AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

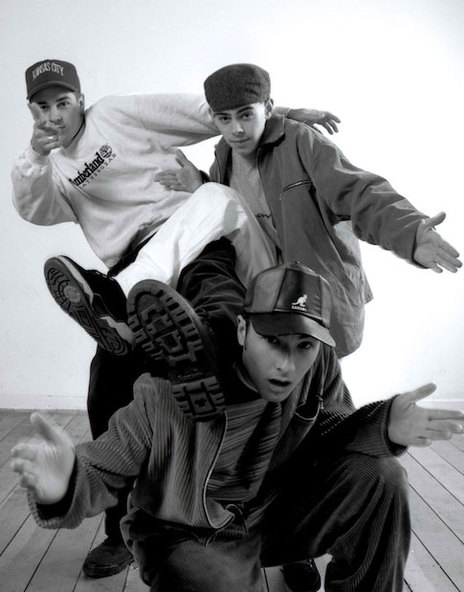

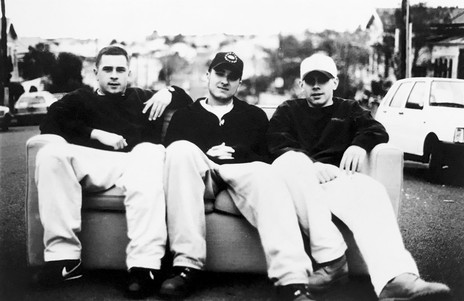

Urban Disturbance

The story of the group starts with two 12-year-old boys at summer camp (Camp Olympia). The first of them, Rob Salmon, was playing a new cassette he’d bought, Paid In Full by Eric B and Rakim, to the other kids in his cabin when he heard a knock at the door.

“This guy walks into the cabin rapping all the lyrics to ‘Paid In Full’ – ‘thinking of a master plan ...’. I was like, wow, who’s this guy? And he said, ‘Hey, my name’s Zane.’ I asked him how he knew the music since it wasn’t like hip hop was common knowledge at that time. He was like, ‘come back to my cabin, I’ve got a whole bunch of tapes of stuff I’ve recorded off the radio.’ It turned out he also had these massive big books where he’d cut out articles from The Source and NME about hip hop. We became friends after that.”

Leaders of Style

The friendship between Zane Lowe and Rob Salmon solidified when they both attended Auckland Grammar School the following year and began teaching themselves how to make hip hop with the limited means and knowledge they had at their disposal. They would battle over landline phone calls with their pause-button tapes: cut-ups created by recording different snippets of famous tracks one after another, until they had their own roughly constructed remixes. Salmon admits that Lowe’s were almost always better, showing an early sign of his production talents.

Gradually each of them found their own focus within hip hop. Salmon taught himself how to scratch records and went on to the win the Auckland round of the DMC DJ battles two years running (1990-1991). Meanwhile, Lowe began learning how to make beats. At first, he just used what he had at hand – a cassette 4-track recorder. This meant that when he sampled a beat, he had to record a bar of it and then rewind the original recording back to the top so he could record it a second time, thereby laboriously adding each new section so it came in at the perfect spot to follow on from the last.

Lowe and Salmon would battle over landline phone calls with their primitive mixes.

Fortunately, Lowe soon made contact with others who had the same interest, but who had the gear needed to create beats more smoothly. The first was schoolmate Andy Morton, who had an Akai sampler and keyboard. Morton would later be known as Submariner and work on breakthrough albums by Che Fu and Tha Feelstyle. Next, Lowe met Graham Bollard, who wrote music professionally (he created the theme tune for Shortland Street). Bollard had a professional recording set up which he allowed Lowe to try out.

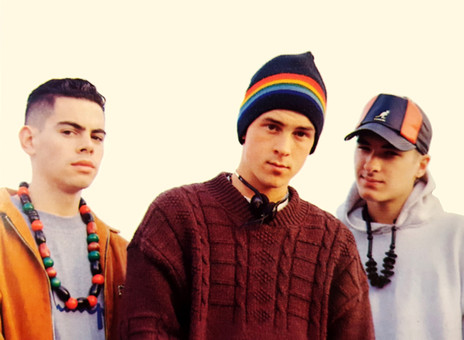

It was inevitable that Lowe and Salmon would decide to form their own group and they initially chose the name Leaders of Style. Salmon now finds it funny to recall their naivety and youthful desire to be on trend with what was happening overseas in hip hop.

