“The first inkling I had of it was in 1980, I think,” Rod Coe recalled. “I was in England and I thought I’d go and check out Abbey Road, and someone said to me, ‘Oh, Rod Coe. You’re the guy that did The Saints’ album.’ I thought, ‘Someone in England knows my name!’ It was incredible.”

Bass player Coe scored a job at EMI Australia on the recommendation of a mate just a year after leaving New Zealand following the break-up of his band The Revival, who had a top 20 hit with ‘Viva Bobby Joe’ late in 1969.

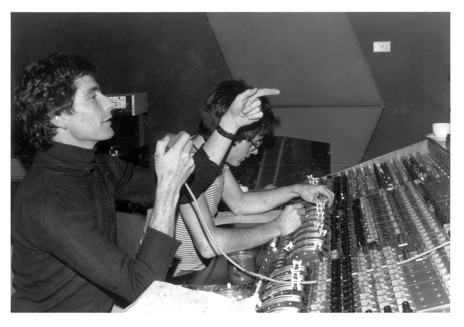

He joined EMI Australia when the EMI Studios on Castlereagh Street in Sydney were still utilising 8-track recording equipment and was there as it transitioned from the Abbey Road 16-track console to a 24-track Studer machine. After the studio was rebuilt in 1978 and renamed Studios 301 he continued to work there as a freelance producer.

He recorded practically every Australian country artist on the EMI roster.

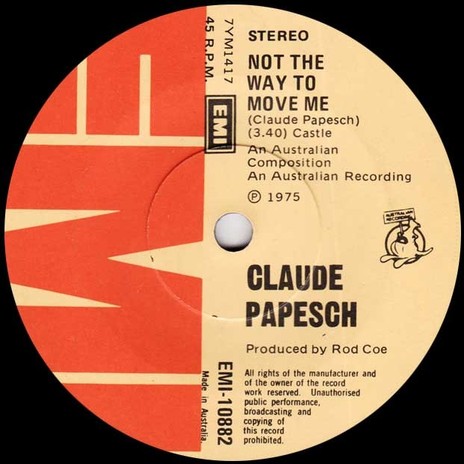

He recorded practically every Australian country artist on the EMI roster including Chad Morgan, Reg Lindsay, Rick and Thel, Anne Kirkpatrick, Jean Stafford and Johnny Ashcroft as well as New Zealand artists who had made a home in Sydney such as The La De Da’s, The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, Claude Papesch and Mike Rudd. Throughout it all he remained a gigging musician and even toured with international stars Albert Lee and rock and roll’s original poet, Chuck Berry.

Although resident in Australia since 1970, Coe has never sought citizenship. “I’m very proud that I can still call myself a Kiwi,” he said. “Australia’s been very good to me, make no mistake, and I’ve certainly seen a lot more of it than I’ve seen of New Zealand, as it turns out, but still a Kiwi.”

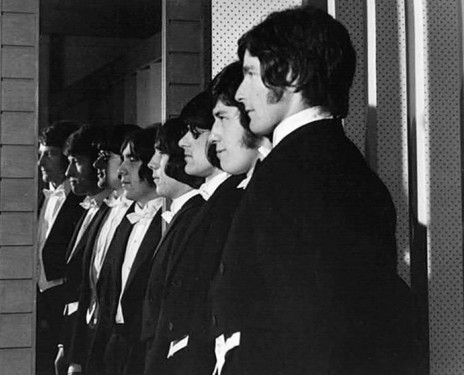

Born in Lincoln, south of Christchurch, in 1945, Rod Coe was brought up on a farm at Coe’s Ford. Apart from a few piano lessons, music had not seriously crossed his mind until he started at St Andrew’s College and joined the choir. At the same time the latest pop music on the Lever Hit Parade was turning him on.

Upon leaving school he began mucking around on guitar and became a cadet with the NZ Broadcasting Service – before it became the Broadcasting Corporation – at Radio 3ZB. When it was discovered a group of workmates also played guitar, Coe switched to bass and they formed a band.

A year later he moved in to television at CHTV3 working alongside men like John Lye and Peter Muxlow, who would go on to long careers behind the scenes on the tube. By night he continued playing in bands, one of the more serious early ones was The Avon City Jazz Band.

