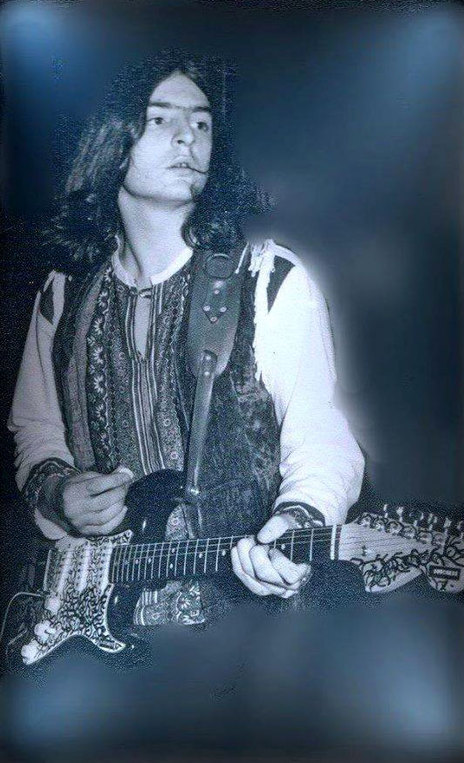

18-year-old Stanton was a man on a mission in late 1973. He’d played in Auckland garage bands in his mid-teens but decided he had to change his whole approach upon hearing the era’s guitar heroes Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page.

From the end of 1970 to the end of 1971, Stanton stuck to a routine of rising in the morning, having a cup of coffee and a slice of toast and playing guitar on his bed for eight hours, seven days a week for the entire year. Believing he was now at a standard to start gigging he formed Duchess, Battle of the Bands winners in 1972.

By the end of the next year, Stanton was in a band called Transformer but was intent on starting a group that performed only their own songs and bypassed the regular pub work for concerts. Any jam situation he was in he would be eyeing up the other players as to whether they would fit his new plan.

Inspired by the music of Billy Cobham, Chick Corea and The Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Birds Of Fire, they began experimenting with time signatures.

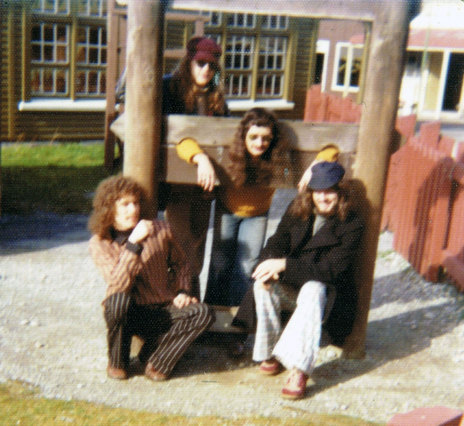

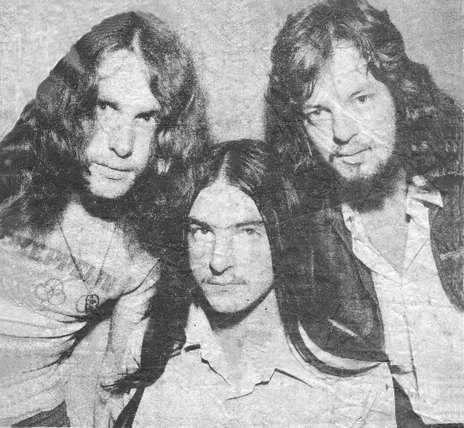

When Hamilton band Judge Hoffman played some Auckland dates for club owner Johnny Tabla, Transformer were playing next door and the two line-ups checked each other out. Judge Hoffman were on their last legs and Stanton and their drummer Neville Jess swapped numbers. Before long, Jess moved north and the two began putting songs together.

It became obvious they needed a bass player as creative and ambitious as they were and Jess put in a call to his Judge Hoffman bandmate Allan Badger, at a loose end in Rotorua. Badger’s unique bass lines were exactly what Stanton was looking for and soon the three men were living in a house in Wanganui Avenue, Ponsonby, writing and rehearsing their own repertoire.

