Phil Judd

aka Mr Phudd, Judsy

Troubled genius, avant-pop savant, call him what you will, Phil Judd is one of the most significant talents to have emerged from the claustrophobia of mid-70s NZ, and his career path the most bewildering.

Think about it: from Split Enz to the Suburban Reptiles to The Swingers to solo soundtrack work to Schnell Fenster to Mr Phudd. It's quite a stretch, but everything Judd has turned his attention to has contained his tense, acerbic humour and singular take on pop music.

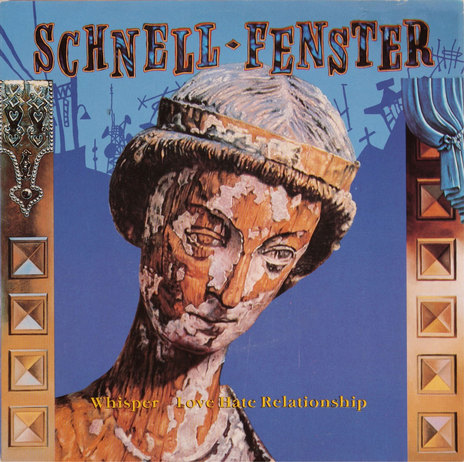

Schnell Fenster's 1988 single, Whisper

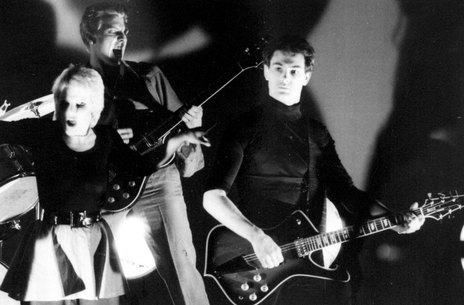

The Swingers at TV2 Studio, Auckland, November 1979

Photo credit:

Photo by Peter Tocher

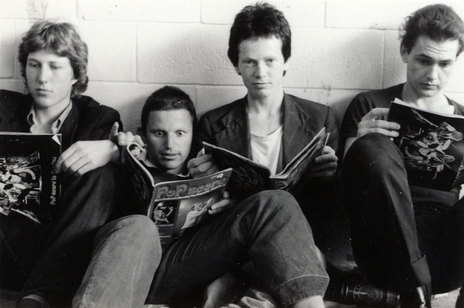

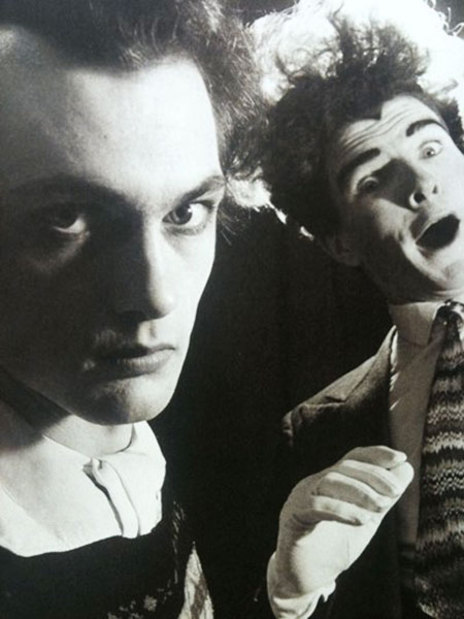

The Enemy with Phil Judd - Alec Bathgate, Chris Knox, Mike Dooley, Phil Judd

Photo credit:

