AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

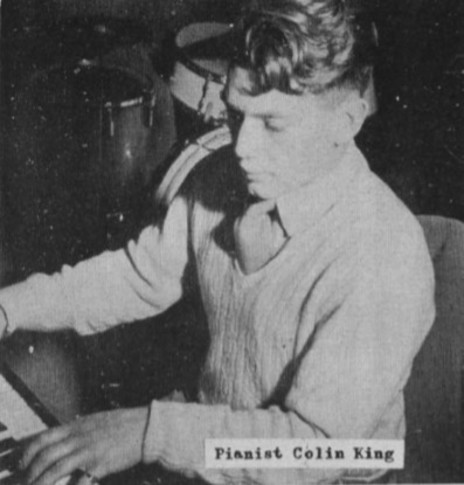

Colin King

Now a lively octogenarian pianist and dance-band leader who still performs, mostly at retirement homes and for charity events, King once ran the province’s leading dances, was a music store owner and a promoter.

Fond of referring to himself in the third person, he says, “Colin had Taranaki’s top band for a good 10-12 years until rock’n’roll started to kill it. We played almost every night, from Waitara to Waverley, six-seven nights a week. I was a professional musician all of my working life, and I’m still doing it …”

King was born in 1935 in the New Plymouth suburb of Fitzroy, the eldest of four children; when he was seven years old the family shifted to Brixton and, later, Waitara – the Taranaki town where he still lives. His mother, a pianist, had him tinkling from a young age. “I spent five years receiving musical tuition at the convent in Waitara, which I hated: nuns rapping me over the knuckles. I hated classical music too; my inspirations were Nat King Cole and Louis Armstrong.”

When he reached his teens, King began piano lessons with Hazel Davies, wife of Taranaki band leader Leo Davies. King credits Hazel with teaching him the rudiments of rhythm. He left school in 1950 to serve a mechanic’s apprenticeship. It lasted three months. “I formed my first band, a trio, and started playing all over Taranaki. I was earning more money with that than with my day job, so I quit and I’ve been a professional musician ever since – apart from my music and record shops, which were only ever a sideline really.”

The trio evolved into Colin King and the Harmonisers, generally an eight-piece line-up; the original personnel included King’s schoolmates Bob Crowe, Keith Kramer and Dennis Taylor, who provided the nucleus during the early years.

ON A SATURDAY IN 1950S TARANAKI, “THERE’D BE 15 DANCE HALLS AND DANCE BANDS PLAYING ON A SATURDAY NIGHT.”

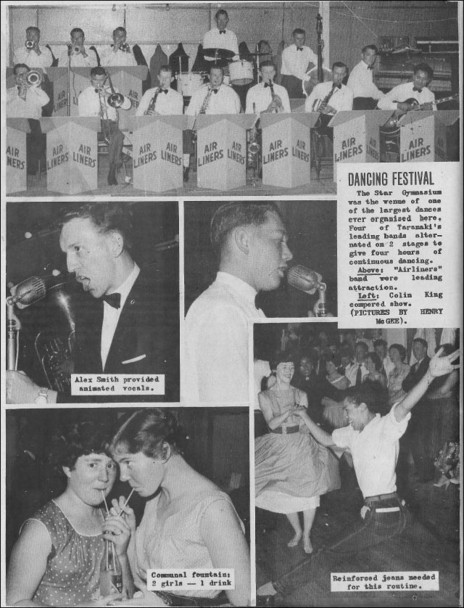

When Colin King and the Harmonisers arrived on the scene in the 1950s, Taranaki had a bustling nightlife, which became even busier as the decade progressed. King recalls: “You could pick up a paper and on a Saturday there’d be 15 dance halls and dance bands playing on a Saturday night. You had your choice of going to them, now you have none.”

In 2007, King’s friend, Taranaki crooner Monty Julian, told Chris Bourke, “I was the MC and vocalist with The Modernaires which in those days, the early-1950s, was the Taranaki band. The Modernaires had started the Agricultural Hall – “The Agri” – which had become the Taranaki dance venue, but then a young guy called Colin King came along and started dances at the Star Gym and the Stratford War Memorial Hall, and it proved how popular we had been.

“It was the end of an era for us, the type of music we played, and overnight it was just Colin from then. Colin just hit the nail on the head and that was it.” Later in the decade, Julian and King went into the music/record store business together; inevitably, Julian also served as the Harmonisers’ MC and occasional vocalist.

