In Touch

For six years from the early to mid 1980s, In Touch magazine and its several permutations did their best to prevent Wellington from devolving into a city dominated by ukulele slinging, Hawaiian-shirted Jimmy Buffett clones.

That’s my story, and I’m sticking to it. After all, I was its publisher and editor.

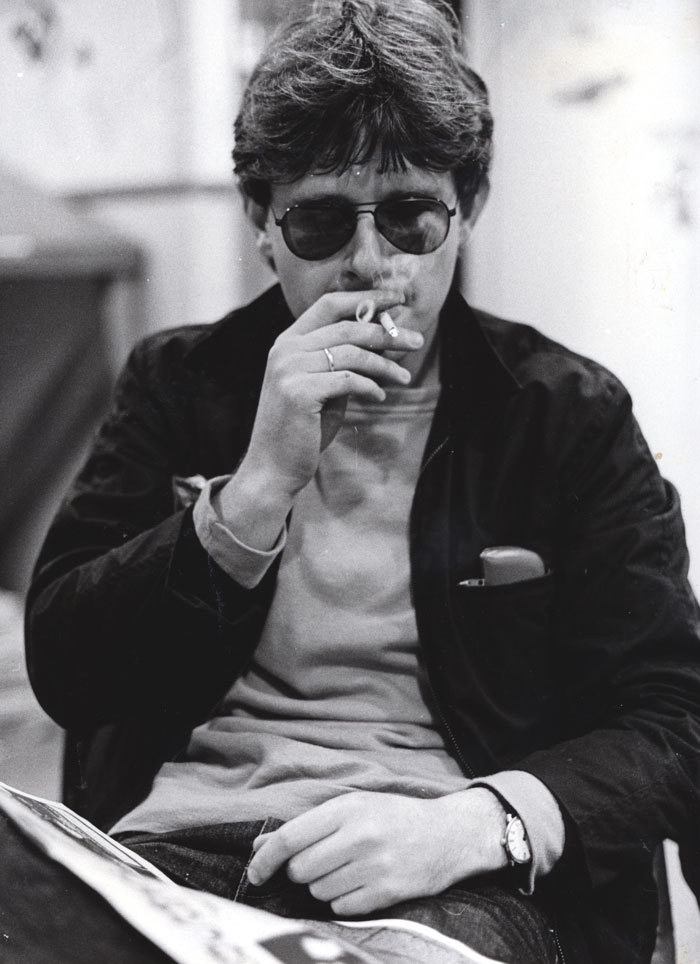

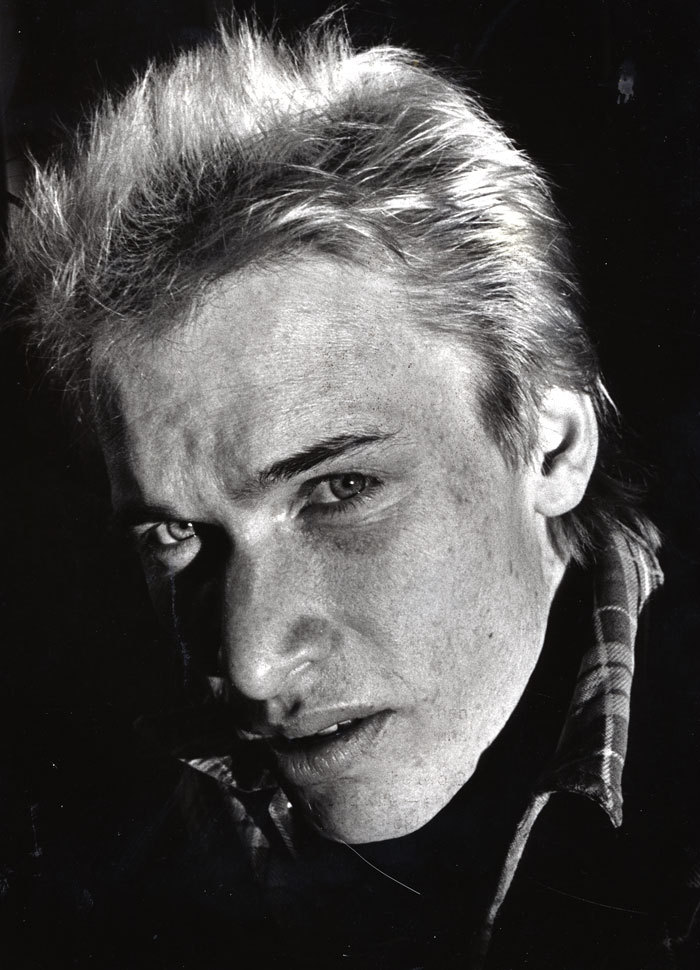

Gary Steel - Photo by Charles Jameson

This story isn’t all about me, though – it’s about the revolving-door collective of amazing writers, photographers and illustrators who gave of their time and talent for free over a six-year timespan and a magazine with a personality as big as its contributors. It does start with me, however, so please excuse the necessary introductory indulgence.

In adolescence, my whole being revolved around the rock revolution: the pulsing kaleidoscopic universe opened up by psychedelia.

The only subject I was ever good at was English, but I was never keen on Shakespeare, or the classics. In adolescence, my whole being revolved around the rock revolution: the pulsing kaleidoscopic universe opened up by psychedelia. But rather than making my own music, I preferred reading about it. The work of the beat poets and “gonzo” journalists, and finally, music journalists like Lester Bangs (who took their inspiration from those beat poets and gonzo journalists), seemed to me like the natural corollary to the music I was listening to. In the early 1970s, the American music magazine Creem, led by Bangs and his disciples, was devoured cover-to-cover by this pimply youth, in an attempt to uncover its secrets.

Creem represented a brief but hugely influential stand by writers to take control of the music to which they were listening – to become part of the creative act. This was no fanzine. While supine PR writers of fanzines put musicians/artists on a pedestal, the assumption of gonzo music writers was that they were of equal status, a very punk attitude to art and culture, one that assumed that the audience was integral to performance and art. Instead of participating in gushing fan worship or mere consumer guides, the Creem school of rock writers wanted their slice of the creative action, and each feature or review represented an analysis or hypothesis around the culture of music, but without any tedious hangover from academic essayists.

