Harwood grew up in Hawke’s Bay. Her father played upright bass and was the music lover in her family. When he brought home the “entire contents” of a jukebox in 1964, the sounds of the Beatles, Dusty Springfield, The Hollies, and Manfred Mann left Harwood “stunned”. She was four years old and hooked; she pored over the discs, enjoying the hits but relishing the greater freedom the B-sides offered. This was often “where musicians hid their truth: on the underbelly of the radio-friendly hit”. Dusty Springfield was a favourite. “She never over-sang – no vocal acrobatics in sight”.

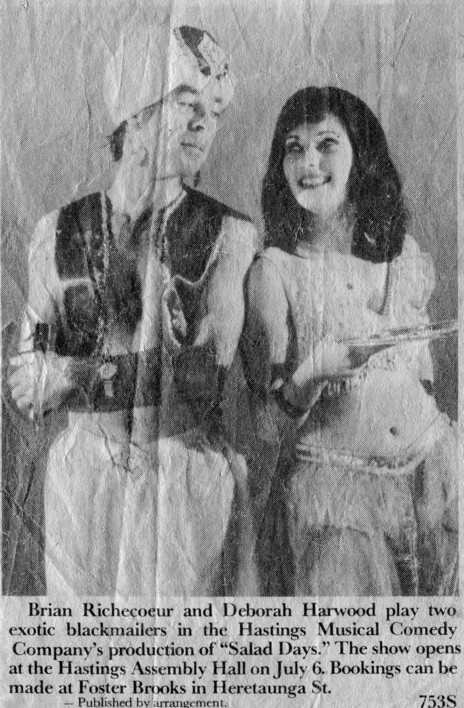

In 1978 Harwood got her first job at a Napier radio station; work at an advertising agency followed. A couple of musicians invited Harwood to sing in their band, Raven, but she brushed them off. They persevered and – despite her aversion to singing in public – she took the plunge. Raven played a couple of nights a week in pubs, covering hits of the day plus a smattering of punk. Harwood’s two years with Raven were a baptism by fire; she remembers belting out songs without any foldback, which caused the beginnings of throat nodules.

Around this time she started writing her own songs, an innately emotional process. “They seep out of your core. You are them”. She would write at pace late at night, and find a pad full of lyrics by her bed in the morning.

AS THE RECEPTIONIST AT HARLEQUIN STUDIOS, HARWOOD “WAS IN HEAVEN.”

Soon, Harwood was feeling the pull to Auckland. In Hawke’s Bay, Raven supported many of the touring bands, including The Pink Flamingos, The Crocodiles, and Lip Service. It was Peter Warren – aka Rooda, the drummer in Lip Service – who said, “get your arse to Auckland”. In 1981 she left the Bay and her job, filled her VW with her things and drove north, with no definite plan in mind but that overwhelming love of music driving her on. “When I went to Auckland I was finding my way,” she says. “I thought I’d learn a bit about how it worked up there before I sang.”

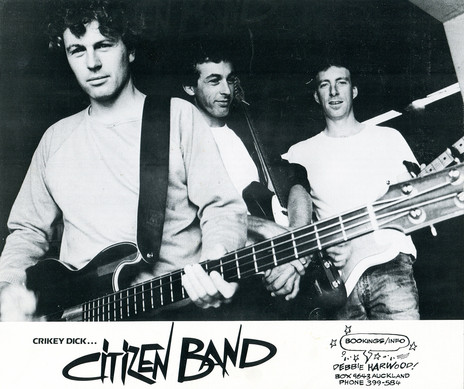

One New Zealand band held a special place in her heart. When she recognised a familiar drum pattern coming out of the studio, she put her head around the door. It was Mike Chunn, formerly bassist with Split Enz and Citizen Band, tapping out the drum intro to ‘Crosswords’ from the Enz’s Dizrythmia album. Chunn was then studio head at Harlequin and their friendship was “immediate”, forged by a shared love of New Zealand music. She did the rounds of recording studios and got a job painting the walls at Harlequin in exchange for some studio time. Soon she was the receptionist, with musicians such as Graham Brazier, DD Smash and Blam Blam Blam trudging past her desk. “I was in heaven,” she says, “listening to the incredible sounds emerging from the studio. I knew this was home for me.”

