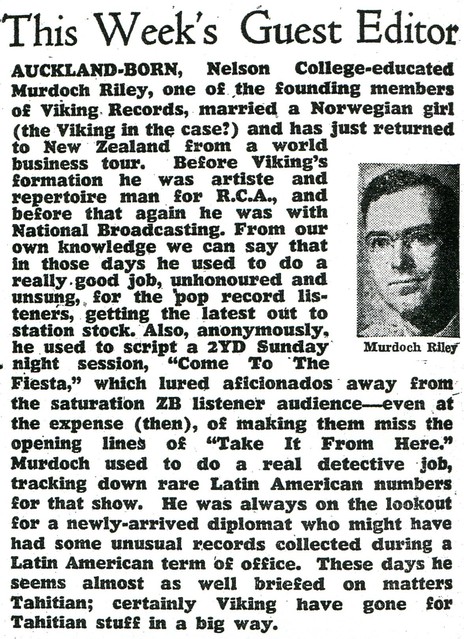

Riley joined Broadcasting straight from school in 1945. He already had a wide knowledge of music and began working in programming at 2ZB and head office. At ZB he programmed a new releases show for Sunday afternoons, using discs airmailed out from the US (he recalled “shocking the natives” by playing some R&B off the Chess label). For 2YD he shared his love of Latin-American music by scripting the programme Come to the Fiesta, approaching diplomats from South America for the latest hits. For the ZBs he supplied discs to Selwyn Toogood for use on the hugely popular Lever Hit Parade, the weekly pop show which was listened to religiously around the country. Riley’s broad awareness of music led to him being appointed “the purchasing officer for everything – classical and popular music – for the whole country.”

Scheduling the Lever Hit Parade was especially influential, and sometimes he found himself having to pick between the overseas original and a local take on a song.

Scheduling the Lever Hit Parade was especially influential, and sometimes he found himself having to pick between the overseas original and a local take on a song. The original was usually the hit, so it would get preference – but he would occasionally slip in the local cover. “You couldn’t really deny the top version entirely, the whole time,” Riley told me in 2007. It was a balancing act. As part of the public service, the NZBS was determined to be above board, and to avoid being used by private companies for commercial promotions. Among the staff there was also the desire to be fair to local releases, but not to the extent of damaging the programme through playing inferior cover versions. “Musically, if I could possibly promote local artists, I’d do so.”

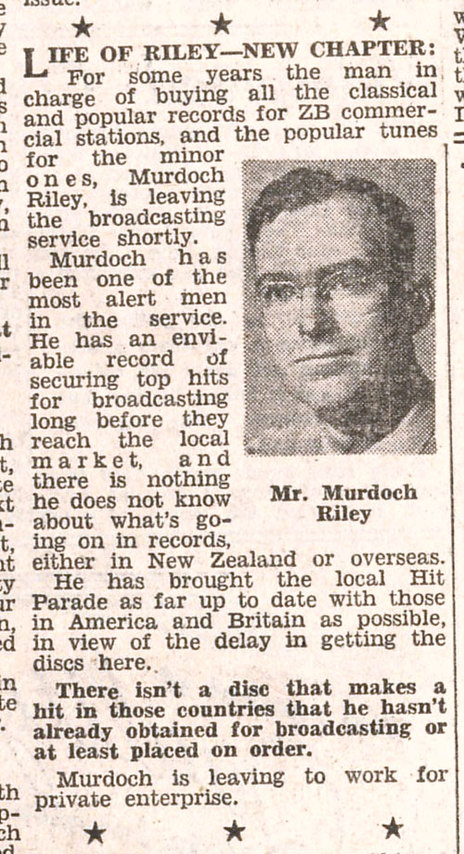

Riley got the opportunity to become more closely involved with local musicians when he left Broadcasting in late 1954 to join “private enterprise” – Tanza Records. At the time, Truth paid tribute to him: “Murdoch has been one of the most alert men in the service. He has an enviable record of securing top hits for broadcasting long before they reach the local market … He has brought the local Hit Parade as far up to date with those in America and Britain as possible, in view of the delay in getting the discs here.”