Photo by Murray Cammick

Phil Judd - Rendezvous

Phil Judd - No-One’s Best Man

Phil Judd, 1976

Suburban Reptiles - Saturday Night Stay At Home

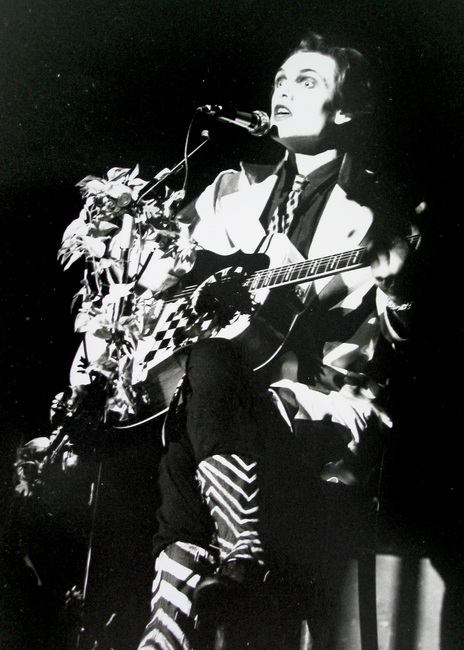

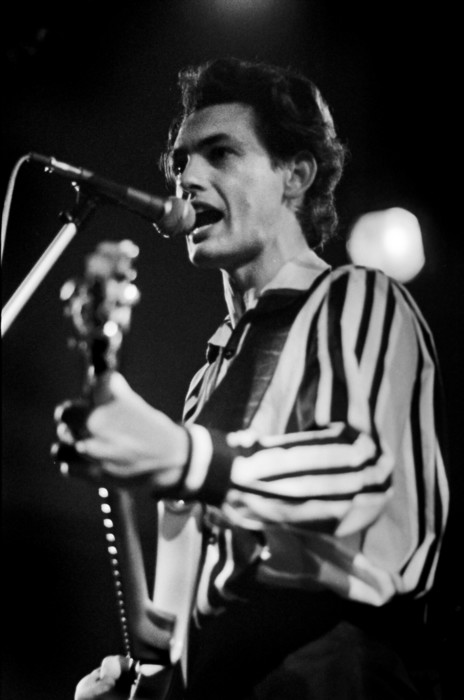

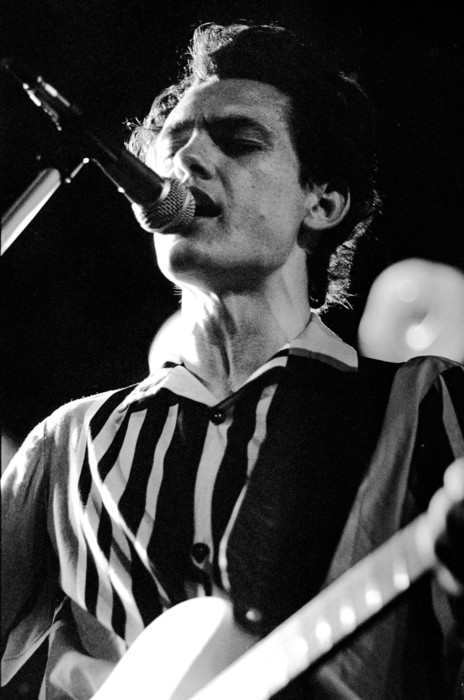

Phil Judd with The Swingers at The Windsor Castle, Parnell, Auckland, late 1979.

Photo credit:

Peter Tocher

Phil Judd with The Suburban Reptiles on the Saturday Night Stay At Home video shoot. L to r: Zero, Buster Stiggs, Phil Judd

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg Collection

Schnell Fenster - Heroes Let You Down

The Swingers in 1981 - Phil Judd, Bones Hillman, Buster Stiggs

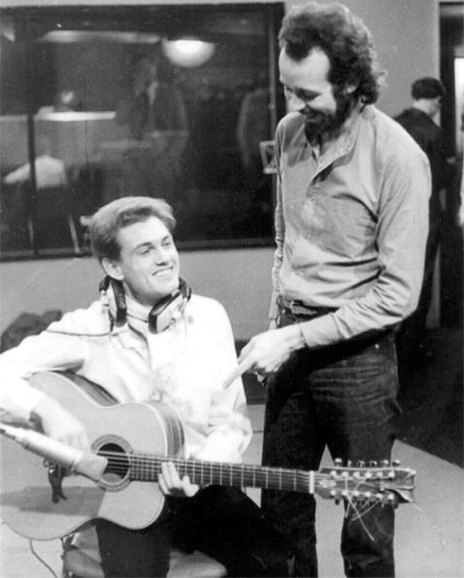

Phil Judd and Roxy Music's Phil Manzanera, London 1976 while recording Split Enz's Second Thoughts album