After several years of reading Creem, and then a revitalised New Musical Express (UK) that had employed a bunch of previously “underground” writers like Nick Kent and Mick Farren, as well as reprinting a lot of Creem stories, all I wanted to do was 1) Write about rock music, and 2) Start a rock magazine that focused on the cool bands and artists that those magazines never mentioned: the ones that came from where I came from, New Zealand.

Hotlicks, a mid-70s precursor to Rip It Up, put the idea in my head. Hotlicks had a radical proposition at a time of a crippling inferiority complex: that NZ-made music was on an equal footing to that from over the water. Not only that, but it occasionally ran stories backgrounding genres that were hard to get information about, like radical roots reggae, or the “motorik” grooves of “Krautrock”. It was the first publication that ever published my work, as a letter-writer with the nom de plume of “Captain Beefheart’s Greatest Fan.”

I just scraped through a yearlong journalism course in Wellington, and eagerly (albeit shyly) pursued a writing gig with the fledgling Rip It Up. I was amazed when editor Alastair Dougal commissioned me to write the monthly Wellington Rumours column, along with some album reviews, and a few features. I felt frustrated, though. To this naïve 19-year-old, Rip It Up seemed like the product of Auckland’s slick, commercial music industry, and I felt like they were more interested in stories on Sharon O’Neill than they were in the fertile Wellington post-punk underground. With the benefit of hindsight, I can see that Rip It Up’s editors, Murray Cammick and Dougal were simply following their passion for a more rootsy rock and roll and funk-edged coverage. My interests, contrarily, were towards the avant-garde edge of pop and rock, but that was in tune with the Wellington scene of the time.

