He was still drawn to music and mimed guitar on a tennis racket, while watching ABBA on television. As a young child who wanted to play music, his mother thought his hands were too small for guitar so instead he started piano lessons at age eight and then a few years later studied classical guitar. He bought his first electric guitar from Harmony House in central Auckland in his early teens and found that he could add distortion to its sound by putting it through the family stereo and overdriving it.

Van de Geer convinced a school friend to learn bass so they could perform, though unsurprisingly a cover of ‘Twenty-four Hours’ by Joy Division didn’t go down that well during a lunchtime performance at Avondale College. They came second at a school rockquest with a cover of ‘Spellbound’ by Siouxsie and the Banshees – fortunately the judge Annie Crummer knew the song and could appreciate it.

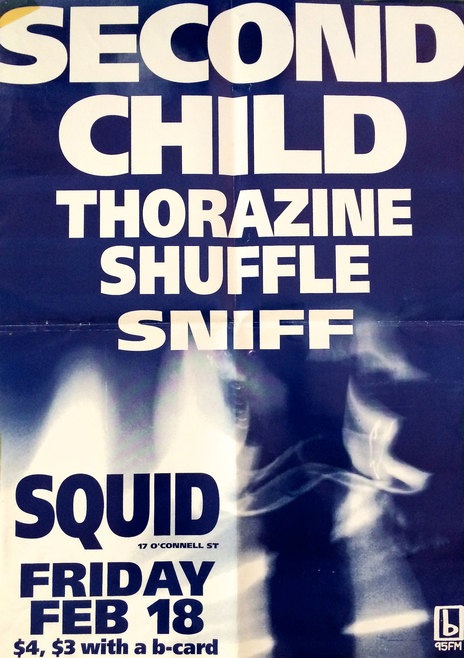

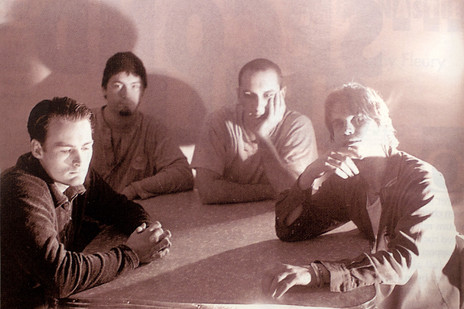

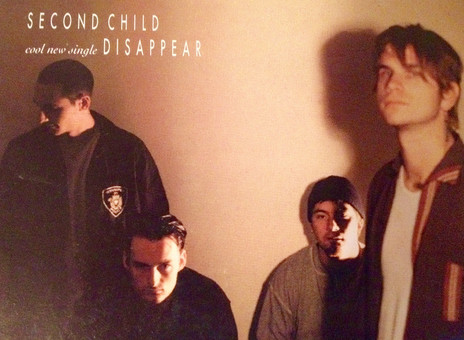

Second Child formed soon after – the pair found drummer Luke Casey through an ad on a music store noticeboard and then added Casey’s schoolmate Damien Binder on vocals, allowing Van de Geer to step away from the microphone and focus solely on guitar.

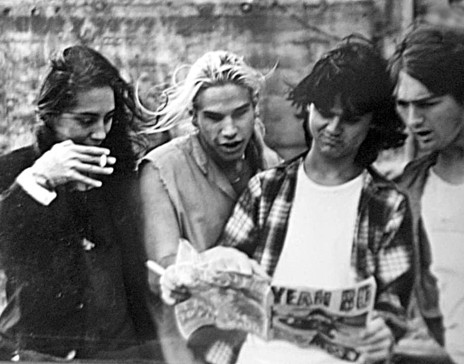

Second Child and The Lab

The most groundbreaking guitarists of the era had moved away from the bluesy riffing and chugging chords of the 70s, instead using pedals and effects to create new sounds. Van de Geer was drawn to the more textural sound of Geordie Walker (Killing Joke), Bernard Sumner (New Order), The Edge (U2), and Will Sergeant (Echo and the Bunnymen).

Recording at Progressive Studios, Van de Geer found the studio environment enticing

After a few experiments on a friend’s four-track, they booked Progressive Studios where Van de Geer found the studio environment enticing. “I had a small mixer and a drum machine at home, but it was amazing to see a full mixing console with all the outboard gear and tech around the place, then watch the process of the instruments being mic’d up and having the recording come together, then being mixed. It just looked like an incredibly cool thing to do.”

