From its foundation in the early 1970s to its finale some 20 years later, the New Zealand Student Arts Council was behind some of this country’s most memorable tours and helped establish an audience for local touring acts. The NZSAC archives, held in the JC Beaglehole Reading Room at Victoria University of Wellington Library, conjure a vivid pictorial record of those musical years.

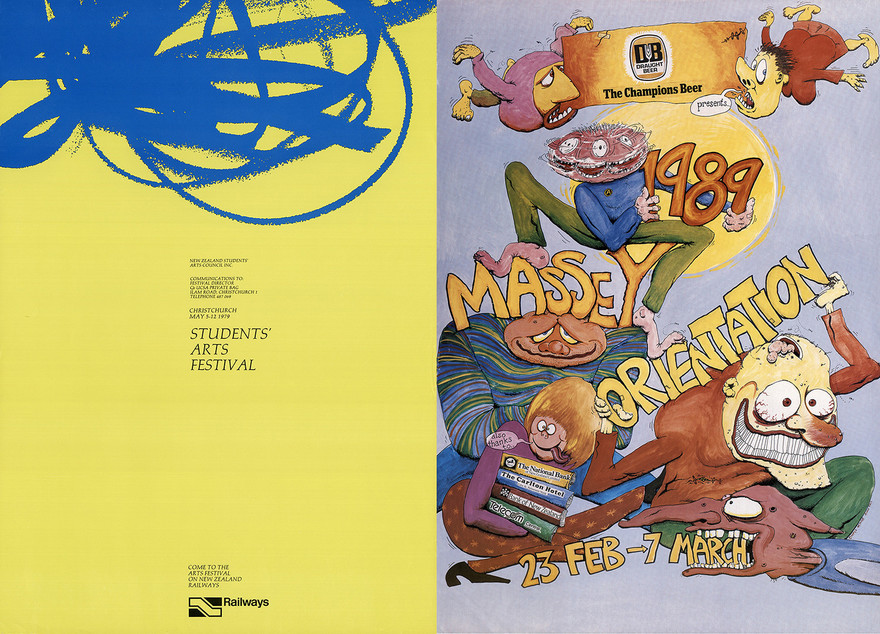

Student Arts Council posters for (left) the 1979 Students’ Arts Festival, and Massey University Orientation, 1989. The sponsors are very meat’n’spuds: New Zealand Railways and Dominion Breweries. The 1989 Massey poster is by Chris Knox.

The New Zealand Student Arts Council had its origins in sports administration. As far back as 1941, the annual Universities Winter Tournament included a drama festival as part of its programme. But concern that the New Zealand University Students Association was overly focused on sport led to a proposal for a standalone arts festival. The first Students’ Arts Festival took place in Dunedin in 1959, and Canterbury followed the next year. These were so successful that an Arts Festival schedule was added to the New Zealand University Students’ Association constitution.

In 1966 the New Zealand Universities Arts Council was created. In 1970 a levy per student member was introduced to allow the Council to budget according to its own criteria, subject to the final approval of the Students’ Association.

Initially the Student Arts’ Festivals featured a mixture of drama, film, poetry, games (chess was big), law moots, and music – usually classical, folk, or jazz. Anything resembling rock was confined to a “hop” on the Saturday night. Things began to change with the 1968 event, held in Auckland: the traditional hop was replaced with a “Freak Out” featuring a live rock band and psychedelic lighting.

But the turning point came with the 1970 festival in Wellington. It began with an early morning rock show by Mammal in the foyer of Wellington Railway Station, featured campus shows by Triangle, Gutbucket and Pussyfoot, and climaxed with a concert in the Paramount Theatre by the recently formed Wellington “supergroup” Highway. “The best local thing I’ve ever been to,” enthused Auckland student Bruce Cavell in Craccum. “Rock’n’roll played the way you wish it would always be played.”

In 1971 it was Canterbury’s turn to host the festival, and Canta was reporting that “the newest and now the biggest event in Art Festival is blues /rock”, while noting that “the first two days were plagued by PA problems which fouled up several groups … A Wellington group Rick and his Rockets [sic] booed off at the Tuesday concert (give us an F) improved vastly during the week to be welcomed onto the stage at the end …”

For the Canta reviewer the “sensation of the week” was Australian band Daddy Cool, an offshoot of Melbourne progressive rock band Sons of the Vegetal Mother specialising in 50s style rock’n’roll.

“Daddy Cool were probably a sign of the future. Festivals will from now on undoubtedly have star imported attractions – not big-name commercial successes but progressive groups beginning to make a name for themselves. There is a danger however in having these special features, as they could reduce the festival to a mere stage prop for a pop show.”