Inspired by the music of Billy Cobham, Chick Corea and The Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Birds Of Fire, they began experimenting with time signatures. A keen mathematician, Stanton worked out that if one of them played in 3/4 time, one in 4/4 and one in 5/4 that every 60th beat they would all be on beat one of their respective time signature!

Stanton christened the trio Think because that’s what he wanted their “fairly esoteric” music to make people do. But their first club gigs for Johnny Tabla only served to alienate the audience with unheard of songs like ‘Conan The Spider’ and ‘Mantis’.

In the provinces it was a different story. One of their early out-of-town successes came in Napier. Father Time were resident at the legendary Cabana and their singer Steve Grant called Badger to tell him the Ahuriri Tavern, another pub in the city, was looking to put bands on and he’d suggested Think. Father Time even took the night off from the Cabana and brought their crowd to the Ahuriri to make a good impression.

On another trip down country, Think’s hire van broke down behind Hamilton near a field with a procession of huge electricity pylons. The band rolled a joint and to Jess the towers began to take on the guise of big ladies with wide, welcoming arms. Stanton produced his guitar and by the time a replacement vehicle arrived the trio had written ‘Big Ladies’.

Having established a cult following in the upper North Island, Think demoed ‘Light Title’, ‘Our Children (Think About)’ and ‘Mantis’ at Bruce Barton’s Mascot Studio, as much to listen to how they sounded as to attract any record company interest. At this point they began discussing bringing in an organ player.

There was also another chance to make their mark in Auckland as guests of Maurice Greer’s Human Instinct at the opening of the Greer brothers’ new Shanty Town club. Think’s powerful take on progressive rock totally enthralled Human Instinct guitarist Phil Whitehead.

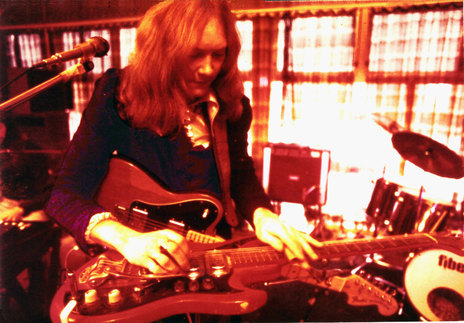

Born in England, Whitehead had toured New Zealand with Beam (aka Beam Unity) and then The Movement, backing pop singers such as Craig Scott, Eliza Keil, Maria Dallas, Suzanne Lynch and Bunny Walters. After forming Father Time with Steve Grant, Whitehead was lured away to Human Instinct.

Once Frank Greer had established Whitehead could use a hammer and saw, he put him on a contract that paid $10 more than the dole whether the band were playing or not and started them to work as part of a gang building the Shanty Town nightclub under the Civic Theatre. Once it opened, Human Instinct were resident while recording their Peg Leg album, which went unreleased until 2003.

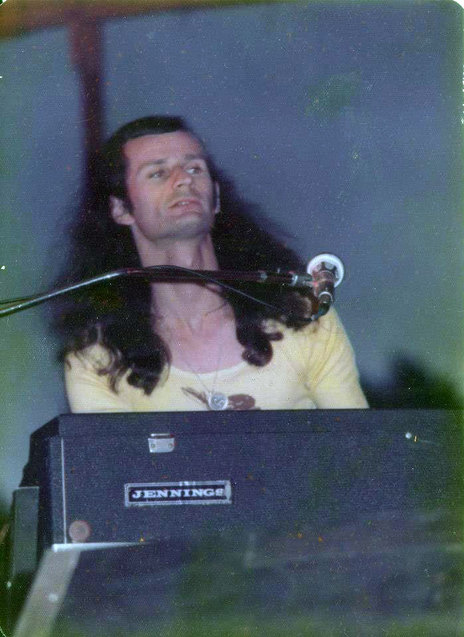

In early 1975, Maurice Greer was talking about building another nightclub and Whitehead took his leave. Allan Badger proposed Whitehead come and jam with Think with a view to joining as second lead guitarist, and Whitehead suggested he bring along his organist mate Don Mills, who had been sitting in with Human Instinct.