“I called myself DJ Fade. Back in those days, I had the gelled up Kid’n’Play flat top and I was fully into wearing African medallions. Zane was MC Blaze ... We did our first Leaders of Styles gig together at a party called Quest which was at Club Roma on Queen Street, just up from the Civic. Zane came out all hardcore like Chuck D with a big African coat and a LA Raiders cap and I’m wearing black cycle shorts because I had a Spike Lee thing going on. I think that would’ve been around 1990-1991 and that was the beginning of the Leaders of Style.”

The group expanded to a three-piece after Lowe met another young hip hop fan, Oli Green, who attended a nearby school, Seddon High. Green remembers that he also got into rap music at an early age.

“I came up through all that classic punk like Dead Kennedys and then got into hip hop. We were just assaulted: Public Enemy, NWA, De La Soul. Though New Zealand was pretty bereft in everything. [In Auckland] there was just one hip hop show [on bFM] and we used to listen to it every week. Then we’d be using my mum’s speaker on-off switch on her stereo for scratching and shit. There was one Raiders hat that got handed around six guys and swapped. Someone would get a pair of Nikes and everyone would go around to their house and look at them. It was nuts.

“I was just one of those white kids that was obsessed with black music and culture, so I was keen to get out of the country and ended up living with my dad in San Diego for a year. That was a bit of a fuck up. I was a white kid who liked hip hop in a school that was all about surf culture. But it got me further into it. I came back and had a really affected American accent. I think Zane heard that and just thought, yeah, that might actually work. The whole thing was always Zane. While we were rolling weed on record covers, he was studying the liner notes.”

Leaders of Style had their first official release through a track on the bFM compilation Freak The Sheep Vol.2 (1992). Their contribution ‘Real Swingers’ caught them in their early party-rap mode and got them attention across the student radio network. This was in the era when rap groups would play between DJs at dance music events, and Leaders of Style focused on hyping up the crowd, doing callouts or spraying silly string into the audience.

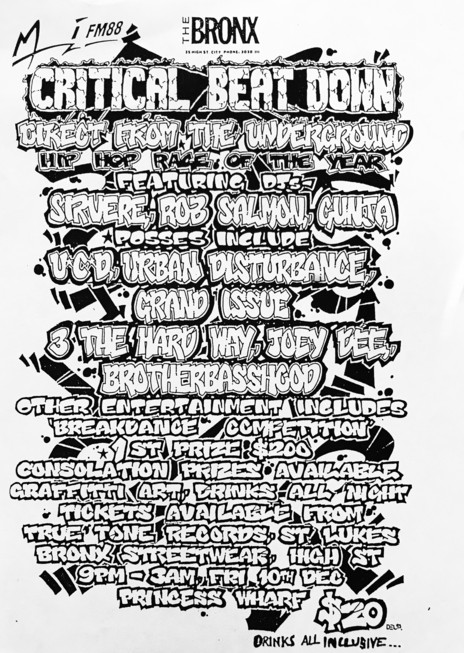

They gained some decent support slots in these early years, opening for Headless Chickens at the Powerstation and supporting Ice T and Public Enemy at the Auckland Town Hall. Lowe showed an early sign of his networking prowess by befriending US rapper Del The Funky Homosapien after they played with him at K Rd club The Staircase, and the pair continued to talk over the phone for years afterwards.

