How many banjo pickers does it take to stage a music festival? In Te Rapa in 1967, organiser – and self-proclaimed “benevolent dictator” – Michael Grace is in the centre of the doorway, Paul Trenwith (Hamilton County Bluegrass Band) is second from him on the left, Clive Collins is to the left of Trenwith. Third from right tuning his banjo is John Ruffell, who recorded the conventions and later co-owned Kiwi Pacific Records. Behind him, with head turned left, is Chris Thompson. Sitting in front are Frank Sillay (head turned), Sandy McMillin and Alan Rhodes (both HCBB). Steve Robinson (Tamburlaine) is in the centre wearing a white shirt with Giles Baskett in the sunglasses to his right. Photo credit: Tony Ward (David Calder collection)

--

At first the notion of a national banjo festival taking off in New Zealand seems as unlikely as a family of hillbillies striking oil and taking up residence in Beverly Hills. But it makes more sense when viewed in its time: the festivals occurred in the wake of folk boom in the early 1960s when a bunch of young musicians were turned on to the instrument. Some of the New Zealand enthusiasts emerged from the folk clubs early in the decade; others came via the theme music of an American TV comedy.

Apart from the folkies, all that most people knew of the banjo in this part of the world was as the instrument of choice for dixieland jazz, or regrettable blackface minstrel shows. The US folk boom and interest in “old timey” music generated new enthusiasts for the five-string banjo (as opposed to the four-string instrument of dixieland jazz). The five-string banjo’s popularity increased with The Kingston Trio’s ‘Tom Dooley’ and was broken wide open by Earl Scruggs’s bluegrass banjo playing on ‘The Ballad Of Jed Clampett’ – the theme of The Beverly Hillbillies.

The sound influenced a bunch of aspiring musicians around the country – three of whose paths would converge in Christchurch and Auckland and ultimately bring about New Zealand’s first multi-day national music festival. The common denominator was the tall, blond-headed Michael Grace, who had met banjo enthusiast Clive Collins down south before moving to Auckland and meeting aspiring banjo picker Paul Trenwith.

The tents disappeared into the distance, and from many of them music emerged from spontaneous combos and jug bands. “It was rowdy but fun,” recalls organiser Michael Grace. “That tea-chest bass is a very sophisticated version. It’s even got a finger board.” Photo credit: Trevor Ruffell (Michael Grace collection)

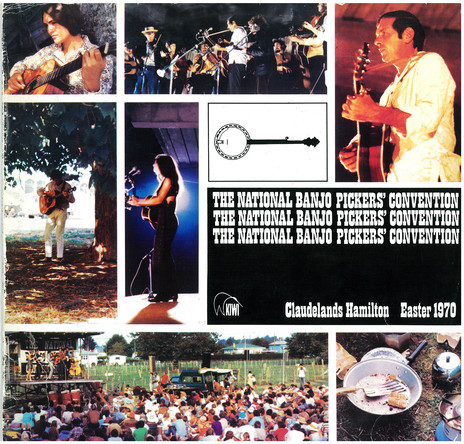

The National Banjo Pickers’ Conventions preceded Redwood 70 by three years and the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival by six. The first one in 1967 drew fewer than 200 people to Te Rapa, on the outskirts of Hamilton, but by the time of the final one in the Hamilton suburb of Claudelands in 1970, that number was more than 3000.

The first two featured solely New Zealand talent, but the final two included American guest artists Mike Seeger in 1969, and Bill Clifton in 1970. Both visitors mingled with the festivalgoers and ran workshops. Clifton even hung around to record an LP with the country’s foremost bluegrass outfit The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band.

The original Hamilton County Bluegrass Band line-up at the inaugural National Banjo Pickers’ Convention, 1967. Left to right: Colleen Bain, Dave Calder, Len Cohen, Paul Trenwith, Alan Rhodes, Sandy McMillin. Photo credit: Tony Ward (Michael Grace collection)

The conventions were the brainchild of ex-Christchurch music fan and banjo picker Michael Grace. His concept was to bring together like-minded folkies to share ideas and play music. Newspaper clippings of the time mentioned the conventions included concerts, square dances, workshop sessions for folk singers and instrumentalists and discussion groups.

By the time of the Second National Banjo Pickers’ Convention in 1968, soundman and low-energy nuclear physicist John Ruffell and his cohort Robin Gummer, a classical music fan and electronics whiz, were not only mixing the live sound but were recording the entire proceedings and had convinced Kiwi Records to release the highlights on an LP.

The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band were already established recording artists, but for acts such as Marion Arts, Tamburlaine and Stoney Lonesome, the highlights albums were a step on the way to releasing their own records. For others such as The (Regurgitated) George Wilder Rehabilitation Society Bush Band, The Mountain Ramblers and The Buckhead Strugglers, it was their sole appearance on vinyl.

