By 1977, after two massive No.1 New Zealand hits, and a high profile thanks to touring and television, Mark Williams had outgrown the local market. “I had to think about being a musician,” he said, 40 years later. To do that he had to come to Australia – “and learn.”

His first trip across the Tasman was in 1976 when Lew Pryme was his manager. In my 2017 interview with him, Williams recalled: “I lasted all of two weeks in Sydney and I went ‘I hate this place. If I ever come back here to live I won’t come to Sydney.’ So I came to Melbourne.” That was in September 1977. “I stayed here about a year just to acclimatise and it is the perfect city to acclimatise to Australia, then I could handle Sydney.”

The groups on the rise when he arrived included The Sports. Williams: “I went to see them and I couldn’t understand. Where was the feel? It was all wrong and I had to grow up. I had to start again. I really did. Right from Square One.”

While still the biggest star in New Zealand, Williams started again in Australia in 1978. It took him 10 years before he had a song in the charts.

Mark Williams, January 1986. - Chris Bourke

In 1986 Williams told Rip It Up he had no expectations of what would happen in Australia, “which was further solidified by the culture shock when I got here. I saw bands in Melbourne that were nothing like what I was doing – heavy, garagey, so different and so strong. I wanted to stay in pop and rock and roll, but this was different pop and rock and roll than I was brought up on!”

When he arrived, he was keen to work with feisty blues-soul singer Renee Geyer. “I wanted to learn off the greatest in my area.” The producer of his New Zealand hits, Alan Galbraith, who had recently left EMI in New Zealand, was also in Australia. “Alan moved over here and changed labels,” says Williams. “I changed with him, to CBS.”

Mark Williams's 1979 album for CBS, Life After Dark, produced by Alan Galbraith. - Photo by Greg Penniket, design by Richard Dunn

With Galbraith producing – and Mike Harvey writing most of the string arrangements – Williams recorded Life After Dark, which CBS released in 1979, after its first single (‘Wanna Give You My Love’) had been released a year earlier. Four of the tracks were self-written; other writers included Rod Temperton of Thriller fame (‘Groove Line’) and Billy Thorpe (‘Your Mamma Won’t Mind’). Neither Life After Dark or its singles made the Australian charts. “It was right at the end of the ‘blue-eyed soul’ period, before the takeover of punk,” Williams told Chris Bourke in a 1986 Rip It Up interview. “It made no impact whatsoever.

“I’m a calm person; if it doesn’t happen, I’ll leave it a while and try again. Financially it was hard because I had to start at the bottom, I was singing for a living, looking for a style. I couldn’t see myself as a punk! Once I got over the initial shock, I just grew with the times. I hated what I heard here, especially live, but living here I’ve adapted to it.”

Insert sleeve image from Mark Williams' 1979 CBS album Life After Dark, produced by Alan Galbraith. - Photography by Greg Penniket / Designed by Richard Dunn

A year after Life After Dark Williams started writing with Mark Punch, an in-demand Australian guitarist who played on the album (and also did sessions for Jenny Morris and Dave Dobbyn). “He wrote ‘Heading in the Right Direction’ for Renee,” says Williams. “And that’s how I got in with Renee and started working with her.” Mark Punch was also in Geyer’s band.

Williams’s first gigs with Geyer were in Melbourne; he did them for no fee. “It was like an internship,” he recalls. “I can sort of play guitar and keyboards and I ended up playing keyboards for Renee. We used to have good gigs.” Williams’s partner was in Sydney with a regular 9am-5pm job so for a short time she earned the money for the upkeep of the household.

Over the years Williams worked with Geyer, several other musicians moved through the band. Among them was South African drummer Ricky Fataar, who had had a stint in the Beach Boys (and played Stig in the Rutles, the satirical Beatles in the TV special All You Need is Cash). For much of the 1980s, Fataar was a Sydney-based producer, working with Geyer and Tim Finn.

With Punch, in the early 80s Williams formed Boy Rocking, releasing two singles that received little notice outside of dance clubs. “We also play live, which can be painful,” he said in 1986. “In a pub, there’s four or five or us, but it started with just two on stage. I used to play synth while Mark played a stand-up Simmons kit, or if he played the guitar I played the kit. It was a lot of fun, very free.” But the Australian industry, he said, was set up for bands so took little notice of Boy Rocking as a duo; by 1985 they were augmented live by the rhythm section of Australian Crawl.

“Every now and then we’d pull in Greg Sheehan who was a fantastic percussionist that we knew and Harry Brus [Australian Crawl] who we also knew who was a brilliant bassist – then we’d be a band. And we’d go mad.” But most of the time it was just Williams and Punch, alternating instruments. “We did that right through the 80s while I worked with Renee.”

His work with Renee led to many other sessions. “I’ve been on almost every album that’s been done in Australia,” he said in 1986. “recently I did an album for a Japanese pop singer Miki Agasuri, plus a soundtrack for a TV play … I’m a whore with my voice at the moment! Ads? Yes, heaps of ads!