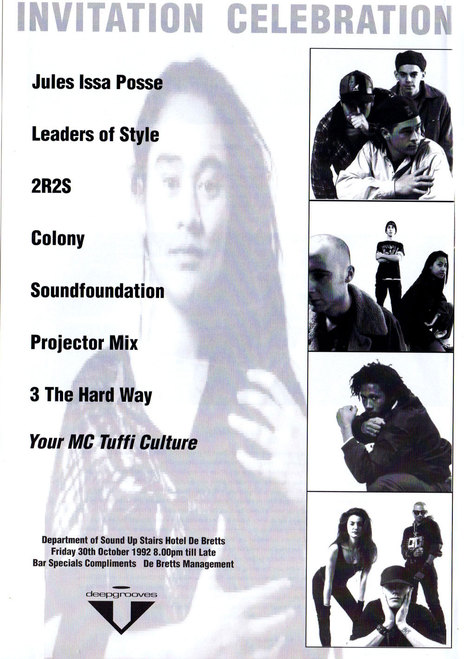

The group’s hard work led to the trio meeting up with Kane Massey from Deepgrooves Records, who offered to put their new track, ‘No Flint No Flame’, on a compilation they were doing (Deep In The Pacific of Bass, 1992). The song title came from a situation in which Green’s girlfriend had noticed that a Zippo lighter someone was trying to use had no flint and the idea was taken as a metaphor for not getting ahead of yourself.

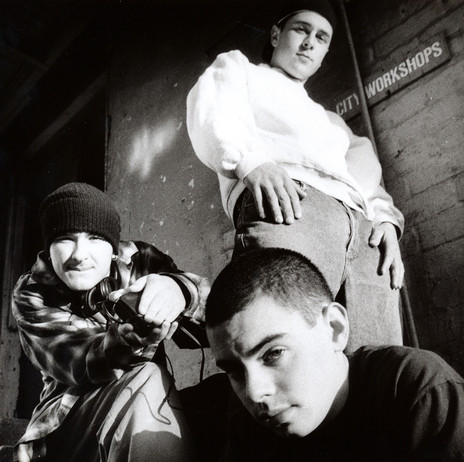

Urban Disturbance

Green and Lowe’s skills as rappers grew to the point where they began to push beyond the simplicity of their early party raps, dropping the party clichés for tautly flowing raps, that could switch gears from super-fast to slow and emphatic within a single verse. In order to be taken more seriously, the trio decided to change their name to Urban Disturbance, a phrase that legendary local DJ Manuel Bundy had used for an event, but was happy for them to take up.

Urban Disturbance’s First release on Deepgrooves got within a whisker of the Top 40.

Urban Disturbance re-released the track ‘No Flint No Flame’ as the lead track on an EP the following year through Deepgrooves. The beats across the six tracks were uniquely modern, especially within a local scene that perpetually seemed a few years behind the US, and there was even an opportunity for Salmon to flex his turntable skills (on ‘... And Into The Hands Of Chaos’). NZ On Air funding allowed them to make a decent music video, which gained a few spins on national television. They got within a whisker of the Top 40 at No.42. Not bad for a first release, though unfortunately, this would end up being their only appearance on the charts.

They continued to expand their live following by playing at the Big Day Out and touring throughout the country with bands including Supergroove and Hallelujah Picassos, while also putting their minds towards doing a full-length album. Salmon believes one reason Lowe and Green put in such hard work to get their tracks perfect was because they felt they had a point to prove.

“They were definitely really looked down on because both of them were Ponsonby kids in a scene dominated by Polynesian crews. It’s funny because I’m actually half-Niuean, so I guess Urban Disturbance did actually have a Polynesian aspect to it. But there was a lot of people hating on us I think at that time. Another reason was probably that the three of us had it quite together, whereas a lot of the early groups had quite scattered, fragmented ideas. I did feel like Zane and Oli were really talented, gifted guys and they stood miles ahead of most of the competition.”