Whitehead and Mills had been tight since their days in Beam and, although Whitehead had left the band, Mills had remained with them until March 1975 when guitarist Harry Lyon handed in his notice, telling Mills he was forming a band called Hello Sailor with a couple of friends.

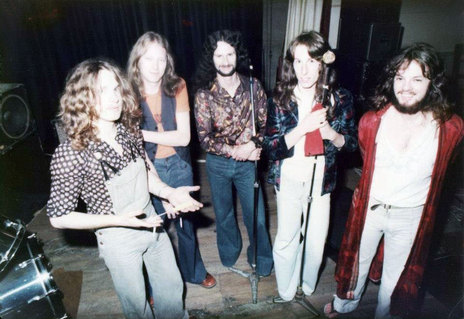

It turned out Kevin Stanton and Neville Jess weren’t privy to Badger’s invitation to Whitehead to join Think, let alone his including Don Mills, but the five-piece did endure a few tense rehearsals and possibly even a gig before the shit hit the fan and Stanton was gone amid accusations both ways of going commercial, calling secret meetings and issuing ultimatums.

Feeling mightily ripped off, Stanton retreated to lick his wounds and eventually formed Brigade with drummer Paul Dunningham. He spent 1976 writing the bulk of material that would make up the first two albums for his later band Mi-Sex, who would conquer the Australian pop charts as the 1970s clicked into the 1980s.

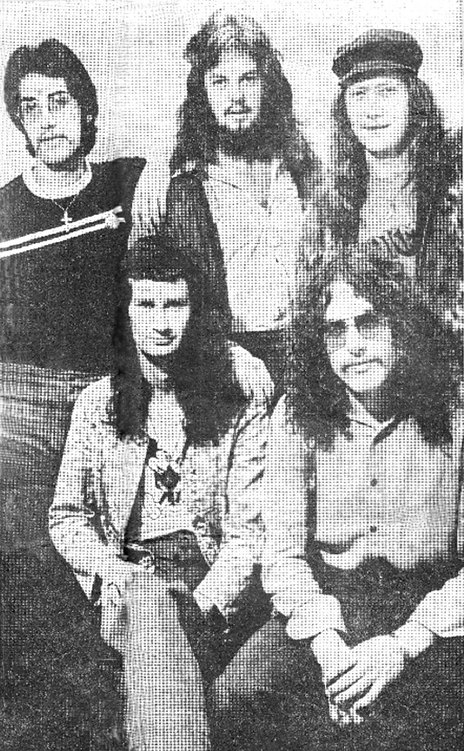

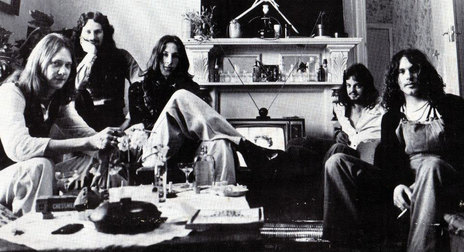

The new four-piece Think knuckled down to arranging the material they had for guitar and organ and continued writing new songs. When in Auckland they would work three nights a week and when on the road they worked five nights a week outside of the Lion Breweries circuit.

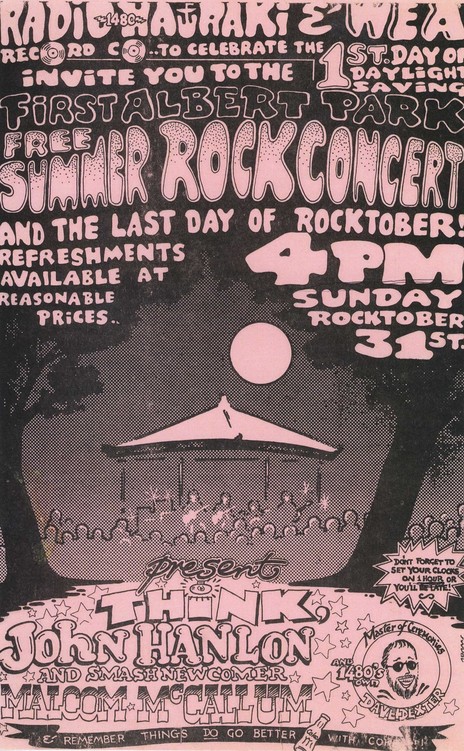

Augmenting their own songs with one side of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon, Think attracted capacity crowds at the Windsor Castle in Parnell where they also caught the attention of WEA New Zealand boss Tim Murdoch. Eager to establish the new label, he offered Think a recording deal.

