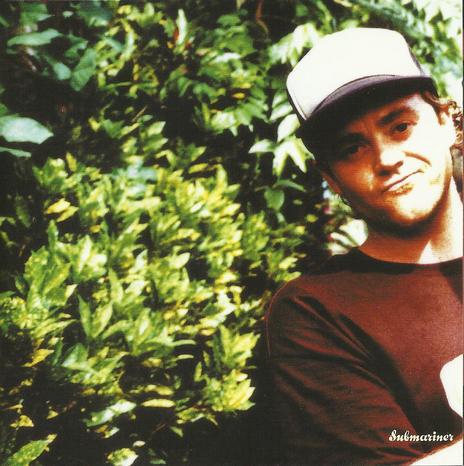

Andy Morton

aka Submariner

The son of an electrical engineer father and a mathematician mother, between 1997 to 2004 Morton – once described by Mark Williams aka MC Slave as “one of New Zealand’s finest producers of the last twenty years” – crafted beats, recorded demos, and mixed and produced albums for a generation of New Zealand hip-hop, jazz, and rock artists who shifted the local musical landscape. During this period, he helped usher in a sound that accurately expressed the culture, stories and experiences of the South Pacific, as integrated with the sonic frameworks laid down by the North American, British and Caribbean musicians they drew inspiration from.

“I lived in the States until I was nine, so I’ve always been aware that we couldn’t just copy what they were doing there,” Morton says. “We’ve got our own thing in New Zealand, and we should tell our own stories. We shouldn’t try to imitate their world; we should be in our own world. Someone can influence you, but you shouldn’t copy them. For me, it’s always been important to make a unique contribution. There are plenty of imitators, so if you don’t contribute, what’s the point?”

Morton’s journey towards contribution began after he moved from Texas to Mount Eden in Auckland with his mother. “I got really into synthesisers, keyboards, and electronic sounds. I would save up my paper run money, buy music gear out of Trade & Exchange magazine.” He’d learn the equipment inside out, sell it off, and repeat. By reading through cheap music magazines, watching VHS tapes, and talking with the staff at music stores, Morton expanded his musical vocabulary. He started playing the drums, and during a lesson, was introduced to drum machines. “After my teacher showed me a LinnDrum, I thought that’s what I want to do. I didn’t get a drum machine for three or four more years though.”

Morton would save up his paper-run money and buy music gear out of ‘Trade & Exchange’ magazine.

By his mid-teens, Morton had a simple home studio in his bedroom and, with a friend, would use a 4-track tape recorder and a basic sampler to make beats. “He would come over, and we would make loops and put samples over the top, then he’d put vocals down.”

Fun fact: The friend was Zane Lowe.

At the end of sixth form, Morton told his mother he wanted to be an audio engineer. “I think I had been into it all for long enough that she thought I would make something of it, and I had good enough grades to still go to university if I wanted to.” He left school and started studying audio at SAE (School of Audio Engineering). “I remember wanting to get into doing the soundtracks for adverts. I do adverts now, but it took me a very long time to get into. I’m still trying to get into it really. It’s a very hard business.”

SAE had a studio the students could use, and they offered overnight sessions. Morton would ring up every day and ask if anyone had cancelled their booking, then bring his keyboards and sampler in with him. “You were only supposed to have one to two overnight sessions a term, but I would have about ten.” One of his classmates was Chris Sinclair, who was already doing engineering and production work for local independent record label Deepgrooves. “We hung out a lot because we were both just more serious about it, and finding our way into the music industry.”

Fittingly, Deepgrooves is where some of his first production work landed, with Babel's A is for atom – a shuffling space-funk collaboration with vocalist Kieran Cooney that proved popular with student radio – and reggae singer Jules Issa’s 1995 debut album Found In You.

“SAE is where I got interested in dub and reggae. I would listen to Stinky Jim and Dubhead’s shows on bFM, which was big for me. It gave me a new focus musically, and Jules became my connection to that. It was difficult though, because Jules and Steve (her husband at the time) had a real traditional reggae approach, and I wanted to do something more modern, in a trip-hop style like Massive Attack,” Morton says. “With music, you find a way. All your influences come together to make you who you are, and you don’t really start where you finish.”

