AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Tom Bailey

aka International Observer

Away from the pressure-pot climate of London and adrift in a comparative backwater, Bailey could finally address his artistic concerns, free from the demands of agents, lawyers and contractual obligations. What resulted was of immense benefit to our local industry, and to Bailey’s own muse.

Backtrack to September 1996, when I opened the doors of Beautiful Music, a tiny experimental record store above a Malaysian restaurant in Auckland’s Ponsonby Rd. My joy was to stock all manner of weird music in a pleasant lounge environment where people could sip freshly made espresso coffee.

One of my first regular customers was a 40-something chap who began turning up every day for a flat white and a long chat about music, the universe, anything under the sun. We were already fast friends when one day my 1980s-obsessed assistant turned up and began acting strangely. When my coffee-drinking conversationalist had gone on his merry way, my assistant, with a look of utter disbelief, said, “DO YOU KNOW WHO THAT IS?” I replied that he was just some nice chap called Tom who had been coming in every day for a coffee and a chat. “IT’S TOM BAILEY! FROM THE THOMPSON TWINS”, exclaimed my gobsmacked, star-struck assistant.

Unwilling to be defined by fleeting pop success, Tom Bailey wanted an escape valve to enable the exploration of other key interests.

Of course, this revelation meant nothing to me, because the Thompson Twins hadn’t even caused a blip on my radar. During the group’s heyday, when they scored big with hits like ‘Lies’, ‘Love On Your Side’, ‘Doctor Doctor’ and the perennial smoocher ‘Hold Me Now’, I was exploring the outer reaches of industrial rock, dub and experimentalism. It hardly registered that Tom Bailey and his New Zealand-born, Mt Roskill-raised partner, Alannah Currie, had in 1984 become the biggest act in America, or that in 1985, they had performed to bazillions in the giant Live Aid fundraiser. Why should I care?

Ironically, this was the foundation on which my friendship with Tom was built. Seeking refuge from the impossible glare of celebrity, Bailey had opted out of the madness, so he was only too happy to rub shoulders with people who lived in parallel musical universes to the scene he had been immersed in the UK. Unwilling to be defined by fleeting pop success, Tom Bailey wanted an escape valve to enable the exploration of other key interests.

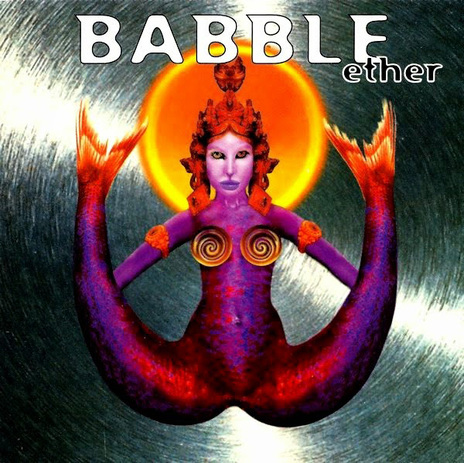

Tom Bailey had moved to Matakana north of Auckland in 1995, with Currie and their two children. There, they recorded Ether, the second album of their post-Thompson Twins project Babble, making it a Kiwi project.

Finding the Matakana location too remote, they then moved to Freemans Bay, just off Ponsonby Rd, where Tom’s gentle induction into the local scene began. But at the start, he admits that he was “running away” from the industry.

“We’ve retired from the biz, now let’s do some of those things we’ve always wanted to do but success never allowed us to do,” he says. “Because there was never time, there were always managers and agents pushing you towards the next money making opportunity. And I guess that was part of our plan to live here, to make sure that we became artists again and not just commercial machines. And that was difficult, and some of it worked and some of it didn’t, but it was all fun.”

One of Tom’s first musical moves in NZ was to delve into his love of dub with International Observer.