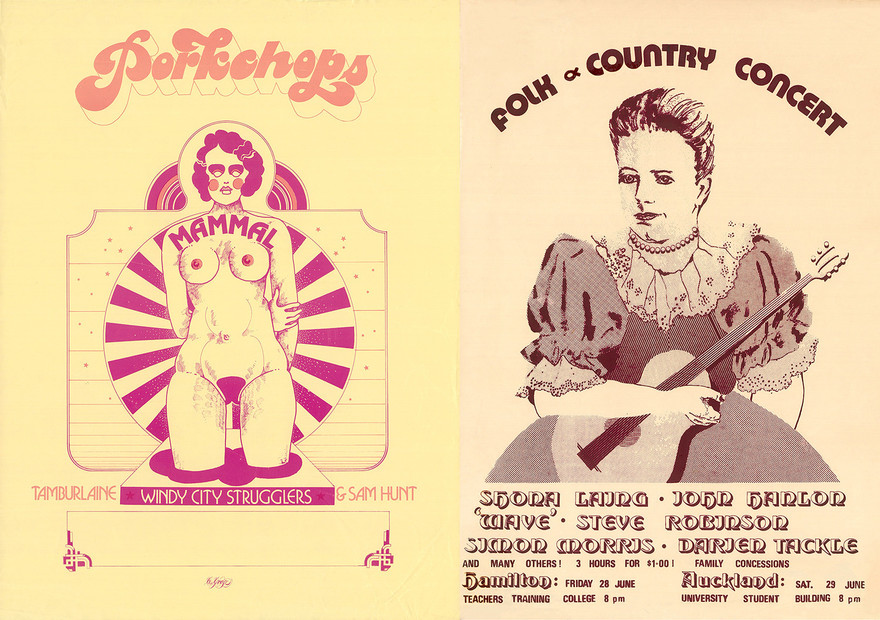

Porkchops: a concert featuring Mammal, Tamburlaine, the Windy City Strugglers, and poet Sam Hunt (poster by Chris Grosz, circa 1972). Right: Shona Laing and John Hanlon top the bill at a Folk & Country concert, June, 1974.

By 1972, the New Zealand Universities Arts Council had grown to include all tertiary institutions and the name was changed to the New Zealand Students Arts Council, with Graeme Nesbitt, who had been controller of the 1970 Arts Festival, appointed part-time as its first director. A musician himself, Nesbitt began organising folk concerts on the Victoria University campus in the ’60s, and was closely involved with bands such as Mammal, Tamburlaine and the 1953 Memorial Rock & Roll Band (led by the Red Hot Peppers’ Robbie Lavën). Nesbitt oversaw campus tours by these and other bands, as well as the American protest singer Phil Ochs, who was double-billed with the political cartoonist and activist Ron Cobb.

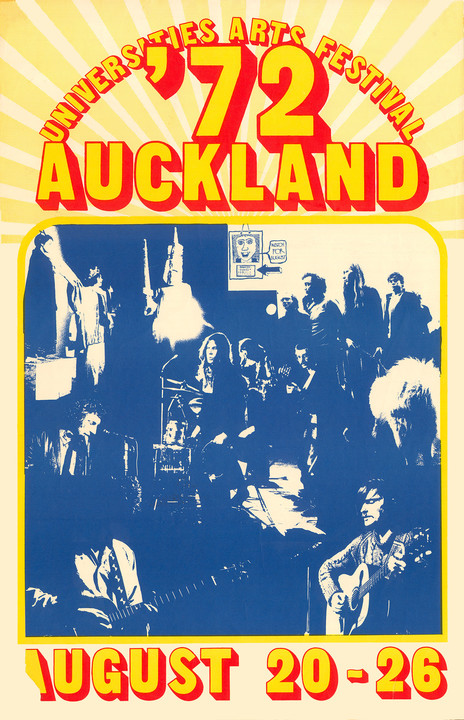

A poster for the 1972 Students Arts Festival, held in Auckland.

In 1973 Bruce Kirkland was appointed first full-time director, and the Council expanded its national touring programme, kicking off with a campus tour by veteran US bluesmen Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, followed by the Aboriginal Dance Group. Often working in collaboration with Nesbitt, Kirkland maintained the policy of hosting acts with an alternative edge. That year Split Enz, in their early vaudeville-gothic phase, undertook their first campus tour.

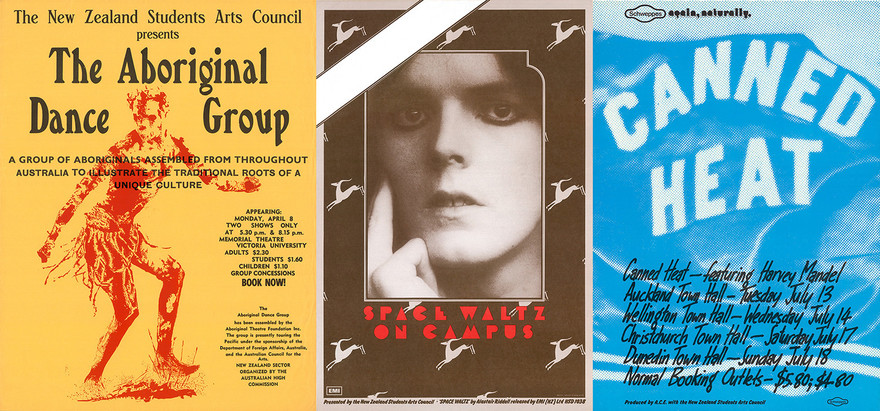

Student Arts Council posters: the Aboriginal Dance Group, 1974; Space Waltz, 1975; US boogie band Canned Heat, 1976.