In 1966, Coe took a year’s unpaid leave to have a look at Australia and ended up in soul band The Hallelujah Chorus, soon shortened to The Chorus, for a residency at John’s and Charlie’s above The Bourbon and Beefsteak in Kings Cross, Sydney.

“I lived in the Cross and we had Friday and Saturday nights playing up there,” Coe recalled. “There was a lot of action going on in those days because Sydney was full of US servicemen on R&R from the Vietnam War.”

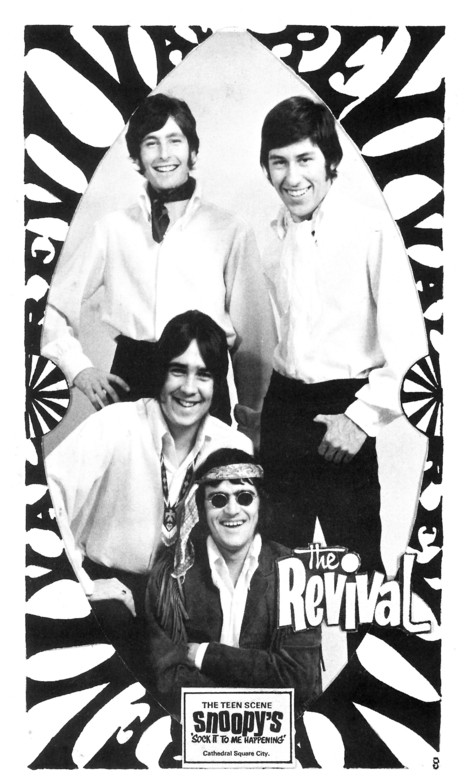

Returning to his job at CHTV3, the experience of playing in Kings Cross led to him joining guitarist and vocalist Eddie Hansen, organist Robbie Carpenter and drummer Bruno Berens in The Revival, who had earlier been known as The Blues Revival and Zeppelin Revival.

They played a repertoire of top 40 covers at the Stage Door in a Hereford Street basement, as well as working for promoter Trevor Spitz at Snoopy’s in Chancery Lane. A steady stream of touring bands from Wellington and Auckland kept them up to date with what was happening in the rest of the country.

The Revival won the Christchurch heat of the Battle of the Bands early in 1969 but didn’t fare well in the national final, won by Upper Hutt’s Cellophane, at the Auckland YMCA that May.

But by then The Revival had come to the attention of HMV producer Peter Dawkins, fresh from the chart-topping success of Shane’s ‘St Paul’ after just a few months in his new job. Dawkins got word to the band’s manager Trevor Spitz that he had a song for them to record but they needed to find a singer. Dawkins suggested Craig Scott from Fantasy, another band he had had his eye on.

“We’d seen Craig singing in Dunedin, when we’d been down there, and thought he was pretty good, and Craig was keen on the idea,” Coe said. “So we went up to Wellington and recorded it and, lo and behold, it did alright.” The song was the Eddy Grant-penned ‘Viva Bobby Joe’, a UK top 10 hit for his band The Equals.

Working in the studio with Dawkins was a revelation for Rod Coe.

Working in the studio with Dawkins was a revelation for Rod Coe. “He was fantastic even back then. He knew exactly what he was doing. He persevered. You know, like, we were raw; we just didn’t have much idea about how to go about things. He just had the magic touch. He knew how to make it sound good, he knew how to just work the band to the point where we came up with a really good performance.”

Despite the fact ‘Viva Bobby Joe’ was getting airplay and had entered the charts, The Revival didn’t hit the road, but remained at their Christchurch residencies. Dawkins offered the band another song as a follow-up, but none of them liked it. “I don’t even remember what it was called,” Coe laughed.

By the time ‘Viva Bobby Joe’ peaked at No.14 on the NZ charts in December, The Revival split up after a Christmas gig at Mt Maunganui. Craig Scott went on to huge success as a solo artist, helped by a resident spot on TV show Happen Inn, while Eddie Hansen became a New Zealand guitar hero in Ticket.