Harwood joined Chunn in a new professional venture, launching the New Zealand arm of Mushroom Records. Again, Harwood’s passion for music steered her decision-making: “There was no money. I worked for a pie a day and a pint on Fridays, but there was nowhere I would have rather been.”

Mushroom NZ signed The Dance Exponents and DD Smash and soon Harwood found herself heavily involved in music promotion and tour management. Her first assignment was road-managing Blam Blam Blam’s 1982 national tour, then tours by Dance Exponents and The Screaming Meemees.

This wasn’t a desk and telephone job, Harwood drove the car hauling the lights, lugged the gear, set up and ran the door. At this point in her life Harwood was ticking off nearly every job in the music industry, fuelled mainly by a love of the craft and camaraderie. Everyone mucked in on the tours at that time, with the creativity of the band members expressed in screen-printed posters and hand-made sets – everything on a shoestring.

In the early 80s music scene, sexism was rife.

In the book Kiwi Rock Chicks, Pop Stars & Trailblazers (by Ian Chapman, HarperCollins, 2010) Harwood reflects on being a woman in a management role in the early 1980s music scene. At the time she didn’t dwell on what she faced, but every day sexism was rife. “It was always assumed I was ‘managing’ the band because I was sleeping with one of the boys.”

Harwood excelled as a tour manager, bringing bands in on budget and avoiding the financial meltdowns all too common in the industry. She had proved herself in a tough environment and now, with the distance of years, recognises the inequalities at play.

“My natural progression should have been that I ended up running a record company or similar. Through that time women were always assistants, never the heads of record companies.”

She was still living gig to gig, earning little or no money and sleeping on friends’ sofas. In 1983 Auckland band Big Sideways approached Harwood for help. Big Sideways were not a run-of-the-mill rock outfit, they reflected a Pacific Auckland vibe with funk and reggae influences. On their 12" EP Harwood sang BVs, along with Josie Rika, and then she began singing with the band. Big Sideways reached its peak supporting Split Enz on a national tour; after a line-up change Harwood became lead vocalist and her brother Justin joined them on bass (he would later be a member of The Chills and Luna).

After the Enz played a show in Tauranga, Tim Finn and Eddie Rayner approached and asked her if she would be interested in running a small label with a view to signing up local acts. She agreed and Enz Records was born. It was a pie and pint time again, but this time there were maybe “two pies a week”.