Soon, despite being painfully shy, I was being jetted off to Auckland to interview Elton John and driven around in promoter Benny Levin’s Rolls Royce.

With an incredibly dull job as a junior sub-editor at the now-defunct Evening Post, my first dream came true when entertainment reporters Cameron Bennett and Hannah Wallis both left in quick succession, and I was asked to cover “that noisy stuff.” The fact that I had to do this in addition to my subbing duties, and that I wouldn’t be paid, hardly touched the sides. Soon, despite being painfully shy, I was being jetted off to Auckland to interview Elton John and driven around in promoter Benny Levin’s Rolls Royce.

My second dream came true in late 1979 when Evening Post sports writer Mike Aston approached me about starting an independent music magazine for Wellington. Aston was a hard-smoking, hard-drinking, old-school jock who joined the old hardliners from the newsroom daily for the beer swill at 2.30 – a hangover from the famous “six-o’clock swill”, which had been killed off in 1967. He had the technical know-how to get our magazine typeset and printed – a mindboggling and expensive pursuit in a time before computers as workstations – but also an agenda that would quickly put us at odds with each other.

Aston’s music aesthetic was, it turns out, firmly on the side of pub rock. He was born to love Cold Chisel and enthusiastically talked up any local group of new-wave copyists. As co-editors of In Touch (a god-awful name that still makes me cringe), we had completely different aesthetics, and in the year we shared duties, I had to accept unfeasibly long features on go-nowhere local bands like Bad Brakes and The Puppetz. The thing is, I wanted to plant a seed by covering local bands and push the idea that our own culture was valid, but not through indiscriminate patronage.

Still, we had a magazine (even if we had absolutely no running budget) and an audience enthusiastically embracing the free, more-or-less monthly publication and its predominance of stories and reviews on Wellington and South Island bands. In Touch was sporadically and poorly distributed outside of the Capital, and we had no real game plan and no business skills; we just had a desire to get the word out on music that we felt was being neglected by the monolithic newspapers and other media. And, of course, I had the implacable belief that writing about music should be more than mere reportage or promotion.

Gary Steel and Redmer Yska, In Touch offices - Photo by Charles Jameson

In 1980, In Touch was an amateurish and an aesthetic mishmash, but it did have some forward momentum, and its contributors poured love and creativity into its pages. And we were able to get into print for the first time stories on bands that might have otherwise fallen off history’s edges: the likes of the Ambitious Vegetables, The Steroids, Shoes This High, The Wallsockets, Life In The Fridge Exists, and The Gordons.

Redmer Yska, May 1981 - Photo by Charles Jameson

I don’t remember how it happened, but by 1981, I was in sole charge of In Touch, and with new co-conspirator Redmer Yska the magazine found its true calling. Yska had worked for The Truth when it was still an influential news tabloid, and knew how to boil a story down to its essential fatty acids. And what a story we had that year: the Springbok tour and the unrest it generated, and a political climate, centred on the Capital, that perfectly shadowed the new underground sounds of bands that we chose to expose. As Yska says, “It was all about Joy Division. They were the glue.” We championed the new wave of English bands like JD, The Cure, The Fall and Echo & The Bunnymen – bands whose music spoke to us through a mist of manic depression and alienation. And in Wellington, we championed Naked Spots Dance, Smelly Feet, Beat Rhythm Fashion, the early Flying Nun bands, and the more creative Auckland groups like The Features/ Fetus Productions and Blam Blam Blam. Yska’s instinct for good non-music stories also saw In Touch writing about relevant subjects on the edge of the music scene, like his story on the events leading to the suicide of boot-boy Rhys Bassett, and Neil Roberts, the chap who blew himself up outside the Wanganui Computer Centre. It was a dark time in NZ history, but In Touch, at least, captured that zeitgeist.