After some initial assistance from promoters such as Lew Pryme, Benny Levin and Russell Clark, Don Mills and Neville Jess would sit down on a Monday and hit the phones, ringing venues throughout the country to set up six to eight weeks’ work on the road.

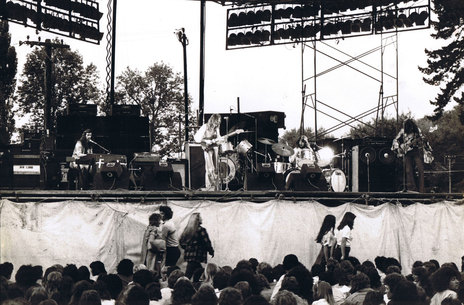

They were one of the first bands in the country to have their own full front-of-house production with Charlie Newson mixing sound and Bruce Corston on lights. A Think show was something to behold complete with pyrotechnics and recordings of atomic bombs.

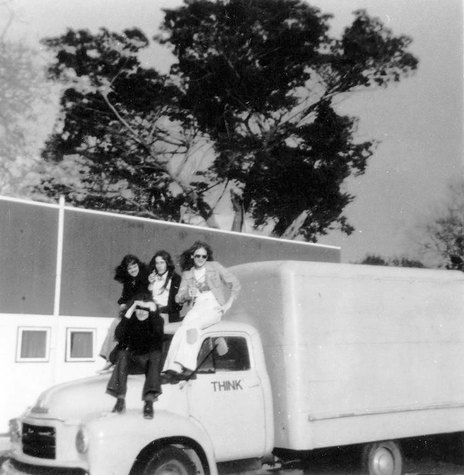

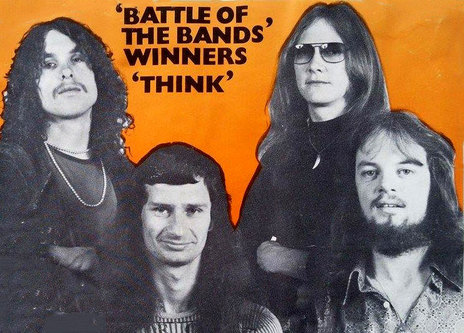

While resident at the Cabana in late 1975, Think received a telegram from Benny Levin strongly encouraging them to enter the Battle of the Bands in Auckland. Believing they might be a good chance at taking the title, they made the trip north under a tarpaulin on the back of a flat-bed truck.

On arrival at the YMCA, Allan Badger was whisked away to the kitchen by a winking Levin and asked if the band would hang around for the grand final. It later transpired that P&O Cruises, who provided the main prize of a Pacific cruise with the winners as entertainment, were annoyed that a number of previous winners had broken up before they could accept the prize up to a year later.

With their growing fan base, busy calendar and a deal with WEA, Think were just what P&O were looking for and took out the title. The runners-up were a Lew Pryme-managed outfit by the name of Footprint, who had probably broken up by the time the cruise came about.

