AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

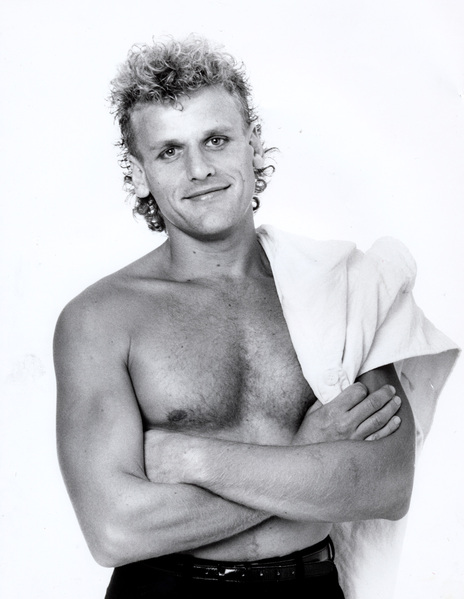

Peter Warren

aka Rooda

In band photos of the time, standing beside Dave Dobbyn with golden curly locks cascading about his head and wearing a signature uniform that included split colour Lycra pants, Rooda looked every bit the rock star. “That name was coined by a guy called The Future who was with me in a band called Lip Service. He called me Rooda because I was rude, as in not shy about saying whatever was on my mind. It was not a sexual reference as everyone thinks.”

A native of Auckland’s North Shore, Peter Warren burst into this world back in 1958 and from the start he was a restless and energetic soul. “Lord Bloody Go Fast”, as he was nicknamed by his paternal grandparents, responded to the challenge “I betcha can’t?” with a firm and definitive “I betcha I can.”

“I lived life at 1,000 miles per hour from the very start,” he says, “and could always go harder and faster than everyone else which meant when I got older, drinking more and being able to take more drugs than anyone else. Mum was hard on me, she always said she loved me the most, and worried that I might kill myself, she often locked me down.”

By Warren's own admission, it was pretty tough for his mum (Marie Josephine) struggling to keep four precocious boys in order through the long months when his father was away at sea.

Pete was a drummer from the start. “I was a tapper and tapped everything in within reach.”

Warren senior (John), a master mariner out of Middlesex in England, was like his son, something of a trickster who ran away to work the merchant navy aged 15. His first two positions ended up on the wrong end of U-Boat torpedoes, but a few days at sea in a lifeboat were nothing for this hardy kid who, despite the dangers, couldn’t wait to get back onto a working ship. When he eventually retired he tracked down the Captains of the U-Boats concerned and befriended them. Not one to hold a grudge, he was a mischievous, tough and hard working man, beloved by Pete, who considered him more like a brother than a father.

Pete was a drummer from the start. “I was a tapper and tapped everything in within reach.”

The endless tapping became something of a contest of wills between father and son. The father, tired of telling the son to desist at the dinner table, would wait patiently for the right moment then flick him hard across the right ear, an act carried out so frequently that Pete’s hearing in that ear remains somewhat lacking to this day. However, it was through all this ceaseless tapping that Pete taught himself the rudiments of drumming.

He was 10 years old when he finally obtained his first drum kit, a 1935 Olympic Vaudeville Kit, with pig skin vellums and Zildjian cymbals. He found it in the classifieds of the local paper and his mother agreed to pay half the $90 asking price. It was a big moment for the young Warren who had been working toward this for three years, delivering the NZ Herald in the morning and the Auckland Star at night. “It was a very rare model, similar to what Levon Helm played in The Band, and if I had kept it would be worth a fortune today. But hey, I was a kid and I had my sights set on eventually getting something new and sparkly, which I did when I was 13.”

The drum kit became Pete’s life. He set up in the washing room and started playing at 6:30am every morning. Then it was off to school, straight home after and back to the washing room. “The ceaseless noise and the endless complaints from neighbours drove Mum insane but she never let me know about any of it until many years later. She wanted me to get on and do my thing without having to worry. Plus having a drum kit downstairs kept me under control, which meant she had one less thing to worry about.

“Early influences were Led Zeppelin, The Beatles, Deep Purple, the Stones, Beach Boys, Hendrix, Chuck Berry and The Temptations. Other later influences were Miles Davis, Oscar Peterson Trio, Bill Cobham, Weather Report, Tower of Power, Emerson Lake & Palmer, Al Di Meola, Herbie Hancock, Buddy Rich Big Band, Ellington, Zappa, George Duke, and Dr Tree. A wonderful lady named Dianne Hargreaves, who lived at the bottom of my street, introduced me to this music at age 12.

