Jim Pilcher has never played an instrument. “I’m probably tone deaf,” he says. “I just love music and I love what goes on behind the scenes.” In the 1960s Pilcher played a part behind the scenes in the careers of some of the country’s top musicians.

Jim grew up in the suburb of Taita, Lower Hutt, in a family of 10. Down the road was the Taita Community Hall, where the Hutt Valley Youth Club had been convening on Sunday afternoons since the mid-1950s. The sign outside read “No Jeans”. Not yet in his teens, Pilcher would stand tiptoe on an apple box outside the hall to peer in the windows, fascinated by the electrified sound of the rock’n’roll bands and the sight of hundreds of teenagers, dancing and mingling.

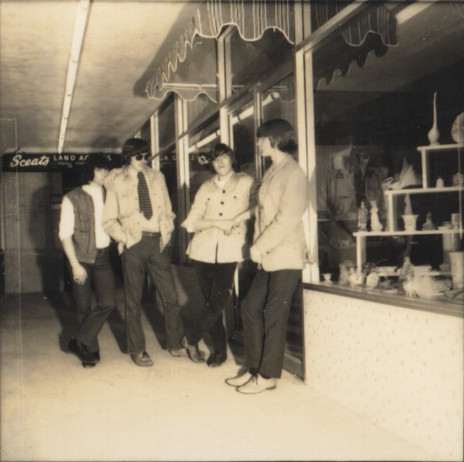

In the 1960s, the Hutt Valley Youth Club dances at the Taita Community Hall featured many of the top bands of the day. At this dance in November 1961 the acts included Tony and the Initials and the Premiers

On Saturdays he would volunteer to carry the equipment of projectionist Cyril Townsend and help set up the hall for the club’s weekly film screenings. “I just used to love to set up things. And I got a free view of the latest movies and the Saturday morning serials.”

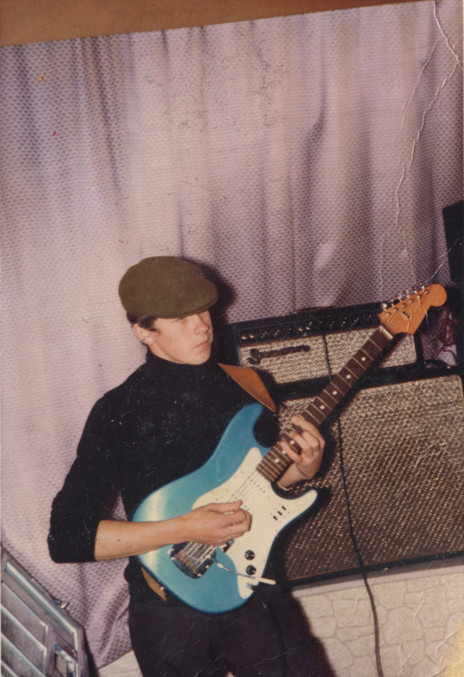

Once he was at Taita College he became a member of the Youth Club, and got to hear the bands up close. At first it was mainly Shadows-style instrumental combos like The Falcons with their star guitarist Blake Thompson, or The Imperial Twisters, whose drummer had lights inside his bass drum, which flashed whenever he kicked it.

Halfway through 1963 Jim turned 15 and left school, first to work at Hill’s Hats on Lambton Quay, then closer to home at the Griffin’s biscuit factory in Gracefield. His involvement in the Taita club continued to grow. He became an elected member of the committee. Soon he was in charge of booking the entertainment.

On account of his height and build, Jim was called on to act as bouncer at the club.

Around that time a new breed of band started to appear, inspired by The Beatles and the British beat boom. Jim would select bands from the rosters of the two Wellington-based agencies, Tom McDonald’s Universal Booking Agency and Ken Cooper Ltd. An afternoon dance would typically feature two groups: a well-known headliner, sometimes from out of town, and a lesser-known band to pad out the show. He recalls the main bands costing the club between £8 and £15 per performance. In those days Bari and the Breakaways – originally from Taranaki but now based in Wellington with an HMV recording contract – commanded the highest fees. At the lower end of the scale were groups like The In-Sect, a school band from Heretaunga College in Upper Hutt.