Second Child recorded more demos at student radio station bFM with Matthew Heine (S.P.U.D.), before finally saving up money for time at professional studio The Lab Recording Studio (again with Heine). To help fund it, Binder sold his cricket gear and Van de Geer sold his Tube Screamer guitar pedal. Second Child were managed by Rip It Up writer Kirk Gee, who convinced Murray Cammick to sign them to his Wildside label and this led to the release of mini-album, Magnet (1991). Their alt, post-punk rock was complex, with unusual rhythmic patterns and often obscure song structures, but their live shows were powerful and they played support slots with Nirvana, Fugazi, and The Jesus & Mary Chain.

Van de Geer had originally studied for a year as a quantity surveyor before quitting to pursue music, and instead undertook the year-and-a-half course at the newly opened School of Audio Engineering (SAE). His first job as a sound engineer was making ads at a radio station, though he used their studios after hours to record The Nixons (later known as Eye TV) and short-lived grungesters Love Buzz, as well as demos for Second Child.

Van de Geer had dated Coralie Martin and when her band The Malchicks went into The Lab with Mark Tierney, they asked him along to assist, hoping his similar musical interests might help guide the sessions. The Lab was owned by Bill Lattimer whose music instrument shop Bungalow Bill’s was on Symonds Street, with the studio tucked behind it. Van de Geer had previously tried door- knocking at local studios and, after spending further time in The Lab, Lattimer finally took him on as one of the studio’s in-house engineers.

Van de Geer was behind the desk at The Lab while some incredible tracks were laid down, including ‘Come Back’ by Garageland and ‘Drive’ by Bic Runga. There were plenty of noisier sessions too, with punk-influenced bands like The Warners, Balance, and Muckhole. He also got to work with his old friend Luke Casey when Eye TV came to The Lab to record their album Birdy-O (winning him best engineer at that year’s 95bFM awards). Van de Geer was also nominated for Best Engineer at the 1997 NZ Music Awards for his work on the 1996 Strawpeople album Vicarious. He credits The Lab as being the perfect place to develop his skills.

“When I first got there the Lab had a 16-track Fostex, then about a year after I arrived they got a 24-track Otari, which was game changing. We were also running Soundscape which was a PC-based digital recording system, so I used that in a real basic way to sync additional tracks with the tape machine. People in the scene knew me because of Second Child, so they assumed I’d be able to make great guitar records. Fortunately I had the trust of a whole scene of people who wanted me to engineer and produce their projects.

“In The American alt scene ... big live drum sounds had come back into fashion”

“The American alt scene was led by bands like Dinosaur Jr. and Nirvana so big live drum sounds had come back into fashion, after the era of drums being very produced and processed in the 80s. The Lab’s recording room sounded fairly dead, as it wasn’t a massive hard-surfaced room, so I had to work a bit harder to get a natural reverb sound. I loved the chance to work on some incredible music, with great people. That was a time when making records often meant being ensconced with an act, living in each other’s pockets for two to three weeks doing 14-hour days and trying to create something cool in an intense time period. Then that particular act would move on and as the engineer and producer you’d jump onto the next project and do it all again.”

Meanwhile, Second Child were driving their heavy alternative rock sound into a more accessible direction, as heard on ‘Crumble’ which begins with a heavy, rhythmic verse riff before opening into a melody-driven chorus. Van de Geer used downtime at The Lab to record and mix their album Slinky (1996), which received support from music video television and from the newly arrived Channel Z radio station. Yet after earlier years of b-Net [student radio network] support they found themselves in an awkward middle ground: too mainstream for student radio, but not mainstream enough for the commercial stations.

Van de Geer became intensely busy with studio work and at one point found himself mixing an album in the studio while the rest of the band rehearsed in the building next door. He felt like his ability and focus to continue with Second Child had run its course, so he and Binder decided that Second Child would come to an end. Van de Geer used his Dutch ancestry to get his EU passport with the plan of heading to the UK and Europe to further his studio career, but instead he took up a new musical project that kept him down under.

