AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

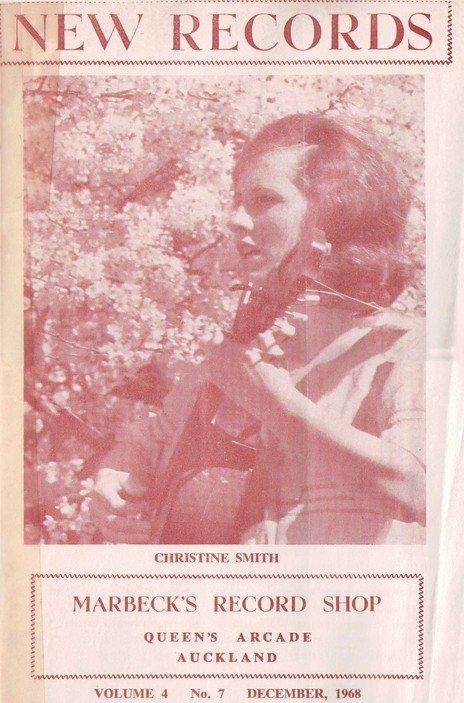

Christine Smith

It attracted the cool and the weird, the long-haired, the bare-footed, the ones who seemed to be ahead of the loop in all things political and artistic.

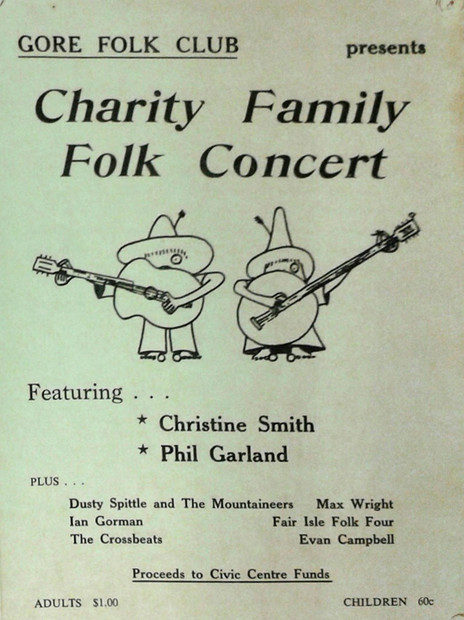

In Dunedin, where I was, a folk concert – invariably with a handful of visiting artists from Christchurch – was such a big event on campus that a mere preview would fill a full page in the student newspaper Critic. The reviews could be even bigger. The University Union Hall would be packed in a way that 20 years later only hugely popular bands like The Exponents would pack it. Before music got louder and longer, before albums replaced singles, when students could drift from one faculty to another with scant success and still be a student, folk music ruled with Bob Dylan its king. Below him a raft of instant Dylans, many called Tim or Tom, and there was always a Joan Baez.

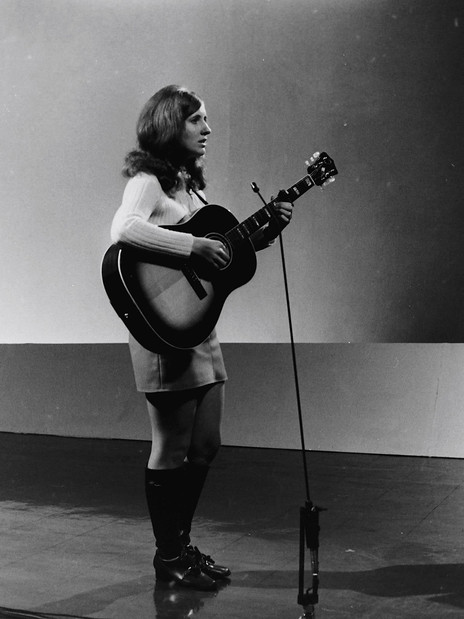

Christine Smith was Christchurch’s Joan Baez, and after frequent folk club and full concert visits to Dunedin, she became our Joan Baez as well. Baez albums littered every student flat, and whenever she appeared Smith could be relied on to deliver the many classic folk ballads and Dylan songs found on those records, influencing a long line of aspiring younger folk singers just beginning to understand their first guitar.

Smith’s first guitar – a present for her 16th birthday – was a Yamaha G50. Later there would be a Hagstrom, an Ovation and two Martin D28s, but before the Yamaha there had already been a lot of music in her life. The Smith family enjoyed music and Christine, the youngest, remembers the excitement of opening new 78s brought home from Lalolis, the haberdashery in Roxburgh, Central Otago.