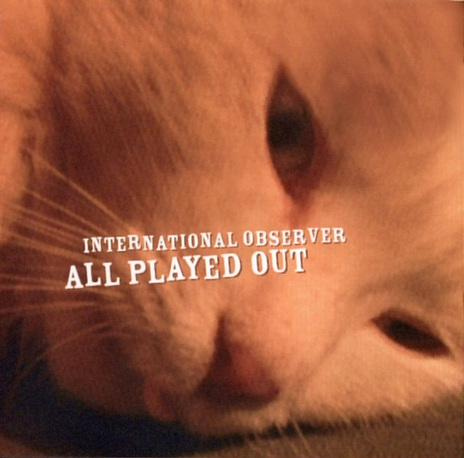

Shrugging off the glossy synth-pop of the Thompson Twins, and the hi-tech electronic dance moves of Babble, one of Tom’s first musical moves in NZ was to delve into his love of dub with International Observer. Initially teaming up with Rakai Karaitiana, Bailey performed many low-key performances, most of them free and to tiny audiences, and most of them in the Queen City, culminating in the still astonishing Seen album in 2001.

Influenced by the German dub-glitch electronica that was seeping out of Germany in the late 1990s, Tom added his own melodic gifts and compositional skills to the pot to create an electronic sound that was distinctive and at times, staggeringly gorgeous. And it’s still one of the best-sounding albums to have come out of NZ: I use it to review hi-fi gear, even now.

“It was absolutely an artistic experiment,” says Tom. “It was fun and I felt that I had permission to do that which was always denied me in London. It just all came flooding out. I don’t think I would ever have done it [in the UK], because it would just have been too hard. You can see in Babble it was the beginnings of that. There were instrumental dubby sounding tracks in Babble that showed what I wanted to be doing, but we weren’t quite able to go the full distance, we were still trying to be a song-oriented group. And we were still recovering from the audacity of actually killing the Thompson Twins and wondering if we’d gotten away with it.

"Because the business of that was pretty weird. We were still signed to a major label. We were going to change our name and change everything that we do, we were going to be unrecognisable, and Warner Brothers at that point, because they were still famous for the old-school trust that major labels paid lip service to at least, trust in the artist, said ‘whatever you want to do is fine by us’, you know. There must have been some horrible sinking feelings in business meetings.

"And of course Babble could never have done as well as the Thompson Twins, but it was a desperate thing. We had to get away from making hits, and give the artist part of us more space in the process, in order to survive in any form. We just got tired of writing 3:57 second pop songs. So I think the Observer in a way is just the natural continuation of that progression away from Top Of The Pops, and this repressed desire to do things that you weren’t allowed to do. Suddenly, I felt the freedom, and some weird cultural permission to do it here that I didn’t feel back in London.”

In the early incarnation of the Thompson Twins, they lived in a squat in South London, where “dub was the music of the neighbourhood – it was the music we all played and that came out of every window that you walked past.

“I was caught up in the mystique of the studio as well, and I really liked the idea that some kind of magic took place that was nothing to do with singing a song or projecting to an audience but just took place in the room where you were. And not everyone appreciated that but it was a really precious thing.”

His projects in NZ included Indo-fusion group Holiwater and the duo Kolab, as well as production work for local artists, notably Stellar*.

Interestingly, Bailey neither drinks nor takes drugs – surely unheard of for a practitioner of the black art of dub! And no doubt it partially explains his focused approach to a multiplicity of artistic endeavours: outside of music, he’s an accomplished painter, while his projects in NZ included Indo-fusion group Holiwater and the duo Kolab, as well as production work for local artists, notably Stellar*.

It was his production and arranging work on the first, best, and most successful Stellar* album, Mix, where his keyboard skills were also on display, that got Bailey back for a brief moment into pop mode.

Tom had met Paul Ellis and his successor at Sony, Malcolm Black, and it turned out that Boh Runga and Andrew McLaren, Stellar*’s drummer, were Thompson Twins fans.