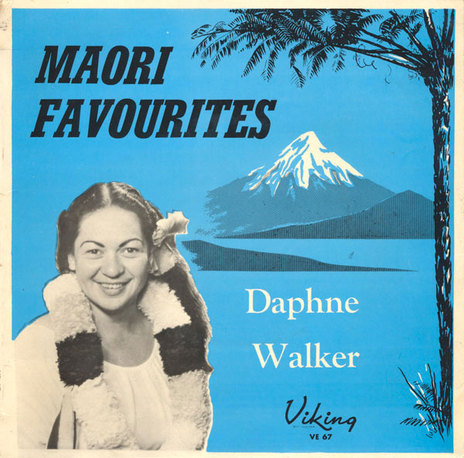

Early in his stint at Tanza, he encouraged Bill Wolfgramm and Daphne Walker to build on the success of their 1954 hit ‘Haere Mai (Everything is Kapai)’ by recording more locally written songs, especially with Māori or Polynesian content. “I was looking at the success of ‘Blue Smoke’ and thinking to myself, well let’s see if we can duplicate something like that.” Walker wasn’t keen – she preferred familiar material – and neither was Sam Freedman, the writer of ‘Haere Mai’. But the policy was successful, not just with ‘When My Wahine Does the Poi’ but later with full albums of Māori and Polynesian albums by Walker and others. “When I look back at those lyrics, I can understand why they didn’t like to use some of those songs,” said Riley. “They were pretty corny lyrics. But the melodies were good.”

‘Haere Mai’ sold “not less than 40,000 copies,” Riley recalled. It was at a time when supply of any records was difficult, thanks to restrictions on imports and the use of overseas funds. But the song was also an actual hit, not hyped by the record company and requested often by radio listeners. “People genuinely wanted to hear them,” he told Gordon Spittle in 1992.

At both Tanza and Viking, he remembered how popular Hawaiian and country and western songs were on the radio request sessions.

At both Tanza and Viking, he remembered how popular Hawaiian and country and western songs were on the radio request sessions – outside of mainstream pop – and this was reflected in the artists he released. It gave the labels a “good, safe base” for their catalogues.

The biggest hit he was involved with almost didn’t happen. Crombie Murdoch wrote ‘Opo the Crazy Dolphin’ as an affectionate shout-out to a dolphin that regularly greeted holiday makers at Opononi in the far north, and Pat McMinn was recruited to sing the jaunty song. Unfortunately, just as the disc was about to be released, Opo died in mysterious circumstances. It says a lot about how attitudes have changed that Riley was at first reluctant to exploit the national mourning that took place, and was tempted not to release the disc. “It seemed to be the right thing at the end of it, but at the time we thought, God, can we really release this recording?”

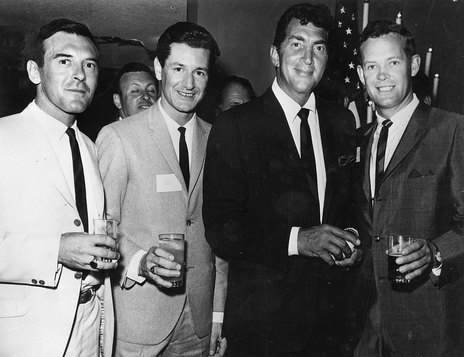

Tanza was not in good shape when Riley arrived there in late 1954; he could feel the parent company, Radio Corporation of NZ, losing interest, and in 1955 the label lost its lucrative distributorship of Capitol to its arch-rival, HMV. This created an awkward moment when Nat “King” Cole, a Capitol artist and director, visited New Zealand. At Whenuapai Airport in Auckland, Tanza founder Bart Fortune greeted Cole, who sheepishly apologised for being the “bearer of bad tidings”. Standing alongside Fortune was HMV’s managing director, Jack Wyness.

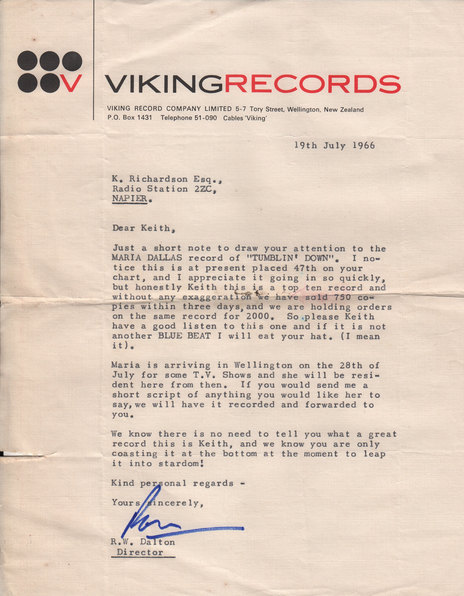

Riley was aware that Tanza was struggling, and eventually he thought, “Why am I doing all this for somebody else? I may as well get out and do something myself.” He founded Viking Records in 1957 with two partners, Jim Staples and Ron Dalton. The pair were travelling salesmen for Autocrat car radios, which meant they had networks of shops around the country.