In 1996, the now-defunct York Street Recording Studios invited Morton to start working inside their premises. “I ended up in this back room, started paying rent, and people started coming in. After contributing some beats to Dam Native’s debut album Kaupapa Driven Rhymes Uplifted (KDRU) in 1997, he began working with South Auckland street rapper Ermehn. In 1998, he produced Ermehn’s debut album Samoans: Part 2 for Deepgrooves. Just under a decade later, music reviewer Grant Smithies wrote in his 2007 book, Soundtrack: “[Ermehn’s] street soldier stories are bleak but skilfully told, and give insight into the hard life many rappers invent for themselves, but this man seems to have actually lived.”

“The great thing with Ermehn is he just wanted to do the lyrics,” Morton says. “He didn’t want to have anything to do with the music. If he liked the beat, it was cool. He’d just come in and drop his verses. I loved that he trusted my ear. The project was very low budget. We had one 16-track reel, which was 15-20 minutes long. We kept it simple, and it worked.” The experience of working on Samoans: Part 2 taught Morton how to produce an album, and during the sessions, he met someone who would become a close friend and collaborator of his, the legendary Auckland DJ Manuel Bundy.

After Morton met Manuel Bundy, things changed.

After Morton met Manuel Bundy, things changed. “The connections I made through Manuel were bigger than what I learned [while making Samoans: Part 2],” he says. “Manuel brought in Bill [Urale, aka King Kapisi], Bill brought in Che Fu and all the dudes in the Token Village band, including Sani Sagala, later known as Dei Hamo. Around this time, the signatures of Morton’s sound as a beatmaker and producer began to crystallise fully.

Morton told Williams during an interview for Red Bull Radio, “I liked things that were about layers of sound ... [hip-hop artists like] Public Enemy, De La Soul, The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, and Antipop Consortium … It’s that Prince Paul production technique of layers and samples, but I also liked to keep things simple as well.”

Morton’s studio became a community meeting spot. “People would come to smoke weed, and we would practice DJing, scratch, and make beats.” In those days, Morton never really left the studio. Eventually, Bundy told him to come down to the club he was DJing at that night. “It was a real eye-opener for me to go to the club and see people dancing,” he admits.

Morton was already collecting records and could scratch and mix, so with some further encouragement from Bundy; he started DJing in clubs. “It took a couple of years before I started doing it regularly. I looked through my old accounts books a few days ago, and I made so little money in those days. I can’t believe I survived. Sometimes I make more money in a month now than I did in a year. The thing is, it was a cheaper world, and I was doing what I wanted to do. I was young, hungry, and spending $50 a week on rent. I didn’t care if I didn’t have any money.”

For Morton, those years served as his unofficial education. “Instead of investing money in going to university, I was going to invest money in something I really wanted to do, which was make music with these people.”

One of the first people he started recording with after Ermhen was Urale, who introduced him to Kas Futialo aka Tha Feelstyle. They all worked together recording demos for Urale’s landmark debut album Savage Thoughts (eventually released in 2000) before Kapisi decided to complete the record with a different set of musicians and producers at The Comfort Zone and Helen Young Studios. Those sessions laid the groundwork for when Morton and Futialo hit the studio together in the early 2000s to record their masterwork Break It To Pieces.

After Samoans: Part 2, Morton’s next two major projects were working on Che Fu’s 2b S.Pacific album and Mark de Clive-Lowe’s Six Degrees. “As well as hip-hop and reggae, I was passionate about jazz and electronic music, so it was great to work on both projects,” he says. Both landmark releases, they helped solidify Che Fu and De Clive-Lowe as major figures within their respective musical worlds.

After ‘Samoans: Part 2’ Morton worked with Che Fu and Mark de Clive-Lowe.

As Morton told Williams during an interview for Red Bull Radio, “[2b S.Pacific] just captures a real New Zealand vibe and fuses a lot of things. The reggae, the topics that came up [in the songs], just the general vibe.”