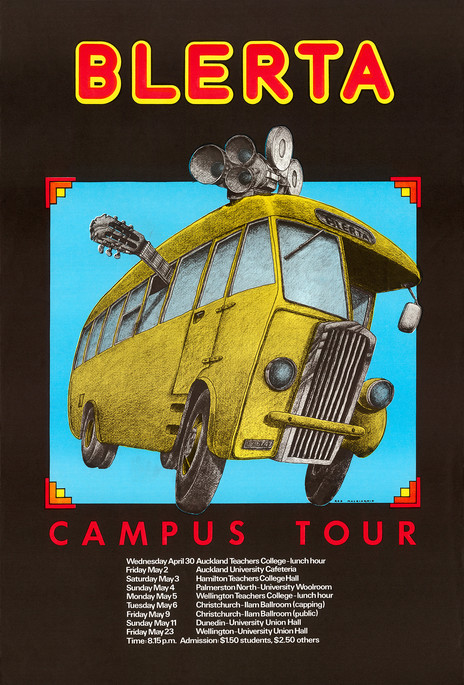

Other internationals who toured under Kirkland’s aegis included boogie-blues band Canned Heat, comedy rockers Flo and Eddie, and American folk singers Tom Paxton and Country Joe McDonald, while homegrown travellers included Alastair Riddell’s Space Waltz on their first national outing, BLERTA (recently returned from two years in Australia), and the Red Mole theatre troupe.

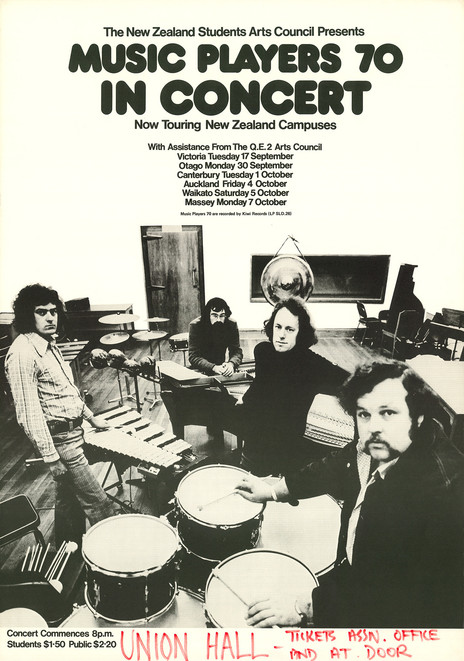

Contemporary classical and experimental music was represented in Sonic Circus – a multi-media happening held at Victoria University – and a national tour by Music Players 70. The latter required one and a half tons of percussion equipment which had too be moved around the country.

Music Players 70 was a New Zealand chamber quartet active in the early 70s. At first, it featured two pianists and two percussionists: Trevor Dean, Barry Margan, David James, and Gary Brain.

Kirkland also headed a visionary project bringing touring acts into prisons. In August 1973 a proposed package including poet Sam Hunt, the Beggars Bag theatre group, singer Jenny Parkinson (from the Australian production of Hair) and the 1953 Memorial Society Rock’n’Roll Band was sent to the superintendents of the country’s penal institutions. With a $3000 grant from the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council, a two-week prison tour went ahead shortly before Christmas.

Sometimes NZSAC would collaborate with other promoters. When veterans Benny Levin and Russell Clark brought Little Feat to New Zealand in 1976, NZSAC was able to offer students preferential booking at a discounted price.

There were moments when the tastes of the students, particularly on the provincial campuses, appeared to be out of step with those of the NZSAC programmers. A letter to Kirkland from Alison Mander, cultural vice-president of Massey University in Palmerston North, reflects on the small turnout for a 1975 BLERTA show. The publicity, she said, had been inadequate due to the late arrival of posters. But “the second reason is that no matter how well the thing was advertised, people here are anti-BLERTA. Towards the beginning of the term BLERTA came here to give a dance-type concert which turned out to be one of those where the group and the audience did not like one another. The audience had decided they wanted to dance but BLERTA wanted them to sit and listen for a while. Which was unfortunate and explains why only 165 were willing to give them a chance this time.”

The poor turnout can’t have been helped by a preview that appeared the week before in Chaff, the Massey student newspaper, which stated: “This will be concert not a dance, so unfortunately it looks like you’re going to be expected to watch and listen … be prepared for numb backsides at the end of the evening!”

“Numb backsides”: BLERTA tours nationwide in 1975.

Though NZSAC spread its attention across the art forms, there was continual disquiet about the degree of focus given to rock tours, and the financial losses these sometimes incurred. Bruce Kirkland resigned at the end of 1976, and went on to a very successful career in the international music industry, joining promoters Evans Gudinski in Melbourne before moving into management roles at Stiff Records in London and New York. He later founded his own company Second Vision, representing artists such as Peter Gabriel; in 1993 he became general manager / senior vice president of Capitol Records, Los Angeles.

Kirkland was succeeded as NZSAC director by Paul Davis, who was followed in 1981 by Gisella Carr. The role was subsequently held by Briony Ellis (1984-86), Roger Wood (1986-1987), Sue Dempsey (1987-1989) and Marcia Murphy (from 1989 until the Council’s demise in 1992).

In 1977 the Council separated from the New Zealand University Students Association and became an Incorporated Society in its own right. It was then an autonomous body with over 140,000 individual members from universities, teachers colleges, technical institutions and community colleges throughout the country. The late 70s saw tours by British folk innovators John Martyn and Bert Jansch and the most successful NZSAC tour so far by a local group, Hello Sailor.

Hello Sailor toured nationwide for the Students' Arts Council, 1978.