“My mate lived next door to her and when hanging out at his place, I would hear this mad piano-playing coming from her place. I remember going up to her door (which was always open) and peering inside. Her whole house was filled with records, posters and memorabilia and at centre stage was an upright piano. From that moment on I was a fixture in her living room. Dianne forgot I was there and played her records and the piano, always chain-smoking. Except for the smoking, Dianne was a massive influence on me because she took off my blinkers and opened my mind to the possibilities of music.”

At around the same time Pete met Frank Gibson Sr, a man he came to call his “second father”. “When I turned 12, Mum decided that I was old enough to bus into town (central Auckland) on my own and I would head off in search of music. I was in Lewis Eady’s music store one day when I heard this drumming coming from the stairwell. I went up to have a look and discovered Frank Gibson Sr’s Drum Shop on the top floor.

“After that I spent so much time there that I started to refer to Frank as my second dad. He was a mentor, a friend and the first person to really believe in me as a musician. One year Frank gave me his own personal be-bop jazz kit as a birthday gift, a possession I treasure to this day. I was touring Europe with Disciplin A Kitschme when I got a letter from my brother telling me that he had died. Now, I am a bit of a hard man, but Frank’s death really caught me off guard and I wept openly for days.”

Mary Warren had all secured special permits that allowed Peter to play on licensed premises (back then the legal drinking age was 20) at Bob Sell's Troika Dine & Dance in Auckland's Fort Street.

For Pete it was a passport to the world and allowed him to say yes to every gig he was offered.

By the time Pete was 14 the family had added a rumpus room to the house. It turned out to be the perfect rehearsal space for his first band. Ethos was a psychedelic rock band of sorts that featured fellow Westlake Boys High student Don McGlashan (later of Blam Blam Blam and The Mutton Birds). Of course the addition of electric guitars and a bass to the drum noise gave the neighbours even more grief, a burden Pete’s parents continued to carry in stoic silence.

“Ethos was Don McGlashan (lead vocal, keyboards), Scott Colhoun (vocals, bass), Brian O’Donnell (vocals, guitar) and me on lead vocal and drums. At about the age of 14 we were playing three nights a week at Bob Sell’s Knightclub (the first real nightclub on the Shore, located on the roof of Shore City). The set was stuff like Hendrix, Deep Purple, Yes, Steely Dan, Stones, Steppenwolf, 10cc, Rory Gallagher, Queen, Cream, Blind Faith, Elton John, Grand Funk Railroad, Chicago Transit Authority, Van Morrison, Mamas & Papas, Beatles and CSNY. We were also writing our own stuff as well.”

His next gigs which included a six-month stint with Prince Tui Teka when he was 16.

“The Prince heard I was a handy drummer and wanted to interview me over dinner which turned out to be fish and chips on the bonnet of his Ford Falcon. We played Glenfield’s Thunderbird Valley Inn for six weeks then The Flying Jug in Panmure before heading down country to play The Trees in Tokoroa. After that I did a season with Tom Sharplin at the Mandalay in Newmarket. I played for anyone who needed a drummer. I wasn’t fussy and I didn’t care about the money, I just wanted to play.”

Lip Service 1977-1980

Pete was 18 when he formed Lip Service with Dave Marshall (formerly of Waves) and an old guitarist mate from Westlake Boys, Rob Guy, (AKA Revox). “We were basically a bunch of long haired hippies who arrived on the scene just as punk was exploding and while we were influenced by punk, we weren’t considered punk because we played too well. The punks despised us despite the fact we could play harder and faster than them, and feeling at bit out of place the only thing we could to do to bring us up to date was to cut off our hair.”

The band, with a rock sound that could be described as new wave, immediately hit the road. “We would arrive at a venue, set up our stage, (a complex affair of white polythene and air conditioning vents that required nearly three hours to assemble), sleep for an hour and then play for three to four hours, sometimes to just one person. Often all we could afford to eat after the show were chips and a burger, then we would party, sleep and in the morning we would be up again at 8am and packing down before hitting the road again.”