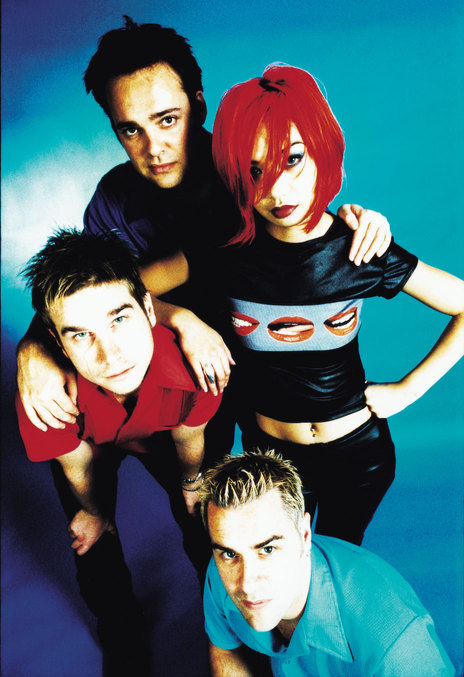

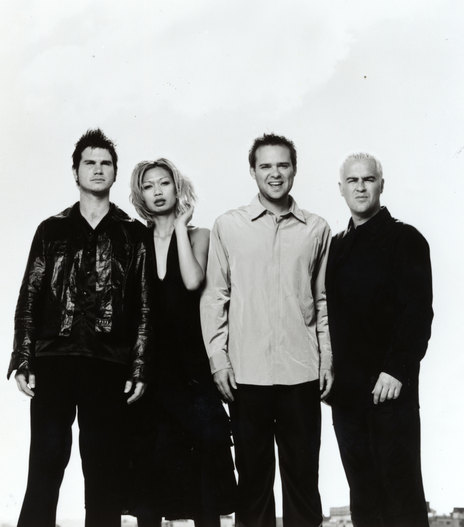

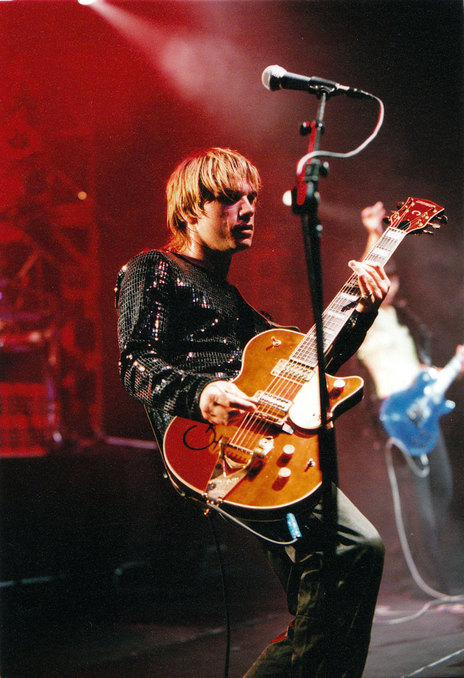

Stellar*

Over the years, Chris van de Geer had often rubbed shoulders with the three other members of Stellar* – Boh Runga, Andrew Maclaren, and Kurt Shanks. Second Child had played gigs with Stellar* and Van de Geer had recorded their single ‘Happy Gun’ during a brief patch when their guitarist was Riqi Harawira (ex-Dead Flowers). Before Second Child broke up Stellar* had asked him to join, but due to his commitment to his own band he had declined, though he now was keen and able to take up the offer.

Stellar* was all “ready for a change ... get beyond the whole alt-guitar, post-grunge era.”

“We were all ready for a change in sound to get beyond the whole alt-guitar and post-grunge era. When they were younger, Boh and Andrew had been in a covers band doing 80s pop and so Andrew was comfortable using Midi technology and playing drums to a click. We started working with Luke Tomes, who was a great Pro Tools engineer and could program beats alongside Andrew, so we started experimenting with warping the sounds or cutting and pasting sections. We had incorporated this approach into the demos that Sony eventually signed us from.”

Sony’s new head of A&R Malcolm Black arranged an initial recording budget of $60,000 and suggested they work with Tom Bailey who had relocated to New Zealand from England a few years earlier. Bailey’s career included plenty of his own hits in the Thompson Twins and he had produced acts such as Debbie Harry and Jerry Harrison. The band worked with Bailey and Tomes to refine every individual musical element, which meant Van de Geer adjusted his guitar lines to suit.

“A keyboard line or loop might be filling the space where guitar chords might otherwise be, so I’d add something more sparse or a simpler line. There’s that cliché of using the studio as an instrument, but that’s really what we were doing. We were always creating new sounds and trying to take things to the extreme. I’d be asking myself – ‘how do I mess this sound up or make it sound less like a guitar?’ On ‘Part Of Me’ for instance, I used a Cry Baby wah pedal as a filter to give it that choked sound then put the recorded guitar sound through a lo-fi tube plug-in within Pro Tools, then added delay and panned it across from left to right speaker. That way it ended up working more like a filtered synth part.”

