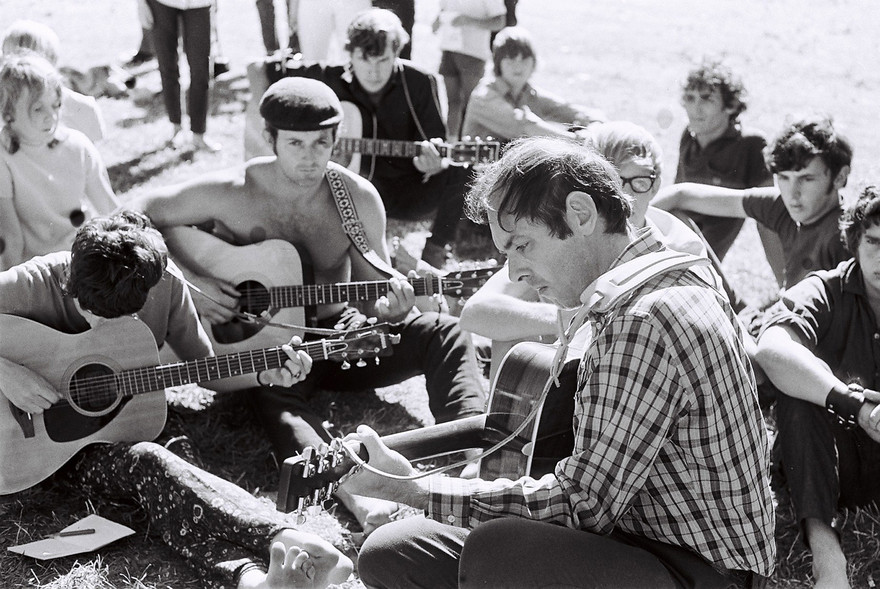

A jam at the 1968 National Banjo Pickers' Convention featuring at right, Mac Odell on banjo and mandolinist Graham Lovejoy - Trevor Ruffell

The National Banjo Pickers’ Conventions were about a lot more than the instrument that gave the event its name. In a 1968 Listener feature, Auckland blues aficionado Alan Young wrote that the range of instruments features “would amaze those who somewhat uncharitably equate folk music with a rather battered guitar – played badly at that.”

Besides banjos and guitars, among the instruments on display were mandolins, violins (“fiddles in country music parlance”) autoharps, two proper double-basses and a large number of tea chest basses, a dulcimer or two, mouth harps … “and a truly amazing selection of kazoos”. Workshops were held in these instruments – except the harmonica and kazoo – and at the 1969 convention visiting US musician Mike Seeger displayed his skills playing almost all of them. (Seeger was half-brother to banjo proselytiser Pete, who donated $100 to the event.)

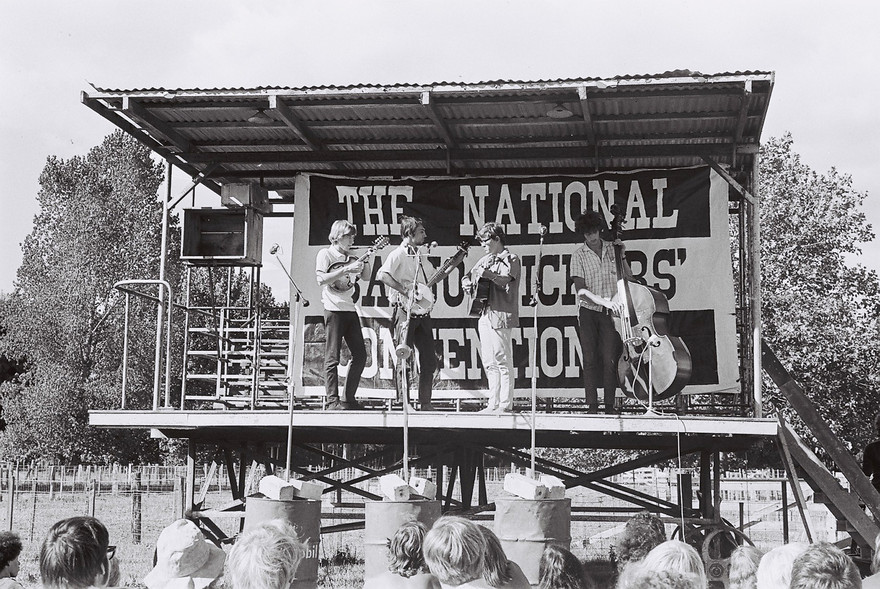

Outdoor stage, 1970 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention. - Trevor Ruffell collection