“We lived in multicultural Roxburgh Hydro between 1952 and 1955 when dam-builders came from all over the world. We were exposed to Tyrolean as well as European, Middle Eastern and home-grown genres. Songs used to tumble through my being, like Strauss’s ‘Radetzky March’, ‘Doggie in the Window’, ‘Mockingbird Hill’ and ‘If I Were a Blackbird’. I listened to The Weavers with ‘Goodnight, Irene’ and ‘On Top of Old Smokey’. Dad’s friends would stand in front of the coal range and – with their backs to the warmth – they would give proud renditions of ‘The Mountains of Mourne’ and ‘Danny Boy’ with the brogue of a true Irish diaspora. My mother bought us The Littlest Angel and The Snow Goose and we would all be enthralled and appalled at the gravity of war and Dunkirk, the hunchback and Frith.”

Having mastered a plastic harmonica and wrestled briefly with a ukulele, Christine moved to the piano, which she could barely reach, tapping out tunes in tune before she could walk or talk. Her eldest sister was already learning the piano at Villa Maria College in Christchurch and Christine would stand outside listening and then reproduce every note by ear afterwards. However, formal instruction proved futile.

“When I was 10 my mother took me to Sister Michael at Villa Maria, and she tried her best, but for two terms I resisted every correct fingering and polite John Thompson tutorial until she gave up. All I remember from her is the smell of the oil heater and bruised knuckles. So, I guess you could say I am self-taught.”

Christine had made her first appearance on a raised stage four years before, playing Lena in Jan, of Windmill Land at Prebbleton School near Christchurch. While clearly not averse to a stage, she was far less fond of talent quests and competition. However in 1964, aged 16, and feeling invincible with her new guitar, she entered a Ryder-Cheshire Home fundraiser talent quest, and won the solo section, singing Ed McCurdy’s ‘The Strangest Dream’. “It was a song I loved and had a concern for the insanity that was brewing in Indochine.”

aged 16, feeling invincible with her new guitar, she entered a talent quest, and won.

So there were many influences already shaping Christine Smith. But folk music was becoming more and more pervasive. “I had been scared witless as a child when the Reds under the Bed and the McCarthy era permeated our waking and sleeping. Vietnam was an extension [of that] and a very real threat to the sanctity of life. I didn’t know what to do. When I looked around me I was bruised by the insanity of it all. With the Cold War, Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy and Castro and posturing, my early teen years were spent between raspberry-picking and the threat of nuclear war. I had never been one to jiggle and jive. I’m quite used to an endless cartoon – ever-present and alive – in my head, but the frivolity and downright silliness of what was being thrown at teens and what they were expected to listen to didn’t interest me particularly.

“I thought Buddy Holly and Roy Orbison were the best. Johnny Horton and Cliff Richard gave my sister and I songs which were infinitely singable. I was a fan of The Beatles, but the first record I ever bought was Mel Torme’s ‘Cast Your Fate To The Wind’. The first concert my Mother took me to was Black Nativity with Mahalia Jackson and Madeline Bell. I began listening to the Child ballads and the collection was inspiring. My favourite was number 78, ‘The Unquiet Grave’, and the stillness and purity of it was heart-breaking. Sing Out magazine contained compositions by Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton, Richie Havens, Len Chandler, the songs of the Appalachians and the blues, with Big Bill Broonzy, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Sister Rosetta Tharpe. These were extraordinary examples of both traditional and contemporary inspiration with Pete Seeger, Lead Belly and the songs of the dustbowl. I learned from a vibrant living history through the pages of that magazine.”

