Less than a year later, with a self-titled LP that left them with mixed feelings, Stoney Lonesome split in two. Three of them kept the name for a time, intending to fulfil a second album that never came to fruition.

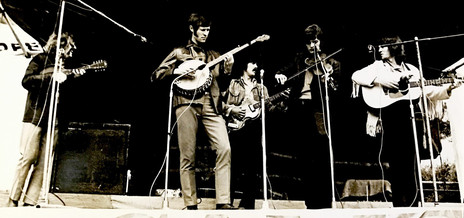

Formed as The Stoney Lonesome Boys in the late 1960s, they were an exciting live act around Canterbury and released an EP on local label Cindy. They shortened their name and made appearances around New Zealand and on the NZBC television shows The Country Touch and Movin’.

Stoney Lonesome left audiences breathless wherever they played.

The 1970 album Stoney Lonesome caught them in transition from a straight-ahead bluegrass sound to contemporary covers of The Rolling Stones, Creedence Clearwater Revival and The Lovin’ Spoonful, something that didn’t sit well with some of them. But for the 18 months or so leading up to the album, Stoney Lonesome left audiences breathless wherever they played.

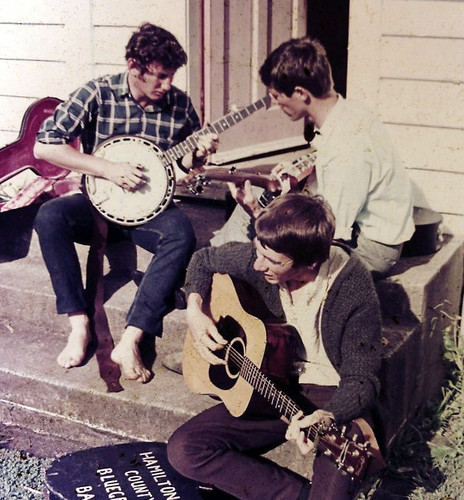

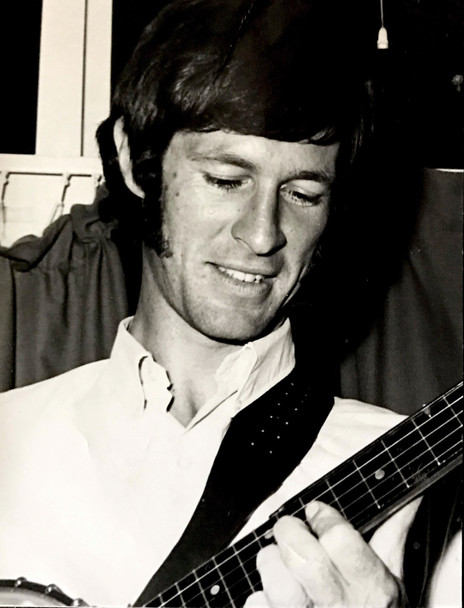

The moment Christchurch schoolboy Clive Collins heard The Kingston Trio’s banjo-led ‘Tom Dooley’ in the late 1950s, he knew he was destined to play the instrument. He discovered the banjo played by Dave Guard in the song was a five-string, but wasn’t deterred when the local music shop stocked only four-stringed ones. Soon finding out the fifth string was what gave the instrument its unique sound, he upgraded to a five-string from Begg’s Music Store.

His thirst for the banjo led him towards Earl Scruggs and bluegrass music and during the 1960s he imported books and records to improve his playing. He even devised a way to slow down his record-player turntable by moving the driver belt to the shaft so he could hear precisely what was going on.

Collins and friends played in various string bands and when the guitarist in his old-timey Instantaneous String Band departed, he drafted fellow Folk Centre regular Jim Doak in as a replacement. But the band didn’t last and by early 1968 it was just Collins and Doak.

No more than three weeks out from the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention in Hamilton that Easter weekend, Collins hastily taught Doak nearly 30 bluegrass banjo tunes for the event. The material was all new and mysterious to the singing guitarist, who initially struggled to modify his old-timey guitar runs to the simpler bluegrass accompaniment. The pair’s ‘Franklin County Special’ can be heard on the Highlights From The 1968 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention LP released on Kiwi.