Michael Grace, who conceived the idea for the convention, says his interest in the banjo predated The Beverly Hillbillies hit and came from a different line than George Formby’s novelty songs. The folk movement of the 1950s celebrated a long line of music making by the people that began in the 1700s with the Irish and Scottish immigrants to the US. In the wake of The Weavers’ success in the 1950s – followed by The Kingston Trio with its "simplistic" technique – folk clubs were thriving around the world.

New Zealand was no different: folk clubs were thriving. Folk music and the peace movement were bedfellows, and regarded as left wing enough that, says Grace, the Customs Department could take an interest in the importation of a Pete Seeger banjo manual.

What Grace envisaged in 1967 as a small gathering for New Zealand banjo enthusiasts quickly evolved into folk festivals that celebrated folk, country, bluegrass, jug bands and traditional ballads. Despite the popularity of folk and the banjo, reflected Grace in 2018, “Some things in history were always going to happen. This was not like that. If I hadn’t decided to do this in rush of blood it would never have happened. The conventions were formed on back porch of Paul Trenwith’s parents’ house in Te Rapa.”

While The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band was already nationally famous, and a star was the old time banjoist Jim Higgott, who had been performing in Auckland since the 1920s, it was the grassroots music-making that many attendees took away as their most memorable moments. At the tent-town Scruggsville – temporary home to 500 people under canvas – Young said it was not “considered impolite to just wander into a tent if you liked the music emanating from within, but once inside you were expected to join in with whatever instrument you had with you.

David and Panda (Dave Calder and his wife Andrea), 1968 National Banjo Pickers Convention - Trevor Ruffell

“Normal sleeping hours also went by the board: one of the many impromptu and short-lived bands that sprung up in the town was formed at 3am on Sunday morning at the end of Fingerpicker Lane, one of Scruggsville’s main streets. The group played for an hour to an appreciative audience and then disbanded, because the members were too cold to play any more.”

At the 1968 convention the erratic weather meant that musicians carried their instruments with them at all times, as one rainstorm moved off “only to make room for the next one a few minutes later”. After a dinner of sausages, peas and potatoes, the first concert began on Good Friday at 7pm and didn’t finish until seven hours later. Those who lasted the distance heard samples of just about every facet of folk music from wailing blues through country music to the beautiful close harmonies of unaccompanied English ballads.

A jug band at the 1970 National Banjo Pickers' Convention, Claudelands showgrounds. - Trevor Ruffell

Paul Chisolm wrote of the 1970 convention, “The meandering of barefeet and sandals from tents of country music to tens of contemporary sounds, or just tents. Clusters of cross-legged participants, percussionists, harmonist, or “just listenings” focusing upon the spontaneous groups playing that nebulous sound: folk music. The sun glinted all day from camera lens, the polished wooden bodies of guitars, and white teeth as unexpected harmonies or moods of the music appeared.”

Young musicians at the 1970 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention. - Trevor Ruffell

The Old Time Square Dances were especially popular at the conventions even though, Young estimated, 475 of the 500 dancers did not know what a square dance looked like before twirling on the dance floor under the guidance of caller Thelma Blyth. (Square dancing had been so popular in the 1950s that the Education Department organised sessions in primary schools throughout the country. And in fact banjo playing had boomed in New Zealand during the 1910-1930s, under the tutelage of mentors such as Louis Bloy and Walter Smith)

Behind the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, the sound technicians of the 1970 National Banjo Pickers' Convention; in the background, square dancing. - Trevor Ruffell

