Daniel Beban’s 2024 book Future Jaw-Clap depicts the improvisatory music scene that emerged in Wellington in the late 1970s and early 80s, which gave birth to experimental bands such as the Primitive Art Group, Six Volts, and the Braille record label. The book evocatively mixes social and musical history and shows the impact one can have on the other. In this excerpt, he describes a city in which the cloud of Muldoonism inadvertently fostered anarchistic creativity, including the fledgling Primitive Art Group.

Primitive Art Group was a pioneering band of self-taught musicians from Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, Aotearoa, who tenaciously pursued their own notions of improvisation, free jazz and collectively structured music. The band seemingly emerged out of nowhere. They had practically no local role models and very few contemporaries.

Primitive Art Group, outside Stuart Porter's flat, Vivian Street, Wellington. From left: Anthony Donaldson, Stuart Porter, David Watson, David Donaldson, Neill Duncan. Absent: Pamela Gray. - Neill Duncan Collection

The first seeds of what would become Primitive Art Group were planted by saxophonist Stuart Porter and drummer Anthony Donaldson in 1978. The duo expanded through several permutations before settling into a five-piece in 1981, then growing into the wider Braille Collective in 1984, spawning more than a dozen ensembles and releasing LPs on their own label.

Braille Collective c.1986. From left: Anthony Donaldson, Gerard Crewdson, David Watson, Janet Roddick, David Long, David Donaldson, Stuart Porter, Richard Sedger and Neill Duncan. - Marcel Tromp

In 1986 the members of Primitive Art Group and Braille split in a number of different musical directions, spreading the branches of this family tree further out into time and outside its roots in Wellington. My 2024 book Future Jaw-Clap: The Primitive Art Group and Braille Collective Story traces the story of these musicians in the city, from 1978 until the early 1990s.

Primitive Art Group created sounds that resonated deeply in a local setting, but which have slipped into the background noise in the world’s cluttered sonic space. Relatively little is known about Wellington’s tradition of free jazz and improvised music outside the city.

Primitive Art Group 1981-1986 album cover, released in 2024.

This is partly due to the realities of practising an alternative art form within a conservative cultural mainstream. In Wellington this music has always been a fringe activity played by stubbornly independent people operating outside established institutions. And while Braille embraced self-publishing – indeed at their peak the Collective managed the most active artist-run record label in the country – for this community the recorded medium has always been of secondary importance to live performance. The Collective’s publicly released records, for all their worth as works of art and historical markers, don’t reliably portray the music that was made. Nor do they do justice to the scale of work going on within and around this scene.

Wellington, the place, is central to understanding the story of Primitive Art Group and Braille. The city, much of it built on steep hillsides and almost surrounded by the sea, is dominated by its geography and weather.

Windy city struggle

By the time the Primitive Art Group story begins in the late 1970s, Wellington was a small, grey, windswept city of around 160,000 people. Hidden behind its dull exterior was an active community of creative artists and colourful eccentrics tucked away in the city’s back streets, such as Carmen, the city’s transgender queen, who for a decade ran the Balcony, an exotic speakeasy that alternated risqué stage shows with avant-garde theatre productions. But Carmen’s Balcony was on the way out, closing in 1979. The two big breweries, Dominion and Lion, controlled virtually all the pubs and with them the live entertainment scene. This was good for covers bands and dependable crowd pleasers, but for bands that didn’t fit into the pub mould, gig options were severely limited.

The few independent venues that popped up during this time, like the Mindshaft, Billy the Club, or The Last Resort down on Courtenay Place near the vegetable markets, found it impossible to get an alcohol licence. While the energy of these spaces flared brightly, in this environment survival was difficult and many folded before their second birthdays. For audiences whose tastes veered away from the mainstream, entertainment options were lean.

“The cold hard reality was that it was quite a boring place back then,” says Gary Steel, central driver of Wellington’s underground music press through the early 80s. “It was a creativity born of frustration at lack, and I guess a lot of good scenes arise out of that kind of scenario.”

1986 Braille collective tour in association with NZ Students Arts Council. Concerts at Streets Ahead Performance Cafe in Wellington included Jungle Suite, Motto, The Family Mallet, Four Volts and Black Sheep. Primitive Art Group concerts held at Limbs Dance Studio and Shadows in Auckland. - New Zealand Student Arts Council poster (NZSA90318)

Like the physical setting, the historical moment was unique and is crucial to fully grasp Primitive Art Group’s music. The group’s story traces the contours of a particularly turbulent time in New Zealand history, beginning in a social climate defined by the last vestiges of the post-Second World War welfare state and ending up in the wastes of early neo-liberalism. Following oil crashes and economic recession, and punctuated by protests over Māori land rights, the Vietnam War and nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific, New Zealand’s veil of united optimism of the early 1970s had disappeared by the end of the decade. The South African rugby tour of 1981 laid open these bitter divisions, with the staccato cracks of police batons hitting the heads of anti-apartheid protesters echoing loudly around the city. Visiting nuclear-powered US warships similarly provoked loud reactions.