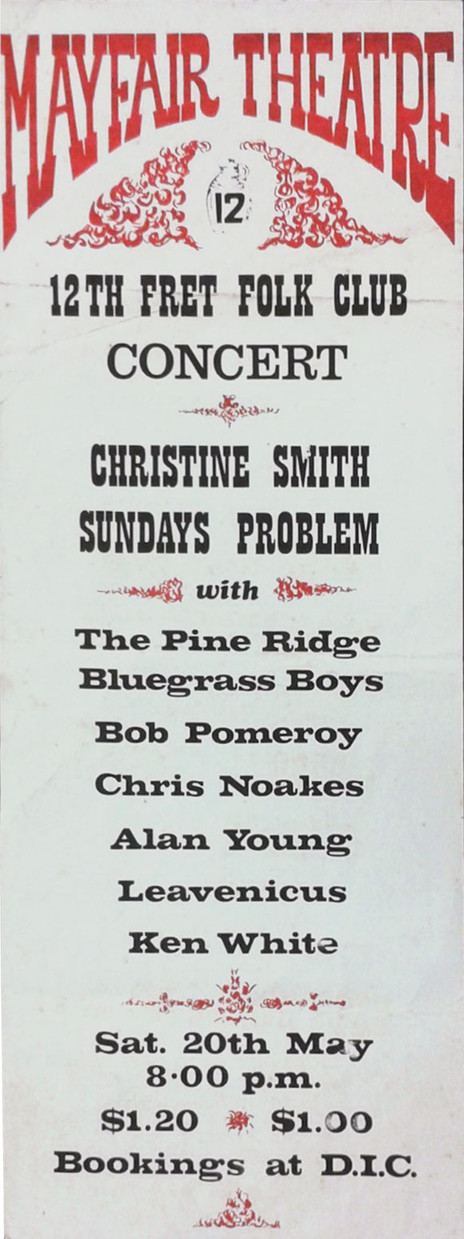

Smith quickly became a leading figure on the Christchurch folk scene. There were many fine musicians and plenty of venues: Canterbury University, The Plainsman, High Street and Bedford Row, and, on Sundays, the Stage Door after the legendary Chants R&B had played the Friday and Saturday (the Chants often came along to listen to the folk music on Sundays).

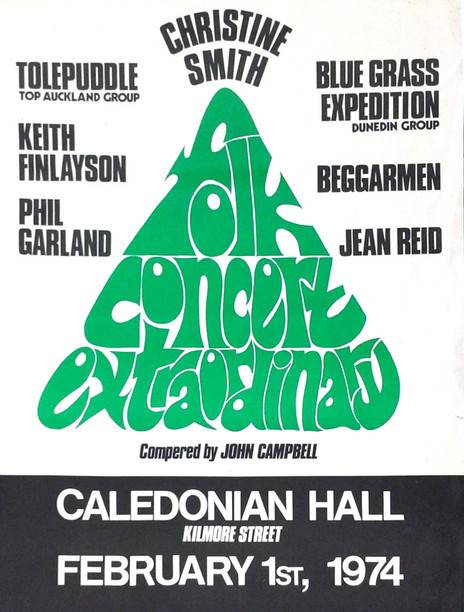

“I travelled up and down the country, from New Year celebrations at Mount Maunganui with The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, and the Hunter brothers – who were just forming their new group, Dragon – through to the AMP Shows in Invercargill with Lew Pryme. I toured the country and was welcomed onto a marae in Ngāruawāhia. There was hardly a fortnight in between engagements before I would be travelling.”

Visits to Dunedin with Christchurch’s finest – Garland, The Band of Hope Jug Band, et al – were always treasured. “I felt most at home in Dunedin. It had been a city close to my childhood and I felt welcome there. I remember performing [Dylan’s] ‘Daddy You Been On My Mind’ at a concert in the Town Hall which flew, and it was an extraordinary feeling that night having the entire audience singing Brahms’ ‘Lullaby’ with me, in German. Dunedin audiences in Filleul Street understood the interweaving of stories in sets and seemed, on an intellectual level, to comprehend nuances. They were more attuned to the history of Otago with the gold fields and settlers.”

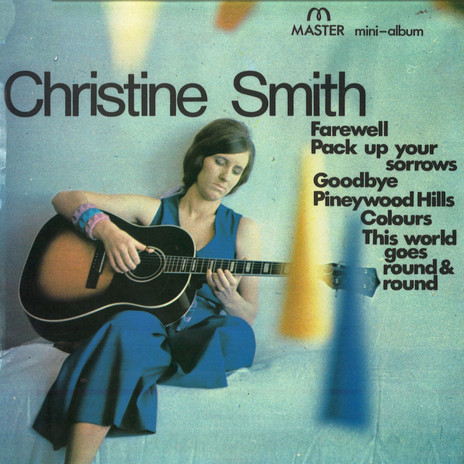

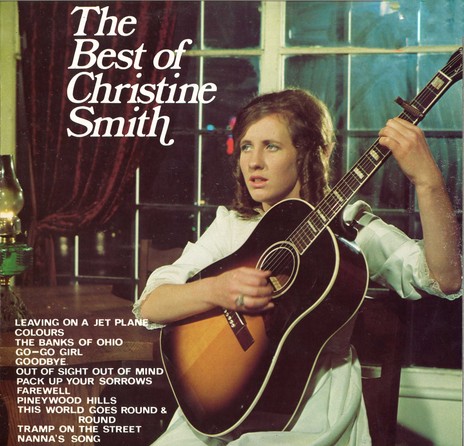

The South Island were poor cousins of the north back then when it came to making records, but Hoghton Hughes signed Smith to his burgeoning Master label in Christchurch, where she recorded ‘Leaving On A Jet Plane’ (in one take), ‘Banks Of The Ohio’, ‘Go-Go Girl’, ‘Tramp On The Street’, ‘Out Of Sight, Out Of Mind’ and an album, The Best of Christine Smith. ‘Out Of Sight, Out Of Mind’ – a beautiful Dave Jordan song – remains a career highlight. In 1969 it won Jordan the Silver Scroll for Best New Zealand Song; he had also won the year before with ‘I Shall Take My Leave’.