In 1968, alongside the purists earnestly replicating the sounds of rural Kentucky and Appalachia – and performing material by The Carter Family, Bill Monroe, plus children’s songs – were outfits such as The Mad Dog Jug Jook and Washboard Band performing ‘High and Dry’, and the George Wilder Rehabilitation Society Bush Band playing not novelties but traditional New Zealand songs such as ‘I’m Packing Up My Things To Go Home’. By 1970 the repertoire also included the Beatles’ ‘Rocky Raccoon’, performed by Steve Robinson, whose group “The Tamberlain” also performed contemporary folk pop such as ‘There’s Something Wrong’ (James Taylor) and ‘The Only Living Boy in New York’ (Paul Simon). Marion Arts, later of the Red Hot Peppers, sang Dylan’s ‘It Ain’t Me Babe’ backed by the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, and Stoney Lonesome closed the final concert with Creedence Clearwater Revival’s ‘Proud Mary’.

After four conventions, the event was a victim of its own success, suggested founder and organiser Michael Grace, who announced there would be no more in the February 1971 issue of folk magazine Heritage. The aims that Grace, with Paul Trenwith and Alan Rhodes, had sketched out “one summer evening in late 1966” had been “achieved and surpassed”.

Square dancing at the 1970 National Banjo Pickers Convention. - Trevor Ruffell

Part of the problem was that the success of the first convention in 1967 – which cost $200 to organise – led to the inclusion of guest artists from overseas. This increased costs and ticket prices: the convention of 1969 cost over $4000 to put on. After limiting registrations to the 1970 convention – which Grace believed was the most successful of them all – the event lost money and had to tap into its reserves from earlier years’ profits.

A 1971 convention would need to be even larger – and perhaps still lose money – or not to include an overseas act, which would mean it would have “duplicated the work that the smaller festivals are doing very effectively.”

Marion Arts, later of the Red Hot Peppers, picking a quiet spot during the 1970 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention. Among other songs, she would perform Dylan’s ‘It Ain’t Me Babe’ that year, backed by the HCBB. - Trevor Ruffell

Also, wrote Grace, “I believe that there are no longer the numbers of young people coming into ‘grassroots’ country music that there were in the mid-sixties, and we would have to try to appeal to an ever increasing range of tastes, thus defeating one of our main aims.”

While announcing the decision with regret, Grace said, “we have done all that we set out to do, and all that would be left would be to radically change our aims and continue, purely for continuation’s sake.”

In 2018, Grace said that for participants of a certain age group, the conventions were “an eye opener ... they were becoming independent, and able to sing own music that wasn’t their parents’. Many people have come up to me since and said those conventions were one of great experience in their lives, in their development as individuals. To be told that decades later is quite a thrill.”

The legacy of the festival can be seen in the many recordings that New Zealand acts made after appearing on the Te Rapa stages, including the three LPs of highlights that Kiwi released of the 1968, 1969, and 1970 conventions. The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band became national heroes – helped by one-channel television and Country Touch. Jim Higgott enjoyed a late-career burst at Auckland’s Poles Apart folk club. Max Winnie displayed his prowess at blues and folk at Wellington’s Monde Marie. Tamburlaine and Stoney Lonesome made accomplished albums. Who knows what became of the children who took to the outdoor stage to show their finger pickin’ skills?

--

From left, Paul Trenwith and Dave Calder of the HCBB jam with US guest Bill Clifton at the 1970 National Banjo Pickers Convention. - Trevor Ruffell

An all-star finale at the 1970 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention. - Trevor Ruffell

Bil Clifton from the United States, the overseas guest at the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention, 1970. - Trevor Ruffell

Bill Clifton holds an impromptu workshop - 1970 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention. - Trevor Ruffell

An unidentified banjo player joins The Mountain Ramblers for some spontaneous music making at the 1970 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention. From left: Christine Cummings, Harvey Whincop, Ian Turbitt, unidentified. - Trevor Ruffell

A flyer for the 1968 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention.

Alan Rhodes and Colleen Bain of the HCBB in the camping grounds at the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention, Hamilton, 1970 - Alan Rhodes collection

Alan Rhodes and Colleen Bain of the HCBB in the camping grounds at the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention, Hamilton, 1970 - Alan Rhodes collection

--

Read more: The National Banjo Pickers' Conventions, 1967-1970

Read more: Duelling Banjos – a photo album from the National Banjo Pickers' Conventions.