A licence to challenge

Like others, Wellington’s improvising musicians could not help but be affected by these events. Their music was charged with the atmosphere of the times, while they contributed their own noise to the waves of sound that ebbed and flowed around the city.

At the same time, punk energised a generation with a licence to challenge accepted norms. Serendipitously, the punks, artists and activists of the time had the perfect character to rally against: authoritarian, anti-liberal, old-fashioned and sexist, Prime Minister Robert Muldoon was the era’s bogeyman, contributing an unseen presence to much of its music and art.

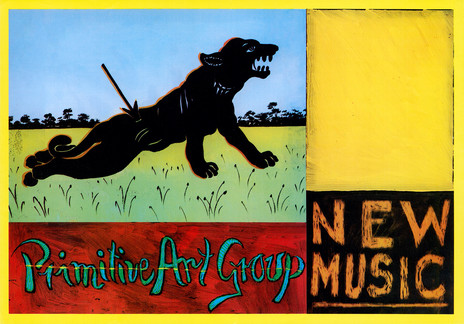

Primitive Art Group poster c.1986. - New Zealand Student Art Council Posters (NZSA90419)

Although widely despised, Muldoon was a very necessary element in this fertile time of politics and art, conveniently forcing together anyone opposed to the conservative mainstream he embodied. Indeed, this alienating character was a wellspring of inspiration for the many artists fervently attacking the era’s bad politics. Curiously, in a seemingly contradictory act, the Muldoon government’s employment schemes offered regular income to many artists, allowing them to pursue their creative work full-time. Out of these elements came a flowering of arts activity of which Primitive Art Group was a small but vital element.

Wellington city itself went through dramatic physical changes through this time. As old industries pulled out of the city in the 1970s they left an abundance of old warehouses. For a brief time these were eagerly inhabited by artists and contributed to a lively creative community before the wrecking balls of the 1980s economic boom laid waste to many old buildings.

This was a fruitful period for music. It was a time of flux and change. Old structures and systems were being challenged. People were searching for new ways and new modes of expression. The intersection between the external forces imposed on the music and the musicians’ own creative impulses is one of the underlying themes of the book.

How Primitive Art Group navigated this shifting ground highlights the uncertain role that music has in our society, as a creative outlet, a cultural barometer, as entertainment, and as a commodity. The musicians’ story through these years is a complex and interwoven dance of creativity, politics, economics, collective stories and individual struggles.

Do your own fuckin’ thing

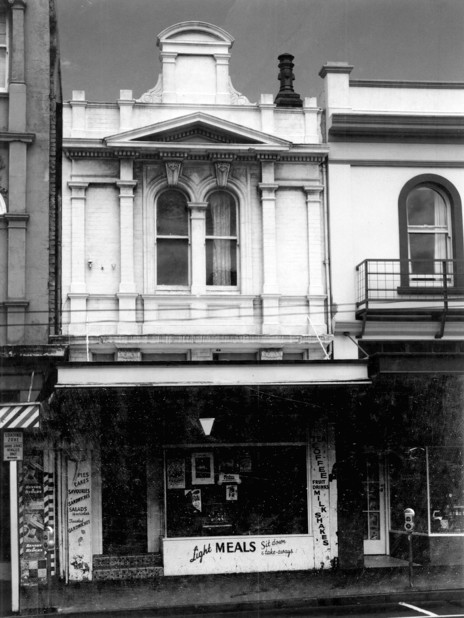

March, 1978: Situated right in the heart of Cuba Street, just south of the Ghuznee Street corner, the Coffee Pot was a small, no-nonsense workers’ eatery serving light meals, pies, cakes and filtered coffee. Since the relaxing of liquor laws in the late 1960s, the city’s classy European café culture of the post-war years had retreated to a tried-and-true formula of fried food and stale pots of weak, drip-fed Cona. The Coffee Pot adhered strictly to these trusted principles.

The Coffee Pot, Cuba Street Wellington

If Wellington’s improvised music scene has a creation myth, the setting is the unassuming Coffee Pot, sometime around March 1978. It was here, among overalled fish-market workers and moustachioed office managers, that Stuart Porter and Anthony Donaldson met for the first time. Their restrained discussion added a barely noticeable layer to the drone of lunchtime conversation. But it laid the groundwork for their collective musical endeavours over the next decade and paved the way for a tradition of creative music making which is still alive in the city more than for 40 years later.