Phil Judd and Tim Finn, 1975

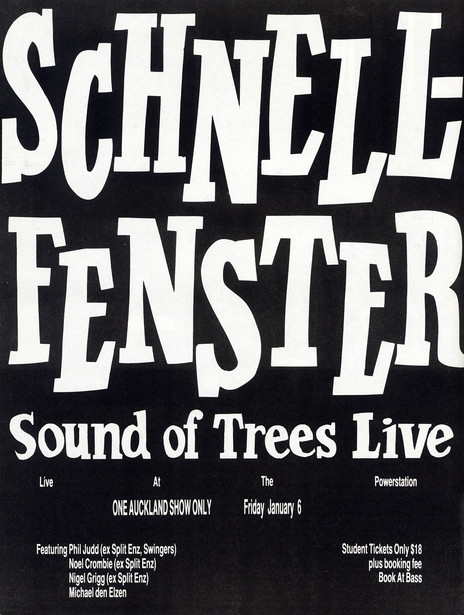

Schnell Fenster concert advertisement, Powerstation Auckland, Jan 6 1989. From Book of BiFim, 1988.

Phil Judd with The Swingers at Mainstreet, Auckland, late 1979.

Photo credit:

Peter Tocher

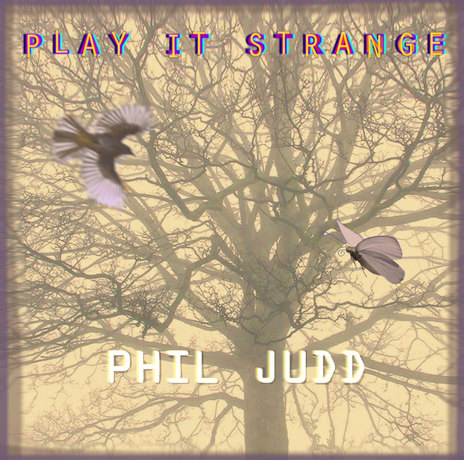

Phil Judd's 2014 album Play It Strange, built around a song of the same title, written and performed - but never recorded - by Phil Judd with Split Enz in the mid 1970s

The Swingers - It Ain't What You Dance It's The Way That You Dance It

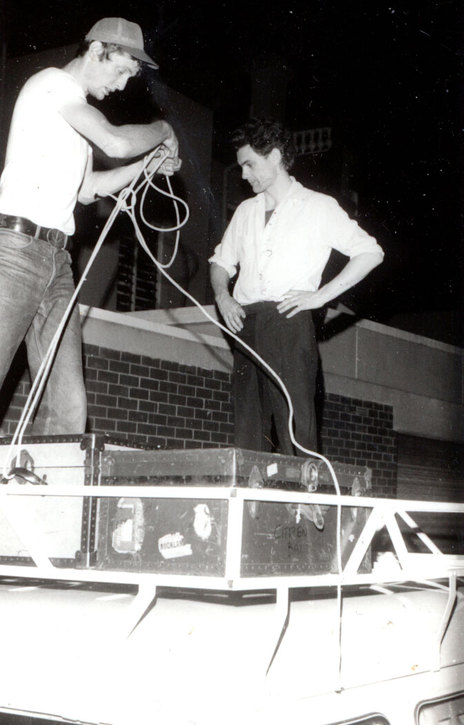

Phil Judd with Glenn Nacey at left, loading out of The Windsor Castle in Parnell, Auckland, after a Swingers gig in the early 1980s

Photo credit:

Photo by Murray Cammick

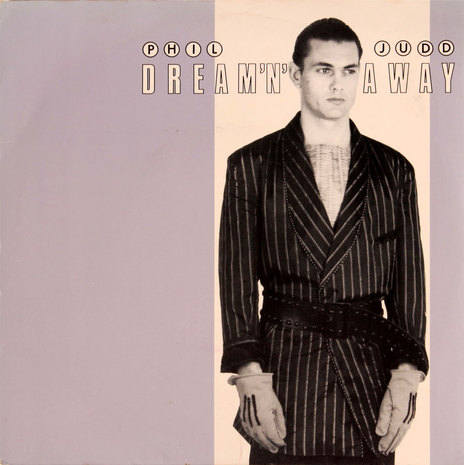

The Dream Away solo single, 1983

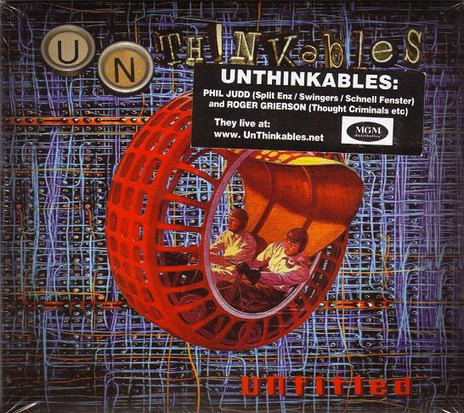

Untitled, the 2008 album by The UnTh!nkables, a duo of Phil Judd, and Roger Grierson (a New Zealander, formerly of Australian band The Thought Criminals).

