Marie, as she liked to be called, was in fact Mary Seddon, a Victoria University graduate who had recreated the type of café she had frequented in travels around Europe in the 1950s. The Monde Marie café attracted a university student crowd that reflected the beatnik-to-folk movement in the US.

Mary employed a combination of university students and folk singers to serve the Cona coffee and work in the kitchen. The waitresses followed Mary’s lead in brooking no nonsense from unruly patrons.

MacKinnon: “Although the Monde Marie was not licensed, Mary was working towards obtaining a liquor permit. I remember one night some American sailors arrived with bottles of alcohol. Mary whisked them straight back out. Later they returned, worse for wear, the ringleader being met with a spiked heel in the groin from Mary and a knockout punch from a waitress named Liz.”

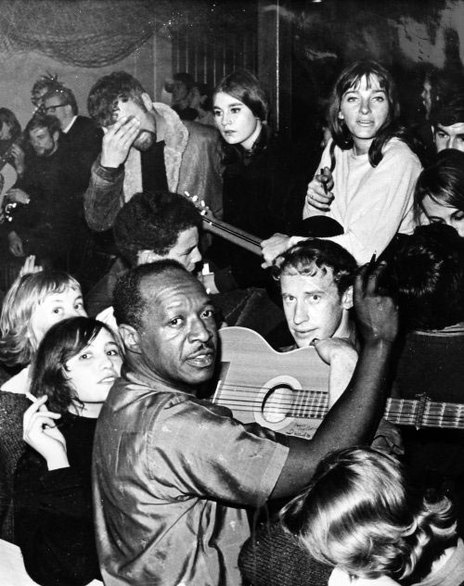

MacKinnon recalls mingling with artists such as Judy Collins, Josh White, Ravi Shankar and William Clauson.

International artists were frequent visitors to the Monde Marie after their Wellington shows. Ridiculously accessible by today’s standards, MacKinnon recalls mingling with artists such as Judy Collins, Josh White, Ravi Shankar and William Clauson. As often as not they’d strike up a tune or two, with the crowd joining in on choruses. MacKinnon bowled up to Josh White’s hotel room the following day “just for a chat about music”.

MacKinnon: “Following the Pan Pacific Folk Festival Lou Gottlieb of the Limeliters, and The Rooftop Singers paid a visit. Pete Yarrow from Peter Paul and Mary, and Theodore Bikel also called in following gigs. The international stars fitted right in with vibe of the café.”

The success of the Monde Marie encouraged the establishment of rival venues, including the Chez Paree and the Balladeer, in both of which Rod performed frequently. [Read about Wellington's folk coffee bars here]

MacKinnon: “But the Monde Marie was the original and the best. On a night when I might do as many as three sets in separate venues I’d maybe start at 8pm at the Balladeer but would inevitably end up at the Monde Marie at 1am.”

Growing up in the tiny West Coast settlement of Ngakawau, a service centre for the Stockton coal mine, MacKinnon’s life was changed at a variety show at the Marine Picture Theatre where, aged 13, he heard an acoustic guitar being played live for the first time. A job as a delivery boy financed the purchase of an unwanted guitar from a school friend for the princely sum of eight pounds.

Francine Turner, the guitar player from the Marine, gave him free lessons until he was ready to perform at the theatre himself. The applause as the curtains parted told MacKinnon that this was where he wanted to be. A stint fronting Muggs Mullins and the Tornados followed, playing the rock and roll hits of the day.

A move to Wellington to cement his future as a musician came in 1962, thus avoiding a career down the mine, the normal route for local lads. Calling in to the Monde Marie, Rod found an environment that immediately felt “right”. Val Murphy was playing as he walked in. After some determined pestering Rod persuaded Mary Seddon to let him audition. Impressed with his version of the Kingston Trio’s ‘Chilly Winds’, Mary invited him back for a set that very night.