Through constant gigging the band built up a big enough following for the guys to make a living but it was via manager Charlie Gray and the summer touring circuit that the band found its biggest paydays. The summer tours were very lucrative and basically paid for us to be a touring band for the rest of the year.”

Manager Charlie Gray also handled Th’ Dudes, and Lip Service often found themselves on the same bill in the support slot. “This is how I got to know Dave [Dobbyn, Th’ Dudes’ songwriter/guitarist]. We shared a similar sense of humour and got on really well.” But before the famous relationship blossomed, Lip Service had one more mission to complete.

They came to the attention of John McCready at CBS, who signed them up to a four album deal.

They came to the attention of John McCready at CBS, who signed them up to a four album deal. “We only ever actually made one album, the self titled Lip Service record. We recorded it at Glyn Tucker Jnr’s Mandrill Studios with producer Graeme Myhre. It was released in 1980 and went straight to the bargain bins.”

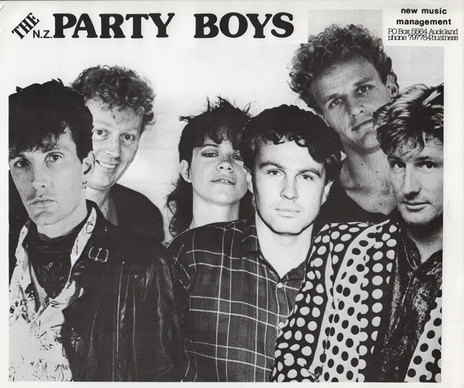

DD Smash

In 1981 Dave Dobbyn approached Pete and Rob (Revox) about starting a new band. "We joined Dave and Lisle Kinney (Hello Sailor) and did six weeks of secret rehearsals at the Rumba Bar in central Auckland before heading off to Hamilton and our first “test gig” at the Hillcrest Tavern. The place was packed; people were hanging from the rafters and going crazy and we realised that we were onto something pretty special.”

Pete was a famously loud drummer whom Dave had previously nicknamed “Smash”. “It was the usual struggle bands have with names. We tried all kinds of things then Dave’s manager suggested Dave Dobbyn’s Divers. We were running out of time with our first gig coming up fast but there was no way I was going to be one of Dave’s divers so I suggested DD (Dave Dobbyn) Smash.”

Pete and Dave were together for eight years, a near decade that included three huge selling DD Smash albums, Cool Bananas (1982), Live: Deep In The Heart Of Taxes (1983) and The Optimist (1984), a sojourn that included Dave’s big solo breakthrough with his work on the Footrot Flats soundtrack (1986).

DD Smash had been in Australia for several years prior to the career defining success of Footrot Flats, a time Pete describes as a "hard slog". Signed to Mushroom Australia, they were gigging hard trying to build an audience. Aside from their own gigs, they scored prominent support slots on tours with some of the biggest names on the Australian tour circuit, including Midnight Oil, Mi-Sex and Dragon.

“We were playing as many as nine shows a week and mostly losing money. To compete properly on the scene, we needed trucks with sound and lighting gear and a two to three man road crew, and it all costs. Basically, the support slots on the big tours subsidised our solo shows.” Despite all of this, the band’s records failed to sell.

Dave Dobbyn’s 1986 breakthrough solo hit from the Footrot Flats movie soundtrack ‘Slice of Heaven’ (No.1 on the Australian charts for four weeks) changed it all. Crowds improved, as did the band’s quality of life. But as Pete explains, “The writing was on the wall for me and I failed to see it.”

It was clear by now that Dave’s future was as a solo artist and it was during the first sessions for the Loyal album (1988) that Pete was taken aside by Dave’s manager and given his marching orders.

Pete had been a heavy opiate user for many years and concedes that the drug was getting in the way of the relationship. “Dave hated confrontation and it had become my job to organise the band and make sure they knew and understood the song arrangements, on top of this I took care of all the hard personal stuff that goes on between band members and looked after Dave who suffered terrible stage fright. It was my job to care for him and coax him out onto the stage. This was the tough part of band life and I soaked it all up.”

The abrupt end came as something shock to Warren, who had stayed true to Dobbyn throughout difficult times, line-up changes and the excesses of the rock and roll scene. It caused him some degree of grief but he concedes that the breakup was mostly his own fault. The famous relationship had come to an end and it was time to move on.