Phil Judd & Tim Finn - Long Hard Road

Schnell Fenster - OK Alright A Huh Oh Yeah

The Swingers - One Track Mind

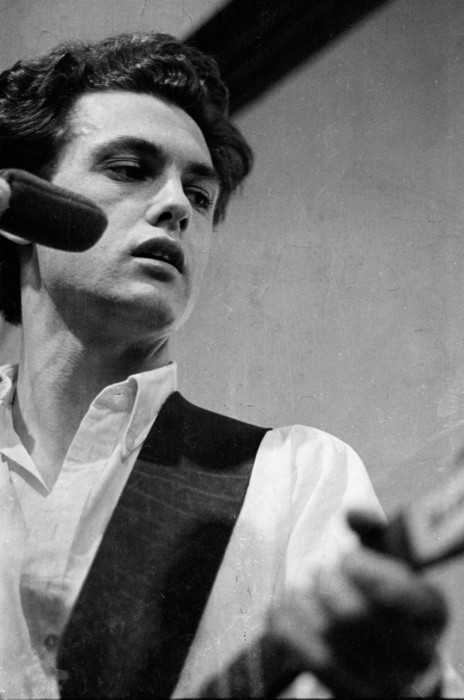

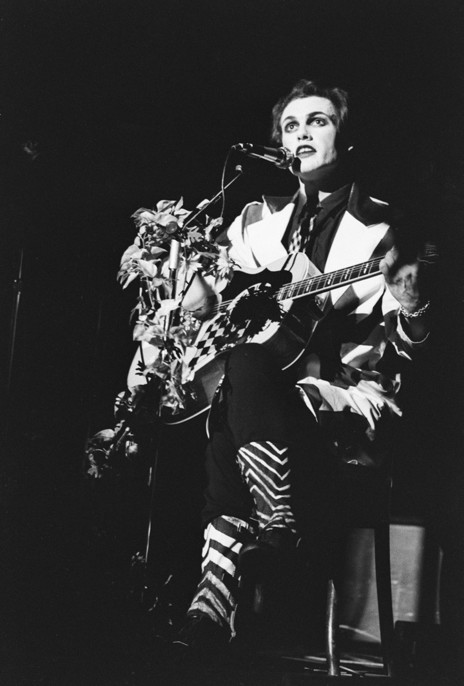

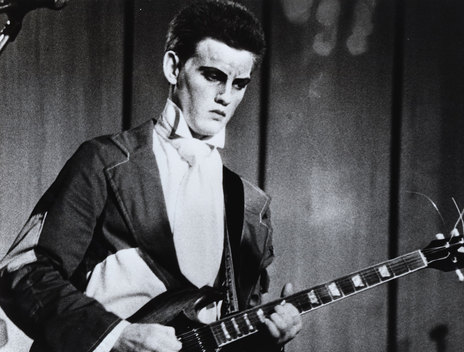

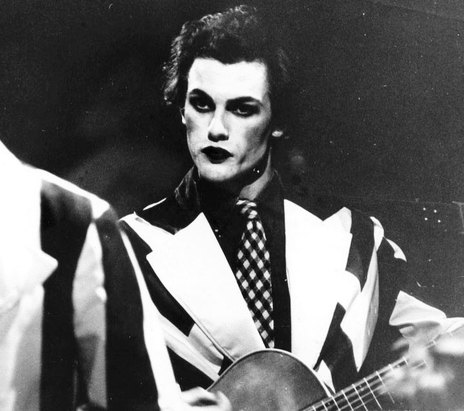

Phil Judd, Split Enz, Auckland Town Hall, 1975

Photo credit:

Bruce Jarvis Collection- Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1704-1043B-34