From then on MacKinnon became a regular, often playing as many as five evenings a week. A typical night would see up to half a dozen artists performing in rotation, loosely scheduled by Mary and paid in coffee, sandwiches, a bowl of pasta and a pound or so in cash.

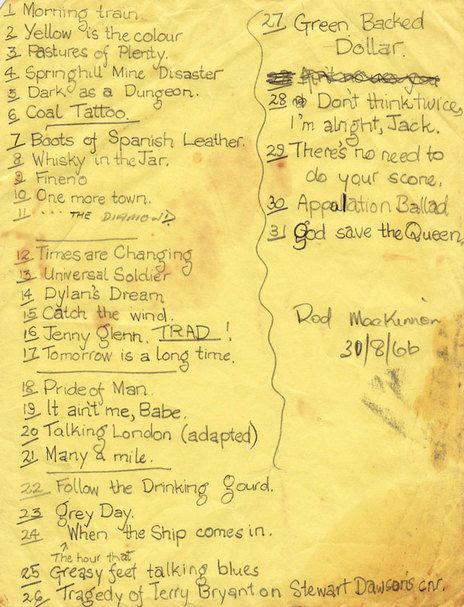

An evening’s set list would include around 30 songs, heavy on the Dylan covers. MacKinnon: “I was focused on establishing myself as a full-time professional musician so had literally hundreds of songs in my repertoire. This meant I could play for a whole evening if needed. The café owners such as Mary, and Frank Fyfe of The Balladeer, were very supportive of my ambitions and scheduled me to perform regularly. The pay wasn’t enough to survive on though so I had various jobs at wool stores and railway yards throughout the mid-sixties.”

Friendships developed and MacKinnon formed a trio in the Peter Paul and Mary mode, with guitarist Dave Hollis and vocalist Hillary Hind, which played together at the Monde Marie for a period of about six months.

MacKinnon: “Hollis was a wonderful guitar player, far superior to me. He arranged our songs and was a patient teacher as he shared guitar techniques with me.”

In search of talent, HMV A&R man/producer Nick Karavias was a regular visitor to the Monde Marie. Impressed with the trio, he invited them to HMV’s offices to discuss a potential recording contract. However taking him aside Karavias revealed he was really only interested in MacKinnon, causing an awkward situation with his bandmates, now also his flatmates. Rod moved briefly to Karavias’s house in Island Bay, then to the Lochiel flats in Karori.

MacKinnon recorded four singles for HMV but got off to a fraught start with the choice of first single.

MacKinnon: “I now had a recording contract but no manager, so relied on Nick as my mentor. He had a massive record collection that gave me exposure to a wide range of music.”

MacKinnon recorded four singles for HMV but got off to a fraught start with the choice of first single, a cover of Buffy Sainte-Marie’s caustic criticism of militarism, ‘Universal Soldier’. The ultra-cautious NZBC refused to play it on the grounds that, at the time, New Zealand had soldiers in Vietnam. ‘The Last Thing On My Mind’ was hastily recorded as a replacement track, re-using ‘Universal Soldier’s’ B-side ‘Walkin’ Down The Line’. Further track selections were made together with the HMV staff encouraging MacKinnon towards more commercially trusted songs – but MacKinnon recalls pushing back strongly at the suggestion he record ‘Pearly Shells’.

Recording was done at HMV’s Wakefield Street studios, with all vocals and instruments recorded simultaneously. Bruno Lawrence was on drums for the first two singles but by the time of the third had been banished from the studio, allegedly for smoking “jazz cigarettes”. Where tracks required extra musicians, instrument-playing staff from the nearby Begg’s music store were called in: a French horn player for ‘Genesis’, a clarinet player for ‘To Ramona’. For ‘To Ramona’ no mandolin player could be found so producer Patrick Flynn laid watch chains across the strings of a grand piano to imitate the sound.

MacKinnon: “Recording was done very quickly – one or two takes at most and that was it. The engineer Frank Douglas did a terrific job.”