On account of his height and build, Jim was called on to act as bouncer at the club, though by his own admission he was no use if there was ever a fight. “Big as I was I was too gentle, never a scrapper.

“There was always rivalry though, between the Naenae boys and the Taita boys. It goes back to rugby days, on the field. And there was always an element in each area that could be pretty stroppy when things went wrong. There were a few knuckle-ups.

“But the Naenae copper, Hoppy Hodges, used to come over and give the Naenae boys a kick in the bum if they played up. The local Taita policeman was a guy called Jim Picknell and he would do the same, until they downsized local policing.”

Jim Pilcher at his 21st birthday, Avalon school hall, Lower Hutt, June 1969. From left are: Jim, Noel Koskella of the Roadrunners, friends Kerry Little and Paddy O'Gorman ( friend ) Midge Marsden (Bari and the Breakaways) friend Alan Strathern, Tim O'Connor (Roadrunners)

Occasionally the club would hold a jamboree with 10 bands. On these occasions they would use both the Lower Hutt Town Hall and the adjacent Horticultural Hall, with the crowds moving between the venues.

In 1966 Tom McDonald offered Jim a job with his Universal Booking Agency. “One of my jobs there was to look after the vans. Tom had a fleet of vans he used to hire out to the bands. There was always a quid in it for Tom somewhere along the way. He would hire out the band and charge the band to carry their gear around and I would drive them round.

“I’d driven The Gremlins, the Australian Pleazers, and I can’t remember if it was The Four Fours or The Dallas Four but they had guitars with gooseneck microphones coming off the neck – a great invention, they looked really good on stage [it was The Four Fours]. Through that link with Tom I got to know a lot of band guys because I was their driver.”

The Roadrunners, Taita, July 1966 (from left): Noel Koskela, Chaz Burke-Kennedy, Glyn Mason, Tim O'Connor

One band he got friendly with was The Roadrunners, a Hutt Valley teenage quartet with a fiery guitarist called Chaz Burke-Kennedy and a gritty soulful singer, Glyn Mason. Jim began doing their bookings and driving them to gigs as far north as Rotorua. The Roadrunners invited him to manage them. To bolster the band’s finances, he took a job at the Gear Meat Company freezing works in Petone. “I’d just started to grow my hair then. My first day on the floor there were these big Māori guys with their knives and sharpeners. ‘Come here Pākehā, we’ll cut your bloody hair!’ and I was terrified! So that lasted two weeks. Wasn’t me. I’m not a blood-and-gut man, though they did pay good money.”

The Roadrunners contemplate a midnight dip at Riddiford Baths, Lower Hutt, c1967. From left: Tim O'Connor, Noel Koskela, Chaz Burke-Kennedy, Glyn Mason

Jim’s earnings helped pay for the recording of three songs at HMV’s Wellington studios, under the supervision of engineer Frank Douglas. “But I wasn’t really a good manager. We didn’t have anyone here good enough to take a band overseas. We didn’t have any Brian Epsteins. I think if anyone had had the brains at that time, especially with the Roadrunners and probably even the Breakaways, to have a go at the UK market. At that time, when you had the Pretty Things and The Kinks and The Small Faces: I honestly believe the Roadrunners with Chaz’s guitar playing and Glyn’s voice would have been up there with them.” As it was, no records of the Roadrunners were released during their three-year existence, though two of the HMV recordings (‘Get Out My Life Woman’ and ‘L.S.D.’) eventually emerged on the 1992 garage rock compilations on Jayrem, Out From The Cold and Get The Picture.

Glyn Mason of the Roadrunners, at the Intermezzo coffee lounge, Wellington, January 1966

In 1966 McDonald sent Pilcher on a national tour with a package headlined by Waikato-born chart-topper Maria Dallas. She had just won the Loxene Golden Disc award with the country-pop earworm ‘Tumblin’ Down’. Also on the tour was the hit song’s author Jay Epae, as well as country singer Ken Lemon, Southland yodeller Max McCauley, south seas crooner George Tumahai, and the group Tony and the Initials.