Elsewhere on the song the guitar went in other directions, with textural delay parts, a plucked arpeggio part and also a reverb-heavy lick in the chorus added by Tom Bailey. This in-depth working process meant some songs went through multiple versions, most notably ‘Violent’ which went all the way to disco and back before it found its final form. Van de Geer created the guitar sound for the chorus by plugging a Very Metal distortion pedal directly into a Mackie desk (a low budget project studio mixer at the time), creating a fuzzy distortion that was hardly what he would usually consider a good guitar tone but worked perfectly in this instance.

Mix (1999) reset expectations for how world-class a local rock band could sound and also the level of success they could achieve within Aotearoa, with the album reaching No.1 and selling over 80,000 copies (pushing past The Feelers’ Supersystem from the year before). It also swept the NZ Music Awards, winning Album of the Year, Best Engineer (Luke Tomes), Best Producer (Tom Bailey and Stellar*), Best Songwriter, Single of the Year (‘Violent’), Top Group and Top Female Vocalist. The hype around the band was massive; Van de Geer felt that it was lucky they had already been in the music industry for a decade and were experienced enough to remain level-headed about what was happening.

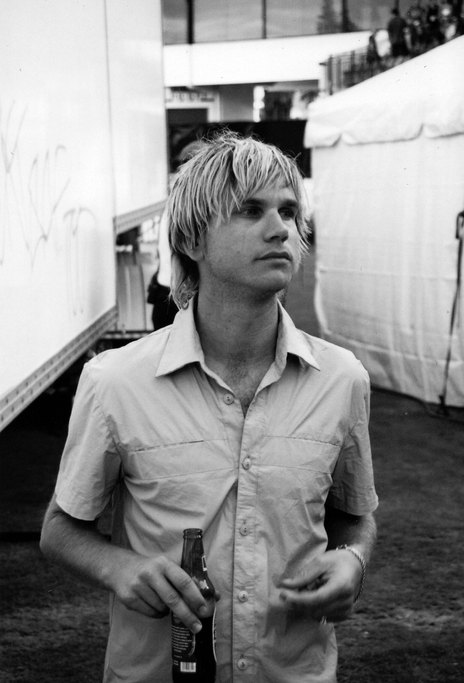

The experience of Stellar* in Australia was both enjoyable and fraught

After an initial tour of Australia supporting Alanis Morrisette and Garbage, their label Sony wanted them to take on Australia next, which Van de Geer found both an enjoyable and fraught endeavour.

“On the day we arrived in Sydney, the marketing and the product managers who’d put together our whole plan of attack were both made redundant. We spent a lot of time up at the Sony offices but we didn’t have a key person working the project. We still did a huge amount of interviews and television performances. We had an apartment in Coogee, Sydney, and a house in the suburbs of Melbourne. Then we’d just go back and forth between the two cities every week playing shows, doing the 10-hour drive along the Hume highway. After a while we took turns flying, but it was a grind at times and we didn’t break through as we’d hoped. We felt that Sony Australia probably went with the wrong single initially by pushing ‘Every Girl’ instead of ‘Violent’.”

They also played in Germany where there was a lot of interest from Sony’s affiliate labels and they did a sold out show in London before returning home to start work on their follow-up album, Magic Line (2001). Van de Geer now believes in retrospect that it would’ve been a good time to take a break, but instead they were only part way through recording before a national tour was booked to promote its release, which created a fast looming deadline and added a lot of pressure for the completion of the album. Some of the mixing took place in LA at Ocean Way Studios with legendary mix engineer Jack Joseph Puig and then remaining tracks were mixed last minute back in New Zealand. Magic Line also went to No.1 and sold platinum, with the band sounding as strong as ever on tracks such as ‘Taken’ and ‘All It Takes’, but Van de Geer could sense the sometimes unrealistic expectations coming from outside the group.

“Mix had been such a huge success which obviously made it hard to top. The thought from our management and our label was that we could and would blow up internationally. Previously, post the Mix release, there were definitely certain opportunities that weren’t taken which may well have helped us break overseas but at the time the decision was made to wait for what was thought to be a more opportune moment. Then by the time we released Magic Line, it was a month after 9-11. Our manager Campbell Smith was over in the States with the record and the feedback he got was – ‘everything is in disarray, the labels aren’t spending money on any new acts at the moment’. There was basically no chance of us getting traction in the States at the time. A lot of things in the music industry always come down to timing and circumstances.”