Playdate magazine reported that Smith was due in Auckland in May 1969. “She was unfortunate enough to have a release of ‘Leavin’ On a Jet Plane’ at the same time as it was issued by Shane, and unfortunately it couldn’t compete, but she is someone to watch.”

Smith sees herself as “an interpreter of song”, although she wrote her first piece of music at five.

In 1971 Smith was signed by Philips and recorded the album Lady for them, later re-released as Country Lady. In 2015 it was digitised and reissued by Universal.

Christine Smith sees herself essentially as “an interpreter of song”, although she wrote her first piece of music at five (‘Frogs Frolic’), and wrote music for schools. (She often set students’ poems to music, and, most notably, shaped Janet Smith’s Cook Bicentennial-winning song ‘Land Ahoy (Aotearoa)’, which won an award for Cook’s bicentennial in 1969. But she has been happy to leave writing to other composers she admires, especially New Zealanders.

Smith became a fixture on music television with residencies on the NZBC’s highly successful The Country Touch (hosted by Tex Morton), Country Road, Christchurch’s Ah Dee Doo Ah Dee Doo Dah Day and Popco, and Dunedin’s Country Folk (with John Grenell). She supported many overseas artists, including Don McLean, Pentangle, Shelley Berman, Mike and Alice Seeger, Jerry Lee Lewis, The Bee Gees, Kamahl and Patrick O’Hagan. Musically and technically, The Pentangle shows remain memorable for her. Their master guitarist Bert Jansch said he loved her right hand, and Bee Gee Robin Gibb told her she sang his ‘First Of May’ the way he had imagined it should be sung. She almost toured Scandinavia and Europe with Pentangle, but like so many “nearlies” in music, it didn’t happen.

There were other industry mishaps too. Smith represented herself when negotiating to appear on The Country Touch. A few years later, booking agents who had represented artists on the programme refused to pay her when she was the support act for some international musicians – because the agents assumed they had missed out on their cut for her Country Touch appearances. In 1980 she decided to leave the music industry for good. “When creativity and business continue to collide a decision has to be made. I left the industry because I needed to feed creative processes, not fight mercenary interests.

“My exit from the industry which I loved was deliberate. There had been far too many acts of ungenerous and confusing parsimony and artists were being played one against the other. It was difficult enough to make any kind of living. I held three jobs at any one time in order to try to support myself. Fortunately, I had a mother who had been there for me through all of the joys and difficulties.

“In 1979, our eldest son was born, and as a final exit, I recorded Billy Joel’s ‘Honesty’ for Stars On Sunday. With Daniel in a backpack as I recorded the final guitar track, I waived any further participation in order to experience a far more nourishing existence.”

Since then, Smith, ever the seeker, has been involved in a wide range of projects. For most of the 1980s she worked in Queensland as a musical specialist for state and Catholic education departments. She returned to Christchurch in 1993 and completed a double major in political science and sociology, then taught at Canterbury University and CPIT. From 2006 to 2013 she was employed in Qatar, selected from 126 international applicants, preparing the country’s young nationals for higher education.

“I am a firm believer in seeking a state of grace and knowing it is perfect while my life is not.”

“I have spent my life peering around corners and I don’t really feel obliged to leave that behind just yet. Retirement hit me on the chin, as being expected to become invisible is really not my style. I am a firm believer in seeking a state of grace and knowing it is perfect while my life is not. I am currently researching and am surrounded by libraries which hold what I require.”

Is there a bucket list still? “My head is never far from silence and sound,” says Smith. “There are projects at hand and I feel it would be refreshing to collaborate with fresh musicians who will bring a new slant to what I do and I am always open to integrating jins and ajnas* from the sounds I have heard while overseas.

“A bucket list?” She laughs. “Not to kick it just yet!”

Smith lives in Melbourne. Her three children, Daniel, Phoebe and James, are successfully established professionally in London, Amsterdam and New York. “They all share my passion for music, although their careers have channelled creativities of a different nature."

--

* Pitches that form Arabic melodic modes.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air