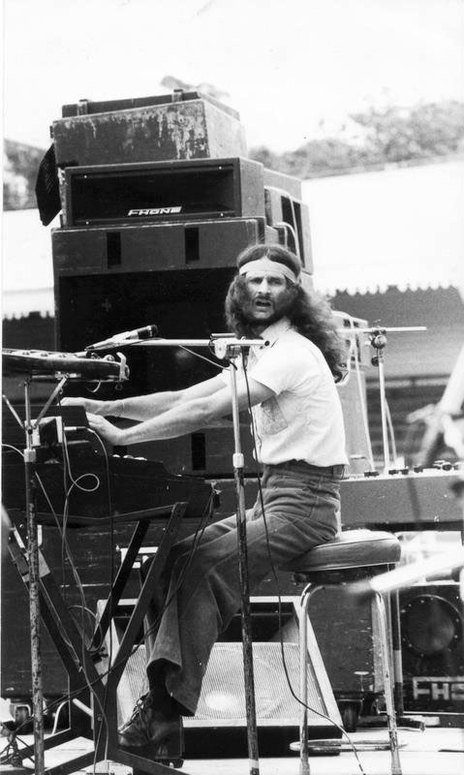

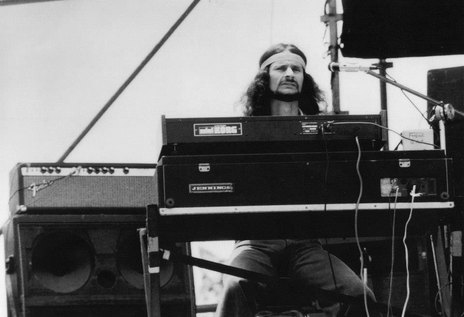

Over the next two months, Think were twice at Western Springs – opening for Deep Purple on November 13 and The Doobie Brothers on January 29. Although they didn’t meet Deep Purple, their road crew were brilliant, even providing Don Mills with some of Jon Lord’s heavy-duty valves to replace the factory ones in his Leslie speaker cabinet. The Doobies were more than happy to mix.

As the cops moved in, Mills explained that the syringes were full of lube oil for the moving horns and tonewheel in his Leslie cabinet.

Police picked on the wrong man when they raided the Heads Ball in Dunedin and zeroed in on teetotaller Mills. The rest of Think were clean but Mills’s briefcase was full of lanolin cream for his dry hands, and syringes. As the cops moved in, Mills explained that the syringes were full of lube oil for the moving horns and tonewheel in his Leslie cabinet.

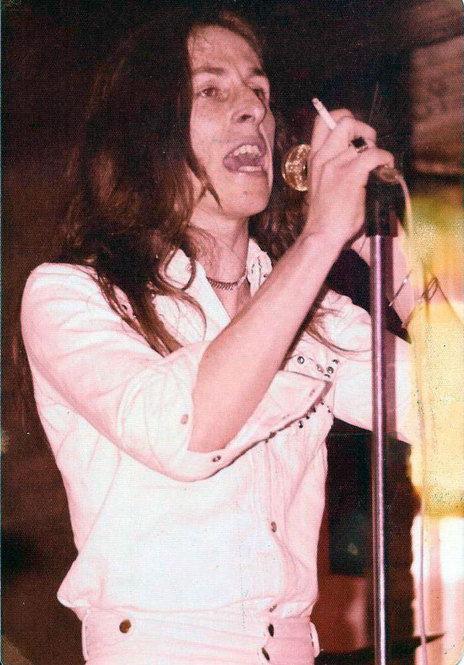

Tiring of being the band’s sole lead vocalist, Allan Badger suggested Think recruit Graffiti singer and guitarist Ritchie Pickett to ease the pressure. Badger had seen Graffiti at the Lady Hamilton over two nights and was impressed by Pickett’s singing and showmanship. They all knew each other and Pickett was quick to accept.

His inclusion wasn’t without moments of discomfort. Think were a favourite of the manager at the Aranui Hotel in Christchurch and he would wake at 3am to let them in after they’d driven their truck from the Picton ferry. But on their first appearance with Pickett they were met with, “What’s he doing here?” “He’s in the band now.” “Oh, fuck.” It turned out Graffiti had left a trail of mayhem through the area last time they had passed through. On another occasion, having devoured three quarters of a preserving jar of sherbet, Pickett was taken to the Napier Hospital “literally fizzing at the butt”.