“I’d done a couple of remixes for Bic Runga and it was all very friendly and casual. I decided to take them seriously, and thought it deserved the respect of saying ‘I’m going to treat this exactly like I’d treat an existing successful band’, to see how that would work. In other words if it was worth doing, if I have some kind of international perspective, then I should apply it to this. And that’s what happened. I think it got out of control, it got too tough and aggressive or something, this need for success.

“But they should be remembered for their good work. I love the kind of slow and more mysterious songs on that first album, rather than the attention-grabbing ones.

“I enjoyed having a rolling dialogue, and the fun of a band making its first record, and I enjoyed contributing to it. A little bit of guidance, a little bit of advice, but more of just amping it up, helping it to feel exciting. I think I’m more of a musician than a producer, I think I end up wanting to play on things too. It’s like I joined the band. You do get excited. You do get a thrill playing with people.

“But the more they grew in confidence that they could achieve some kind of international success the less charming the music became. The second one they took to LA and had a mix by some team of maniacs, to have the super-competitive radio-sounding edge, but it just sounded like a bunch of razor blades to me. Steve Lillywhite once gave me some great advice: make a record that you want to turn up, not one that you want to turn down. And it seemed to me that you wanted to turn up the first record, and turn down the second.”

But really, it was Tom’s presence on the scene at a crucial moment of growing pains that made a difference. He loved to provoke discussion, and it was the conversation that Tom provoked amongst notables in the NZ music industry that made us stretch our limbs and morph a little. People often talk about musical brilliance, but seldom about the ability to inspire, and that’s what Tom did, wherever he participated.

“I was living here so I was integrating, and that makes it different, but I think also I never therefore had to deal with the problem of how to preserve the authentic voice of New Zealand, which is a difficult issue, and I had a natural get out of jail card for that, which was that I wasn’t from here but I was living here, and I just brought all my baggage with me and said ‘okay, this may be of interest simply because I have a different perspective’. And to a certain extent I was outspoken about that, and it got me into trouble a few times. I used to moan and groan about the same old same old approach to music that I saw being employed on a local level. So as well as having not to feel guilty about that New Zealand voice I also didn’t have to give it that much respect. It was a bit like having an access all areas card to the local scene without really having the responsibility for it.”

A networker without guile, Tom knew everyone, but was never a name-dropper. And while he knew many of the record company heads and the charting acts, when it came to his own artistic endeavours, he was resolutely underground.

International Observer, for instance, usually performed for free, or at fundraisers for the likes of GE-Free NZ or SAFE, and its debut album, Seen, was at first distributed almost entirely from my store, although it was later properly issued through UK label Different Drummer. Kolab, his ambient collaboration with English conceptualist Simon Redfern, never performed but made two albums that nobody knows about.

“Kolab had two albums, and both are available on the Internet, as creative commons works. So, anyone can have them and they can even use them for things without our permission.

"We gigged a few times in Europe, did a gig for the Syd Barrett Appreciation Society (laughs). I was introduced to a gaggle of elderly ladies who all claimed to be Syd Barrett’s girlfriends. It was a ‘happening’, a recreation of those happenings that early Floyd would have been involved in.”

"There was nothing we liked more than finding some cheesy country and western record and converting it into a Kolab texture."

– Tom Bailey

Kolab is about as experimental as Bailey’s music gets.

“We discovered one day how to take nano-fragments of pre-existing music, found objects, usually of the most repellant sort, so there was nothing we liked more than finding some cheesy country and western record and converting it into a Kolab texture. And that was just such a moment of inspiration for us both that we just thought ‘let’s do this’.”

Another obscure project from Tom’s time here was the Sussex Quartet: “Three pianists, myself, Simon and a German man whose man I can’t remember. There were only three – that was the joke! It was the genesis of the Thompson Twins name.” Sadly, though there were many rehearsals/private performances, no recordings exist of the “quartet”.

