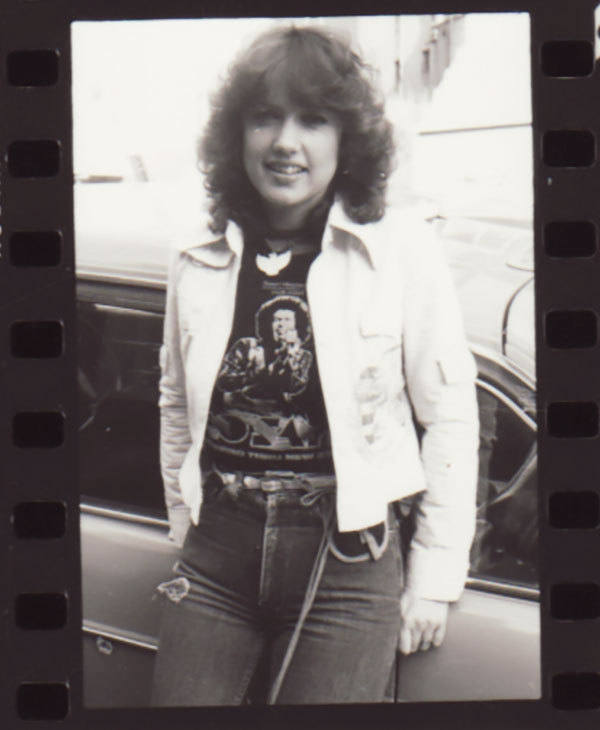

An early 1980s Australian publicity shot

This is an extended transcript of a phone interview recorded on September 12, 2001, a day after 9/11. Sharon O’Neill was in her Christchurch hotel, touring as a guest on the When The Cat’s Away Tour. I was calling from Auckland with a deadline to meet for the October, 2001 issue of RipItUp, but the ominous events in New York just 24 hours ago hung over the conversation. Sharon was as low-key and friendly as she was 20 years earlier, when the young singer-songwriter was the new kid on the block at CBS Records.

When did you start writing?

“I started writing songs myself, putting poetry to music, on guitar and piano when I was still at college. I had a folk group in my hometown, Nelson, when I was 15 or 16, doing folk clubs on Sunday and cabaret spots.”

“Moving to Christchurch was the first big deal because I lived at home in Nelson until I was almost 20. The gig came up in Christchurch with Chapta. For me it was a big deal because I left home, went flatting and was launched into a full on rock and roll band and the lifestyle that went with it.”

- Photo by Murray Cammick

How long were you in Chapta?

“Not very long. It was probably only three or four months. It was a trial for them, they were trying to rejuvenate the band and they decided that getting a female singer would boost that. They had been together for a long time and their lead singer left and it disintegrated which was a bit of a shock. Everybody wanted to go their separate ways.”

”I hung around in Christchurch for a bit. I dabbled with things solo wise. I made a couple of TV appearances. I drifted back into being in a band again. The solo thing didn’t click with me at that point.”

“After Christchurch I went back to Nelson. Then I went to Wellington. I even joined The Rumour for a while. Two guys that went way, way back. They decided to add a female too, I think I was the token ‘let’s get a female in the band’ person. That took me to Auckland briefly.”

Was Wellington your home base?

“My home base was just the road. Before I got to Wellington and planted any roots, I did the NZ breweries circuit. I remember doing residencies in Hastings for three months or Gisborne for six months. You either flatted or lived in the staff quarters and you played three or four nights a week and a matinee on Saturdays. That was your bed and butter – touring around the North Island with bands Libra and Jessica with guitarist Brent Thomas who became my husband, now my ex husband. We went back to Wellington and joined a band called Shiner. We spent six months in Asia. It was after the Shiner experience that I explored more of my own songs, went solo and got some demos done.”

- Photo by Murray Cammick

There was talk of you signing to EMI and in 1977 producer/manager Alan Galbraith had you touring with Mark Williams.

“Alan was babysitting me for a while.”

Where did you record your songs?