The rise of Colin King and the Harmonisers was indeed swift, not least due to King’s business nous. Rather than compete directly with his peers to perform at the established dance halls, he created his own regular dances, initially in conjunction with the regional councils or the venue owners, the bowling and tennis clubs, some weekly affairs, others fortnightly or monthly. Colin King and the Harmonisers played every town in Taranaki, not just the main centres but Mokau, Rahotu, Kaponga …

Not that the Harmonisers ever had the field to themselves. By 1956 there were over a dozen dances to choose from in Taranaki on a Saturday night. Other local bands included the Airliners, the Ambassadors, the Melodians Orchestra, Tommy McArthur and His Band and the Nu Tones. None, though, had a calendar as busy as Colin King.

“Let’s see … we did Tuesday night at the Fitzroy Ballroom for eight years and we would always have six or seven hundred people.” On a Tuesday night? “Sure, on a Tuesday night. And we might do Rahotu or Kaponga on a Wednesday and get two or three hundred people. There was no television, of course, so if you went out it was either to the pictures or to a dance hall. Friday nights for a long time we played the New Plymouth Trades Hall and Sundays at the Overseas Club.

“But our big one was in Stratford, which I ran every fortnight. Stratford is the most central of the Taranaki towns so I’d arrange buses from every town in Taranaki – Hawera, Waitara, New Plymouth, Opunake, Waverley – and the place would be packed. Saturday nights we’d play either Stratford or the Star Gym in New Plymouth and we did that for 20 years. Some nights we’d have 1500-2000 people, and never less than 1000.”

In The small Dance halls, “The piano would have half the hammers off it because the rats had eaten them.”

There were huge contrasts between the venues, King recalled in 2007. The smallest hall he played in was at Ahititi, at the bottom of Mt Messenger: a tiny place he compares to a living room. There was no power, and gas lighting that kept going dim. The tiny stage had “just enough for one fellow and a piano. The piano would have half the hammers off it because the rats had eaten them. Around the halls, the pianos didn’t get looked after at all, the rats got in and strings were broken, no ivory on the keyboards. And then you’d perhaps go and play somewhere where there’s a big grand piano, at the nurses’ home in the hospital in New Plymouth.

“You’d get out there and you’d play, play, play – and you might only have two or three couples on, because the fellas would be outside, boozing. But then about 10, 11 o’clock they’d start coming in and so, instead of finishing at midnight, you’d have to play to one o’clock, two, three o’clock in the morning. And you’d still be out there playing music, because they’d been boozing up outside, and then they’d come back wanting to dance all night.”

To keep up with the latest hits, King purchased musical arrangements from Sydney and Auckland, adding three or four new numbers to the band’s repertoire every month. It was strictly old school, the evening’s music bracketed into genres and dance styles, the foxtrot and Gay Gordons, the jitterbug. There were occasional theme nights. Supper was generally provided as part of the ticket price (between four and six shillings); otherwise, snacks and refreshments were available for sale, cigarettes too; no pass-outs to deter the car park drinkers.

Although he survived the first wave, rock’n’roll was to have a drastic effect on King’s career. In 1956 the winners of a talent quest organised by King at Waitara’s Theatre Royale was a just-formed group named the Be Bops, who performed Gene Vincent’s ‘Be Bop A Lula’. Rock’n’roll had arrived in Taranaki.

King claims to be the first promoter to bill Johnny Devlin as “New Zealand’s Elvis Presley”

“What do I like about rock’n’roll? Nothing!,” he says, with little humour but no rancour. “I hate the guitar. I hated it then and I hate it now. Electric guitars, acoustic guitars, all guitars! I like trumpets and saxophones and trombones. Elvis Presley took that away from me.”

Despite these sentiments, many younger Taranaki musicians cite King as a mentor, including guitarists, and he increasingly shared the bill with the guitar bands he hired as rock’n’roll took hold.

In 1957 an acquaintance told him about a Whanganui youngster making waves, performing nothing but Elvis Presley songs. King decided to give the young man a guest spot at the Stratford dance and lays claims to be the first promoter to bill Johnny Devlin as “New Zealand’s Elvis Presley”.

King remembers it well: “Colin put out posters and Colin advertised it in the papers. New Zealand’s Elvis Presley! I was setting up the hall, around 5pm I suppose, and young Johnny Devlin phones the hall to say that he can’t make it, he was stuck somewhere down the island, it was raining and he was travelling by motorbike. I said, ‘if you’re not here by nine o’clock tonight, I’ll sue you.’ I’d spent all of this money, see? Advertising New Zealand’s Elvis Presley.