A similarly low-key but better documented project is the ongoing Holiwater Group, an Indo-fusion aggregation featuring Tom on keyboards/electronics, Vikash Maharaj (sarod), Prabhash Maharaj (tabla) and James Pinker (percussion). Vikash and Prabhash are a father-son duo from Varanasi, India, who come from a line of master musicians going back more than 500 years, while Pinker is a former member of The Features, Fetus Productions, SPK and Dead Can Dance.

Despite the quality of the musicians, Holiwater also often performs at low-key venues. I was proud to host them at Beautiful Music, when it had shifted to a site adjacent to Artspace on Auckland’s K Rd, and in February 2014, they performed just two gigs: Leigh Sawmill, and at TV presenter/chef’s Bharat Jamnadas’ Arch Hill home for a select 40-or-so fans. I was one of them. They stopped their performance to sing me ‘Happy Birthday’. I just about died.

Tom tells me that playing to 40,000 people in a stadium is not necessarily any better than playing to 40 people in a lounge.

“It’s on so many levels satisfactory to do that kind of thing. The only thing of course is that you can’t make a living out of it. I do these little labour of love projects, which never make any money but I enjoy them. And personally and artistically they’re very satisfying, but I’m essentially living off my Thompson Twins royalties, and so thank God for that. If it hadn’t have been for that, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity [to do this], and I saw that very clearly, that success brings opportunity and you should make use of it, and it’s not just to go further along the same trajectory all the time.”

Perhaps the union that is Holiwater says a lot about the way Bailey works: hatched in NZ, the groups is nevertheless international and has subsequently played in all sorts of contexts on the world’s stages, including of course, WOMAD.

“We actually met in New Zealand, in my house in Freemans Bay, so there’s a strong connection with New Zealand for Holiwater.

“It’s very positive thinking, and that’s the personalities of the group members. It is a self-confessed east meets west project, a cultural fusion, so we don’t have to pretend to be anything that we’re not. We don’t use all those weird, challenging rhythms, but one of the pieces that we do is really foreign to Western ears. I like to have that, because it’s like introducing a pungent spice into a meal. Try this – OOOH! If that was all you gave them they’d run away screaming and pinching their nose. But it’s nice to have it as part of the mix. And incredibly exciting for me, too, because you could never, ever make a Western pop record using that. It’s just too weird. But it’s great, because it’s by default admitting that we don’t know everything, that everything we know is only a belief system, there’s always something outside of that that would refresh you, if you care to take it.”

He still regularly returns to catch up with friends and to perform with both Holiwater and International Observer.

Tom Bailey returned to the UK in 2005, but his influence here lingers, and he still spends part of his year in NZ, where he performs and creates music with others. Although it’s probably less likely that he’ll tour his latest American show down under, “the Thompson Twins’ Tom Bailey” in a lineup featuring other 1980s heroes, Midge Ure and Howard Jones.

Retrospectively, Tom says of the NZ music scene:

“New Zealand has a particular difficult set of circumstances because of the isolation, but also its habit of cultural borrowing. For example, the number of hip-hop groups here who think that they have a natural right to make it in America and then find that there’s 10,000 groups like them not making it. Why should they be given a chance?

“It’s a kind of sad fact that 99 times out of 100 it’s not going to be successful in the way that people fantasise it could be, so you have to really define what success is and localise it. Generally speaking the things that have translated tend to be the ones that are more generic. They fit the commercial necessities of a globalised generic market. The things with real character and spunk are always going to be limited by the localism.”

As for his own place in the musical universe, Tom says he’s happy to be a dabbler:

“I can’t be exclusively International Observer anymore than I can be exclusively Thompson Twins. And I actually believe that being a dabbler like this, being a jack of all trades and a master of none, you end up informing every area that you work with, everything you do, so when you play with the Holiwater band, some of the melodic content comes from having written pop songs, some of the overall sound scape comes from International Observer, and when I walk onstage in America [on the "Thompson Twins" tour] I’ll be subconsciously dragging the Holiwater band with me. I’ve even snuck in some Indian arrangements.”

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air