Mandolin player Dave Calder is a picture of concentration performing with the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band. Photo credit: Trevor Ruffell (Michael Grace collection)

The success of the inaugural convention left no doubt the event would continue. Grace advertised informally through the folk music clubs and universities, and musicians just showed up. “I didn’t need to book anybody,” he told AudioCulture. “It just all happened.”

“I obviously knew a bit about them in advance because there’s the New Zealand network, so very few people turned up who were total, total strangers. But we were singing and playing music pretty much three or four nights on end, so I got to know pretty well the calibre of every individual and group.”

Having witnessed the talent at close quarters, when it came time for the final concert each year, Grace could assemble a top-notch programme out of those who had impressed him most over the days leading up.

A flyer advertising the 1968 National Banjo Pickers Convention at Te Rapa, Hamilton. The publicity material was all hand-lettered by Michael Grace, the graphic design was by Carole Shepheard, later a prominent artist. - Michael Grace collection

To hear Hamilton County Bluegrass Band banjoist Paul Trenwith explain it, the convention was a folk festival with an emphasis on banjo playing. “And that was what it was always intended to be,” he added.

By the time of the second convention in 1968, the programme stated: “The National Banjo Pickers’ Convention is a BANJO pickers’ convention in name only, though there are many banjo pickers present. In reality it is an annual meeting of folk singers, musicians and enthusiasts from all over NZ whose interests range from traditional to contemporary, and a few other categories as well. However, the convention leans, traditionally, towards country and mountain music.”

It was not a commercial endeavour. Each convention broke even with just enough left over to set up the following year’s event. After paying the bills for the final one in 1970, Grace spent what was left on a big dinner for 20 or so organisers in an upmarket Auckland restaurant. The festival had grown beyond his wildest dreams and he had no inclination to continue.

Mac Odell from the Palmerston North Bluegrass Band displays his skills on a five-string Gibson banjo; note the tuning peg halfway down the neck. Graham Lovejoy is on mandolin. Photo credit: Trevor Ruffell (Michael Grace collection)

“The last one was, as is often the way, the biggest and the best,” he remembered. “But at that stage the whole sort of Woodstock thing was starting to creep in and we were finding that it had become, as indeed festivals have been ever since, a place where there’s quite a lot of drug use. But it was all pretty new and experimental in those days. I just didn’t want to go that way at all. That was not my thing, so that was it. I just didn’t do any more.”

The Kon Tiki Folk Club of Hamilton seized the opportunity and staged its own Easter Folk Music Festival the following year, which is still running to this day and has affectionately become known as Hamsterfest. It benefitted greatly early on from the goodwill generated by the National Banjo Pickers’ Conventions.

Grace was one of the founding members of the University of Canterbury Folk Music Club in Christchurch in the late 1950s. Exponents of the long-necked banjo made popular by American folk singer and songwriter Pete Seeger, Grace and Hugh Canard were part of folk club groups that performed in coffee houses in the city as well as setting up bigger concerts at venues such as the Civic Theatre.

A sticker for a National Banjo Pickers’ Convention, drawn by Michael Grace. - Michael Grace collection

While working at women’s clothing manufacturer Cantwell Creations, Grace befriended workmate Clive Collins, a five-string banjo picker who was intent on bringing American bluegrass music to the Garden City in a series of bluegrass and old timey bands. The two became fast friends until Grace moved to Auckland in the early 1960s where he became involved in the fledgling Auckland University Folk Music Society formed by students Dave Calder and Len Cohen.

Meanwhile in Hamilton, banjo novice Paul Trenwith and guitarist Alan Rhodes had met in high school and were playing in a folk trio with Ted Ninnes while teaching themselves to play bluegrass music. When Calder ventured to Hamilton one weekend to visit a girlfriend, he listened to Trenwith and Rhodes’s Dillards records and became infatuated with the mandolin.

Through that contact, Trenwith and Rhodes were offered spots at the Auckland Folk Festival where they met Grace. He soon became a frequent Friday night visitor to Trenwith’s Te Rapa home where they would sit up all night and play music and where Grace imparted some banjo knowledge that would unlock the instrument for Trenwith.

The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band in action at the Claudelands showgrounds after the marquee at the Te Rapa site blew down at the 1968 convention; none of the 1200 people inside were hurt. Left to right: Colleen Bain, Dave Calder, Paul Trenwith (obscured), Alan Rhodes, Len Cohen, Lyndsay Bedogni. Photo credit: Trevor Ruffell (Michael Grace collection)

“He was a better banjo player than me because he actually knew what to do on it,” Trenwith remembered. “I’d sort of faked away and did a strange combination of sort of a strum and a picking pattern because I had no idea about anything really. He taught me a lick. He said, ‘This is what you’re supposed to do. This is a bluegrass lick.’ And he showed me it and by the end of the weekend I could do that pattern on every tune I ever knew and I could do it quite fast!”