“There was a real honesty and freshness to the songs Che did in that period. I was really pleased with them even though they were rushed. I was just happy to be the guy who worked on it.”

In the late 90s, Dunedin songwriter Shayne Carter moved to Auckland, where he became deeply inspired by avant-garde electronica, leading to the 2001 release of I Believe You Are A Star, his first proper album as Dimmer. On the advice of Jim Pinckney aka DJ Stinky Jim, Carter approached Morton about helping out with production for the album.

“Shayne is a poet. He can weave multiple stories into one song. I’ve always liked rock music, but that record is the main thing I’ve worked on in that world,” Morton says. Around the same time, Morton contributed keys, production and engineering to several songs on Bic Runga’s 2002 album Beautiful Collision.

While he was working on I Believe You Are A Star, Morton and Futialo ramped up their efforts on Break It To Pieces, Futialo’s first album as Tha Feelstyle. With Break It To Pieces, Morton took the lessons he had learned from demoing for and producing on Samoans: Part 2 and 2b S.Pacific and took his overall vision to the next level. Futialo had been through the wringer a few times as well, and they came out with a masterwork that combined English and Samoan rapping and singing, and a production sound that perfectly balanced Futialo’s heritage, humour and influences.

In 2004, they released it through Can't Stop Music, a label they created with Malcolm Black, winning considerable critical acclaim both here and abroad from the likes of UK radio DJ’s Benji B and Gilles Peterson. “Break It To Pieces, 2b S.Pacific and Samoans: Part 2 are a trilogy in my life, but they might not be in anyone else’s,” Morton says.

“Kas [Futialo] is non-commercial. He’s an actual artist, and that’s what I like,” he continues. “That album came out exactly how I wanted, and I was so happy. We bankrolled and backed it, so we had the freedom we needed. It’s my most complete record, and I’m so proud of the fact we retained enough control to get it where it needed to be. We didn’t have to worry about it being commercial or on the radio. It was never tainted.”

A year earlier in 2003, Morton launched a regular club night called The Turnaround with Bundy and another DJ friend of theirs, Cian O'Donnell aka DJ Cian. Having spent some time learning graphic design, Morton would create the posters and handle the setup and running of the sound system, and O’Donnell would look after promotion and bookings. “Manuel [Bundy] would deliver on the night, and lend his name and experience to the event,” Morton says. It became one of the most important regular events in the city during the 2000s, and inspired several generations of Auckland hip-hop, soul, funk and jazz acts including Opensouls, Tyra and The Tornadoes, and the extended Young, Gifted and Broke artist collective.

“I love the new generation of local talent,” Morton says. “I feel a real kinship with them. They’re exactly like we were in the late 90s, but it’s like it skipped a mini-generation, then those cats took what we were doing and ran with it. They really turned it into something. Tom [Tom Scott from Home Brew] is funny, topical, current, has things to say, and has a purpose.”

“I love the new generation of local talent – I feel a real kinship with them.”

After Break It To Pieces, Morton pulled back from creating albums but continued to remix for Fat Freddy’s Drop, Recloose, Salmonella Dub, Bic Runga, and others. He has also added his touch to the odd artist project here and there, most recently for Sola Rosa. “I got disillusioned with the industry,” he admits. “Often, you have people in your ear saying, ‘Why aren’t you more successful?’ When you’re on TV, people start assuming you should be rich, and it can get very confusing. The reality for me is I do music for love; I don’t do it for profit.”

In 2008, he helped Riki Gooch mix his first Eru Dangerspiel album and occasionally joins Gooch on stage in the big band playing keyboards. Four years later, he provided Home Brew with mastering assistance for their self-titled debut double album.

These days, Morton’s main focuses are paying the mortgage through commercial audio work and DJing and spending time with his family. In the greater scheme of things, he comes across as happy and content with life.

“I bought a whole bunch of new gear recently and have been reorganising my studio,” he says. “I want to do something else, but I’d either have to do something myself or find someone new who excites me.” Here’s hoping he does.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air