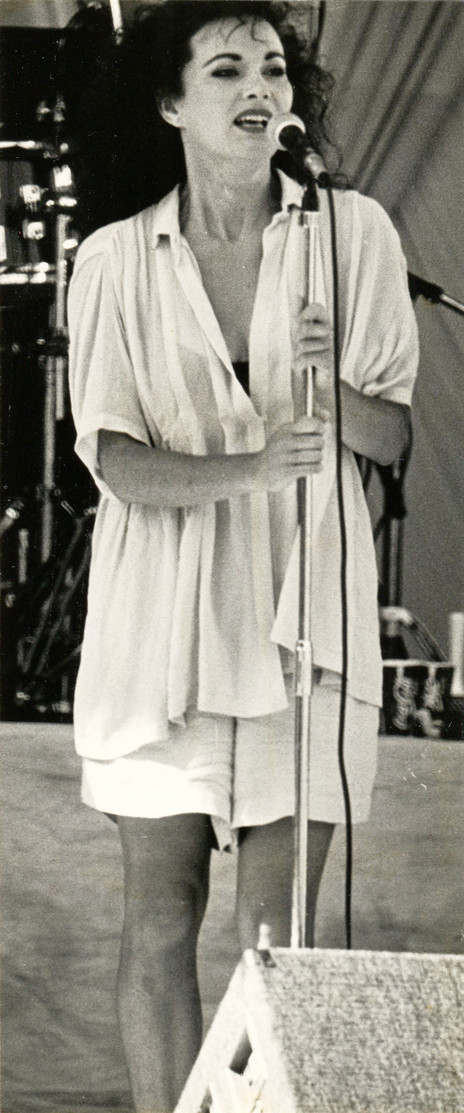

Big Sideways broke up on the day they were offered a publishing deal from Mushroom Records, but this opened the door for Harwood in more ways than one. Mike Chunn asked her to record her first solo single. In 1984 ‘If That’ll Make You Happy’ was released through CBS. Harwood fronts a full studio band and delivers a smooth-as-silk cover of a song by Gladys Knight and the Pips. The single won her Most Promising Female Vocalist at the 1985 New Zealand Music Awards.

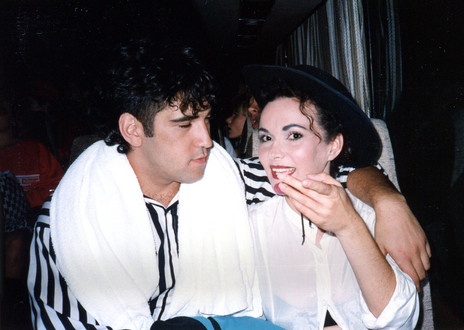

Harwood had arrived as a solo act, but the awards ceremony itself proved pivotal in her life. That year Peking Man vocalist Margaret Urlich won Best Female Vocalist and Dianne Swann was a nominee in Harwood’s category. Annie Crummer was also present to perform a song, and the four women had a great time getting to know each other. “Annie and I were already firm friends and singing backing vocals together on numerous recordings,” says Harwood, “but this event definitely sowed the seed.”

When the women who became the Cats met, “The sparks flew – it was chaos, but in a really good way.”

The Listener magazine requested an interview and photo sessions with all four vocalists for a story about emerging female musical talent. “The energy in that room was out of control,” remembers Harwood. “The sparks flew – it was chaos, but in a really good way – I felt really sorry for the poor journalist and photographer [Douglas Jenkin and John Reynolds].”

Harwood recorded a second single ‘Just To Be With You’ (released on Reaction in 1985) and, in 1987, ‘Blue Water’ with Johnny Bongo. ‘Blue Water’ won the ‘Most Promising Group/Duo’ at the 1988 music awards, and Harwood was offered two record deals: “both of which fell through at the eleventh hour.”

When The Cat’s Away found that the New Zealand music industry was still very much a boys’ club. “We all felt like part of the gang with fellow musicians – within our bands definitely, we had enormous respect from the other players – but the industry was male heavy in a different way. I always felt we were in this together fighting the cause, which was New Zealand music. It was almost impossible to get airplay then, so it felt like we were taking part in a movement against old thinking. Not the male/female thing but the New Zealand music thing. I experienced a lot more harrassment about being a musician than a woman.”

“It was extremely uncool to be a New Zealand musician in those days. Extremely. If you look up Th’ Dudes’ chart placements you’ll get an idea. All of those ‘classic’ Kiwi songs that we consider iconic now didn’t see the light of day at the time, and most of those bands broke up exhausted and broke. It is only now with a change in attitude about New Zealand music that everyone looks back and lauds those musicians and songs. At the time they were treated like scum.”

For the women, the decision to join forces seemed a natural progression from the joy of being together and feeling an “almost uncontainable rush of adrenaline and excitement”. Harwood remembers suggesting they all take time off from their respective bands and the grind of trying to carve out solo careers to do some gigs together. She already knew vocalist and actress Kim Willoughby from working with her post-punk band The Gurlz, and when she jumped on board the Cat’s line-up was complete.