Gary Steel and Redmer Yska, June 1981 - Photo by Charles Jameson

Gary Steel and Peter Avery - Photo by Peter Avery

Redmer Yska, May 1981 - Photo by Charles Jameson

By the end of 1982, Yska was drifting off to more financially rewarding pursuits, while still contributing the odd story or review. Emboldened by a new generation of glossy British pop culture magazines like The Face and Blitz, the idea was hatched to evolve the magazine into IT (in honour of the radical late 60s underground magazine), sell it for the princely sum of $1, and support it with a fortnightly “what’s on” arts and entertainment leaflet, TOM (The Other Magazine). Inevitably, IT got left behind when it turned out that TOM would be all-consuming in time and energy, and the publication would rock along for another two-and-a-half years before the wheels fell off for good.

Sherryn Congden (vocalist with Wellington band Domestic Blitz), Helen Collett, Dave McLennan and Gary Steel - Photo by Charles Jameson

Peter Avery at Colin Morris Records, 1983, having just delivered the new In Touch

The magazine had been dealt a lethal blow by bureaucratic reaction to a quote from expat jazz pianist Mike Nock.

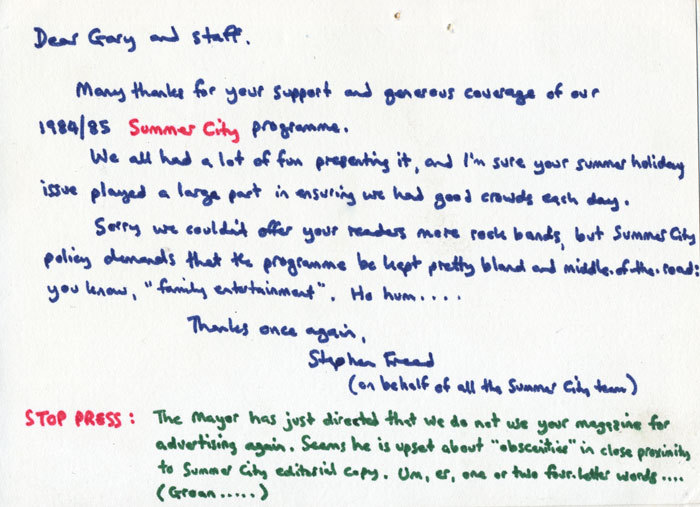

By mid-1985, I was struggling to keep my head above water, and the magazine had been dealt a lethal blow by the bureaucratic reaction to a quote from expat jazz pianist Mike Nock, in which he infamously called Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, “a fucking money-grabbing bitch.” Ironically, the feature on Nock, written by Ken Double, hardly drew a peep on its first pass. It was at the end of 1984 in our “best of year” issue, in which Steve Braunias had gathered together the best quotes from the magazine, that the offending passage did its damage. There were complaints from concerned members of cultural institutions to the then-Minister Of The Arts, Peter Tapsell, who wrote a stern letter reproving us for our indiscretion. But the killing blow was when the Mayor’s Office reacted by retracting a whole summer’s worth of full-page ads – ads that the magazine badly needed.

The director of the Wellington Cultural Centre writes ...

The Mayor writes to the Town Clerk ...

The Director of Parks & Recreation writes to the Town Clerk ...

The Minister For The Arts weighs in ...

The Mayor writes ...

I loved doing those magazines and would have vivid dreams about them for years to come, only to wake up and be thrust into a future in which they no longer existed.

I never earned a wage from In Touch or TOM, and I don’t remember any contributors being given anything but free records to review. The magazine operated in a succession of dire, cold, unhealthy offices, most of them now demolished. One was in a dank, dark, airless space in the basement of a warehouse under Bryan Staff’s then-residence. Another had broken windows, so the pigeons were always getting in and shitting on everything. At one stage, we were unlucky to be right next to a breakaway karate group with violent tendencies. They ended up breaking our door down while we were out, just because they wanted to menace us. Yska reminded me of one office where the rain came through the ceiling and leaked all over our layout pages. I don’t remember it, but he says that I phoned the landlord and told him: “I’ll pay the rent when our chequebook dries out.”