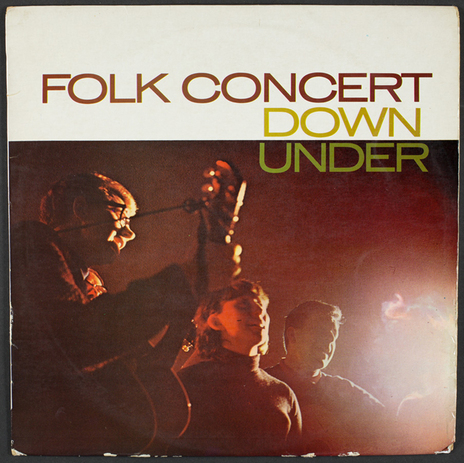

MacKinnon also contributed three tracks to the 1966 album Folk Concert Down Under which gathered together artists from the Monde Marie to perform live at the HMV studios when the café’s acoustics proved too difficult for recording.

Radio was generally very supportive of MacKinnon’s singles; two were released in 1965 and two in 1966. Relda Familton and Peter Sinclair both invited MacKinnon on to their radio shows. MacKinnon: “They were both knowledgeable and enthusiastic, and keen to see New Zealand artists do well, but had to tow the corporate line in not playing ‘Universal Soldier’.”

The rapidly burgeoning Wellington folk scene spawned not one but two TV shows. MacKinnon appeared on both There’s A Meeting Here Tonight and Just Folk. MacKinnon: “From memory Peter Cape was the producer of There’s A Meeting Here Tonight, if not the musical director. He paid a lot of attention to detail, and demanded perfection even if it took hours of takes. Bryan Easte had recreated a coffee bar set for Just Folk. Compared to the real thing it was a lot brighter, and smoke-free of course!”

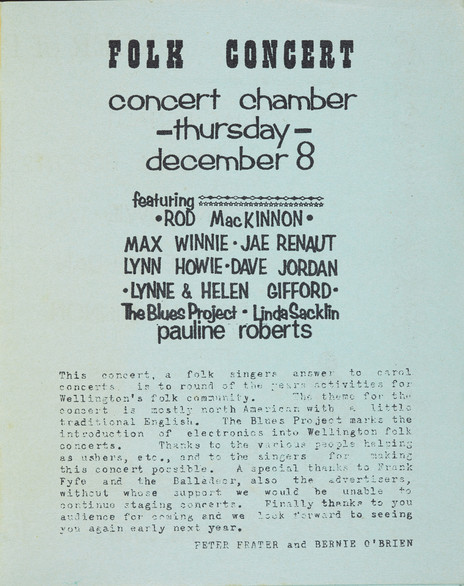

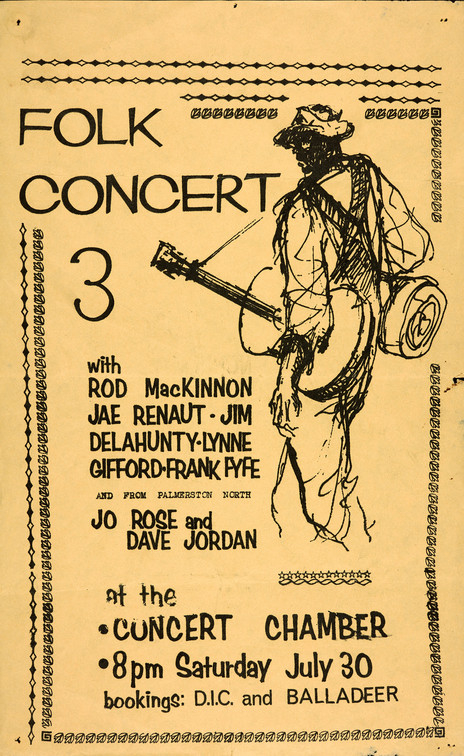

The arrival in Wellington of Australian Frank Fyfe saw the opportunities for live performances expand exponentially. MacKinnon: “Frank brought a drive and organisation to the scene. In addition to opening the Balladeer café, he organised regular Wellington Folk Festivals, first at the Concert Chamber of the Town Hall, then as demand for seats increased, at the Trades Hall in Vivian Street.”