They assembled a set list of favourite songs and debuted at Wildlife nightclub in Auckland to a packed crowd. Five shows later they walked away with 500 bucks each. Harwood was on a high. “I bought a $500 pair of shoes that looked like dalmations – insane. Money was never the motivation and it was a real shock to finally be paid for my efforts.”

Harwood and the Cats knew they had something organic and special. While it didn’t stop Harwood from forming a new group called The World with brother Justin and Andrew Todd, the “colossus” that was When The Cat’s Away was only beginning to rev up. In the summer of 1986-87 they went on the first of seven national tours. A Cat’s Away show would comprise of an eclectic set list of loved songs of all genres, with each performer taking their time to lead and shine with four-star back-up.

Harwood, Crummer, Urlich, Swann and Willoughby were at the peak of their energies.

When The Cat’s Away was a collective effort, a live show that fed off the natural love the performers had for each other and for the material. Harwood, Crummer, Urlich, Swann and Willoughby were at the peak of their energies and harnessed a feel-good inclusivity that translated into packed audiences.

In 1987 a TVNZ documentary crew followed the group on a series of gigs throughout New Zealand and the concert film won Best Documentary at the 1988 Listener Film and Television Awards, an interesting development considering the letter Harwood received from TVNZ before the film aired, downplaying expectations. She remembers it saying “how disappointed they were with it, that they were moving it from its prime spot on a Sunday night to late on a Tuesday because it had no merit. They weren’t going to promo it at all. Well, it aired, rated through the roof and won doco of the year.”

The documentary captures everything that made When The Cat’s Away an enduring cultural memory for a generation of Kiwis. They deliver international pop hits (‘Boogie Nights’, ‘Lady Marmalade’) and classic Kiwi tracks (‘Be Mine Tonite’, Dave Dobbyn’s ‘Guilty’) side by side. The criteria was “if it’s good and we like it, it’s in”. As soon as the five singers tumble onstage they are ready to have as good a time as the crowd.

In June 1987 a live album was released, reaching No.39 in the charts and achieving gold status. In November 1988 ‘Melting Pot’, the Cats’ third single – a cover of British band Blue Mink’s ode to multi-racial utopia – entered the NZ Singles Chart against a field of international artists such as U2 and Guns N’ Roses. It reached No.1 in December.

Again this achievement was all down to the women themselves, with the industry playing catch-up. As Murray Cammick says in his AudioCulture profile of When the Cat’s Away, the group’s story “is far more do-it-yourself than observers might imagine.”

The group paid for the recording of ‘Melting Pot’ and presented it to the head of CBS. The video was also a do-it-yourself effort and, along with the TVNZ documentary, sums up their appeal. It is loose and engaging, showing five spunky but relateable women front and centre doing what the hell they wanted.

CBS might have been surprised at the success of ‘Melting Pot’, but Harwood wasn’t. In Kiwi Chicks, Harwood expresses annoyance that the group itself was never signed to a label, although several of the members were as solo artists. “I always believed our greatest asset and power was the collective magic. It was a new concept at the time … I felt we could have run the solo careers alongside When the Cat’s Away, and it could have boosted the solo careers. But the record companies saw us as competition to the individuals.”

Ten years later a hand-picked group of young Brits would be hot-housed, packaged up with different personalities and presented to the world as exponents of “Girl Power” – it must have been galling.

“I always thought of us as having no co-relation at all to the Spice Girls except for the fact we were women across the front of a stage,” says Harwood. “People don’t think the Beatles and the Hollies are the same because they are boys playing instruments in a band. Yeah, I still think of us as musicians first … not women musicians. People will often say ‘When the Cat’s Away, the most successful female band in New Zealand.’ And I’m, ‘No, the most successful band in New Zealand’. We’re not in a ‘girl’ category. We broke all live attendance records of any band in New Zealand. Those things really do rile me.”

On the 1988-89 tour, the Cats played to over 100,000 people – but Harwood was suffering.

