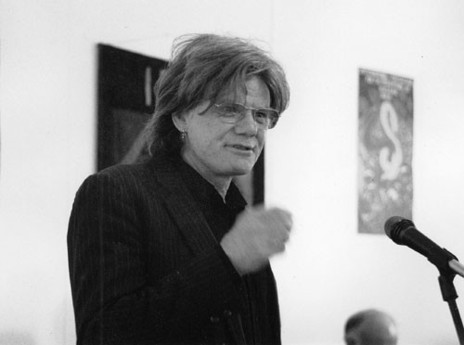

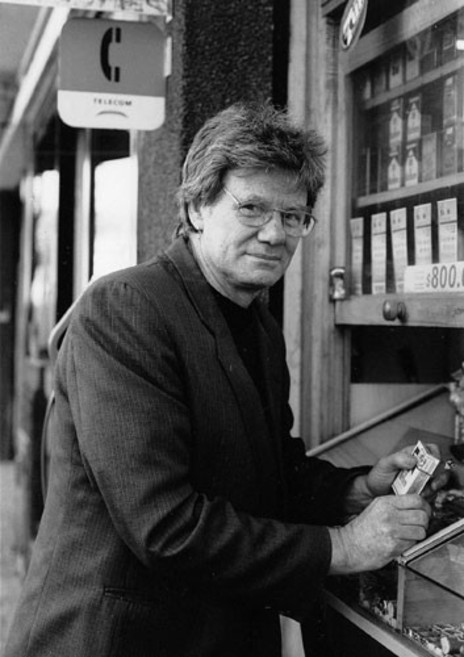

Arthur Baysting was involved in the earliest Red Mole performances at Carmen’s Nightspot, Wellington. In 1977 it was a place frequented by a mix of sailors and students. According to Baysting, Alan at first “gave his lyrics … rhymed poetry … to the musicians” for them to set to music but “he quickly became more proficient” at telling them what kind of music he imagined as accompaniment for his words.

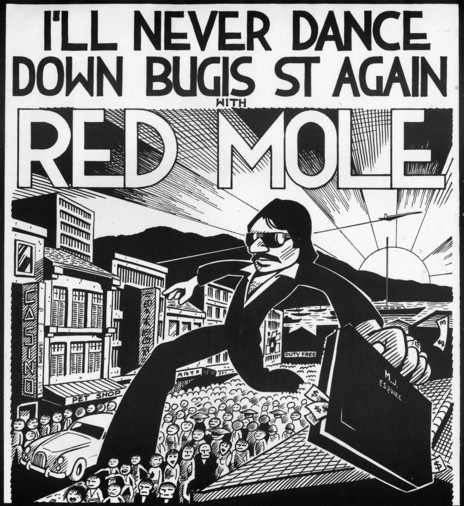

Music was indispensable for Alan. He used incidental music and song to create atmosphere, to assist narratives, to intensify or relax theatrical threads and to generate cooperative commentary. The band he used rather like a chorus in Ancient Greek theatre, and he wrote songs with musicians, keeping a sharp eye on their style, drawing maximum mileage out of their aptitude for his messages, humour and disturbing happenings.

HE USED A BAND RATHER LIKE A CHORUS IN ANCIENT GREEK THEATRE

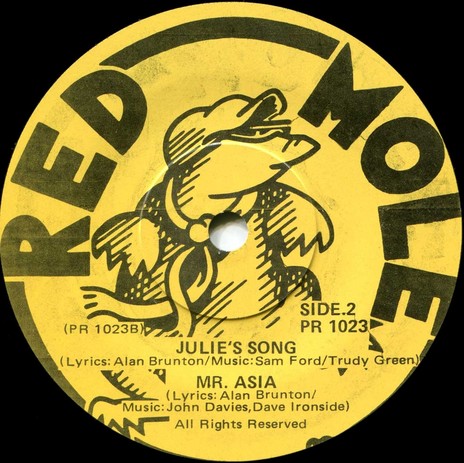

Sam Ford recounts that during a 1980 tour with The Neighbours Alan would come to him with a lyric and ask for an accompaniment in a particular style for that very night. A lyric about Taieri Plains needed a reggae backing, so Ford “weeded” the lyrics, choosing phrases that would fit into the format, and performed the song the following night with Trudi Green, David Weinstein (guitar) and Phil Steel (drums). They played in huts and halls from towns to cities on a 13-week tour from April to June, with material often shifting and alternating in this way from night to night.