“He turned up just before nine, on his motorbike, guitar strung across his back, and he just got up and started jumping around the stage, rolling in the dust, wearing a powder blue jacket. I’ll never forget it. We became good friends.”

Indeed they did. That year King opened Colin King’s Music Centre in Waitara and two years later he went into partnership with Monty Julian and opened a second store in New Plymouth, The Record Inn. The guest performer at the opening of The Record Inn was Johnny Devlin, by then a superstar.

Ronald Hugh Morrieson “was a good bass player ... if you could keep him off the grog.”

Other recording stars who appeared at the store or on the bill with the Harmonisers included the Keil Isles, Ricky May, Jim McNaught, the Howard Morrison Quartet, Peter Posa, and Paul Walden. The stores sponsored shows on New Plymouth’s Radio 2XP, including The Taranaki Popularity Parade, a chart-type show, voting forms available from the two stores.

Colin King’s Music Centre specialised in selling record players, which was the store’s main earn, and providing stereograms as prizes at the dances was a further incentive for the punters. Despite the advent of rock’n’roll, Colin King and the Harmonisers were still hanging in.

King may have been a big fish in a small pond but he was certainly well-connected. Few national and international performers passed through Taranaki without an introduction and – when King and his mates flew to Auckland to see his musical hero Louis Armstrong in concert – promoter Harry M Miller organised a backstage meeting.

By then, 1963, the best-selling appliance at Colin King’s Music Centre was no longer the stereogram but the television (New Zealand transmissions began in June 1960). The irony wasn’t lost on King: “I was the killer of my own career.” The weekday dance, King’s cream for so many years, was the first casualty. And then came the Beatles. More guitar groups! One more nail for the dance bands.

Still, the Harmonisers survived for a few more years. A young Taranaki journalist, Lew Pryme, began his musical career under King’s guidance, and Hawera writer Ronald Hugh Morrieson (Came a Hot Friday) played double bass with King for a spell. (“He was a good bass player,” King recalled in 2007, “if you could keep him off the grog. That was his problem.”) The band backed numerous acts who were known nationally. Meanwhile, the television retail business was booming and King opened shops in Inglewood, Eltham and Rahotu.

The Changes to the liquor licensing hours in 1967 continued the decline of the dance halls, both old school and youth-oriented.

Changes to the liquor licensing hours in 1967 continued the decline of the dance halls, both old school and youth-oriented. Gigs may have been fewer for King but he kept his band going through to 1975, when sold his businesses and shifted to Australia. For 20 years he was resident (solo) pianist at the RSL Club in Tweed Heads, a northern New South Wales near the border with Queensland.

On a trip home in 1989 to see his elderly mother, he was persuaded to organize a reunion dance. His mother advised against it. “She said, ‘Don’t you dare. Because the bikies will throw chains through the Stratford hall windows. They’ll smash it up. No, don’t you dare Colin.” But people he ran into kept saying, “ ‘We don’t have the old dances like we used to, Colin’.

“So I thought, bugger it, I’ll give it a go. I expected three or four hundred, following what I was getting at the clubs in New Plymouth, so I thought it was worth a try. So that’s when I advertised that reunion dance. Jacked up my family to help me to do the door, the coffee bar. And I invited all musicians who had ever played with Colin King over the 50 years, to join me on stage. And that’s when Robin Ruakere and Lew [Pryme] was coming and there were 19 of us on stage.

“I’d said to the musicians, the booze is on me till eight o’clock, we start at seven. So we’re out the back room, and we had $400 worth of spirits, and beer in an hour: all the musos hadn’t seen each other for years. And the family came to me and said, ‘Hey Dad come and look at this ...’

“They took me out to the exit door, and the Stratford Memorial Hall has a huge parking area outside. They were four deep, queued, like a snake, all over this carpark and down, waiting to get in, and we weren’t opening the doors – like we never used to – till 8 o’clock. At 8 o’clock, 1200 people flowed through. That was a highlight of my life.”

The event was a huge reunion for people who had been dance partners in their youth. “You could see from the stage,” King recalled. “It was ‘Gidday! You married her!?’ They hadn’t seen each other since the dance hall, 30 years prior. ‘I remember you!’ Old girlfriends and boyfriends. ‘Who did you marry?’ It was one big happy party. And you put 1200 into a hall, you’ve got a bloody crowd.”

King returned to Taranaki permanently in 2000, settled back in Waitara, and still plays whenever an opportunity arises.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air