Hot on the heels of ‘Melting Pot’, the national tour of 1988-1989 “grew into a monster”. The Cats played to over 100,000 people and while it pulled the money in, Harwood was suffering. Years of touring and singing in smoky pubs meant she was living with “golfball-sized nodules” on her throat. She could barely sleep or breathe. She had an operation at the beginning of the tour and struggled to perform.

Meanwhile, the Cats were reaping awards, including Entertainers of the Year and the coveted Group of the Year award at the New Zealand Music Awards. For the first time the Cats juggernaut started to cause problems, Harwood was physically exhausted and while the singers loved their time onstage, backroom dramas were a drag. Music execs were looking at the Cats’ menu, planning moves. “It started to feel as if everyone wanted a piece of us and we couldn’t be bothered with that. The pressure took away that pure joy we had experienced early on, rehearsing in the Domain together, eating sultana pasties. Once that went, it became a chore.” The group decided to disband.

Harwood put her own career aside and, with her then-husband, singer Rikki Morris, moved to Melbourne where Morris had signed to Mushroom as a songwriter. She had recently become a mother to Marlon, the first of their two children. But within months of arriving Harwood was invited to join Jimmy Barnes’s band as a backing vocalist.

For nearly two years, Harwood toured with Barnes; the experience gave her some of the most satisfying moments in her career. They travelled all over Australia, performing shows in massive venues such as the Sydney Entertainment Centre and the MCG. “It was my life,” Harwood recalls. “We flew in small planes around the coasts of Australia to play shows in dust bowls where the people had walked for days to come and see their hero play. It was ‘real’ rock ’n’ roll. Jimmy Barnes is a beautiful man and a force, unlike anyone else I’ve ever met.

“My memories of that time are epic. I did the Two Fires tour, then a few others with Diesel as well. Kevin Borich was in the band for Two Fires too. Then [Barnes’s hit album] Soul Deep happened and I annoyed the bejesus out of Jim by banging on about this amazing singer in New Zealand, Annie Crummer, so she popped across for the Soul Deep shows and live DVD.”

During this time, says Harwood, she found her voice. “The nodules had healed, it was the best time vocally for me. I met my match with Jim: my voice is huge like his so I loved doing the duets with him, on ‘Die To Be With You Tonight’, ‘Good Times’ and so on.”

There was a downside, however. All this touring damaged Harwood’s hearing, and she developed “horrific” tinnitus. The couple decided to come back to New Zealand in 1992, and two years later their daughter Gala was born.

In the mid-1990s Harwood produced an album of her favourite love songs.

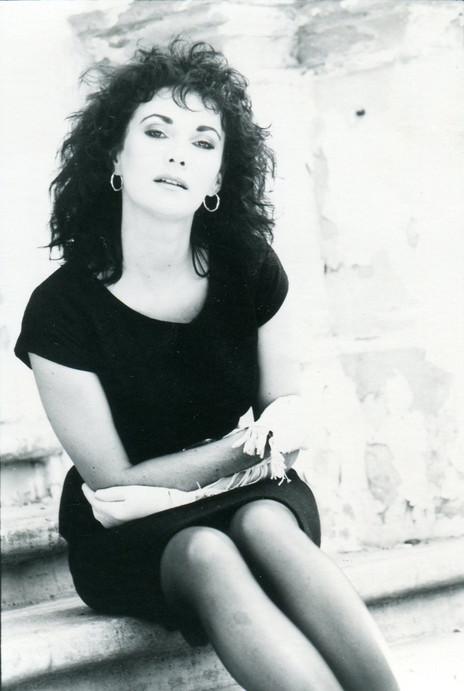

In the mid-1990s Harwood decided to fill a gap she saw in the music market, producing an album “for tired mothers”. She sold the family home and produced Peaches – So This is Love, an album of her favourite love songs on which she was joined by some of her favourite singers (among them, Cats alumnae Margaret Urlich and Kim Willoughby, plus Moana Maniapoto, Leza Corban, Betty-Anne Monga, and Vicki King). Harwood also produced the album, and was a finalist for producer of the year at the 1996 New Zealand Music awards, up against heavyweights The Feelers and Bic Runga. Harwood considers being a finalist for her self-funded, self-produced record as one of her proudest achievements.