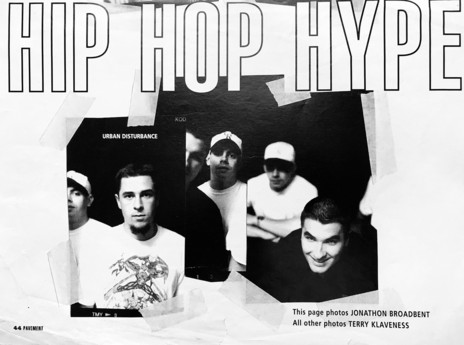

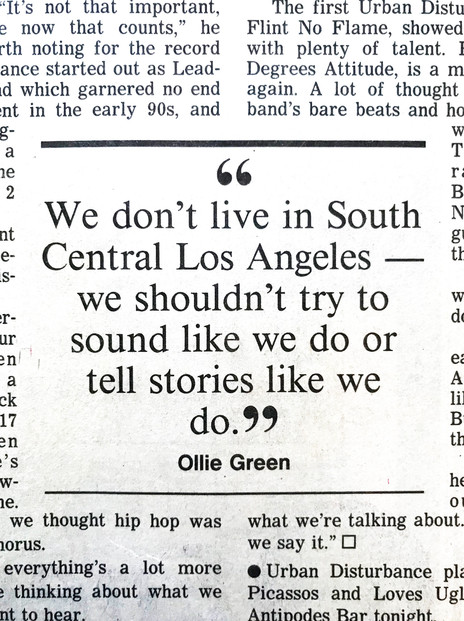

The 17 brand-new tracks on 37° Lattitude (1994) were a testament to just how much Lowe and Green had evolved their rapping style, dropping Americanisms in favour of local topics and laying down rhymes with a remarkable sense of flow and style. Green recalls they put a lot of pressure on themselves during the recording sessions.

“When we did that album, I was pretty serious about it. It was a mad work rate, we were doing a track a day. We’d go in, write it, make it, mix it, and go home just to sleep … Everyone in that room was fucking about it. We were really critical of each other. It was like a battle every time we went in. It was really good. We wanted to have a lyricist’s lounge scene – I was really into the avant-garde Left Coast rap that was coming out at the time. The Pharcyde were a mainstream version of it, but there was also Freestyle Fellowship, Abstract Rude and all these weird crazy jazz rappers who didn’t give a fuck about rhyme schemes or whatever. I went down that path quite heavily, maybe to my own chagrin, but it was really fun.”

In order to increase the creative pressure, they brought to the studio some of the best rappers and musicians on the local scene at that time. Danny D (from Dam Native), Hame (aka Hamish Clark from Beats’n’Pieces), and guitarist Joel Haines all showed their skills over a big pounding beat on ‘Relay’. Equally impressive was ‘Figure This Kids’ with its catchy chorus and a guest verse from Sani Sagala (aka Dei Hamo). The track is a call to arms for the local hip hop scene and ends by listing all the main players in the scene at the time: Dam Native, Rough Opinion, GAB, Mad Coconuts, DJ Sir-vere, Manuel Bundy, DJ Rob, Cut Five, Lunatic Click, Dark Tower.

Urban Disturbance were recognised at the 1994 NZ Music Awards, winning the Most Promising Group category.

The pounding beats on these tracks were balanced out by other sections of the album where Lowe’s production drew from the jazzy, downbeat style that was popular at the time. ‘Custom Made Thoughts’ even featured jazz talents Nathan Haines and Ben Harrop (who each ran their own combo at the coolest of local clubs, Cause Celebre). Jazz also underpinned standout track, ‘Robert Jane’, which showed Lowe and Green rhyming with precision even over a slower paced beat.

Things felt like they had fallen into place for Urban Disturbance with the album garnering great reviews and support from a new music television channel in Auckland, Max TV, which put their videos for ‘Impressions’ and ‘Robert Jane’ on high rotate (Lowe became a VJ on the station). They were recognised at the 1994 New Zealand Music Awards, winning the Most Promising Group category. Around the same time, their labelmates 3 The Hard Way had a hit on both sides of the Tasman with their single ‘Hip Hop Holiday’ and so were able to take Urban Disturbance with them for a tour across Australia.

Making Sense of It All

The year after the album came out, Rob Salmon left Urban Disturbance to pursue his work as a DJ. Since the start of the group, he’d been working around the clubs of Auckland after winning a Wednesday night competition that gave him his first slot at The Box back in 1990. He’d initially included a large amount of hip hop and R&B in his sets but now found himself changing with the times and moving towards house music. At the end of 1995, he made the bold decision to try his hand in the New York club scene. He not only succeeded in becoming a heavily booked DJ but also moved into production, releasing two huge singles with New York dance producer Rob Rives and creating a track for an album of Human League official remixes.