During that year they brought in Ivan Wilson on upright bass and tenor vocals and formed The Beale Street String Stretchers. They performed at folk concerts around the city, backed singer Christine Smith on ‘Tramp On The Street’ (the b-side of her Master single ‘Leaving On A Jet Plane’), and ventured to Auckland for a spot on television show The Country Touch.

On the day of filming, Len Cohen from The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band egged Doak on to sing “shark-infested custard” instead of “shark-infested water” in their number ‘Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight’, but “don’t do it in rehearsals, do it when we go live”. It got a laugh from the cameramen and the Country Touch Singers, but Doak incurred the wrath of the usually mild-mannered producer Bryan Easte and the cast had to redo the entire second half of the show.

At the end of the year, The Beale Street String Benders disbanded and Collins and Doak reverted to a duo using the moniker Amelia’s Custard Crooners as a nod to the Country Touch episode. They added upright bass player and tenor singer Miles Reay and became The Stoney Lonesome Boys – so named after Bill Monroe’s bluegrass instrumental ‘Stoney Lonesome’. The ‘Boys’ was added in recognition of the likes of New York’s The Greenbriar Boys and many other bluegrass groups of the time that employed the description.

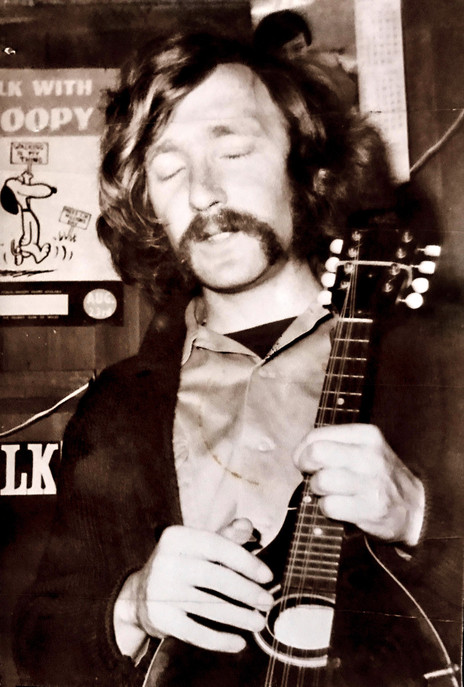

Reay had played in rock bands around Christchurch but had recorded programmes of folk music for Radio 3YZ in his home town of Greymouth, as a soloist and with The Greenstone Four. When former Instantaneous String Band member Brian Egan returned to the city from Australia he joined The Stoney Lonesome Boys on mandolin.

Throughout 1969 the quartet appeared at the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention – featuring with ‘Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight’ including the infamous “shark-infested custard” line on the highlights LP – and the annual University of Canterbury Folk Music Club concert as well as guest spots at various folk shows.

The next year they were at the Wellington Folk Festival and entered a Radio 3ZB competition that called for contestants to perform a song from a film or TV show. Their ‘The Ballad Of Jed Clampett’ from The Beverly Hillbillies didn’t bring them victory but was impressive enough to garner The Stoney Lonesome Boys further promotional work for 3ZB. They also reached the semi-finals of the 1970 Mobil Song Quest with the gospel cover ‘Wicked Path Of Sin’.

Small Christchurch label Cindy Records enlisted the band to record a song for a compilation EP that led to them then laying down eight tracks for their own EP called Country And Western Great Eight, which Cindy sold in supermarkets. Among the tracks were Johnny Cash’s ‘A Boy Named Sue’ and ‘Ring Of Fire’, and The Beatles’ ‘I’ve Just Seen A Face’. When it transpired the band members were expected to buy their own copies, Jim Doak for one refused to.