In April 1976, WEA put Think into Stebbing Studio with blind veteran producer Julian Lee and engineer Phil Yule to record the We’ll Give You A Buzz LP. They were given a week, Monday to Friday from 8am to 5pm, with an hour for lunch, to lay down the best of their well-rehearsed, gig-tightened repertoire.

There were the group compositions ‘Light Title’ and ‘Our Children (Think About)’, both dating from the Mascot demo with Kevin Stanton, ‘Big Ladies’, ‘Rippoff’ and ‘Look What I’ve Done’ and Stanton’s own ‘Stringless Provider’.

All went well until it became apparent on the Friday that they had run out of time to revisit the lead vocals. Allan Badger and Ritchie Pickett had sung guide vocals and there were big arguments to try and get more time to complete them properly, but Lee and Tim Murdoch decided the guides would do just fine.

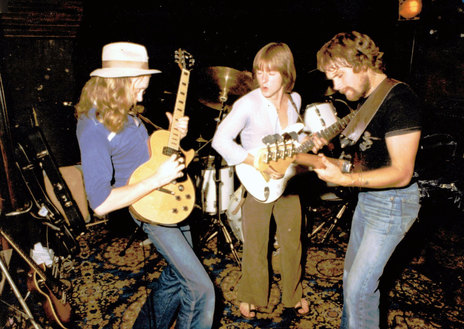

The record’s strong suit was the virtuosic interplay of guitarist Phil Whitehead and organist Don Mills. While the album was being mixed in July, Think were at the Auckland Town Hall, tuned up and ready to open for Little Feat when Feat leader Lowell George refused to let them go on.

They won TV’s Grunt Machine songwriting contest with the LP’s closing track ‘Our Children (Think About)’ before setting their sights on Australia. P&O had come through with the Pacific cruise engagement and Think had negotiated to disembark in Sydney to try their luck there. P&O were happy for the band to take up the second leg of the cruise at a later date.

Allan Badger sat in the offices of WEA New Zealand when they called WEA Australia to inform them Think had a new album out on the Atlantic label and were relocating to Sydney. The companies agreed for the band to be met and accommodation organised, and that December they set sail across the Tasman Sea, with their entire PA and lighting rig in tow.

When they arrived in Sydney, there was no one from the record company to meet them, so they organised a taxi truck and made their own way to a house they’d been given access to. When it turned out to be a dilapidated shack halfway to Wollongong and the car that went with it was immobile, they took the taxi truck straight back to Sydney.

Badger rang WEA Australia. “Oh, we heard something about you guys coming, but we didn’t realise it was today,” said the exec. “Can you get a hotel? When you do, give us your number and we’ll be in touch.”

A small advance was procured and the band went to Bondi, found cheap rooms on Campbell Parade and started looking for gigs. Their first was at a disco where they played between sets from the DJ. To make matters worse, in all the advertising they were called Fink.

Things got better when they created their own resident gig at the Bexley North Hotel. But not for long – trouble was brewing with Ritchie Pickett. He and his girlfriend were living in Kings Cross with a WEA employee charged with looking after Think, but who had more interest in Pickett’s lady.

When the rest of the band discovered Pickett and the girlfriend were experimenting with hard drugs and had got involved on the periphery of the Mr Asia scene, they decided they had to let Pickett go. They sat on Bondi Beach and drew straws – Phil Whitehead drawing the shortest and being tasked with sacking Ritchie Pickett.

Whitehead then wrote a letter to Father Time’s singing drummer Lindsay Brook asking if he would replace Pickett. The offer included a flight to Sydney with his drum kit, paid for by WEA, and the balance of the Pacific cruise, but it was the prospect of getting into original music that saw Brook come onboard.