Undeterred, Lowe and Green returned to the studio to start work on a new album. However, they’d made such a definitive statement on their debut release that Green felt them struggling to find the same enthusiasm.“We looked at each other and were like, rap is a resistance music, what are we angry about? That we didn’t have enough milk in the fridge that morning? We had to eat the crust because the Vogels ran out? It started to feel like we were just doing it to do it.”

In end, the gradual demise of the group came as little surprise to Green.

oli Green: “We looked at each other and were like, rap is a resistance music, what are we angry about?”

“It was really organic actually. We had rinsed New Zealand a little bit, there wasn’t really anywhere for us to go. There wasn’t anyone going, let’s take you to America, or even let’s take you to Australia. We did start on a second album and there’s probably still five cuts floating around from those sessions, a couple of which were quite good. It was going to be called ‘The Walkman Chronicles’, that’s how long ago it was – we all still had Walkmans! But I needed to make some money, so I went off to work in advertising. Then Zane went on to produce Dam Native so I rapped on a cut for that which they never used. In the end, it was all just a bit too hard to keep going. It seemed a bit pointless and I couldn’t see the way out, but Zane had a fucking plan didn’t he? Went off and became the most famous person I know – what a cock! Hehe! Left us all staring at that same pair of Nikes around at that dude’s house in Grey Lynn.”

Green went on to become an advertising creative director, before directing commercials, short films and music videos. He’s also written a couple of books, The A-Z of Fucking Everything and You Can’t Give Vodka To A Baby and Other Parenting Myths.

Urban Disturbance may have gone, but they left a resounding impression on some of those who came up in their stead. One prime example being DJ/producer extraordinaire P Money, who points to them as an inspiring presence on the local scene when he was first taking an interest in hip hop during his early teen years.

“The production, rhyming and scratches were dope. I had the No Flint No Flame EP on cassette when I was in high school and then bought the 37 Degrees album on CD when it dropped. I remember a random after school TV show that they featured in (maybe when they were still called Leaders Of Style?). Watching Zane and Oli rap and talk about hip hop made it even more relatable to me. They were cool. Rob’s scratches were always super funky and precise. That’s what first caught my eye. I already wanted to be a DJ so his example was one that I looked up to. I remember they opened for Public Enemy at the Town Hall and Rob was cutting up ‘It Takes Two’ – that memory always sticks with me. I wanted to be doing that!”

In subsequent years, the notoriety of Urban Disturbance has been overshadowed by Zane Lowe’s other successes, first as a VJ on MTV Europe and then as a radio disc jockey on the BBC (where he became one of their best-known presenters). In 2015 he began hosting his own show on Apple’s international radio station, Beats 1.

THE NOTORIETY OF URBAN DISTURBANCE HAS BEEN OVERSHADOWED BY ZANE LOWE’S OTHER SUCCESSES.

However, he has kept his hand in as a producer over the years. Before he left for the UK, Lowe had started his own group, Breaks Co-Op, whose downbeat 1997 album Roofers produced a minor hit in ‘Sound Advice’. The project also featured his old collaborator, Hamish Clark, and led to two further albums that made the NZ Top 20: The Sound Inside (2005) and Sounds Familiar (2014).

Eventually, Lowe also produced beats or co-wrote with some of the biggest names in the worldwide music scene, including Sam Smith, Future, Tinie Tempah, Chase & Status, and Example.

However, Lowe’s other work does nothing to diminish Urban Disturbance’s important place in the history of local hip hop and that is something Rob Salmon has come to appreciate more over subsequent years.

“It was a really important part of my life and I had a lot of fun. You just don’t realise when you’re doing these things that it might end up being seen as a pioneering moment in New Zealand hip hop. So mainly I just look at as an exciting time. Though it’s nice to think we might’ve inspired the next generation of people.”

Zane Lowe's father is Derek Lowe, one of the original Radio Hauraki pirates.

NZ Herald article on Zane Lowe, 2018

RNZ: Urban Disturbance in Broadcasting House, April 2010

RNZ: Zane Lowe: Vocal and passionate about music, January 2105

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air