“Renee got the shits. She said, ‘I can’t believe this! I find the perfect band and they all go off the next week to work for somebody else!’”

Williams also worked with Dave Dobbyn, singing BVs on the Loyal album in 1988. Among the other artists he provided backing vocals for in the 1980s were Jenny Morris, The Eurogliders, Ian Moss, The Church, Richard Clapton, Sharon O’Neill, Diesel, The Rockmelons, Marcia Hines and Margaret Urlich.

Williams is proud of his work as a session singer. “It’s a dirty word but that’s what I became,” he told me in 2017. The reason I went into session singing ... my old Torana that I bought in Melbourne ... It lasted me right until the early 80s. Every time it rained it would stop. It rained one day on the Harbour Bridge and ‘I went f--- art. I want money and I want a new car.’ That’s what I did. I rang up a friend of mine, a Kiwi and said ‘You got some sessions for me?’ and he said he’d give me a call.

“From then on I stopped being that guy who kept having arguments with Mark Punch and his brother about how this music should be – living it – dying it – how it should be creative. My whole life was falling apart around me.” He needed to earn some money and he did, being quick to learn new material and to record in the studio.

In 1988, Williams recorded ‘K.1.W.1.’ with expatriate New Zealander Malcolm McCallum, who wrote and produced the song, released on EMI. Again, its airplay was minimal.

Finally, in the late 80s, his luck started to change. Every night in 1989, lounges in Australia heard Williams’s voice – with Karen Boddington – on the original theme song for the Home and Away TV series. (The words and music were by Mike Perjanik who, like Williams, originated from the north of the North Island, as did Wahanui Wynyard who engineered the recording.)

Around 1989 Williams signed to Alberts, the family owned “home of the hits” publishing company, with the Easybeats’ ‘Friday On My Mind’ being one of their biggest. Williams recorded ‘Show No Mercy’ for Alberts, and it reached No.9 in the Australian and New Zealand charts.

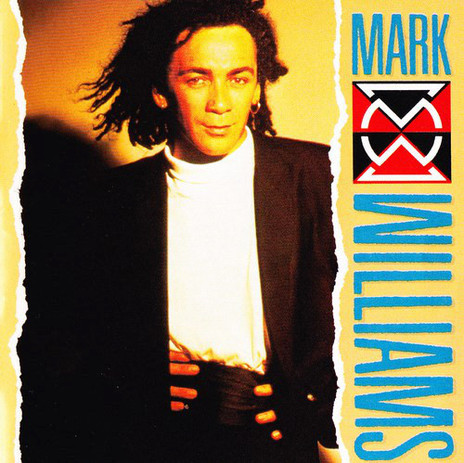

Mark Williams ZNZ, CBS/ Albert Productions, 1990.

An album followed in 1990 on Alberts, through CBS; called ZNZ, all the tracks – including ‘Show No Mercy’ – were written and produced by Harry Vanda and George Young (ex-Easybeats) who worked at Alberts for many years. Williams’s first New Zealand No.1, ‘Yesterday Is Just the Beginning of My Life’, had been written by Vanda and Young.

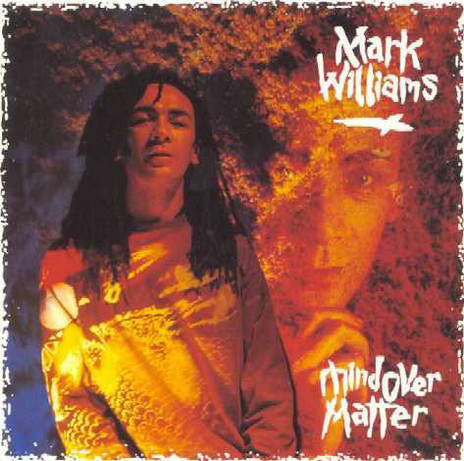

Mark Williams, Mind Over Matter, Albert Productions, 1992.

Williams recorded with Vanda and Young at the Alberts Studio in Neutral Bay from 1989 to 1993, and Alberts released another album, Mind Over Matter, in 1992. The company became involved in the production of the film Strictly Ballroom, which was a huge success in 1992, and Williams recorded ‘Time After Time’ with Tara Morice for the soundtrack. In all, he recorded and released five singles and two albums with Alberts.

While the success of ‘Show No Mercy’ lifted Williams profile on both sides of the Tasman, it was short-lived.

Mark Williams, Show No Mercy, Polydor, 1993.

This changed through very sad circumstances. In August 1997 Dragon’s Marc Hunter was diagnosed with malignant throat cancer and, after a short illness, died in July 1998. At the public memorial service held at St Andrews Cathedral in Sydney later that month, several artists performed Dragon songs. Invited by former Dragon keyboardist Alan Mansfield (Sharon O’Neill’s husband), Williams sang ‘Are You Old Enough’. It was a rendition which brought many mourners to tears, and Williams also found the experience very moving. “I could feel it. I could feel what was going on and that came right through in my voice.”