Between Dobbyn gigs, Pete spent the 1980s as a drummer for hire and did a stint on the Australian cabaret circuit with Marcia Hines. “It was all very glamorous and a step up from the grimy rock scene but it wasn’t for me.” He also did some work for The Divinyls, before they hit the big time with ‘I Touch Myself’. Back in NZ he played sessions for advertising jingle king Murray Grindlay, Netherworld Dancing Toys, Shona Laing, and filled the drum stool for Satellite Spies in 1986 when they supported Dire Straits on the New Zealand leg of their massive Brothers In Arms Tour, all the while leading his own band, Rooda. In 1987 Peter Warren joined a re-formed line-up of Pop Mechanix, which also featured guitarist Mark Bell (Blam Blam Blam, Coconut Rough). Leading up to this the band called themselves the Big Rehearsal.

In between all this he got to share a joint with Bob Marley and play football with Rod Stewart, both of whom he met while working as road crew. Later he joined Midge Marsden on his 1991 tour of Australia, the UK and America.

“I had a reputation as a ‘trouble shooter’ drummer because I could play reliably to a click track in the studio and deliver a decent beat, often in one take. And if for some reason a drummer couldn’t make a gig, I would get the call and sit in and pick it up as went along. I didn’t need to know the songs.”

The UK and beyond

In 1993 came the sort of opportunity that every drummer for hire dreams of, an invitation to audition for Led Zeppelin. The band was preparing for their 25th anniversary and a big tour was on the cards. Unbeknownst to Pete his name had been put forward by a friend, Auckland based British musician Malcolm Foster (The Pretenders, Simple Minds), and after a 4am phone call from Zeppelin’s management enquiring about his availability, he flew to the UK to play an audition that never happened.

He turned up to the rehearsal studio at the appointed time but Led Zeppelin never showed.

He turned up to the rehearsal studio at the appointed time but Led Zeppelin never showed. The 25th anniversary celebration of one of the world’s biggest ever bands failed to eventuate but the excursion turned out to be a positive thing for Pete. Away from the New Zealand drug scene, he decided to clean up. He went cold turkey, approaching the three weeks of sweat, pain and sleeplessness with his usual stoicism. “I did this to myself and had to take care of it myself.” This was the end of Pete’s long relationship with the needle.

Clean, he teamed up with Malcolm Foster, who was on a break from Simple Minds, and formed a Led Zeppelin tribute band. “We were building a big reputation and word got out to Robert Plant who came along to see us. He was so impressed that he gave us his endorsement and that opened doors for us right across Europe. We got to play all the big cities but the singer, who could do Robert Plant so convincingly that people actually thought he was Robert Plant, struggled with stage nerves and eventually packed it in and that was the end of that.”

Next up was 2Karsex. “I answered an advert in the New Musical Express for a rock band seeking a vocalist and got the job.” Pete had long provided backing vocals as part of his drummer for hire package and can sing up a storm. Managed initially by New Zealander Chris Malloy and then by Rod Smallwood (Iron Maiden), the band built up a solid reputation on the London pub circuit and just as things were starting to look like they might be headed for the bigger time, Smallwood decided to divest himself on much of his management portfolio and concentrate on Iron Maiden. The momentum was lost. Regardless, the biggest success of Pete’s career was just around the corner.

Disciplin A Kitschme 1995-98

Disciplin A Kitschme is a Serbian band, a spinoff from the seminal Yugoslav new wave bands Šarlo Akrobata and Ekatarina Velika. Formed in 1982, Disciplin is centred on the talents of Dušan Kojić "Koja (Black Tooth) and has had several incarnations in style ranging from punk to funk, jazz-fusion, Motown and jungle, all with a good dose of Jimi Hendrix inspired rock thrown in for good measure. The band has taken on a blues inspired sound in its current manifestation.

The Pete Warren era Disciplin A Kitschme recorded two albums. I Think I See Myself on CCTV (1996) was recorded at Iron Maiden’s Fortress and Heavy Bass Blues (1998) was recorded at Adrian Sherwood’s ON-U-Studios.