Coe and Revival drummer Bruno Berens kept hold of the Snoopy’s residency with new band Axle Orchestra, featuring guitarist Bob Heinz and jazz saxophonists Stu Buchanan and Pete Davey. The band lasted nine months until Coe was married and the newlyweds decided to try their luck in Sydney.

“I just wanted to get out of Christchurch,” Coe said. “I just felt that I could make a living out of making music. I was restless, I suppose, more than anything else.”

In Sydney he put in calls to contacts from his Kings Cross days and hooked up with songwriter Greg Quill in his band Country Radio, which was evolving from an acoustic trio to an electric line-up. They recruited Coe and Bruno Berens as their rhythm section, but Coe took off after three gigs when he was invited to join established band Freshwater.

Led by guitarist Murray Partridge, Freshwater had formed in Wellington in 1968 and decamped across the Tasman Sea. They had released 45s on Australian independent labels W&G and Caesar’s International before being joined by Sydney singer Alison MacCallum and Coe for the RCA Victor single ‘I Ain’t Got The Time’ in late 1971.

In the meantime, Coe had found his dream job as a house producer at EMI Studios. Former NZ television workmate and songwriter Wayne Thomas (now known as G. Wayne Thomas) had become friends with EMI Australia managing director Ken East and when the company lost Mike Perjanik and another producer in quick succession, Thomas put in a good word for Rod Coe.

“That got me an interview and, much to my surprise, I got the job with no experience whatsoever other than what I’d been doing in television, which was technical production and technical direction. And because I’d been playing for so long and had good contacts in Australia, that was in my favour too, I guess.”

EMI had a huge local roster encompassing operatic singers, pipe bands, classical trios, country acts and pop and rock artists and Coe was called on to produce it all. His first job was to re-record the vocal with a different singer for a single from an Australian production of Godspell.

A few months later, EMI Australia poached Peter Dawkins from HMV in Wellington as their head of A&R. “That was great,” Coe remembered. “It was lovely because, you know, having worked with Pete I knew how good he was and I knew that that would take the pressure off me and allow me to learn a bit.”

During the first half of the 1970s, Coe produced records for Terry Hannagan, US singer-songwriter Karl Erikson, The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, Carson (who included Wanganui’s Mal Logan), Mike Rudd’s Ariel, Hammond organist Claude Papesch, Mike McClellan and even The La De Da’s.

In Peter Dawkins’ 2008 book The Icecream Boy, published by Parkinson’s NSW, he recounted a meeting between himself, Coe, The La De Da’s and their road manager Michael Chugg during initial sessions for their Rock And Roll Sandwich LP where the drummer Keith Barber complained, “It’s my drums. I imagined they would sound purple and they’re green.”

“Yeah, I remember Keith Barber was not happy,” Coe recalled. “He didn’t like his drum sounds at all in the studio.” Recording was scrapped and the band decided they should record live at Doncaster Theatre in Kensington. Coe set up a mobile recorder backstage capturing the band as if playing a gig, and overdubs were added later in the studio.

“They got what they wanted in the end. I guess I was still pretty inexperienced at that stage and I didn’t really know how to get what they wanted in the studio, you know, so we just went with what they wanted and it worked out.”

As well as his production responsibilities, Coe was called on to play bass in various sessions as well. He played on the soundtrack LP of the Crystal Voyager surf movie, Jon English’s ‘Turn The Page’ single and Shona Laing’s second album Shooting Stars Are Only Seen At Night – all produced by Wayne Thomas, the latter with Bruno Lawrence on drums.

“I was doing quite a few sessions at that stage, and the guy who was musical director for Jesus Christ Superstar, Patrick Flynn, he used to get an awful lot of sessions for commercials. He was a good arranger and I used to do quite a bit of work for him in those days.”

Coe wasn’t a competent music reader, but Flynn would give him a chart an hour before the session so he could get a good look at it and encouraged him to sit down on the job with the quick-reading club band heavyweights and look like he was following the chart.