In rehearsal, Williams and the band had rehearsed the song, slowing the tempo right down. “I can’t believe how moving it was,” Williams told Troy Culpan in 2018, “and it was a really moving experience to actually sing it at that pace. It connected with everybody; it connected the whole story of Marc Hunter. It just seemed to connect and was just a fantastic experience. I don’t think Todd ever forgot that and eight years later when he thought it’s about time the songbook came out again I think that was the first thing he thought of and he gave me a call.”

Mark Williams and Bruce Reid from Dragon playing the Twin Peaks venue in Kaitaia, Northland, 2010 - Photo by Grant Stantiall

In 2006 Todd Hunter asked Williams to become the new front man with Dragon. Williams knew Marc Hunter, but not very closely. “I only saw Marc late at night at some dive after a gig,” he told Culpan in 2018. “Or I saw Todd just fleetingly but I never got to know them at all, so this was just a blast to get a call like that.”

He sees his role in Dragon as being that of a caretaker. “I had to stop where I was going because this is a commitment. What I’m there for is to continue the songbook. That’s what I’m there for.

“I’ve had to stop doing other things because of this band but that’s okay. It was a privilege to be asked to do something like that. I didn’t even know all the songs. I knew some of them but the whole songbook is just amazing.”

Dragon, 2018, from left: Todd Hunter, Mark Williams, Pete Drummond, Bruce Reid. - Publicity shot

At Dragon shows now, there is a heavy emphasis on audience participation. Williams guides the crowds to sing, sometimes giving them a line, or pointing to his eyes to remind the crowd to sing “snake eyes in paradise”.

There are times when the band stops playing and the crowd keep the music going. Often, a large percentage of the audience wasn’t even born when the songs were hits, yet they know all the words, especially for the big hits such as ‘April Sun In Cuba’ and ‘Rain’.”

The reincarnated Dragon released a single (and an album) called ‘Roses’ in 2014, and in 2018 Williams looked forward to their new 10-track album, Life is a Beautiful Mess. “We have no intention of stopping,” he said, “we just keep on working, recording, coming up with all these silly little ideas which are great because it actually keeps the spirit of the thing going … you’ll see us, just keep your eye on this page.”

Although Dragon seem to be touring constantly, in his downtime Williams writes songs, tutors young musicians in performance and singing – and still does his own gigs. One solo gig he did a couple of years wasn’t especially well organised: a band went on before him, whereas he thought he should have been the support act. “I’m still faced with challenges. I suppose I need that.”

Williams spoke about his expectation of crowds who go to shows where he performs. “I think we come from that old school. You’re giving people energy to feed back. I like it two-way. The only thing I don’t like seeing is people sitting and not moving. It’s a two-way street. You give and you get – I hope.”

Dragon, 2018, from left: Bruce Reid, Mark Williams, Todd Hunter, Pete Drummond. - Publicity shot

During our 2017 interview in Melbourne, Williams talked about looking after his voice. “I was concerned about my voice. Now, I know how to increase its longevity. But it took me 20 or 30 years – at least 25. I went through operations. But I came out and I can sing every night. That’s all I wanted to do.

“Nobody taught me. I had to learn how not to lose my voice. I had to teach myself about the art of singing because all through my career I have had terrible trouble with my voice. I had to learn what a singing teacher did.” Which is remarkable: when his contract with Alberts was terminated in 1993 he was told: “Let’s face it. You won’t have a voice in five years”.

Now, says Williams, “I teach singing from an organic point of view and I get huge success. I only work with about half a dozen students.”

So often in our 2017 conversation, the word courage cropped up: “It took a long time. If I’m doing stuff for myself the lack of courage comes back. But the moment I step on stage I’m all right.” Performing was easier with the band. “I love it. I’m so thankful. I’ve got three other people with me. It’s not just me. But in another way I really like that fear of going on stage. Sometimes I miss it. But it never leaves me when I go to do my own stuff. It comes right back again.”

Dragon, 2018, from left: Pete Drummond, Mark Williams, Todd Hunter, Bruce Reid. - Publicity shot

Williams reflected on the day he sang at Marc Hunter’s memorial, and the things that have happened since. “Is somebody going to give me a call?” he wondered then. “Well, they certainly did. I’m just thankful I’ve still got a voice and that I’ve learnt how to interpret through my life and how to be expressive and how to perform.”

In Sydney in 1986, while still waiting for his break to come in Australia, he said of his early success in New Zealand, “I look upon those years with pride. I’ve seen some of the stuff I did then – I don’t think I could do it again! So uninhibited. I loved it while I was doing it. I still am uninhibited, but with age you tend to get closed in.”

With ‘Show No Mercy’ in 1990, and all that has happened then – including new interest after the inclusion of 1977’s ‘A House for Sale’ on the Heed the Call funk compilation in 2017 – Williams showed getting “closed in” was yet to be an option.

--