“At NZBC Broadcasting House [Wellington], a friend of mine, Dick Le Fort recorded a few songs for a 2ZM radio show Homegrown. A memory I will always hold dearly is doing vocals with the tea lady coming through the control room. That meant we had songs on tape. Dick Le Fort shopped my original songs around to some record companies and we got interest from CBS in Auckland.”

In 1978 John McCready, the former Philips Records executive who had signed the young Shona Laing earlier that decade, opened the first CBS Records office in NZ and started actively signing NZ artists.

How important was John McCready for you?

“It was very important. I knew for a fact that John was only interested in signing me because I had original material. That to me was fantastic. It was a bit scary when somebody of John’s status said, ‘I really believe these songs are going to work and we are going to market these and they are going to happen for you.’ He was a very important person at that point in my life. He was very encouraging. We had a volatile relationship. Things sparked. I learnt a lot from John. All the cards were on the table.”

Were you self-managed?

“I was really, it all fell into place. We did the albums [This Heart This Song 1979, Sharon O’ Neill 1980] and everybody in the company structure looked after me. I didn’t really seek management until I had to go to Australia.”

Your second, self-titled album was changed for Australia.

“They retitled it Words in Australia with an added song John really wanted me to do, which was the first cover I had ever done, ‘How Do You Talk to Boys’ produced by expat Kiwi Peter Dawkins [Dragon, Mi-Sex].”

“I didn’t want to start my career in Australia with somebody else’s song but John felt strongly about it. He sent me the cassette of the demo and said this will be your first Aussie No.1. and I went, ‘Am I going to be too precious about my own songs and really stupid here or am I going to give it a go?’ It worked but wasn’t a hit. Maybe it made the Top 30. But it also empowered me a little with my own material and I stuck to that and got a lot more confidence.”

- Photo by Murray Cammick

What was your biggest hit in Australia?

“ ‘Maxine’ on Foreign Affairs. ‘Words’ broke the ground. It wasn’t a huge hit but it was a hit in Queensland and cities like Newcastle and Melbourne.”

Was Foreign Affairs the most enjoyable recording sessions?

“No, but it was a highlight for me because it was done on the West Coast of the USA with a very important person in my life at the time, John Boylan [who produced Linda Ronstadt in the 1970s], who was so enthusiastic over my songs and pulled it all together and pulled in so many friends. I was such a fan of these people who came and played on the album that I was shaking in my shoes when they came into the studio. For me it was like visiting Hollywood. Wonderful players but no more wonderful than anybody else who has played on any other album.

Who were some of those heroes who played on the album?

“One day we were missing a harmony on one track and John Boylan the producer said, ‘Hang on cutie,’ as he used to call me, and he left the room and came back with Don Henley."

– Sharon O'Neill

“Tom Scott on sax on ‘Maxine’ and drummer Arnold McCuller and guitarist David Lindley who had I had only seen on stage and heard play with Jackson Browne, they did the vocals on ‘Maxine’.”

“One day we were missing a harmony on one track and John Boylan the producer said, ‘Hang on cutie,’ as he used to call me, and he left the room and came back with Don Henley. He just happened to be in the building and came in a sang the harmony and left and that was that. Totally gratis. That was unbelievable as I was such a fan of the Eagles, Karla Bonoff, David Lindley, Timothy B. Schmidt, Bill Payne. I could go on, wonderful people.”

Did you feel in control of your career once you went to Australia?

“I had a lot of control but not as much as I had in New Zealand. It wasn’t a family. It was a much bigger corporate situation and there were a lot more bands under the same umbrella that were very successful. There was a lot going on. For me, my mouth hung open and I went, ‘My god this is serious shit going on here.’ Being a songwriter myself I had that much control and control with producers. I have always been strong in that area. I don’t think you can not be if you are a songwriter, otherwise forget about it. Why are you there? The structure, the corporateness of it and the marketing, for me it was humongous and I am sure if you go to Europe or America it just gets bigger and bigger. But I stayed in control best I could.”