Gary Steel - Photo by Charles Jameson

Production was always a challenge, too. It would cost upwards of $1000 just for the typesetting, and the conservative Christian typesetters made so many (intentional?) errors that it cost money and time. They would eliminate swearing or change words at will: a couple of manglings that still amuse me include “Tony Lover” (Toy Love) and “Joy Davidson” (Joy Division). Happily, by the time TOM came along, I was working at NBR as a part-time typesetter, so I was able to churn out my own pages on the sly.

Despite the ongoing difficulties, the magazine/s will always remain special to me because of the amazing contributors who clustered around and gave their best for free. I’ve always maintained that a magazine is like a person – it’s a personality that readers might love or hate, but it must have character to make its mark. The long list of talent associated with In Touch and TOM mean that it was seen as a vehicle for something special, and that means a lot to me.

Peter Avery by Peter Avery

We had two extraordinary photographers, Charles Jameson and Peter Avery, both of whom had day jobs with Wellington newspapers, and both of whom took some of the most iconic shots of both local and touring international acts between 1980 and 85, many of them sadly now lost. Then there were the writers whose formative work In Touch and TOM introduced: Helen Collett, David Cohen, Garth Cartwright, Redmer Yska, Steve Braunias and many others. The likes of Ruth Laugesen, Russell Brown, Jane Clifton, and Mark Cubey also had brief liaisons with the magazine.

Gary Steel and Steve Braunias - Photo by Peter Avery

It was a time when it was still possible to interview major stars on our terms, so we had Helen Collett hanging out with New Order and folding their laundry, Helen Collett drunkenly arguing with Ian McCulloch after Echo & The Bunnymen’s Palmerston North gig, two infatuated schoolgirls interviewing The Police, and all of us hanging out with The Cure at David Maclennan’s flat.

So then, a belated thank you to everyone whose input made a difference to In Touch and TOM, especially Ken Double, who so valiantly slaved over the TOM design (while also contributing fine words), and to Redmer Yska and Steve Braunias, whose sharp, incisive and often hilarious copy made the publication memorable (not to mention contentious).

The TOM team: Gary Steel, Jenny Murray, Charles Jameson, Steve Braunias, Hellen Collett

I don’t think there’s ever been a Kiwi freebie quite as gutsy as these wee mags, and I can’t imagine them surviving today. In short, we pissed off our advertisers because our reviews were unflinchingly honest. How naïve of me. But I never regretted sticking to my guns, and most of the participants in this little passion play have gone on to great things.

Magazines age only marginally better than newspapers, but I’m happy to know that there’s a cache of information buried in the pages of both In Touch and TOM about local bands from the era that adds to the collective history. There was a lot going on in Wellington between 1980 and 1985, but there’s surprisingly little to show for it in terms of recordings. Hopefully, when reviews of obscure Wellington groups start to emerge, there might be a little spike in the availability of long-lost – or even never-before-released – treasures.

In Touch and TOM highs and lows

March 1980 In Touch debuts with Sweetwaters festival cover, its first editorial stating: “You will notice a predominance of local material: NZ groups, Wellington concert reviews. We make no apologies for this.” And our mission statement: “In Touch is a music newspaper dedicated to fostering a greater awareness of the Capital’s music scene.”

April 1980 editorial “With concerts from jazz aces Brubeck and Liebman, the British National Youth Jazz Orchestra, Racey, the Pointer Sisters, Fleetwood Mac, John and Sharon and two from Enz, 1980 is certainly looking very good.” Groan. And someone called Gary Steel predicted that Flight X7 was going to make it big.

May 1980 features a fetching Gary Numan illustration by Paul Hargreaves (where are you now?) and the debut of Dave Mclennan’s singles column. David boasts that he has seen Toy Love perform 17 times. I remember some wag sprayed the graffiti message: “Dave Mclennan wears pyjamas.”