Van de Geer got back into engineering, including working with Dave Dobbyn and Tim Finn

Between albums, Van de Geer got back into studio engineering work. This included recording tracks for Dave Dobbyn’s Hopetown (2000) and working on the Tim Finn album Feeding The Gods (2001). The latter already had a US producer on board which meant Van de Geer could just focus on getting good sounds and enjoy the engineering work rather than also having to drive the creative process. Then after Magic Line he and Stellar* drummer Andrew Maclaren worked on a few projects together, including Carly Binding.

“Andrew and I had made some demos with her. Then when she signed her deal with Festival Mushroom Records, we were brought on as the production team with Andrew handling programming and me engineering duties. Carly was writing on acoustic guitar, so the songs were quite raw. We didn’t want to take the same approach as Stellar*, but did want to incorporate some technology to give the songs more texture and avoid it being a straight acoustic record.

Binding had just left the reality show band TrueBliss, so she had to break any negative preconceptions the public might have of her as a legitimate solo act. However she laid all doubts to rest with two strongly written Top 10 hits (‘Alright With Me’ and ‘We Kissed’) and the album Passenger (2003) was similarly successful. This led to Van de Geer winning Music Engineer of the Year at the NZ Music Awards (he and Maclaren were also nominated for Producer of the Year).

By this time, Stellar* had settled into a more relaxed approach for the recording of their third album, Something Like Strangers (2006).

“We did a lot of the recording at Luke Tomes’ studio then finished it off at my home studio, before mixing at York Street Studios. We did a tour to support that, then had another break before we did the ‘So Alive’ single as a new addition to the Best Of album in 2010.”

The upside of Stellar* becoming less busy was that Van de Geer could get back into the studio while finding a new way to take his career forward.

Bigpop

In a music scene as small as Auckland, it wasn’t surprising that Chris van de Geer and Joost Langeveld had come in contact over the years. Van de Geer had seen Langeveld’s bands NRA and Nemesis Dub Systems, with the latter being signed to Wildside at the same time as Second Child. He met him through mutual friends Paul Casserly (Strawpeople) and Greg Johnson, who Second Child vocalist Damien Binder was living with at the time. Langeveld and Van de Geer had both worked on Strawpeople albums in the past, but finally crossed paths on Count Backwards From Ten (2004), with Van de Geer providing guitar, engineering and production and Langeveld working on some of the tracks as a programmer and producer.

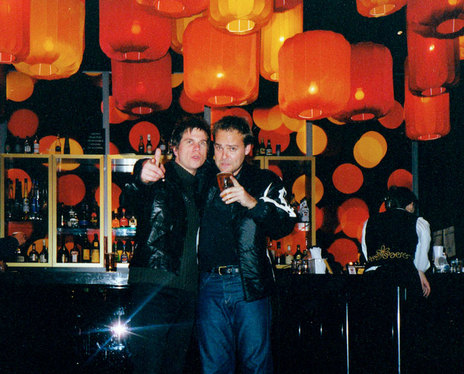

Joost Langeveld and Chris Van de Geer began working together as “Bigpop”

They became friends and decided to start working together on some more commercially based music and audio projects. Langeveld and Van de Geer eventually decided their projects together needed a formal business name and so around 2005 they began doing work as Bigpop – an amalgamation of “big bang” and “pop art”. The core of their business was producing music for an international fitness brand, composing music for advertisements and TV shows, including the theme for Police Ten 7. Their business grew to a point where they hired their first official studio space in Anzac Ave in 2008, before moving to Halsey Street near Victoria Park in 2010. Over that time, they also began to employ a number of staff and moved into other areas such as audio post-production.

Van de Geer continued engineering and producing young bands and artists. His work on Parlour Games (2006) by energetic four-piece Revolver saw him win Sound Engineer of the Year for a second time, though unfortunately the band had arrived a little too late to take full advantage of the retro-rock revival. Often he was brought in by rock bands who were aiming for crossover success, such as Solstate and These Four Walls. However, he gradually veered towards doing mostly mixing work which he could do from his home studio. So it had been a while away from having a “full immersion” in the studio when he went into York Street Recording Studios with Black River Drive to produce their debut album, Perfect Flaws (2010).