“I did like playing keyboards live on stage. They wanted me out from behind those keyboards to the front of the stage by hook or by crook. I did it gingerly, a song at a time. I actually really enjoy it out there as a communicator, as a songwriter to not have to worry about the keyboards but on the other hand if I am singing something very special there is nothing like the feeling of sitting down at a piano on stage in an auditorium and playing a ballad that you have written and have that communication and silence with the audience. Maybe it wasn’t such a bad thing to get me out from behind my little apron with the black and white notes on it.”

Did they have a concept of how you should be marketed in terms of image and videos?

“I fought that a little bit but I went for the rock chick thing as I was feeling it at the time, so nobody told me what to wear. I just went with the flow 1975 to 1985. I hate to say ‘the 70s’, I hate to say ‘the 80s’ but I straddled those decades and I think they’re both pretty cool right now. I wore what I wanted but in Australia every record label had a “certain person” who had a Top 10 record who looked like that and sounded like that and every other company desperately wanted one. They would look at me and I would go, ‘Nuh, it’s not me, I’m not goin’ there!’ I was trying to establish myself as a singer-songwriter. It was hard work, it took a little longer that way. It’s easy to take the plunge off the side and do that whole marketing thing but no, yuck, that’s gross.”

- Photo by Murray Cammick

Did the success of Foreign Affairs (1983) create a strong live career for you?

“Not really, because when it was working I had all the crappola go on with the record company that we really don’t even need to go into because it’s history now. It was a giant hiccup. The album was working really well and we could have gone on and done another one and everything could have been hunky dory but the crap hit the fan and it wasn’t to be and that was a real shame.”

You were having success, what would go wrong?

“Basically it was to do with the renewal of the contract and mutual unhappiness on both sides in terms of pulling the next project together and the ripple effect was just ridiculous. It could have been easily talked out over a cup of coffee but it wasn’t and it lingered on and on and there were a lot of changes going on in the record company, as happens and it has happened so many times to me but not so devastatingly. These changes happen and they really affect artists and people don’t realise that, it’s all behind the scenes, they really affect projects and people’s attitudes and energies. That is actually what happened and it really got into a dark hole. I would wake up in the morning and go what the ‘four little asterisks’ is going on here?”

Were you stopped from recording?

“Legally I couldn’t go into the studio. I couldn’t do anything except write my songs. I could have performed live but it’s too expensive to do that if you’re not promoting anything except bad vibes. It is going to cost you eventually.”

Was it a problem in part caused by your management?

“I think the problem was with the record company. With my knowledge now, in hindsight the way the contract was interpreted and the particular word that was really my demise has been taken out of contracts since. It doesn’t exist because it’s so interpretable.

Which word was that?

“I can’t say but they used it with glitter on it and it sucks. You sign these things without consultation with a lawyer, which nobody really does these days. My contract was signed in 1978. They pull it out of the hat, because they can and they’re corporate and they have the money to do it. It just got really ridiculously petty.”

You don’t think in hindsight you may have been too stubborn or too demanding yourself?

“Not demanding and stubborn, I think, maybe if I had known what the outcome would be or where it could have gone I probably wouldn’t have and [there are] some days when people ask me that I go, ‘I would have bloody well done it again.’ It depends on what frame of mind I am in.”

“I do know management came to me and said, ‘This is completely up to you, here’s the way it looks, you can either do this or leave it alone.’ I said, ‘No I wanna do it.’ Maybe that was because of my genes, it could be a hormonal thing, it was just the way I felt. It was a bit like a Southpark thing, ‘Screw you I’m going home.’ It was like, ‘Screw you I’m going for this.’ I just had to pursue it. There was this morbid curiosity, I had to know why all this was happening.”

Did it put your career in hiatus for four years?

“Even longer, it’s a bit of a blur. I was really angry. I put my mind to other things, writing and travelling. It was kind of an upheaval. I met my partner of 17 years. There was all that stuff going on too. When the shit hits the fan, Murphy has a party.”

When you went to Polydor in 1987 was it easy to rebuild you career?