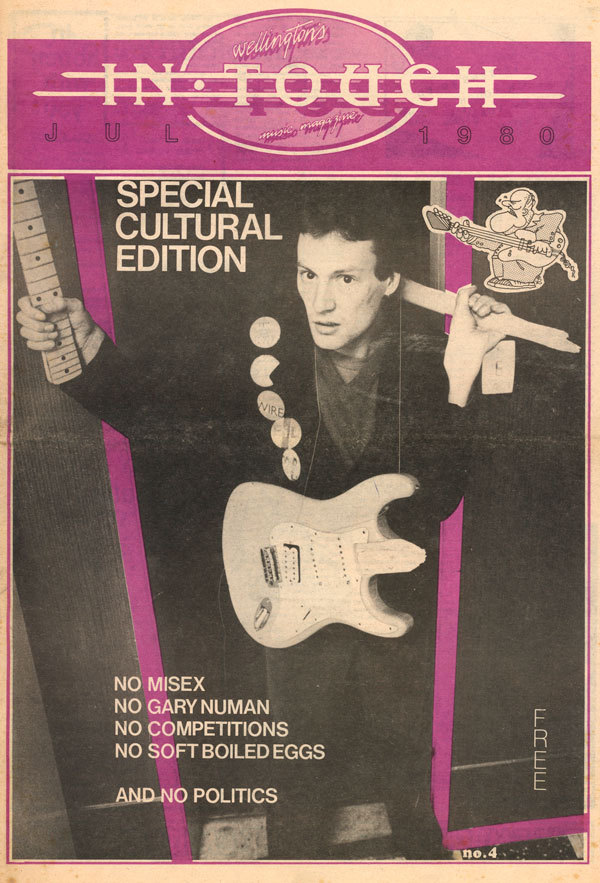

July 1980 bares the cover lines: “No Mi-Sex, No Gary Numan, No Competitions, No Soft Boiled Eggs”. I have no idea what that means. My piece on The Steroids made the cover. Staying temporarily with my parents in Island Bay while recovering from a bout of glandular fever, I remember Alan Jansson picking me up and taking me to his flat, but the rest of the session is a void. I vaguely remember being delivered back in a very altered state.

August 1980 improbably features both The Wallsockets and Jon English on the cover, a perfect example of the magazine’s dichotomy in its first year.

April 1981 debuts the new, A4-sized mag with Redmer Yska on board: suddenly, it’s sharp, funny, and relevant. A couple of adoring schoolgirls, Erica and Juliet Roberts, got to interview their heroes, The Police.

June 1981 My Evening Post campaign to get Joy Division released in NZ finally comes to fruition with RTC belatedly issuing the 12-inch EPs and albums locally. And they took full-page ads.

December/ January of 1981 and 1982 is best summed up by Redmer Yska’s “Bricks & Bouquets For 1981” piece:

“Joy Division knee-capped 1981. I still remember chatting to Tony Proton perched in a Willis St sandwich bar, who jokingly told me all his friends were now tying their shoes in a Joy Division way. Kiwis really took both albums to their hearts in much the same way the Cure got there last year. Closer and Unknown Pleasures captured a mood like one of those katipo spiders in Perspex. That memorable letter to In Touch from an Auckland reader, which spoke of the ‘positive relief of tension’ that Ian Curtis’s voice gave him, explained it all. Can you remember hearing the glistening ‘Atmosphere’ on top of the Ready To Roll charts seconds before more bulletins from another blood-spattered Springbok clash on the 6.30 news? Balm for a troubled land.”

April 1982 featured a cover story on The Spines, whose Jon McLeary provided the cover illustration.

May 1982 The final In Touch featured Anna Crichton’s wicked illustration of a shit-spattered new romantic pig, and Redmer’s bitter, disenchanted piece on that “movement” that had usurped the post-punk revolution.

IT, which sold for $1 and did quite well, featured a cover story on the Nun’s Of Perpetual Indulgence, Helen Collett on The Fall and the debut of Steve Braunias.