In 1997 Harwood and Morris set up The Bus, a recording studio in Devonport, and over the next five years produced albums, singles and jingles. “I was back in my happiest place – the recording studio – it was more than a dream for me and I sat in the producer’s seat there for some of the happiest days of my life.” Harwood continued to work in front and behind the microphone, hosting nationally syndicated radio shows focusing on New Zealand music, appearing on Max TV and performing with The Wide Lapels and her own band.

When The Cat’s Away reunited in 2001, minus Dianne Swann, who had relocated to the UK. They chose to cover fellow Kiwi pop star Sharon O’Neill’s 1980 single ‘Asian Paradise’, produced by Ian Morris, and invited O’Neill to join the Cats party for a national theatre tour which culminated in three sold-out nights at Auckland’s Aotea Theatre. The album recorded from that tour, Live in Paradise, peaked at No.6 in the New Zealand charts before going platinum. The 2002 Cats tour featured Harwood’s old friends Eddie Rayner and Noel Crombie and they packed out large, outdoor venues – as they always had.

Harwood and Morris separated in 2002, and she moved to Queenstown. A long-awaited project then followed: for most of her life, Harwood had wanted to record her father’s favourite songs. Recorded at RNZ’s Helen Young studio in Auckland by Andre Upston, Soothe Me was an album of big-band favourites pared back to Harwood’s voice, accompanied by Stephen Small’s piano, and bass and drums. It was released in 2004 by EMI.

Since 2005 Harwood has added music lecturer (at the University of Auckland) and mentor to her CV. In 2006 she formed Debbie Harwood and the Band of Gold, and was a finalist in the best female artist category of the New Zealand Music Awards.

Then, years of struggling with an un-named health issue that left her breathless led to Harwood receiving open-heart surgery at Christchurch Hospital in 2009. “I didn’t really fully recover,” she says. “I had already booked a series of shows at the SkyCity theatre before I had to have emergency surgery, so I couldn’t cancel the gigs because I’d already invested in them. When I stood on that stage I couldn’t walk. It was so hard – I was eight weeks out of major heart surgery – gawd!”

The shows were called Give it a Girl, a residency at Auckland’s SkyCity theatre featuring a top line-up of singer/songwriters including Sharon O’Neill, Shona Laing, Julia Deans, Annie Crummer, Margaret Urlich and Lisa Crawley.

In 2016 she performed alongside Shona Laing, Sharon O’Neill and Hammond Gamble in a national tour of churches and cathedrals.

Harwood’s career has all been down to passion and application; her motivation has been “the songs and the singing. The fact that people like what I do and turn up to hear me has always been a result of what I do, and not the reason why I do it.” She describes herself as a natural introvert (“believe it or not”), who has never really got used to being on a stage. “I still get horrific performance anxiety, but once the music lifts off I’m away.”

Harwood describes herself as a natural introvert (“believe it or not”).

She is still performing with her band Debbie Harwood & the Band of Gold but continuing heart issues since February 2017 have restricted what she is able to do. “I’m working with cardiologists at the moment to try to improve my quality of life but it’s been a long and hard struggle. The heart surgery in 2009 caused other problems which have gradually worn the heart down.”

The determination to keep singing remains. With her band, she performs many of her own songs, which she has begun to record. “I still believe I haven’t quite done what I’ve wanted to do, yet,” she says. Among the remaining goals is to record an album of her originals, producing herself and “with the players I love. It’s happening right now. If I can’t do the big live shows anymore I will do some recording in the lovely sanctuary of a studio. That’s the plan.”

--

Read: Debbie Harwood on New Zealand women songwriters in the 1980s, and how that changed (2010).