Maria Dallas tour entourage, Christchurch, early 1967. From left, back row: Tony Eagleton (of the Initials), Don McMillan, Jim Pilcher; middle row: Terry Collier, John Naylor, Ken Lemon, Bruce Warwick; front: Leo Clarke, Maria Dallas, Max McCauley. - Jim Pilcher collection

“Bruce Warwick and I went down south and did the advance publicity. All the way to Invercargill putting up posters, checking out the venues. Tom being a bit of a tight-arse, we went in an Austin A40 station wagon, which Bruce and I had to sleep in for a couple of nights because he wouldn’t pay for accommodation, not even a motor camp.”

Ken Lemon (left), Jim Pilcher and singer-songwriter Jay Epae during the Maria Dallas Country Show tour in 1967. - Jim Pilcher collection

The tour opened in the Lower Hutt Town Hall. After a night in Levin “to iron out any bad points” they hit the South Island.

The Universal Booking Agency van gets a flat tyre near Picton, early in the Maria Dallas tour, 1967. Members of Tony and the Initials go into action. From left: Don McMillan, Terry Collier, Leo Clarke, Tony Eagleton (behind Leo)

“I was a driver, and setting up the stage and everything. We had bales of hay and we hired the Taita Youth Club’s PA system. We did hundreds of kilometres on that tour. Old picture theatres like Hokitika, town halls, community halls. Some halls weren’t that big but they were sold out. Everywhere we went was sold out and they got a great response. Balclutha, a great crowd there that night. The further down south you go, they’re really into their country music down there. They loved us in Gore.”

In Blenheim, the show was recorded by Ron Dalton of Viking Records for a live double album.

Jay Epae with Maria Dallas, at the Caltex Lounge, Taranaki Street, Wellington, in rehearsals for Dallas's national tour, February 1967

Jim also took a keen interest in bands visiting from overseas. When The Beatles and Rolling Stones toured, he was in line early for a ticket. As well as being a fan of the music, he was curious about the equipment they brought with them, which was bigger and louder than the locally made gear New Zealand bands had to make do with. In some cases, overseas bands would sell their gear here before leaving.

When The Who and Small Faces arrived in January 1968, Jim and a small group of friends were at Wellington airport to welcome them.

“We then found out they were staying at the Hotel Waterloo, so went down and were there when they arrived. We took photos out on the street of them hooning around. They went over to the wharves because they heard there was an English ship there and Keith Moon wanted to get some fish and chips. Security was pretty slack in those days. We’d gone up to their rooms and knocked on the door and they’d come out and greeted us.

Jim Pilcher with Keith Moon, Waterloo Quay, Wellington, January 1968

“I went to the Town Hall and went up to the stage and photographed all their gear before they played, Moon’s kit and all that. It was the first time I’d seen Marshall stacks. I recall they were purple and they belonged to the Small Faces. We asked, is the gear going back with them or are they selling it after their gig? Because Wellington was the last show. We asked one of the roadies, but he said no because it was under bond or something and had to leave the country. Not that we had the money to buy them anyway.”

Jim Pilcher with Paul Jones, Waterloo Quay, Wellington, January 1968. Jones, formerly of Manfred Mann, was touring as a solo act alongside The Who and The Small Faces

The In-Sect had been one of the younger bands Jim had booked at the Youth Club. By the end of 1967 they had left school, changed their name to The Fourmyula and turned professional. In 1968 their first single ‘Come With Me’, a gentle psychedelic pop song by the group’s in-house songwriting team of Wayne Mason and Ali Richardson, became the rare local original to make the national charts. The Fourmyula had also won the Battle Of The Sounds competition, with the prize of a passage to Britain, and left in early 1969, playing their way on the cruise liner Fairsky.

Jim was at the Lower Hutt Town Hall to witness The Fourmyula’s dramatic return.

Six months in Britain didn’t do much to advance their careers, though it did see them recording at Abbey Road, with the Beatles in the next room, and gave them an introduction to the new heavier rock sounds germinating in Britain. When they returned to New Zealand in late 1969 they brought with them a shiny set of Marshall amplification equipment.

Jim was at the Lower Hutt Town Hall to witness The Fourmyula’s dramatic return. “The curtains were drawn and we heard the beginnings of Led Zeppelin’s ‘Good Times Bad Times’. Then the curtains opened and there were these Marshall stacks, Marshall PA system, Hammond organ and a Leslie cabinet, and they just let rip.”