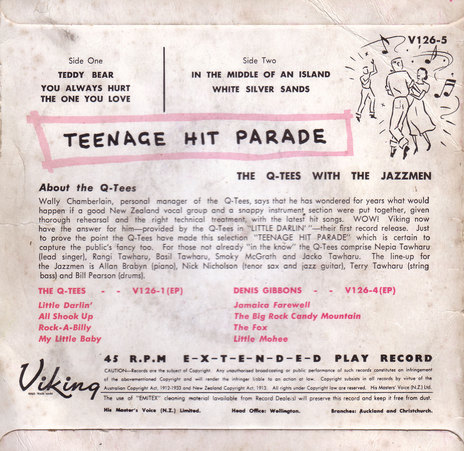

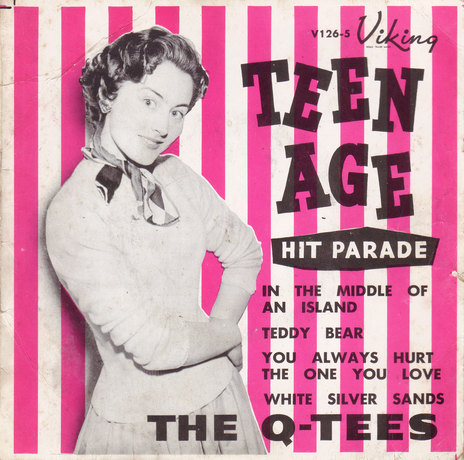

Viking’s first release came out in October 1957: Little Darlin’, an EP of rock and roll songs by Manawatu group The Q-Tees.

Viking’s first release came out in October 1957: Little Darlin’, an EP of rock and roll songs by Manawatu group The Q-Tees. Recorded by 2ZA announcer Wally Chamberlain in Palmerston North, the EP sold 1,000 copies in its first 10 months. Shortly afterwards, the label released a 10-inch LP by Cole Wilson, lead singer of The Tumbleweeds. Country Songs, Vol 1 sold 2,000 copies in a year.

Viking spent its first year battling a difficult economy; 1958 was the year of the notorious “Black Budget”. The partners weathered this by taking day jobs and working on Viking after hours. They also secured the distribution rights for several small overseas labels. One of these labels, Canada’s Oriole, soon had a hit with ‘Clap Your Hands’ by the Beau Marks. Viking sold 30,000 copies in Australasia and the proceeds paid the bills for a couple of years. Another release, ‘Chulu Chulu’ by Eddie Lund – an American bandleader in Tahiti – sold 10,000 copies in 1958 alone. Although the 78rpm format was being phased out, ‘Chulu’ was released on 78 because they still sold well around the Pacific.

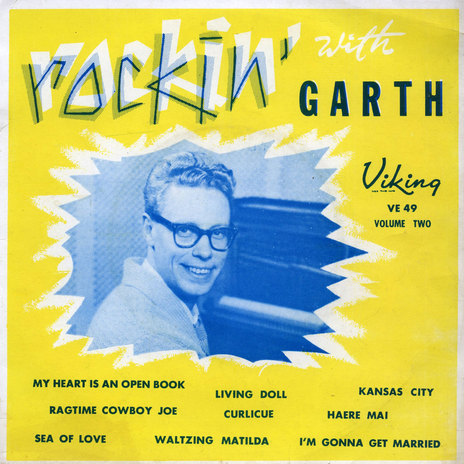

Despite the hurdles, Viking continued to record and release local artists – many discs by the Wellington pianist Garth Young, plus more by Cole Wilson. In late 1959 the label found its first local star. Ronnie Sundin’s single ‘Sea of Love’ was released in September that year, and sold 15,000 copies in just four months.

Wellington recordings were done by hiring HMV’s studio, though never on a Sunday because HMV’s Wyness – a Seventh Day Adventist – didn’t approve. Riley did manage to book the studio one Sunday to record Young’s Rocking Piano EP, as the pianist was unavailable at other times because of his commitments at the Pines Cabaret. But – before Young had played a note – Wyness entered the room and insisted they stop. “So we had to drag out this grand piano we’d hired, and we recorded it on an old piano out at the Pines,” said Riley. “Nimmo’s the music shop wasn’t too impressed.”

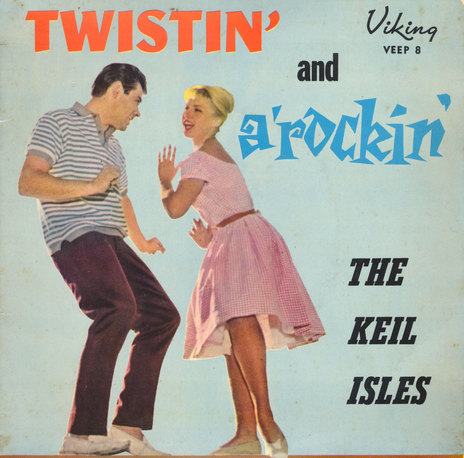

Viking’s golden period was the early to mid-1960s, when Ron Dalton handled the A&R out of Auckland. The company provided him with a shortwave radio to tune in to the American hit parades, see what was selling, and tape them for possible cover versions. The biggest success came with ‘The Twist’, after public radio decided not to play Chubby Checker’s original because it was too raw. Viking recorded The Keil Isles performing the song, which got plenty of radio play just as the Twist craze took hold, and their version became the local hit.