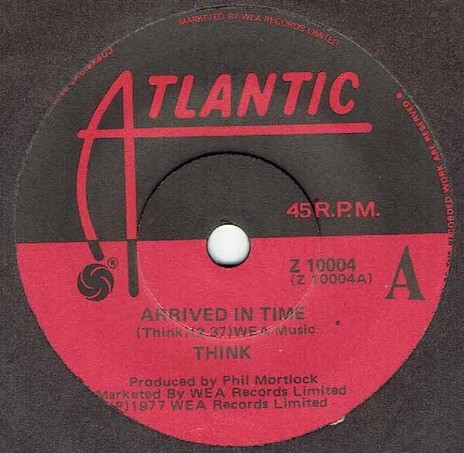

As soon as he arrived, Think started rehearsing and writing what would be their next single ‘Arrived In Time’ (produced by Phil Mortlock at EMI Studios and released on Atlantic), and the new line-up debuted at the Candy Factory in Cronulla on July 9, 1977. Eight days later, they boarded the Arcadia to take up a cruise of the Pacific Islands – the final leg of their Battle of the Bands prize.

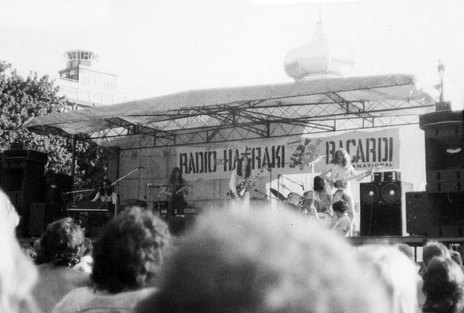

Because they boarded the boat in Sydney, the Musicians Union of Australia insisted the band be paid, and the band negotiated passage back to Sydney rather than Auckland, as was the initial deal. Before docking in Auckland, the entertainment officer rang ahead to Radio Hauraki and advertised that Think would be playing concerts on deck when the Arcadia berthed and departed. The call worked and the wharf was packed.

Their first gigs in Melbourne were as support to the likes of Renee Geyer, Cold Chisel and Dragon.

Back in Sydney, Think bought a truck with their P&O payment and headed for Melbourne. Their reasoning was that every tourist map of Australia they saw had an image of the Sydney Harbour Bridge over Sydney and an image of a musical note over Melbourne. They smashed the windscreen on the way and the trip ended up taking 24 wet and cold hours.

Their first gigs in Melbourne were as support to the likes of Renee Geyer, Cold Chisel and Dragon, and Think would set up with two drum kits on stage – Brook joining Neville Jess for a few songs with two drummers before returning out front. The practice didn’t last long before Brook concentrated on vocals and second guitar.

The support slots were helping Think’s profile, but by the time they forked out their share of PA hire and paid for their own roadie, it was costing the band $5 or $10 each more than their fee per show. Things were starting to unravel and factions began to appear, especially when Don Mills and Neville Jess suggested the band return to New Zealand to regroup.

There was a glimmer of hope when Mushroom Records boss Michael Gundinski met with the band, booked them to play his Bombay Bicycle Club venue and gave them assurances that if they stuck around into early 1978, they would be a Mushroom priority. The label had achieved massive success with Skyhooks in 1975 and had recently signed fellow New Zealanders Split Enz and Mother Goose.

But it was too little too late for a homesick Don Mills, who quit and returned to New Zealand. When he immediately scored a cabaret gig in need of a drummer in Christchurch, he rang Neville Jess and he also quit Think. For the next two years they played six nights a week behind Tom Greening at the Chateau Commodore, making more money than the venue’s assistant manager, who hated them for it.

With the interest shown by Mushroom, Lindsay Brook persuaded his former Father Time organist Alan Moon, who’d also been a mainstay of BLERTA, to fly over to join Think. English-born drummer Robbie France-Shaw, who the band had met at rehearsal rooms they used, replaced Jess.

The new line-up set about writing a bunch of new material and recorded the single ‘Hollywood Superstar’ but the song went unreleased. And after just one or two gigs, the revamped Think folded. Unsettled by outside influences, Allan Badger was fed up with their inability to gain any ground.

For the next six months to a year he jammed occasionally and went on the road with Mother Goose, helping their soundman Mike Emerson. Guitarist Phil Whitehead enrolled for a term at a Melbourne music college and Lindsay Brook returned to the drums with The Brian Baker Band.