Sitting down with their mugs of brewed coffee, the budding improvisers sniffed around each other like two young dogs, name-dropping their favourite albums and trying not to let their excitement show as they agreed on the importance of Paul Bley, Steve Lacy and Ornette Coleman among others. Even though LPs from independent labels were almost impossible to buy at that time, they had both heard some of the English free improvisers on ECM’s release of The Music Improvisation Company featuring Derek Bailey and Evan Parker. Both had checked out Cecil Taylor’s music, which was available through his Blue Note releases. And without a doubt, they both agreed, Art Ensemble of Chicago’s Fanfare for the Warriors was a classic.

As the conversation turned to their own music the talk became more general, the two mulling over broader concepts and what they hoped to achieve together – that they would work together from now on was a given.

Improvisations - Anthony Donaldson and Stuart Porter

Improvisation was the obvious starting point and fundamental element. Both had already been trying to figure out an individual approach to their instruments. What about developing a new kind of music together? Stuart especially was interested in finding a new sound through composing and experimenting with form. Several weak coffees later they’d settled on three guiding principles, which read like a mini manifesto: get your own sound; play original music; always strive to play new music. As Anthony suggests, the founding principles can be summed up in one, slightly more direct, edict: Do your own fuckin’ thing.

These principles weren’t always strictly adhered to, and the definitions of certain words like original would be stretched in the coming years. But at its core, the musical language of Primitive Art Group, and by extension, much of Wellington’s free music since, was built upon these simple concepts. And despite the development of structured compositions and a kind of coded musical language that evolved with Primitive Art Group, the initial thrust and the continued essence of Anthony and Stuart’s music making was collective, free improvisation.

Taking music “out”

Free improvisation was a relatively untested mode in the New Zealand musical landscape of the 1970s. Jim Langabeer was one of the few jazz musicians who had been investigating free playing since the late 1960s, firstly in Christchurch and then in Auckland. A saxophone, clarinet and flute player, Langabeer’s music was influenced by players who were at the forefront of developments in jazz in the mid-1960s: John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Sonny Rollins, and Ornette Coleman. Langabeer had spent time at the Creative Music Studio in Woodstock, New York, playing with luminaries such as Roswell Rudd, Pauline Oliveros, and Gary Peacock. Langabeer was pioneering music that was unorthodox for New Zealand audiences at the time, while his legitimate musical abilities allowed him to work within conventional jazz as well as taking his music “out”.

Sound artist Phil Dadson, also based in Auckland, had worked with Cornelius Cardew in the UK in the late 1960s. On his return home in 1970 he injected some of Cardew’s ideas about non-standard musical organisation into New Zealand via the Scratch Orchestra and From Scratch. Conceptually driven, in the 1970s Dadson’s music explored aleatoric processes, working with and within nature, invented instruments and minimalist concepts. Dadson’s groups utilised improvisation in performances from the early 1970s, notably during the dawn-to-dusk Solar Plexus events, which took place in the parabolic cone of Auckland’s Maungawhau [Mt Eden] volcano.

Primitive Art Group, c.1983: David Donaldson, Neill Duncan, Stuart Porter, David Watson, Anthony Donaldson. - David Watson Collection

In comparison, Anthony and Stuart’s approach to improvisation was, at first, naive, even crude. Both had virtually no previous experience of music making, and neither had any direct connection to an international lineage. Instinctively they looked for guidance but a lack of local role models meant they were tuning into music via LP recordings of overseas players, far removed geographically and culturally, and often significantly delayed in time. Without first-hand experience of seeing improvising musicians at work, the influence that could be gained through recordings was limited.

“We really didn’t know much about the people we listened to, only what came through in their recordings,” says Stuart. “It wasn’t like you could really be influenced by that. You could be influenced by a person who you meet and work with and play with, but a record is just the same bunch of little notes over and over again.”

Non-virtuosic freedom

As musical newcomers they were grappling with their instruments and musical fundamentals at the same time as formulating a collaborative approach. Many of their role models – musicians such as Tony Oxley, Anthony Braxton and Cecil Taylor – had not only mastered conventional playing but had each developed a staggering array of extended techniques, allowing a seemingly effortless and limitless freedom of expression. Notoriously non-virtuosic, at least in a conventional sense, Stuart and Anthony were forced to find other means of bringing subtlety and artistry to their playing. Deftness of touch, a willingness to take risks, a dedication to close listening and a recognition of what not to play allowed them to forge ahead with their plans to create a new kind of music despite lacking some of the most basic technical skills.

Above all, both players possessed a vision of what they wanted to achieve and a strong conviction that this chosen musical path was theirs for the taking. “When I look back I just laugh, because I was so confident,” says Anthony. “I knew exactly what I wanted right from the word go. And the fact that I couldn’t play has never really been a consideration. I’ve always just tried to play how I’ve imagined it should sound, and when I was playing it always sounded pretty real.”