“No it wasn’t easy. I was very fortunate I got that deal. A friend, Roger Davies, who was managing Tina Turner, secured the Polydor deal out of the UK for me. Unfortunately being done out of the UK probably was a mistake as when it gets back to Australia, to the home company it’s like – ‘It was done in the UK. We weren’t really involved’ – so there wasn’t really a great family feeling with the record company. I did all my tour and there wasn’t really any on hand support.”

“Margaret Urlich and I have talked a bit about this on the tour, it’s this corporate thing with these big companies, that it’s sometimes better off with your homegrown people who really have hands on enthusiasm and who are not caught up in all the bullshit. It was great doing the two Polydor albums, I put a lot of hard work into them but the last album Edge Of Winter is as scarce as hen’s teeth, I’ve only got one copy. They only made a certain amount.”

- Photo by Murray Cammick

Did Dave Dobbyn do an Australian tour in your band?

“I hadn’t moved to Australia at that point. We went over and did the Boz Scaggs support and our own gigs. It was wonderful. He played guitar and sang amazing vocal harmonies.”

How did you get involved in the Smash Palace soundtrack (1981)?

“I was approached by director Roger Donaldson. I went to Nelson, to Mum and Dad’s house to write. It took about a week and then took it up to Auckland. I loved doing it.”

Did your dispute with CBS affect your song publishing?

“When I signed to CBS Records I was cajoled into going with their publisher. They were connected at the time. [CBS sold their publishing company in 1986.] But when the crap happened it wasn’t really an issue.”

“My advice would be if you believe in your songs that you hold on to that publishing until the very last minute when you can swing a good deal. You can do an album and keep your publishing to yourself and if that album works then you can shop around. If you have a hit, the power lies with you and you can get a good deal. I signed my publishing the day I signed with CBS Records, it was part and parcel. That was the old days, things have changed and a lot has been learned.”

What has the 90s involved for you?

“Musically, stepping out of the loop of putting out albums and touring and getting back to songwriting which was Plan A in the first place. Writing for myself and writing with my partner Alan Mansfield, we did a lot of work for Dragon. He has worked over many years with Robert Palmer. We wrote his last single.”

“We’ve just signed with a publishing company called Peer Music in Australia who are based in Nashville and Los Angeles. They are very hands on, they go for covers big time on TV shows etc. That’s our cup of tea. They are a lovely little company in Sydney. They keep in touch and let us know who is looking for material. It helps to know these sort of things.”

When you spoke with Margaret Urlich about the difficulties in being with a big record label were you referring to staff changes, the people who signed you leaving?

“We did not discuss specifics. In the corporate situation you feel like a blur yourself and you sometimes wonder if you’re not a blur to them. It’s such a big structure and so much goes on behind the scenes.”

“I’ve talked about this with Annie [Crummer] too. She had to fight against it too. At least her record company came and asked her, ‘Can we put out a best of?’ But when they own your songs, you go to a store and you’re looking in the real cheap bins out the front of a record store and you find a CD with an old photo, a new title and old tracks on it. They have that control over you and sometimes it’s a real bitch. It is very unartistic. It’s all because of that corporate thing. Who knows if the guy at the top knows if it’s out there, but it goes on and they recoup their money that way. It’s fine and dandy when you’ve got a record in the Top 20, you’re the bee’s knees, you’re the taste of the month. But when you’re trying to maintain a career and you have a hiccup of an album, maybe the next one is going to be the big one. If you don’t have consistency behind you, it is very difficult.”

Has anyone from Sony asked you to do a best of with your co-operation and input?

“No they never have, I just find them in the record stores. There has never been anything like that in New Zealand and I’d love for something classy out in New Zealand. It’s so nice to be on the When The Cat’s Away tour and do these old songs and hear that people remember them and love them. As you can do so much these days digitally to remaster, it would be great to put a really classy “best of” collection out.”

Sharon O’Neill’s 2001 wish came true and she selected the 20 tracks for her hits package, Words: The Very Best Of, which entered the NZ Album Sales Charts at No.7 on the April 28, 2014 chart.