“We were the first true drum and bass band in London and were championed by the likes of John Peel, Fatboy Slim, and Adrian Sherwood. The real deep clubbers loved us but our records never sold well in Britain. In Eastern Europe it was a different story. We had three No.1 singles across Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria and Romania and our albums sold around 150,000 units apiece but there was no royalty gathering system in these territories back then and the only money we made was from gigs. We were playing sold out arenas and if we had based ourselves in Serbia we could have lived like kings. But our base was London and once we changed the currency into sterling it was worth bugger all.”

It was Pete’s relationship with Rosie, the mother of his two British children, Genie Josephine and Cayo Tobias that caused Pete to leave the band. “I was away touring a lot and it was putting a big strain on my relationship with Rosie and I thought if I left the band and became more available it would help. In the end my drugs, partying and general bad behaviour were more than she could cope with.”

Surrey, Shark Attack and heading home

His relationship in tatters, emotionally spent and on the “bones of his arse”, Pete left London and found a home at Pound Farm in the rural heart of Surrey, first in a horse van and then in a broken down VW Kombi. It was at the local pub, The Black Swan, that Pete met the players that were to become Shark Attack. Again taking on lead vocal duties, Pete, tanked up on tequila (“I was not a natural frontman and needed a few drinks to loosen up”) led the band through their regular Sunday night slots. They became a favourite of the local chapter of the Hell’s Angels who got them a slot on the Bulldog Bash, the gang’s annual national gathering. It was a lucrative gig and caught up with the Angels as they were, the drugs were cheap and on tap and Pete found himself spiralling once again into the world of partying and drugs, this time cocaine.

It was during this time that Pete met Pavla, a young Czech woman who was over in the UK improving her English. “She was half my age and I just thought she was just a beautiful young woman playing with an older man for a bit, but she stuck around. I had ruined every relationship I had ever been in through my partying ways and I thought if we are going to do this, it was time for me to ‘man up’ and face my demons.”

With Pavla’s encouragement, Pete sorted himself out and with the relationship blossoming, the couple set off for the Czech Republic to meet her parents. “I was about the same age as them and a bit rough and ready and they were not pleased at all and after a couple of weeks insisted I go. I headed back to NZ, got a job, set up a home and a few months later Pavla arrived and we have been together now for 15 beautiful years. Basically she saved me and helped me to become a better man.”

In New Zealand, Pete began a labouring job with a construction company that specialised in big projects like shopping centres and road construction. “I surprised myself because I really loved the work,” and his enthusiasm and reliability saw him being offered ever more responsibility. He found his second calling in Environmental Management, specialising in Silt and Erosion Control.

His job was to make sure that silt and soil did not escape construction zones and pollute natural waterways and his ideas and innovations saw him becoming an increasingly in-demand speaker at conferences and exhibitions. “I didn’t wear a suit, just my muddy work clothes and spoke passionately from my heart about doing the right thing for the environment and it was, I think, for these reasons that the people I was speaking to related to what I was saying.”

Then bad luck struck. “I got trapped beneath a 220kg roll of anti-erosion fibre the crew and I were carrying up a bank. The pain was excruciating but I got up on with the job. As the days passed the pain became unbearable. I was taken to hospital and scans revealed major back damage.”

With the healing underway Pete found himself making music again.

After four years on the construction site, it was over and the next three years were spent recuperating. With the healing underway Pete found himself making music again and with the encouragement of one of his brothers, he decided to go teaching and pass on his knowledge.

He placed an advert in the local paper, the Rodney Times, and got a response straight away. “It was a light bulb moment for me because I realised that I absolutely loved teaching. Most drum teachers say you can’t teach the art until kids are 8 but I teach from 5 years on. It’s a great age to start drumming and the kids are like sponges, they just soak it all up.”

Rather than teaching a prescribed formula, Pete’s methods are intuitive and he approaches each pupil in a unique way, a method that keeps his services in demand at schools and homes across the North Shore. “I’ll teach anyone who wants to learn, I just love it.”

“I am not only grateful to be alive,” he says, “but grateful that I met a woman, Pavla, who made me feel grateful to be alive and I am grateful that she puts up with me because at heart, I am still just a lad. I am also grateful for my children, Layla Anne and Sebastian Charles. I can only hope that the example of my life lessons will help make their journey through life a little easier.”

After Disciplin's first appearance on John Peel’s iconic BBC radio show, Peel was amazed at the intensity of Pete’s drumming and thereafter referred to him as "the Human Beat Machine".

Mushroom Records

CBS

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air