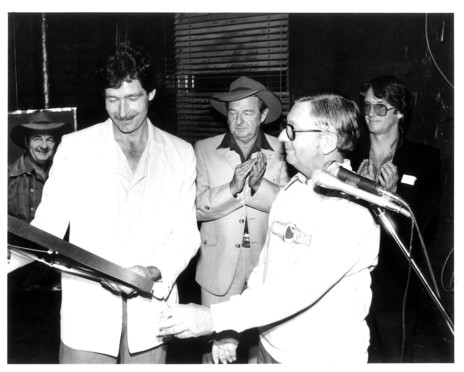

He also played bass on a couple of tracks on Australian country music icon and EMI institution Slim Dusty’s 1975 LP Lights On The Hill, produced by Peter Dawkins. Dawkins revealed in The Icecream Boy that it was an album that almost got him fired.

By that time Slim had already released over 50 albums for the company, and after producing two bush ballad LPs for him Dawkins saw the opportunity to get a bit more adventurous with the truck record Lights On The Hill. When he began double-tracking guitars and violins and adding truck noises, Slim took his concerns to the general manager. Producer and artist reached an impasse and became firm friends and the album went on to become Slim’s best-selling to that point.

When Dawkins announced later in the year that he was leaving EMI for Festival Records, Slim was the sole artist who went to the EMI bosses and asked what they were going to do about his leaving. Before he went Dawkins revealed to Slim he thought Rod Coe should be his new producer.

“Pete recommended to Slim that I take over,” Coe said. “Because he knew, you know, the type of person, I suppose, that Slim wanted, and that was someone that wouldn’t clash heads with him all the time. So, it worked out really well.”

The first LP Coe produced for Slim was a return to the bush ballad style Things I See Around Me. There was an instant rapport and Coe would produce every Slim Dusty recording from there on in – close to 40 albums until Slim’s death in September 2003 at the age of 76 after battling lung and kidney cancer.

“The production job (with Slim) wasn’t taking raw material and turning it into something, it was really just maintaining a status, as much as anything else. He knew exactly what he was doing; he knew what it was all about. He knew what songs to get for his audience.

“So, in a lot of ways that was a big learning curve for me because I thought I knew what a good vocal was and what was a good take and all that sort of stuff, but Slim taught me heaps more about all that because he just knew.

Throughout his career as a producer, Coe continued as a gigging bass player.

“It’s about conveying emotion more than anything else and it wasn’t about being technically good or being fantastically consistent in terms of tone or volume throughout a track. All of those things that you were concerned about in pop records didn’t apply to Slim. It was really about performance and selling the message and he knew what connected.”

After the first album was released, Coe bundled his wife and two sons into a second-hand VW Kombi and followed Slim’s tour into North Queensland for four weeks to have a look at Slim on the road and gauge his audience.

Throughout his career as a producer, Coe continued as a gigging bass player. He was part of The Doug Parkinson Band with drummer Bruno Lawrence for a residency at the Grange Restaurant in the mid-1970s and then joined old Christchurch guitarist mate Chris Piper’s band The Mangrove Boogie Kings when they arrived in Sydney from the Hawkesbury minus their bass player.

When The Mangrove Boogie Kings heard Chuck Berry was coming to Australia for two shows they put together a demo tape and sent it off to the promoters hoping to score the backing band spot. “They decided that we were the right band for the job and we got the tour. But we also had to sign a recording contract with them, which wasn’t such a good idea,” Coe laughed.

Unfortunately for Coe, Chuck Berry brought his own bass player with him, so Coe could only watch from the wings for the first show in Sydney. “We got to the Melbourne show and I decided that I wasn’t gonna let this opportunity pass and I’d go on stage too and play as well. But I didn’t plug into any amp or anything, I just got on stage and just played,” he said. “Just so I could say I’d been on stage with Chuck Berry. You wouldn’t miss an opportunity like that, would you?”

All mad Chuck Berry fans, the band didn’t have much to do with the star, and when he came into their dressing-room before the show in Melbourne and just stood there, the band members were dumbstruck. After a few moments of silence, Berry turned on his heel and walked out.

“The Mangrove Boogie Kings were a high-energy band in a sort of a punk tradition more than a blues, rock and roll band. It wasn’t a highly technical band by any means, it was just people having a good time. But as far as I remember it was no rehearsal, it was just get up and play.