MacKinnon appeared regularly at these festivals alongside numerous other folk singers of the day including Arthur Toms, Val Murphy, Jim Delahunty, Lynne Gifford, Jae Renaut, and Dave Jordan.

MacKinnon: “The folk scene was huge by this time, with magazines, a whole raft of venues, TV shows, the establishment of the Wellington Folk Club and a regular stream of visiting international artists. Posters in the streets advertising gigs featured sketches of local artists done by acclaimed photographer /artist David Eastman.

“The worst criticism I received was that I was trying to be ‘commercial’.”

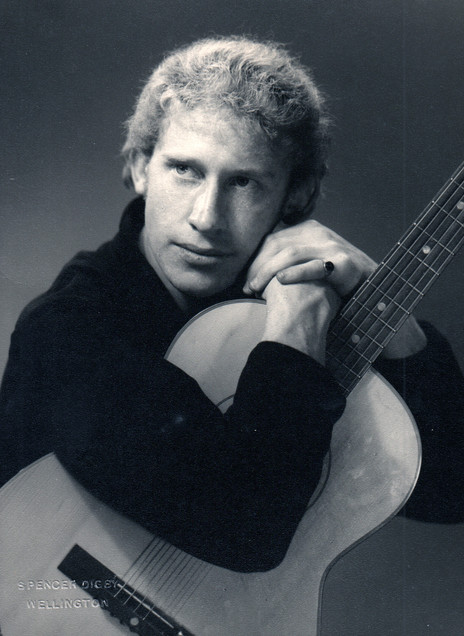

“There was something of a schism in the local folk artist community, very similar to that witnessed in the UK and US. There were the ‘purists’, who felt that real folk musicians played only traditional songs, and those keen on writing and performing newer songs. To me the newer songs had greater appeal, particularly those with a topical or political message. I pointed out to the traditionalists that all folk songs were new at some point. My clothes choice probably didn’t help – I had a sense of theatre from my days with Muggs Mullins; to contrast with my shock of blond hair, I dressed in black, eschewing the polo necked sweater, de rigueur for a traditionalist. It was all friendly enough though – I think the worst criticism I received was that I was trying to be ‘commercial’.”

Promoter Phil Warren invited MacKinnon on a 10-day nationwide tour with Normie Rowe and Mr. Lee Grant but out of the empathetic environment of the coffee lounges MacKinnon found the venues and audiences had little appeal. “I realised quickly that it was really the music and culture that I was attracted to – the commerce of the music business left me cold.”

Inevitably pressure came from the future mother-in-law to get “a real job” and MacKinnon stepped away from performing to become a full-time teacher by 1968. This coincided with folk being overtaken by pop and rock as the music of choice for teenagers, and the extension of liquor licenses from 6pm to 10pm saw a relatively swift decline in the café scene. “I parted ways amicably with HMV, and still have great memories of working with Nick.”

Since the heady days of the 60s MacKinnon has retained a keen interest in music. For many years MacKinnon ran a modest guitar school from his home in Greenlane Auckland with the by-line “No Sweat – the harder you try the harder it gets!” Occasional forays back to live gigs included a stint at the Gables in Herne Bay Auckland in the mid-90s, which brought MacKinnon and his wife Barbara into contact with jazz musicians. On realising that many of these had never been recorded MacKinnon started up Jazz Auckland radio from the Access Radio studios at Unitec, with support from Russell and Jan Hughes of the Alhambra. More recently MacKinnon has recorded some soon-to-be-released original songs at Kog Studios in Titirangi. He now lives on the Whangaparaoa Peninsula.

MacKinnon’s HMV recordings have been compiled and digitally re-issued under the title Hard Rain.