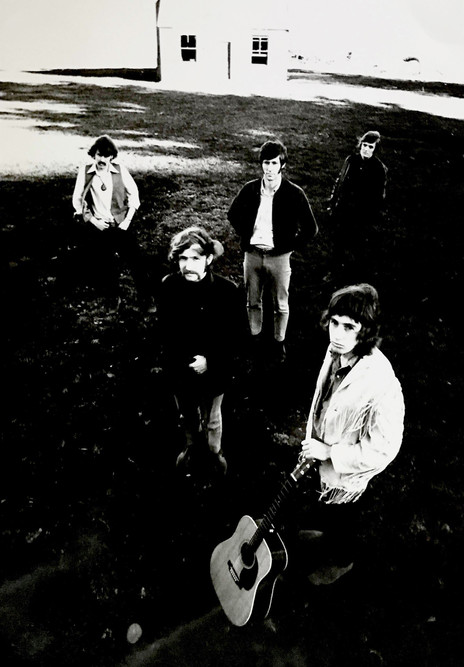

The band shortened its name to Stoney Lonesome and became a quintet.

The Stoney Lonesome Boys added to their number with jovial Christchurch Folk Club singer and MC Tony Brittenden, a big personality who had appeared on the children’s TV show Ah De Doo Dah Day and its accompanying LP. They coerced him into joining on Dobro, but before he could purchase the instrument Miles Reay left and Brittenden moved to electric bass. After just a few months, Reay replaced the departing Lyndsay Bedogni in The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band on the cusp of its relocation to Sydney.

The band shortened its name to Stoney Lonesome and became a quintet. Former Timaru Jug Band multi-instrumentalist Richard Oddie was a fan of the band and every time he crossed paths with Jim Doak he asked to join. They didn’t need a classical guitarist or mandolinist or picker of any other instrument Oddie extracted from the wall at Hutchinson White and played proficiently, so they told him when he could play ‘Orange Blossom Special’ on the fiddle he could come on board.

A short time later, on the eve of the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention, Stoney Lonesome members were unloading from the back of their car in Timaru when Oddie showed up with a fiddle and performed ‘Orange Blossom Special’ right there on the footpath. “Alright, you’re in.”

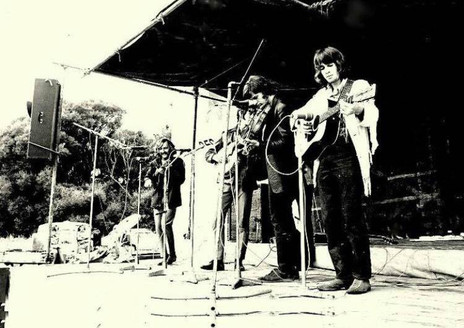

Until 1970, the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention had been a mostly acoustic affair, but that year Tamburlaine brought in an electric bass and the new-look Stoney Lonesome appeared with Tony Brittenden and his Paul McCartney Beatles bass. As their performance of ‘Freeborn Man’ on the film of the event Keep On The Sunny Side and their ‘[Bringin’ In The] Georgia Mail’ and ‘Proud Mary’ on the 1970 highlights LP proved, Stoney Lonesome were on top of their game.

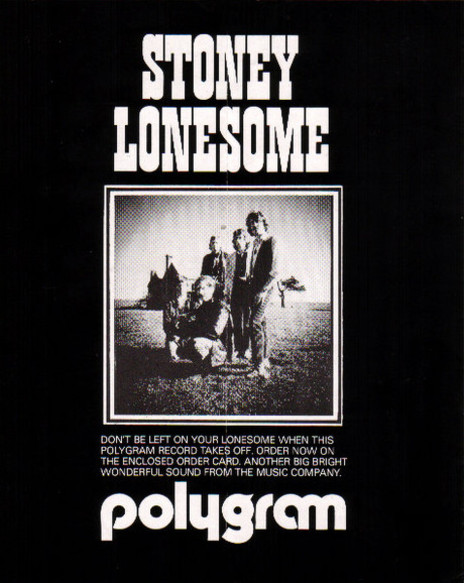

A number of record labels were now interested in an album. At the forefront were HMV producer Peter Dawkins and newly independent producer Barry Coburn, who had not long resigned from Viking Records. Stoney Lonesome had counsel that Dawkins’ interest might be purely a bid to tie Stoney Lonesome up so as not to impede on HMV’s other bluegrass outfit The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band’s recent success. Dawkins argued he saw Stoney Lonesome more in the vein of The Band, whose first two albums of roots music had set a new benchmark for musicians in all genres.