He recalls the crowd recoiling en masse, shocked by the unexpected volume of this changed band. At the end of the night as the hall emptied out, Jim offered to help the band pack up their gear. They were impressed when they saw him singlehandedly lift Wayne Mason’s Leslie speaker cabinet and carry it outside to their trailer. They promptly offered him a job as their roadie.

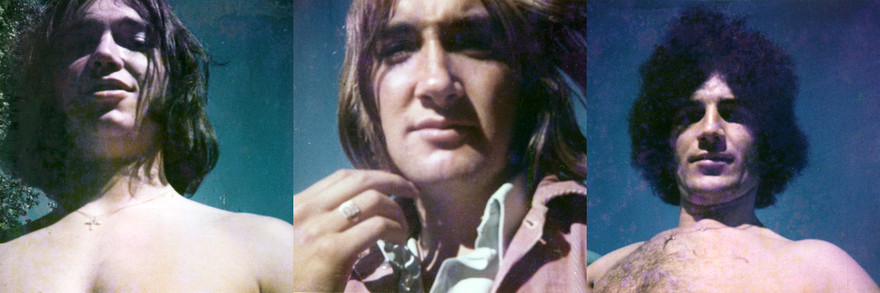

Ali Richardson, Carl Evensen, and Chris Parry of The Fourmyula, in Kaikoura, Spring 1969.

The Fourmyula were planning one more lap of New Zealand before heading back to Britain at the end of the year and Jim was invited to go with them. For their valedictory tour, the band paid Pilcher and themselves eighteen dollars a week each, the remainder going into savings for the trip.

Wayne Mason; Martin Hope (front) and Chris Parry of The Fourmyula, late 1969

The highlight of the tour was a Sunday night gig at Auckland club the Galaxie. “All the musos turned up. Not many Wellington bands made it up to Auckland in those days and I’ve got to admit they were pretty hot. Martin Hope was hitting his straps and Chris Parry’s drumming had improved immensely and I remember at the end of their set all the Auckland musicians stood up and clapped.”

Jim Pilcher's ticket to sail on the Fairsky with The Fourmyula from Wellington to Southampton, UK. The ticket is FOC - free of charge - but the band had to perform every day during the voyage.

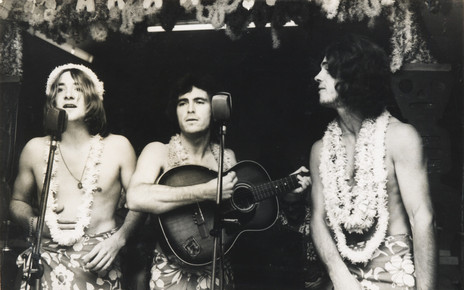

Fourmyula in fancy dress on the Fairsky: Carl Evensen, Martin Hope, Wayne Mason

After hours on the Fairsky, the Fourmyula mingle with other passengers. The band is, from left: Martin Hope, Carl Evensen, roadie Jim Pilcher, Ali Richardson, and Chris Parry. Wayne Mason is absent; the camera-shy man on the far right is unidentified

The Fourmyula’s second stint in Britain didn’t turn out any easier than the first. The band found a flat in Willesden Green, and signed a contract with Decca records. “We had a landlady with two kids who lived downstairs and we lived upstairs in two rooms, a lounge – four of them in one bedroom. I used to do all the cooking ‘cause I love cooking. When they were recording the album at Decca in West Hampstead I used to take them down lunch cause it wasn’t that far. When we were really on the bones of our bums we would live on a kilo or two of rice for two or three days. We were pretty frugal. Variations on mince.”

The Fourmyula outside their flat at Willesden Green, London NW10, late 1970

No sooner had The Fourmyula completed their album for Decca, the label had a purge and the group were dropped from its roster. The record would languish in the vaults for decades.

They continued to tour Europe for a while. “They were big in Scandinavia. They played at a club in Copenhagen called The Revolution and that was an eye-opener for a young guy from Taita. They had a secret club at the back of the stage called the Key Club – the members had to have a key to get into it – and we could go there and there were all sorts of things going on. The Danes are pretty naughty at times.” Back in New Zealand, the youth clubs and other venues Jim had worked in hadn’t even been licensed to sell alcohol.