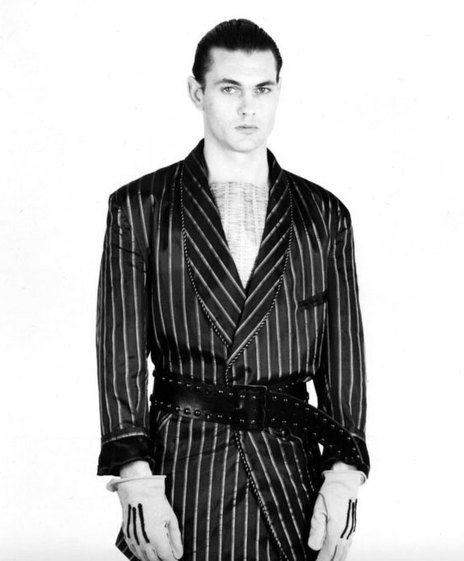

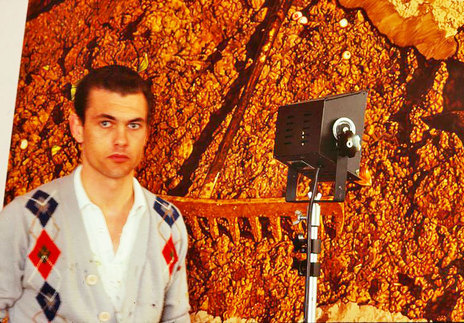

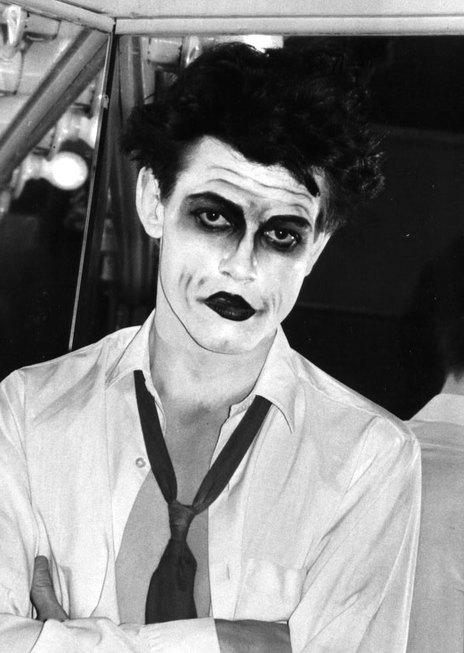

Phil Judd in a 1983 Mushroom publicity shot

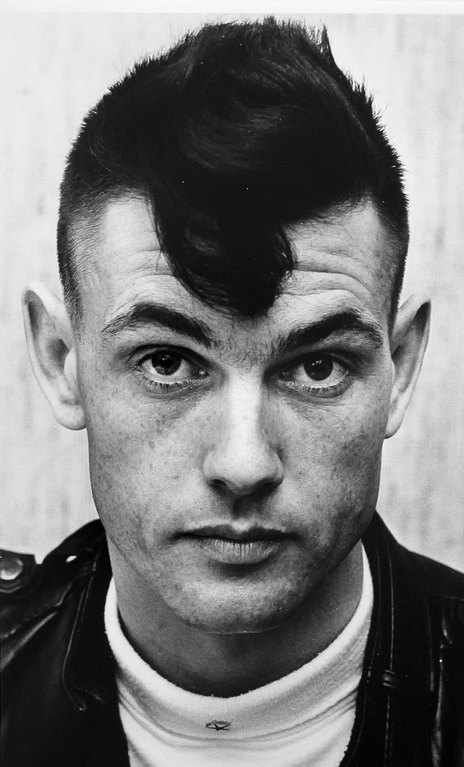

Phil Judd 1976

Photo credit:

Murray Cammick Collection

Phil Judd in a still from Starstruck

The Swingers at TV2 Studio, Auckland, November 1979.

Photo credit:

Peter Tocher

Phil Judd in his flat in 1985 just before heading to London to play on Tim Finn's Big Canoe album

The 1990 Phil Judd and Tim Finn single The Hard Road, taken from the soundtrack of the 1990 movie The Big Steal. To date it's the only single released by the founding members of Split Enz as a duo.

Split Enz- Spellbound (The Grunt Machine)

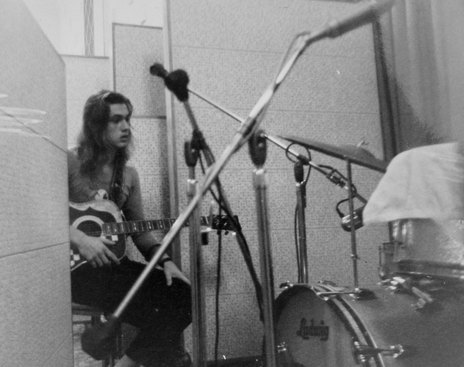

Phil Judd recording in Auckland with For You with Split Ends, February 1973 at Stebbings Studios, Auckland

Phil Judd - Dream'n' Away

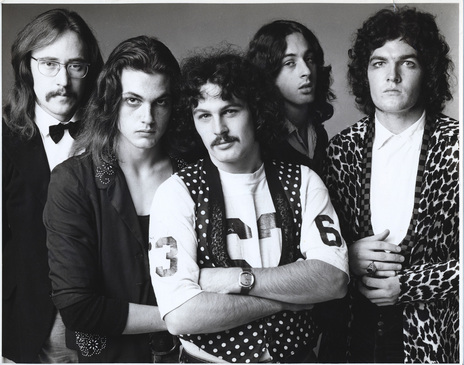

Split Ends 1973 L to R: Wally Wilkinson, Phil Judd, Mike Chunn, Geoff Chunn, Brian "Tim" Finn

The Swingers - More

The Swingers at Mainstreet, Auckland, late 1979.

Photo credit:

Photo by Peter Tocher.

Phil Judd in 1976 onstage with Split Enz in Auckland

Phil Judd backstage 1976

The Swingers - Counting The Beat

Phil Judd, circa 1982

Phil Judd with The Swingers at Mainstreet, Auckland, late 1979.

Photo credit:

Peter Tocher

The Swingers - One Good Reason

Split Ends at Ngaruawahia, January 1973 - Mike Howard, Phil Judd, Brian Tim Finn, Jonathan Michael Chunn

Photo credit:

Photo by Larry Jordan

Schnell Fenster - Love-Hate Relationship

Trivia:

Judd is also an accomplished visual artist, and has incorporated his flair with a brush and paint into his album artwork. His brilliant cover for the classic Enz album Mental Notes is a case in point, although his distinctive visual style can be found dotted throughout his career, even up to the arresting artwork for his last two solo albums. He has exhibited sporadically, and several galleries own his work.