Van de Geer mixed Kurt Shanks’ solo album Blood Line Heart (2012). Shanks then started a new project with Lani Purkis (Elemeno P, Foamy Ed) called Delete Delete. Van de Geer added guitar and mixed the debut single – the punchy synth rock/pop punk ‘What Do You Take Me For’. This led to him joining the band, which saw him return to playing live shows and recording, as the trio released a number of singles.

By 2015, Bigpop had become more established and their commercial workflow was well under control so Van de Geer and Langeveld decided to launch their own record label and publishing company, which runs alongside their production business.

“It was a way to pass on what we’ve learned to younger musicians who needed some assistance in finishing and releasing their material. Consequently, we ended up doing A&R work – developing artists and supporting them on their musical journey. Our input can be anything from helping on the production or mix, through to guiding them through the process of figuring out who they are as artists. It’s been a fairly intuitive and organic process moving into the business side of the industry – which very often needs to tap into the same creative thinking side that you use for music creation and production. With the label and publishing entities we’ve purposefully focused on building a support system and community for artists – especially those that might not otherwise have a home or outlet for their music.”

“we’ve purposefully focused on building a support system and community for artists”

Some of their earliest signings were guitarist Arli Liberman, whose instrumentals led to work on film scores and indie folk act This Pale Fire. They also signed one of their Bigpop engineer/producers Maude Morris (daughter of legendary producer and Th’ Dudes guitarist Ian Morris and When The Cats Away’s Kim Willoughby) and her sister Julia’s indie synth pop band LEXXA (Julia soon went solo as Jupita). Van de Geer enjoys the chance to tap into this work when time allows.

“It can sometimes be hard to have enough time to cover off the different aspects of things I’m working on, but having the label and publishing companies means that I can tap into our artists’ projects at different stages throughout the creative process and offer some mixing or production thoughts. I can totally satisfy my ‘studio fix’, despite not being hands-on with engineering and production aspects on a full-time basis anymore. Sometimes it can just be a matter of getting an artist and producer to relook at something or push the boundaries a bit more. When someone is deep in a project, they can get lost in it, so it’s always nice to come in with fresh ears.”

One of the label’s earliest breakthroughs was with the alt hip hop act CHAII, whose songs were not only streaming hits but were also synched for massive advertising campaigns by Apple and Fendi, as well as appearing in the PlayStation game Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater.

“For about three-and-a-half years, we also had another studio running out of the old Kog Studios in Kingsland. CHAII came in there to do some demos and we started to discuss helping her to put out music. She is very much self-produced, along with her partner Frank, though I did end up mixing a few of the CHAII tracks. Mostly it was just a matter of offering some production advice when it was needed and supporting her on her own journey.”

Since then, Bigpop Records has continued to work with varied artists, including the hip hop/pop crossover duo of Haz & Miloux, pop artist Cecily, ragga toaster Jujulipps, indie synth pop artist Isla Noon and alt goth act Proteins of Magic, amongst others. Strawpeople have also featured on the label, with Van de Geer and Langeveld working as their co-producers on Knucklebones (2023), which led to Van de Geer playing guitar for the Strawpeople’s live performances.

Stellar* have also returned to the live stage in recent years. The band first reformed to play a reworked cover version of ‘Maxine’ in honour of Sharon O’Neill for the 2017 NZ Music Awards, which was then followed by a run of festival appearances. Van de Geer enjoyed the chance to perform with old friends and was able to get a firsthand sense of how much their music still means to fans, without the stress that sometimes went with shows and band business during their initial run. He has even been able to make things easier for himself by reducing his large analogue pedalboard down to a set of digital presets, so that he no longer has to tap-dance between pedal settings as he previously did.

His studio work has covered a period of huge change: from working on large-format mixing consoles and recording to tape in Second Child; to running digital software synched to tape for Stellar*, through to working fully digitally “in the box” and he has found that digital modelling of sought-after analogue gear and virtual instruments can sound as good as the real thing.

“I’ve been very fortunate to have a career in the music industry for 30 years (and counting). It’s been quite mind blowing. As a teenager experiencing that excitement of writing my first songs in a garage, I never had any idea where music would lead me. But being able to diversify and experience all sides of the industry from being an artist, working as an engineer/producer through to the business side has kept it incredibly interesting, creative and enjoyable. I think the best underlying factor outside of the work itself though, has been the amazing experiences I’ve had and the community and relationships that form throughout the process of creating music with others.”