Correspondence in the NZSAC files shows how the tours became more sophisticated over time. A letter from Bruce Kirkland to the various campuses hosting a two-and-a-half week 1973 tour by Tamburlaine, Mammal and Sam Hunt requests that the hosts provide floors and mattresses for the musicians, who will be bringing their own sleeping bags and blankets. Five years later, the itinerary for a Hello Sailor campus tour looks less like a school camping trip and more like a professional rock tour, with travel by plane and minibus, and hotel accommodation rather than the floors of campus common rooms.

Bands could also make use of an arrangement between NZSAC and New Zealand Railways, allowing them free travel on trains and ferries, a particular advantage for acts crossing the Strait.

Student Arts Festivals continued to bring diverse musical packages to the campuses for the remainder of the 70s – sometimes too diverse, as in August 1977 in Wellington when Auckland’s first punk bands The Scavengers and the Suburban Reptiles were inappropriately double-billed with Hare Krishna devotees Living Force. The resulting turmoil is documented elsewhere on this site.

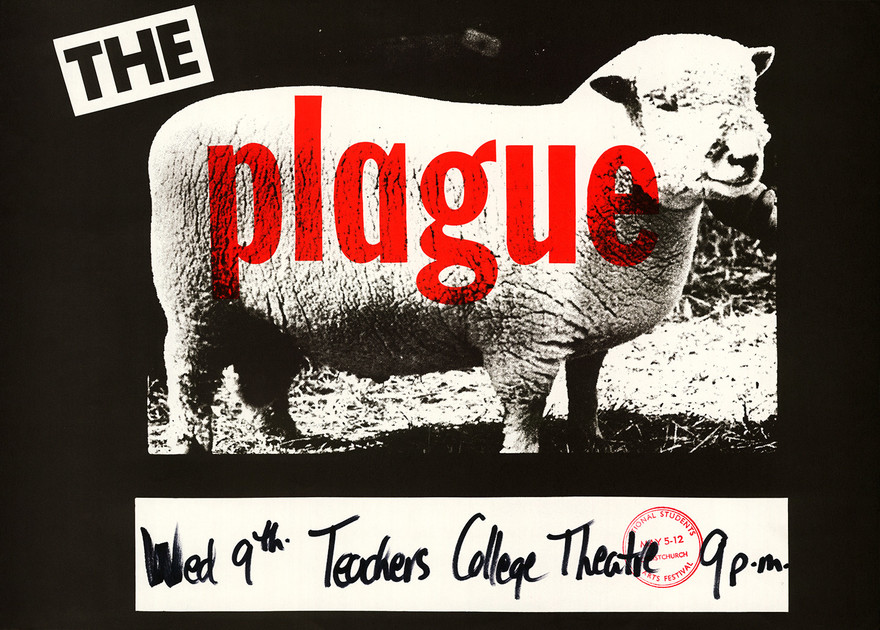

Including future members of Blam Blam Blam, The Swingers and Coconut Rough, The Plague brought their confrontational blend of punk, poetry and theatrics to campuses in 1979, including a performance at Wellington Teachers College.

The 1979 Students Arts Festival featured The Plague, whose talents spread to Blam Blam Blam, the Swingers, and Coconut Rough.

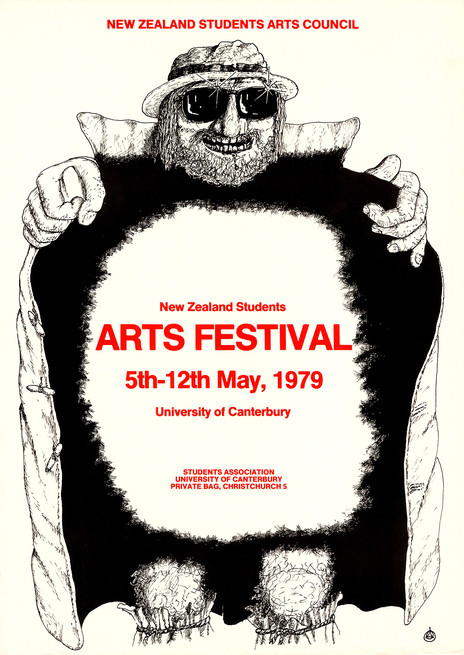

The final Student Arts Festival was held in Canterbury University in 1979, after which Orientation took over as the annual showcase for musical variety.

The poster for the final national Students Arts Festival, held at the University of Canterbury in May 1979.