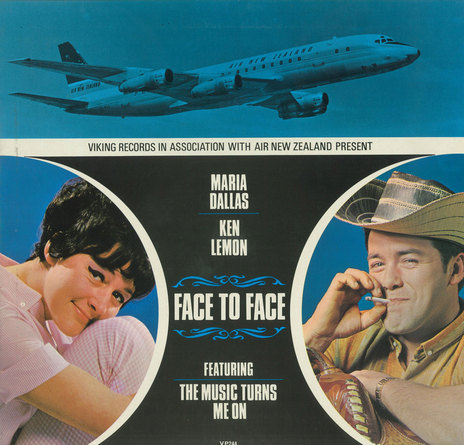

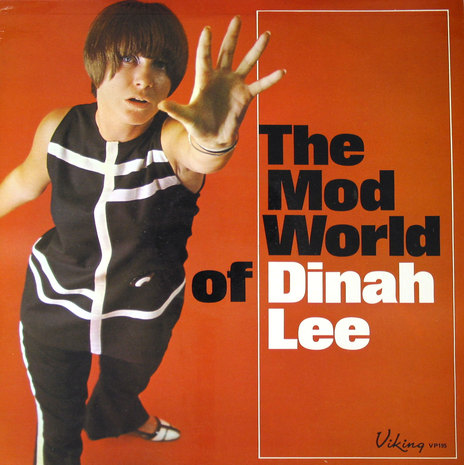

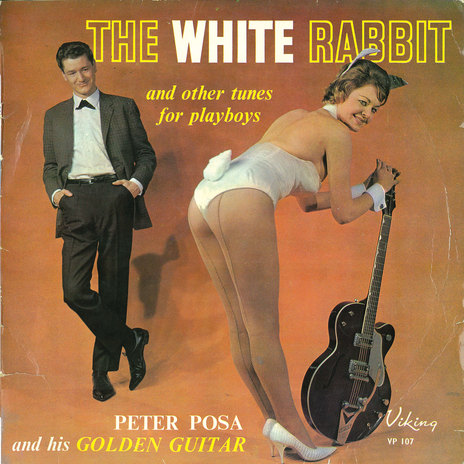

It was Dalton who provided Dinah Lee with hip overseas material such as ‘Don’t You Know Yockomo’, ‘Reet Petite’ and ‘Do The Blue Beat’. Although he had a technical rather than musical background, he had good instincts for a song and contracting the right musicians. For a period Viking also owned Mascot recording studio in Auckland, run by engineer Bruce Barton. With successes such as Peter Posa's ‘The White Rabbit’ in 1963 and ‘Blue Beat’ the following year, then releases by Lou and Simon and Garner Wayne, the company was not so reliant on its distribution of overseas labels, and Riley also expanded the number of Polynesian releases, which sold well in the islands.

Riley became more interested in book and music publishing, especially on Māori topics.

Late in the 1960s, Dalton left the company to manage artists, so Viking lost its A&R man. Riley became more interested in book and music publishing, especially on Māori topics. Seven Seas is still the name of Viking’s publishing wing and, in the years the label was active with new releases, it is extraordinary to consider how boldly Riley explored new territory. The company opened offices in Australia and Britain, distributed discs that included Latin-American artists, Chess R&B and even, for a brief period when they held the Elektra account, The Doors.

After leaving Broadcasting in his late 20s, Riley learnt the record business from the ground up. In Viking’s earliest days he worked at the Lamphouse record counter to pay the bills (and find out what the public wanted). He took his first releases home in batches on the bus to pack at night. To promote ‘The White Rabbit’, he sent carrots to radio DJs as a promotional gimmick. Viking pushed the boundaries of respectability in the 1960s with many releases by cabaret drag act Noel McKay, including six EPs in the Party Songs for Adults Series, plus an EP of “songs for sophisticates” called You Can Call Me Tanya (Wellington singer Marise McDonald as “Tanya”, with the Garth Young Trio). In the 1990s, Riley researched, wrote and published the definitive book on traditional Maori medicine. Murdoch Riley certainly ran the archetypal New Zealand indie that had a go at everything, and with a DIY approach.

--

Murdoch Riley died on 31 July 2022, aged 95.