All the same, Stoney Lonesome were wary of a possible conflict and opted for Coburn who set up a deal with the newly named PolyGram Records NZ to have the LP released on the Polydor label. He flew them up to Auckland to start work at Mascot Recording Studio, but it wasn’t an entirely easy experience: the sterile studio environment was at odds with the band’s expectations.

They picked numbers from their live repertoire. Those that worked best were Greenbriar Boys covers ‘High Muddy Waters’ and ‘Roll On, John’ where they sat around and played live. The songs that required separate overdubs didn’t fare so well in the energy stakes. Coburn brought in a session drummer for the contemporary material ‘Everybody’s Talkin’’ and the spur-of-the-moment Rolling Stones cover ‘Country Honk’ – complete with party atmosphere and Tony Brittenden’s muffed chorus lyrics.

One of the highlights of the stay in Auckland for Richard Oddie was jamming on acoustic guitar at a party with pop star Shane and his musical director and former Pleazers bandmate Bruce “Phantom” Robinson. The irony was when the band received the completed Stoney Lonesome album they found Coburn had added Robinson on bottleneck guitar as well as overdubbing strings on some tracks. It didn’t go down well.

The single ‘Never Goin’ Back’ (featuring Robinson) b/w ‘Rocky Top’ preceded the album late in the year and for several months held the No.1 spot on the local charts, as determined by a weekly public vote. What the radio station didn’t know was that bassist Brittenden, a high school art teacher, was having his pupils fill out voting forms before admitting them to class. When the station withdrew the official voting forms, he had his expert typist mother prepare a perfect copy that he ran off.

Brittenden was also responsible for the Stoney Lonesome LP cover, which he designed and drew out on art room card, cut out with a craft knife and pasted onto a white backing board. The embossed Beatles “White Album” effect he was after was somewhat lost when a PolyGram art director decided it would look better with a grey tint.

The band opened for Jerry Lee Lewis in Christchurch, and on a live tv show performed ‘Bringin’ In The Georgia Mail’ from a cardboard train.

When they weren’t out of town, the band held a residency at The Shoreline nightclub in New Brighton, they opened for Jerry Lee Lewis at the Theatre Royal in Christchurch during the rocker’s country music revival, and television producer Bryan Easte showed all had been forgiven regarding Jim Doak’s “shark-infested custard” when Stoney Lonesome were guest artists on The Country Touch.

During an appearance on live pop TV show Movin’, filmed in Christchurch, they were to perform Flatt & Scruggs’ ‘Bringin’ In The Georgia Mail’ from a cardboard train. As the stage crew moved the set between songs one of them stood on Tony Brittenden’s bass lead, breaking the jack plug. As the floor manager counted down, a guitar lead came flying from in the direction of resident band Chapta and Brittenden just managed to plug it in for the band to start on cue.

Evident on the album, the band members were pulling in different directions. By the time they took a break to prepare for a follow-up LP, Doak and Brittenden had discovered Fairport Convention’s Unhalfbricking and Brittenden’s fledgling writing was more in that vogue. The material was going further away from the bluegrass style that Clive Collins loved and had founded the band on.

The inevitable fracture came in April 1971. Brittenden told The Star newspaper, “There was no ill feeling – the split was quite amicable.” He said he, Doak and Richard Oddie would continue as Stoney Lonesome in a “semi-electric folk” direction and he was still negotiating with PolyGram to release an album that the original line-up were to have recorded the following month. The report said Collins and Brian Egan were undecided on their future.

Of course the second album never eventuated. In fact, the band would probably admit that the first happened before they were really ready for it. Later, Brittenden and Doak joined forces with Alistair Hulett in Waite while Collins and Egan continued in groups such as Rural Delivery. At times Oddie joined both line-ups, but none reached the heights Stoney Lonesome had in 1970.