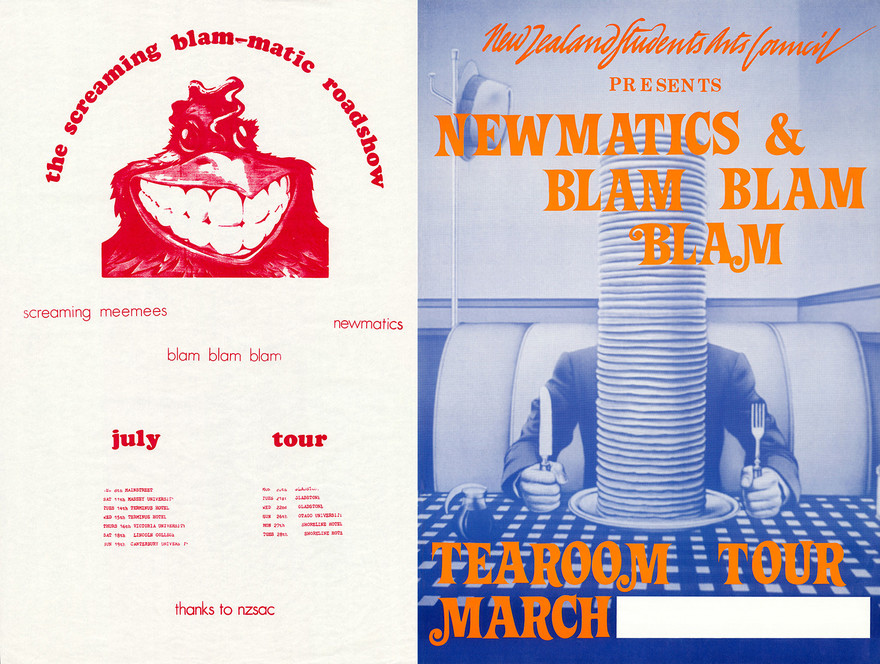

For Orientation in 1981 a triumvirate of Auckland bands from the Propeller label – Screaming Meemees, Blam Blam Blam and The Newmatics – hit the state highway as The Screaming Blam-matic Roadshow.

The "Screaming Blam-matic Roadshow" of 1981 drew some violence from boot boys in the audience. The Newmatics and the Blams followed with a "tearoom tour".

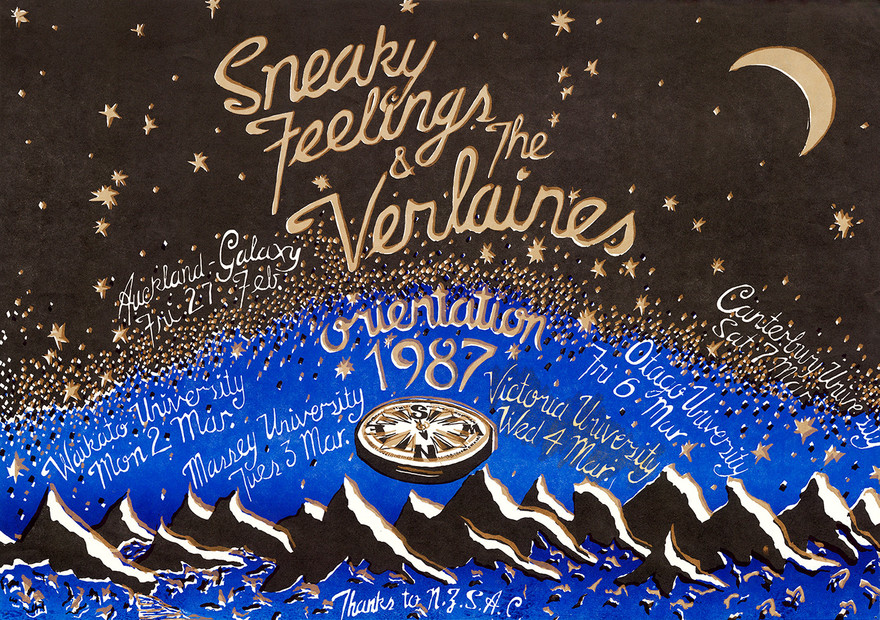

Subsequent years would see a punk-ska alliance with a package of Instigators, Riot 111 and Desperate Measures (1982), and several conglomerations of bands from the Flying Nun label, including Tall Dwarfs and The Clean (1982); Sneaky Feelings and Look Blue Go Purple (1986); Sneaky Feelings and The Verlaines (1987), and Bailter Space, Snapper, Headless Chickens and Straitjacket Fits (1989).

Flying Nun's Sneaky Feelings and the Verlaines embarked on an Orientation tour for the NZSAC in 1987.

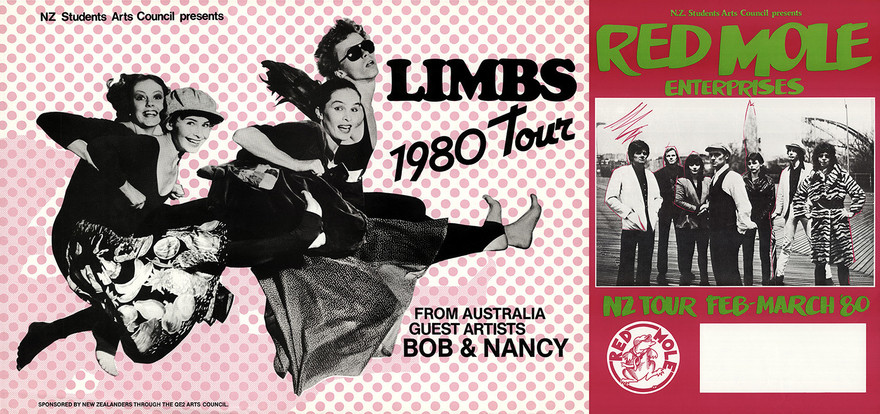

Throughout this time, NZSAC continued to tour other art forms: dance and theatre shows, photographic exhibitions, painting, and sculpture. Frequent favourites were the pioneering contemporary dance company Limbs and the underground theatre troupe Red Mole, both of whom would collaborate with rock groups.

NZSAC tours with a wider interpretation of the arts: Limbs and Red Mole, both in 1980.