Another fruitful collaboration was between Alan and fellow Red Mole actor John Davies. According to Richard Kennedy (of Mole accompanists Red Alert and later The Drongos) they wrote songs together “in a troubadour style”; one song which still haunts him was called ‘Ancient Lights’. Ford and Green provided incidental music for his poetry performances and rants, as did numerous other musicians such as Midge Marsden, Beaver, Malcolm McNeill and Kennedy. In a 2018 email to me, Kennedy says of Alan: “While he had no real musical skills, he was pretty good at indicating mood and tempo, and that was usually enough to go on. My main memories of collaboration with Alan are of providing background for him to rap/recite over.”

By 2002, it appears, Alan – at least in his collaboration with Henderson – had developed something resembling a methodology. Their last show played in the Wellington Fringe, Norway, Amsterdam and New York. It was during this tour that he died, of a heart attack. Other musicians could be name-checked over the years: Jean McAllister and Tony McMaster (members of The Drongos with Kennedy), Stuart Porter, Paul Galasso, Peter Scholes. If there is a unifying feature to the various collaborations, it is the sheer diversity of genres that Alan explored. While Alan was usually the one giving musicians a prod, Jeff Henderson was one of the few to give him a prod, towards Zarathustra Said (2002). According to Henderson, Alan’s approach had evolved into finalising his texts after rehearsal with Sally Rodwell – his partner in Red Mole, and life – and only then presenting them to the musician/composer. At that point the three worked on setting the text to music, after which Henderson drew other musicians in.

CARMEN’S NIGHTSPOT IN WELLINGTON WAS FREQUENTED BY A MIX OF SAILORS AND STUDENTS

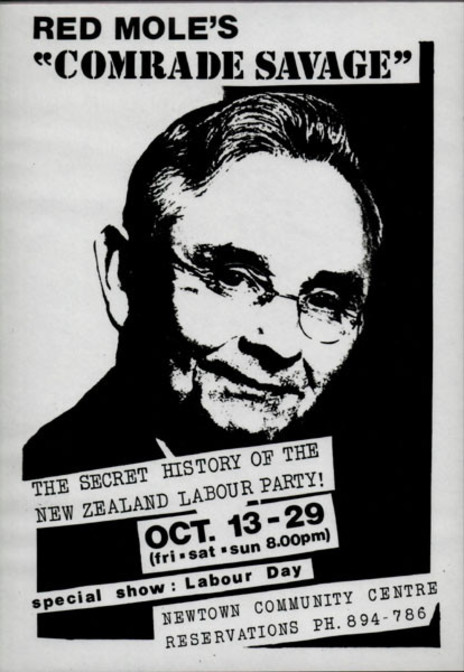

When Alan came to me in 1990, he was seeking something like a Salvation Army hymn approach for his lyrics about Michael Joseph Savage, Labour prime minister from 1935-1940. His idea was to imbue a batch of songs with that mixture of hope for freedom from poverty and near-religious fervour that Savage inspired in survivors of the Great Depression of the 1930s. Michelle Scullion and I did our best to supply the generic stuff he was looking for, and Comrade Savage played to entranced audiences in such venues as the Newtown Community Centre, and the Old BNZ Building in Wellington.

Especially memorable was when the production entered the heart of parliament itself, with a performance in the Legislative Council Chamber on the 50th anniversary of Savage’s death. On that occasion I had the pleasant surprise of being introduced to a beaming David Lange. Alan and Sally’s ability to mix and match genres with humour and irony was not lost upon Lange. No resumé of any aspect of Alan’s achievements can ignore his wife. Sally was a brilliant coordinator and choreographer, inseparable from the Red Mole “brand”, who devoted her life to Alan and the various theatre groups.

Where the song-making was concerned, Alan saw the potential for the expertise of his musicians, turning it to his own purposes, which were usually satirical and political. And because his aims were subversive of existing, divisive parliamentary and social institutions, he was especially open to contributions from his co-workers: he did not wish to become a dictator within his own milieu.

Many musicians were just waiting for a new suggestion, and grateful to turn their skills in a new direction. Others were happy for their riffs and jams to be sampled and put to good use; some enjoyed a more active part in the structuring of Alan’s scripts. Inevitably, he ended up being the guiding force of the poetry and music side, but Kennedy recalls how receptive he was to any input from the musicians themselves.