After some time away, Badger came to the conclusion that Think had unfinished business and he got in Whitehead’s ear about re-forming. He had a contact willing to bankroll the band’s return to New Zealand where they could rehearse and get their shit together before coming back to Australia refreshed. Not unlike Mills and Jess’s proposal of the previous year.

They drafted guitarist and saxophonist Steve Lunn from the music college and drummer Mark Nash from a band Whitehead was rehearsing with and flew back to New Zealand. Ironically, Think founder Kevin Stanton and his new band Mi-Sex were flying to Sydney at about the same time. His early Think song ‘Touch My String’ would evolve into the title track of Mi-Sex’s 1979 hit album Graffiti Crimes.

Think kept some of the We’ll Give You A Buzz material and wrote a new repertoire. They hired a full-on PA rig, employed Whitehead’s brother Mike as soundman and started hitting up the old traps.

Badger and Whitehead insisted there be no drugs or drunkenness on stage, but they weren’t opposed to a hit of powdered glucose for a pre-show sugar rush. One night at a packed Hillcrest Tavern, they were running late and hadn’t partaken. When Badger retrieved the plastic bag of white powder and the band administered a spoonful each on stage, the police were called.

The band took a break and officers pounced from both sides of the stage but soon found the powder to be harmless. The audience may have enjoyed Think beginning the next set with ‘So You Think You’re A Detective’, but the police most certainly did not.

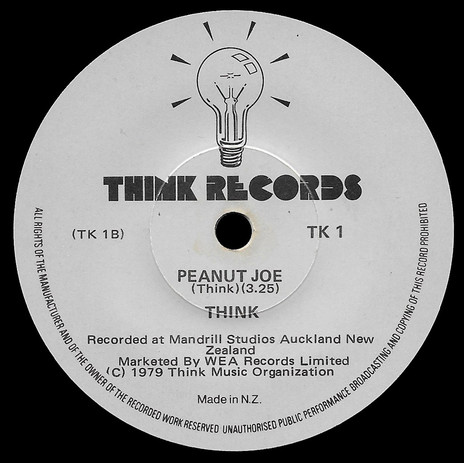

With touring funds, they recorded the deliberately commercial ‘Good Morning’ at Mandrill and released it on their own Think Records with an accompanying film clip. The B-side ‘Peanut Joe’, about the Dannevirke-born Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s draconian public assembly laws, was geared at their intended return to Australia. The single was distributed through WEA but, with no promotion, sunk without trace.

Its unique sound was due to Whitehead’s growing interest in guitar synthesisers. He had contacted the local Roland agency and worked a deal where he could hire the Roland GR-500 with expander unit. Think took full advantage of it with a guitar synth trumpet solo in ‘Good Morning’.

In Christchurch, Mark Nash called it quits and the band held auditions and brought in 16-year-old drummer Lyn “Vinnie” Buchanan, the son of jazz saxophonist Stu Buchanan, whom the Whitehead brothers knew from their days in the Christchurch Musicians Club in the 1960s.

But by then Think had become involved with a booking agent whose intentions were not entirely honourable. They were treading water and struggling to afford PA hire, and one night in early 1980, in a provincial North Island town, Whitehead – fuelled by too much bourbon – pretended to smash his guitar and basically surrendered. Allan Badger had no enthusiasm to protest and that was that.

In the end, Think were undone by a lack of good management when they moved to Australia. The tried-and-true formula of self-booking two months of work at a time in New Zealand was based on four or five years’ worth of contacts and experience in previous touring bands such as Beam, Judge Hoffman, The Movement and Graffiti.

Sydney and Melbourne were completely different beasts where agencies would use lesser-known bands such as Think in a new venue and once they had built up a good crowd they would be shoved out the door, replaced by Kevin Borich Express or the like.

Their sole LP We’ll Give You A Buzz is still a highly sought after chunk of vinyl all around the globe, although the master tapes were allegedly stolen from Stebbing Recording Centre in the 1980s. When a bootleg CD from an American web site was obtained years later, it was found to be direct from the missing master tapes. A pristine copy was returned to Warner Music New Zealand and finally made available digitally.