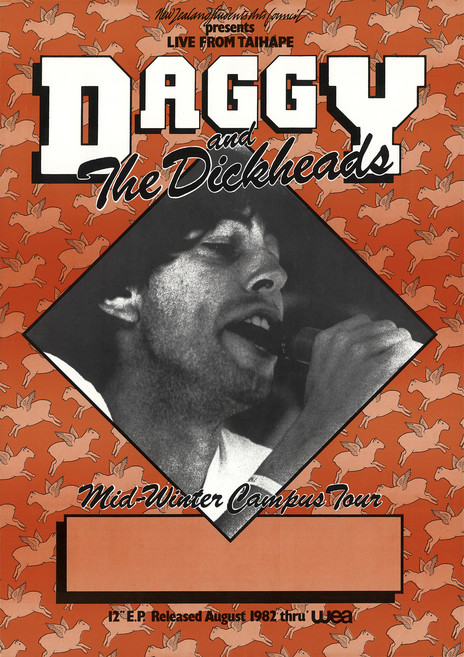

If there were occasional mismatches between artist and audience – BLERTA’s Massey fiasco being a prime example – there were also times when an audience was unexpectedly won over, as during the Dunedin visit of Daggy and the Dickheads during a two-week nationwide campus tour in 1982.

Taihape's Daggy and the Dickheads won over the nation's students in winter 1982.

Noting that “the five bandmembers are farm workers from Taihape”, the journalist for Otago campus newspaper Critic confessed that “frankly I was sceptical about Daggy and the Dickheads.” Yet he was pleased to discover that the band were “nothing like the black singlet and gumboot clad gents I had expected. No tanalised fenceposts these boys.” In conclusion, he wrote: “May Daggy and the Dickheads return often, develop promisingly and be more successful than Fred Dagg.”

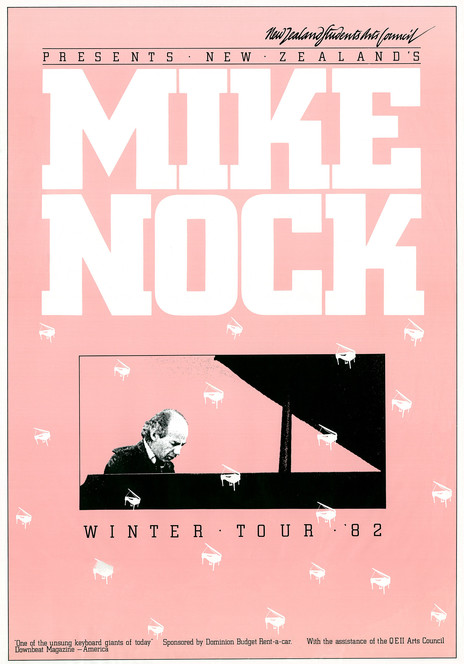

Also in the winter of 1982, expatriate jazz pianist Mike Nock came home for a series of concerts reuniting him with some of his New Zealand-based contemporaries such as bass player Paul Dyne and drummer Roger Sellers.

After his 1982 NZSAC tour, Mike Nock began to return home for concerts more regularly. Note the similarity in design with the poster above: flying pianos vs flying sheep.

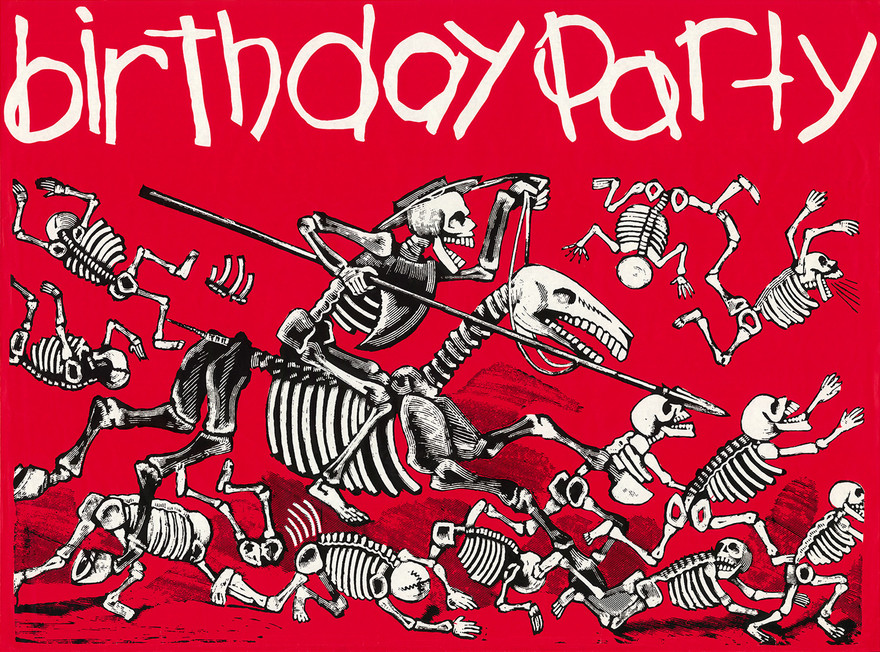

In 1983, Australian post-punk disturbers The Birthday Party, in the throes of disintegration, hit the campus trail with a suitably apocalyptic poster to herald the oncoming mayhem.

The Birthday Party's 1983 NZSAC tour did not feature any tearoom visits.