Shane and The Fourmyula at their London flat, 18 Mount Pleasant Road, Willesden Green NW10, February 1971. From left: Shane, Carl Evensen, Martin Hope, and Bruce ‘Phantom’ Robinson (former member of the Pleazers with Shane, and at this stage his musical director)

Still the band struggled. Jim worked a series of factory jobs to help pay their London rent. Then he received a letter from the Home Office informing him that his visa had run out. With 12 days to leave the country he had to borrow money for his fare home. He returned to New Zealand in July 1971, and to the Griffin’s factory where he would work for the next two decades.

Reflecting on The Fourmyula’s experience in Britain, he says: “If they had been as big (in New Zealand) in ’65 as they were in ’69 and gone to England at that time with their bubblegum poppy type stuff, they could have been right up there. But the bubble had burst. They arrived at the end when the music scene was changing and they hadn’t quite changed with it yet.”

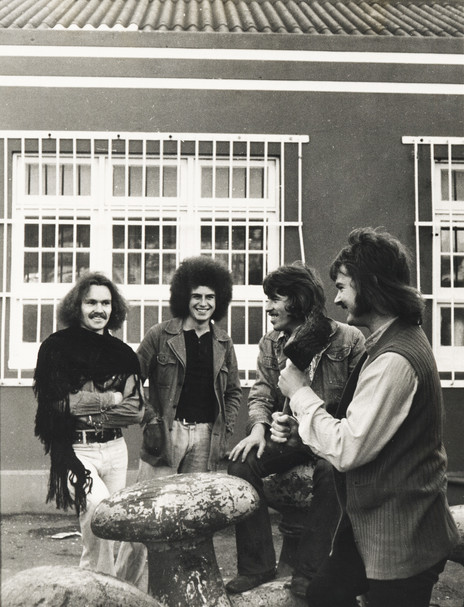

Wellington band Gumboot, mid-1970s. From left: Chaz Burke-Kennedy, Stewart Fraser, Tim O'Connor, Noel Koskela - Jim Pilcher

Jim’s interest in music didn’t die. In 1973, Rockinghorse formed in Wellington from the remnants of the Fourmyula. For a while Jim drove their van. A couple of years later he performed a similar role for Gumboot, a short-lived outfit which included ex-Roadrunner Chaz Burke-Kennedy. But by this time Jim was married with two children, working full-time to support them. Music would be for the stereo and the scrapbook.

---

More images from Jim Pilcher's collection

The Roadrunners contemplate a midnight dip at the Riddiford Baths, Lower Hutt, c1967. From left: Glyn Mason, Noel Koskela, Chaz Burke-Kennedy, Tim O'Connor

The Roadrunners shopping for some threads on Lower Hutt's High Street, c1967. From left: Chaz Burke-Kennedy, Glyn Mason, Tim O'Connor, Noel Koskela

Chaz Burke-Kennedy, Noel Koskela and Tim O'Connor of the Roadrunners, at the Intermezzo coffee lounge, Wellington, January 1966.

The Roadrunners, Taita, July 1966 (L-R): Noel Koskela, Chaz Burke-Kennedy, Tim O'Connor, Glyn Mason

Tony And The Initials just after arriving in Picton from Wellington at the beginning of The Maria Dallas Tour, February 1967. At the far left is roadie/driver Jim Pilcher - Jim Pilcher collection

The Universal Booking Agency van in the back streets of Queenstown, 1967

Bubbles for the Fourmyula on board the Fairsky, December 1969-January 1970. From left, Ali Richardson, Martin Hope, Chris Parry, roadie Jim Pilcher, Carl Evensen, Wayne Mason

The Kal-Q-Lated Risk, from left: William Davidson, Robert Coulter, Phil Hope, unidentified, Bernard Carey - Jim Pilcher

Wellington band Gumboot, on the ramp of the Taranaki Street wharf, mid-1970s. From left: Tim O'Connor, Chaz Burke-Kennedy, Noel Koskella (back), Stewart Fraser (front) - Jim Pilcher