Their first forays into playing music together took place in Anthony’s tiny, rented cottage, one of several small cottages in the back garden of a Newtown house. Almost the entire floor space of his downstairs room, decorated like a relic of the 1950s, was taken up with his drum kit. Stuart recalls: “I’d squeeze in with my saxophone and we’d just blast away for hours and hours, jamming, improvising. We’d begun to call it improvising in those days. We must’ve picked up some fancy words for what we were doing. I’d go there, we’d start playing and three hours later we’d stop.”

In a recording that survives from their cottage jams, there are two distinct musical modes in operation. The first is a short excerpt of a drums and saxophone duet, fiery, loud and aggressive, their standard modus operandi at the time. The second, a trio with a viola player named Euan Frizzell, has an altogether different character. Here Stuart plays flute while Anthony plays bells, gongs, cymbals and woodblock. The music is uncluttered, filmic, surrounded by silences in a manner that hints at a Japanese influence, perhaps a nod towards the soundtracks of Kurosawa movies, favourites of the aspiring improvisers.

An important aspect of Anthony and Stuart’s early cottage sessions was the development of a commitment to listening as intrinsically fundamental to the act of making music. While playing, even in the more energetic pieces, each player would try to be as aware of the other’s sound as they were of their own. For this reason, Anthony’s drumming in particular tended towards a lightness of touch rather than the more powerful playing favoured by free jazz players from the US and the Continent. A light and often highly detailed approach to improvisation was practised particularly avidly by British drummer John Stevens in his group the Spontaneous Music Ensemble. Anthony had found a second-hand copy of the group’s LP Karyōbin and the sound on that record became a template for an approach to free playing.

Primitive Art Group on the cover of Wellington's TOM magazine, 1983

For Stuart and Anthony, improvising through close listening allowed them to enter a kind of ecstatic state, a feeling of being “in the moment”, the clichéd phrase commonly used to describe a sensation of being acutely present. It was a sensation the two musicians would aim for throughout their musical journey together. “You can feel it, the magic when the whole group is as one,” says Anthony. “Everything is absolutely happening. The whole thing’s just perfect. And it all centres around listening to each other. Someone does something and we respond to it. It’s that simple. As a player, if you’re in, you just know it. You feel you can do anything, and suddenly you realise that everyone’s in there, everyone knows, everyone’s supporting each other totally.”

At this stage their music making was confined to the four close walls of the Newtown cottage. Without an audience and with few other musicians in their orbit, Stuart and Anthony had almost no other ears to bounce their new ideas off. Listening sessions took on an increasingly ritualistic importance. “Anthony was serious, he was another Peter Baker,” remembers Stuart, referring to his friend, a Wellington sculptor. “He was very seriously into listening and playing music. Nothing much has changed. His idea of a good time was to go home to his cottage, have dinner, light up a joint and sit down with his record player and listen to something. Something that he’s been thinking about all day. He wants to listen to a particular record and a particular track, and he’ll listen to it. And then he’ll either get up and have a play or not.”

Primitive Art Group's 1985 album Future Jaw Clamp released on Braille Records.

The lack of an audience prompted Anthony to create imagined performance scenarios in his head. “What I started at that time and what I still do, every time I play the drums, wherever I’m playing, I pretend there’s an audience,” Anthony says. “When I sit down at that kit I’ve psyched myself into it, I’ve done some listening and now I’m ready. So I turn everything off, go over, sit down. I might have a few preconceived ideas, but normally I’m just sitting down like an open book. And when I start to play I pretend there’s an audience there. I pretend for instance that the gig’s starting with me opening. So I have to play well. I have to play inspired. It makes me play better. I’m more committed. If I make a fuck up I’ll definitely keep going, because I’m at a gig so I can’t stop, I’ve got to solve it without going over the same old stuff.

“And I pretend that there’s someone in the audience who’s important enough that I’ve actually got to play the best I’ve ever played. Let’s say, Duke Ellington’s in the audience. So maybe I should start pulling out my awesome tricks. But is that playing well? Okay I’ll get my shit round it. I’m gonna play artistically, something nice that doesn’t have to be complicated. So you start up, get your thing happening. Don’t fuck it up, this is nice. Just stick with this, just see where you can take it. Duke’s out there, he’s digging this for sure. It’s nice, it’s simple but it’s nice. Duke Ellington, whoever’s sitting there listening, I feel I can listen to it through their ears.”

An edited excerpt from Future Jaw-Clap: The Primitive Art Group and Braille Collective Story, by Daniel Beban (Te Herenga Waka University Press, Wellington, 2024)

--

Audio

The Primitive Art Group: a playlist by Dan Beban

RNZ: Future Jaw-Clap: the wild years of Wellington jazz, 6 November 2024

Read More

Witchdoctor Q&A with Anthony Donaldson and Stuart Porter, originally published in TOM magazine, 1983