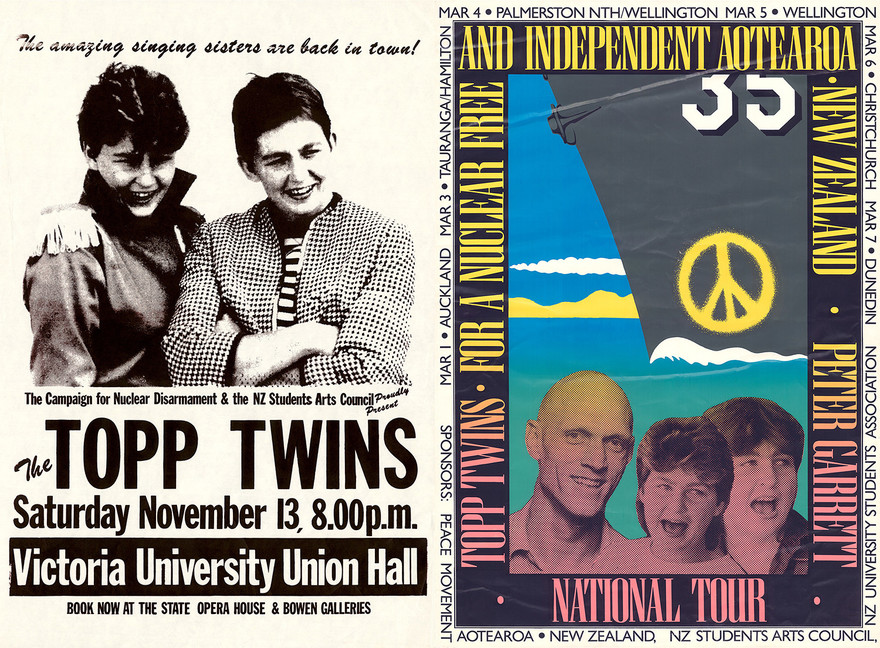

The early 80s also saw several NZSAC tours by the popular and political Topp Twins. In 1985, with the nuclear-free issue coming to a head, the Twins were paired with Midnight Oil singer and political activist Peter Garrett for a combined speaking and singing tour to promote the anti-nuclear cause. The tour was a combined effort of the NZSAC and Peace Movement Aotearoa.

The Topps Twins on campus in 1982, and in 1985 with Midnight Oil's Peter Garrett. The 1985 tour was organised by Peace Movement Aotearoa, with the NZ University Students Association and the NZ Students Arts Council.

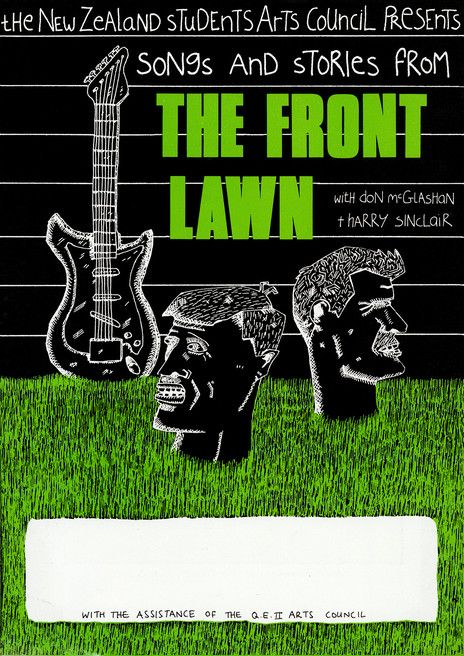

Blam Blam Blam’s Don McGlashan and actor Harry Sinclair followed in the multi-media tradition of trailblazers like BLERTA, combining theatre, music, and social satire in The Front Lawn.

Songs from the Front Lawn tour, 1985: NZSAC in combination with the QEII Arts Council.

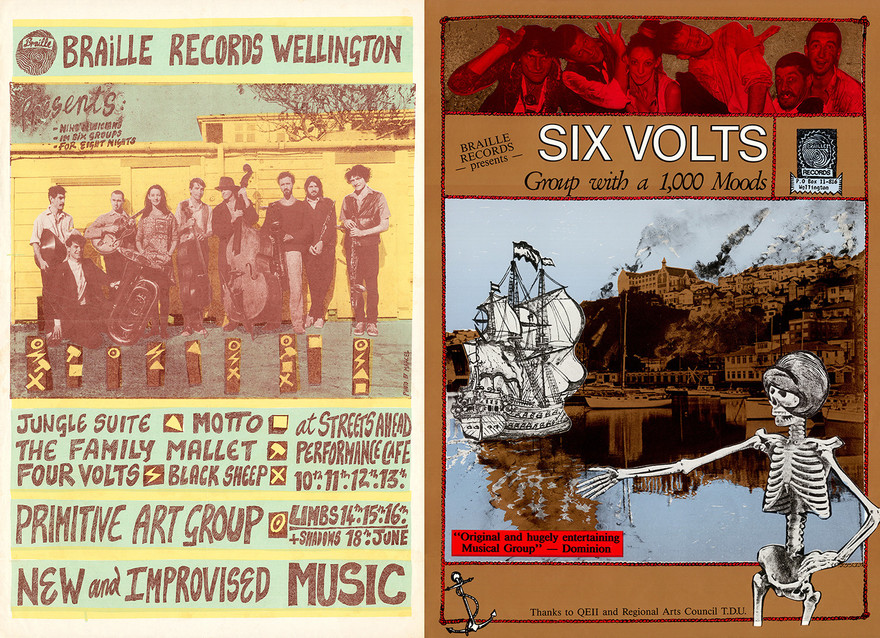

Members of Wellington’s jazz and experimental music collective Braille popped up in various incarnations, such as the Primitive Art Group and Six Volts.