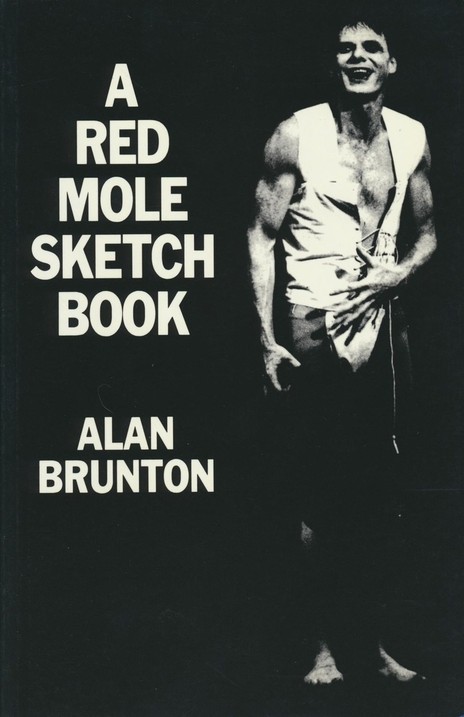

Brunton described his role as “Minister of Propaganda for the Revolution”

Speaking in 2000 to Chris Bourke, Alan described his role in a curiously parliamentary way: “Minister of Propaganda for the Revolution was maybe in some ways how I saw my role … Whatever the revolution was … Commissioner of the Enlightenment.”

There was some lack of clarity about exactly what he and Sally were trying to achieve, apart from prodding people into seeing the hypocrisy and contradictions of existent media and organisations, and I believe that if they had crystallised their exciting-but-vague “guerrilla” agenda into a clear manifesto of intention they would have lost some of their collaborators.

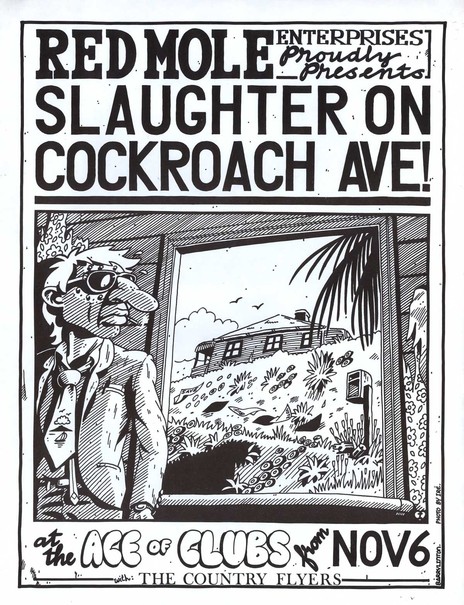

One might say that their theatre was an ongoing revolution that hoped it might never need to form a post-revolutionary government! From Brunton’s early days with French writer Alfred Jarry’s Ubu plays to the last Red Mole performances, he was “anti”. His theatre group was in the vanguard, and that could really mean anti-anything, ahead of everything. They threatened, they amused, they dared, they shocked, they converted existing genres to new uses. They turned existing conventions – above all, musical ones – on their heads, while working the small venues and the large ones, opening up minds from Bluff to Cape Reinga.

If the communist revolution was foundering upon totalitarianism, if the drug revolution was soon to founder upon directionless damage, Alan touched the greatest potential for change, intelligent music-loving young people, “expanding” their minds with hallucinogenic, thought-provoking music-theatre. And in doing that he satisfied his own inner desire to simply be a performer, a music-theatrician, a subversive dramaturg without underlined aims.

Two years before his death in 2002 he told Bourke about a sparsely attended meeting in 1968: “This revolutionary cell … would change imagination. … It was the perfect cover for anything you wanted to do because all you wanted to put on was an event, a celebration, something like that; that was what you wanted to do.”

No wonder he was such a successful collaborator with musicians. If I had a dollar for every time I have heard a musician say “all I want to do is to make music” I would be a rich man. Provocative music-theatre for its own sake is just what Alan continued to make for the rest of his all-too-short life.

--

Read: Hey Bird – Alan Brunton on rock’n’roll Christchurch.

AudioCulture publishes this tribute to Alan Brunton (1946-2002) to introduce the first publication of Hey Bird, an essay he wrote on rock’n’roll Christchurch. Thanks to his literary executors for permission.