“We’d been used to playing all these Chuck Berry songs, but at completely different tempos to the tempos that Chuck Berry did them on stage. So he’d count things in and immediately The Mangrove Boogie Kings would sort of go up to their normal tempo, so there was a bit of tension; just the foot would come down hard and go, ‘This is where it is,’ and you’d just sort of have to get with it.”

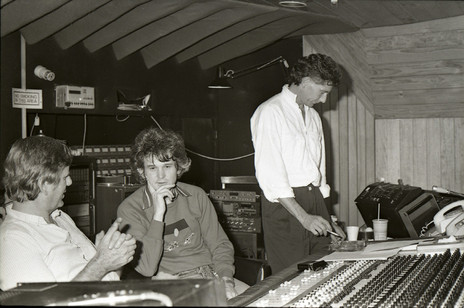

The production for which Coe was probably best known came via instruction from EMI in the UK in late 1976. Brisbane punk band The Saints had booked a three-hour session at Window Studio in Brisbane and recorded their song ‘(I’m) Stranded’ with engineer Mark Moffatt. They pressed 500 singles on their own Fatal Records and one of them found its way to influential BBC broadcaster John Peel who named it one of the best singles of the year. Sounds magazine went even further, labelling it “single of this week and every week”.

The 45 had gone largely unnoticed in Australia and it was a total surprise when EMI in the UK sent word that EMI Australia were to sign The Saints to a three-album deal. “So, I was the man in the seat and away I went,” Coe said.

He was dispatched to the concrete block Window Studio in Brisbane’s West End for two days where the rebellious, anti-authoritarian Saints met him with indifference. Coe remembered singer Chris Bailey summing it up best in a later anecdote when he said something like, “This silk bomber jacket and briefcase turned up.”

Faced with the daunting situation of an inexperienced engineer and a room and gear he was unfamiliar with, Coe’s plan was to make the songs sound as close to Mark Moffatt’s single as he could. “I came nowhere near it really. But it sort of suited my style, where I’d just basically record what’s going on and just try and keep the vibe good and encouragement. You know, it’s not about deep detail or anything like that; it’s not about musicianship. It’s about energy.

“At the time I kept thinking, ‘Well, this is a really rough thing,’ but I loved the idea of the whole punk thing, which was just starting to happen. And I loved the anti-establishment vibe of it and the fact that anyone could pick up an instrument and communicate just as well as some slick 10-part harmony thing that’s like pop heaven.

“The big thing about Australian punk was that people just weren’t so much into the fashion. I mean punk in England was such a fashion business. There was some good music came out of it, but, you know, that was the entrée for a lot of people, because it allowed you to dress up a certain way. The Saints weren’t into that at all.”

(I’m) Stranded was released in February 1977, but later in the year when EMI Australia was restructured Rod Coe was let go with a freelance deal that he would continue producing Slim Dusty’s two albums per year as well as one other each year.

However, the freelance work amounted to very little. “I was typecast at that stage,” Coe said. “I was getting a lot of offers from people who wanted to be Slim Dusty, but not much else outside of that.”

By the late 1980s Coe was in pub covers band The Dan Johnson Band, who for a short time also included former Dragon guitarist Robert Taylor and twice toured in Australia with English-born former Emmylou Harris and Everly Brothers guitarist Albert Lee.

Coe had undertaken a couple of shorter tours as bass player and tour manager with Slim Dusty at the end of the 1970s, but in 1987 he joined Slim’s band for a six-month run of shows in Sydney and the next year became the permanent bass player and bandleader in Slim’s Travelling Country Band until Slim’s death in 2003.

At the end of that year Coe left Sydney and spent five or so years in the Hunter Valley before heading to Northern New South Wales where he now resides in New Brighton. He’s back to being a freelance bass player with all manner of bands and has recently toured with Slim Dusty’s daughter Anne Kirkpatrick.

He doesn’t miss producing at all. “It’s a digital world and I’m just not up with it. It would be like a dinosaur going into a studio. I felt incredibly lucky to have had that job at EMI and to have had the career I’ve had because it fell in my lap in a lot of ways. I was there at the right place at the right time.”