A Braille package tour, 1986; the Six Volts tour, 1989.

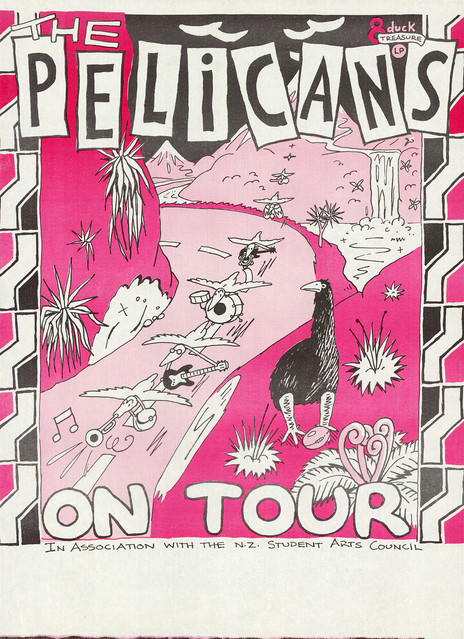

A national orientation tour saw capital funksters The Pelicans taking full advantage of NZSAC’s travel deal with New Zealand Railways, hence the prominent use of the NZR logo in their poster design.

The Pelicans catch the midnight train, 1985. Illustration by Tim Bollinger.

Despite many notable successes, the Council continued to face criticism for its perceived practice of supporting concerts and tours at the expense of campus-focused cultural activities, leading to Canterbury University withdrawing from the Council in 1984. As a result, the Council went through a period of restructuring to bring the focus back to local campus activities.

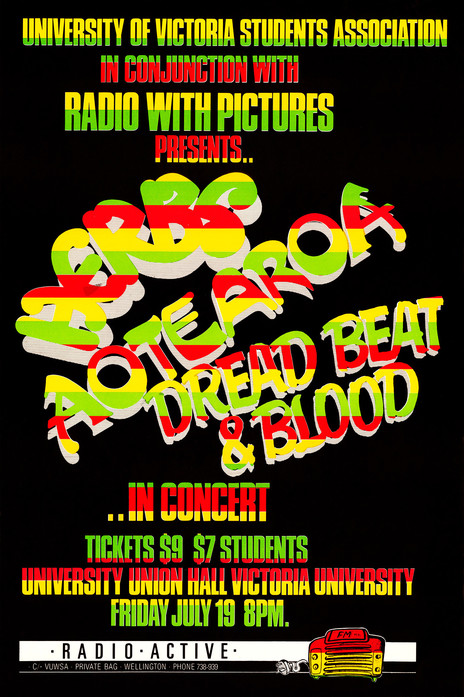

A 1985 televised concert capturing the explosion of local reggae, showcasing Herbs, Aotearoa, and Dread Beat and Blood, was undertaken by Victoria University’s Students Association in conjunction with Television New Zealand.

The best of New Zealand reggae, filmed on campus for Radio With Pictures, 1985.

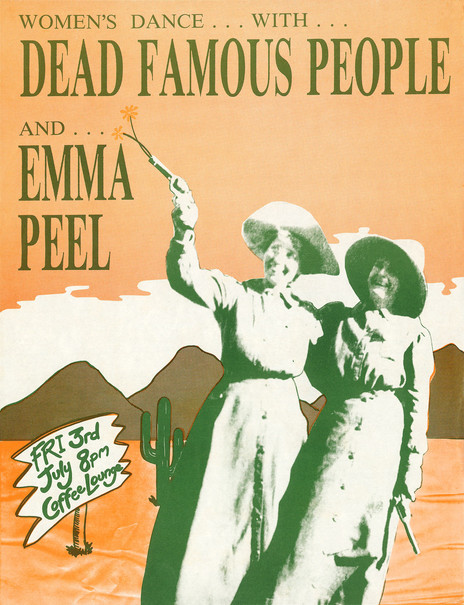

Dead Famous People and Emma Peel: a women's dance, Auckland University, 1987.

During this time NZSAC supported several national projects promoting Māori language and performance, including tours by Māori theatre collective Te Ohu Whakaari and bilingual reggae band Aotearoa.

Māori theatre collective Te Ohu Whakaari toured seven centres for NZSAC in 1986. At this stage, its members were Tina Cook, Esther Fala, Neil Gudsell, and Paora Maxwell.

Canterbury University re-joined the Council in 1987, but further financial difficulties in the early 1990s saw most constituent members withdraw from the Council. The Council was unable to survive and dissolved in 1992, ending an era in which music was an intrinsic part of campus life.

For more posters from the NZSAC collection, go to AudioCulture’s NZ Students Arts Council photo gallery.

--

These posters are copyright, and are held as part of the Tapuaka Heritage & Archive Collections, J C Beaglehole Reading Room, Victoria University of Wellington Library. They are published here with their permission. Thanks to Grant Robertson.