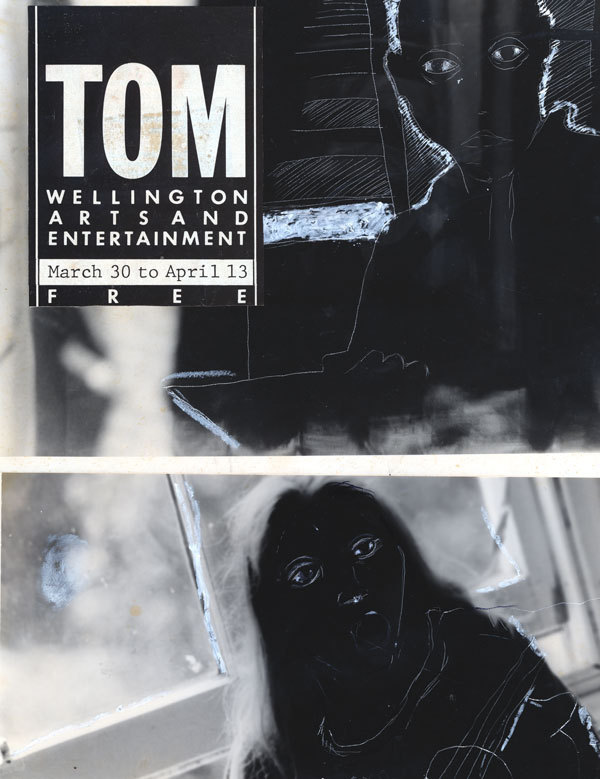

TOM March, 1983

March 30 1983 TOM debuted with a Charles Jameson cover of a (supposedly) wrecked Steve Braunias, thematically linked to what would be an enormous ongoing feature on local venues/pubs.

May 27 1983 Steve Braunias interviews Gerald Dwyer (Flesh D-Vice) and Void (Riot 111).

August 5 1983 Helen Collett’s Fishschool feature and Jane Walker’s Fishschool illustration on the cover.

September 12 1983 Helen Collett on Bill Direen and Steve Braunias on Karyn Hay.

September 30 1983 Helen Collett on The Great Unwashed.

October 14 1983 The Gordons cover story by Steel.

October 28 1983 Steve Braunias on Body Electric.

November 25 1983 Void on cover. Story on Neil Roberts, the chap who blew himself up at the Wanganui Computer Centre.

May 25 1984 Braunias feature on independent cassette labels, and Ken Double’s eventually explosive Mike Nock feature.

July 20 1984 Steel and Collett double-date interview of The Great Unwashed.

August 3 1984 Gerald Dwyer on Motorhead.

Roll call of contributors

Jane Clifton (later a longterm political columnist for the NZ Listener), Peter Cathro (photographer/ television), David McLennan (astronomy expert and rigorous musical trainspotter), Helen Collett (later to have a memorable column in the Sunday Times, and disappear off the radar – New Zealand’s answer to Julie Burchill), Jenni Raynish (of successful PR firm Raynish & Associates), Malcolm McSporran (later to edit NZ Rolling Stone and work for a number of arts associations), Russell Brown (the ubiquitous), Garth Cartwright (then a 16-year-old Mt Roskill kid; now a respected London-based music/culture author), Anna Crichton (illustrator), Steve Braunias (later a Metro feature writer and respected author), Ken Double (art direction and words, now a distinguished advertising agency chap), Warren Mayne (RIP), Warren Lasky (dense mindfloss), Ron Kane (occasional American correspondent), Anthony McCarten (playwright), David Cohen (once a music journalist, now a distinguished political commentator and author), Zak Reddan (constant ADHD inspiration, pop culture expertise, now works for the Film Archive), Adam Gifford (now a freelance journalist), more …

Gary Steel - Photo by Charles Jameson

Links

Gary Steel is slowly digging up and making available odds and sods from In Touch and TOM on his website witchdoctor.co.nz

The Spines

Dave Dobbyn

The "four stars" (****) album

The Gordons