It set the wheels in motion for Trenwith and by the end of 1966 he, Rhodes and Calder had brought together a six-piece bluegrass line-up that was eventually named The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band. Their self-titled debut album was released in early 1967.

The entire episode unfolded before Grace, but he was unperturbed. “That sort of thing didn’t interest me,” he said. “I had other things to do in my life than just be a road musician. Because of my particular nature and that I liked sort of organising and running things, I thought let’s have a bit of a session for interested people.”

“Do not blow or tap microphones.” An unidentified performer at the 1968 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention: it was the unknown acts who made the events work, says Grace. Photo credit: Trevor Ruffell (Michael Grace collection)

He struck upon the idea of a convention for banjo pickers and folk music enthusiasts where they could get together to share ideas and play music. With the support of Trenwith, Clive Collins in Christchurch and a team from the University of Auckland, planning for the newly christened National Banjo Pickers’ Convention began.

The inaugural event was held in Te Rapa on Easter Weekend 1967, just down the road from Paul Trenwith’s home – no doubt because of the ready access to the Te Rapa Hall; Trenwith’s father was the secretary and had a set of keys. The paddock next door was an ideal spot for patrons to camp in what became known early on as Scruggsville after banjo god Earl Scruggs.

Apart from starring with The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band and running banjo workshops, Trenwith was responsible for the toilets that first year. He collected builders’ shutters and built six bogs, digging the holes with a tractor and a drill before standing the shutters around them.

Banjo pickers and folkies came out of the woodwork from all over the country. Clive Collins was one of a number from the South Island who drove up individually, crossed Cook Strait by ferry and continued to the Waikato.

Soundman John Ruffell described himself as “an okay banjo picker” at that time. By the age of 16, he had already begun recording local theatre productions as a hobby in his home town of Hastings. He moved to Auckland to study physics at the University of Auckland but kept up his interest in recording and started getting hired for commercial productions, especially in location work due to possessing his own portable equipment.

At the 1968 convention John Ruffell (left) and Robin Gummer not only mixed the live sound but also recorded the entire proceedings for albums of highlights from the conventions later released by Kiwi Records. “They were stalwarts,” says Grace. “Without that technical import it would never have been what it was.” - Michael Grace collection.

When he and Robin Gummer weren’t mixing sound at the convention, Ruffell managed to pick up some pointers from the other banjo players there. “Right from the word go, we had a multi-microphone, stereo set-up,” Ruffell said. “I think we were running a stereo pair and a little cluster in the middle, and we were running at least two side mics and then a bass mic. So, you know, a reasonable set-up, and doing live balancing on headphones.”

National Banjo Pickers Convention 1968 LP, Kiwi label. - Courtesy of RNZ.

National Banjo Pickers Convention 1969 LP, Kiwi label. - Courtesy of RNZ.

National Banjo Pickers Convention 1970 LP, Kiwi label. - Courtesy of RNZ.

Ruffell had been building a reputation with the New Zealand record labels as a freelance engineer and casually mentioned to Kiwi Records owner Tony Vercoe that he intended recording the 1968 National Banjo Pickers’ Convention. The label head was immediately interested and Ruffell persuaded Gummer to bring his homemade tape recorder to capture the performances.

The convention had outgrown the small Te Rapa Hall and Grace decided the main concerts in 1968 would be held in a huge circus tent in a paddock nearby. In the lead-up to the event the tent city known as Scruggsville was described in the South Auckland Courier as “a shanty town of caravans, tents and marquees, with streets marked by ropes”. The “streets” were named after folk singers and groups.

What Grace and his team and the population of Scruggsville could not have envisioned was the high winds and torrential rains brought by ex-Tropical Cyclone Giselle that covered the entire country in the second week of April and sank the Lyttelton-to-Wellington ferry Wahine on the Wednesday before the festival.

On Easter Sunday, during the afternoon folk concert under the big top, the wind was “a screaming gale”. The New Zealand Herald of 15 April 1968, reported: “The wind got under the marquee, snapped guy ropes and ripped the tent almost from top to bottom. One of the two steel main supporting poles was badly bent and the other, taking the full weight of the wet, wind-bellied marquee, bent like a fishing rod.

Square dance caller Thelma Blyth fronts the Palmerston North Bluegrass Band at the 1968 square dance. Blyth was a star of the TV show Country Touch, and arranged and called the Old Time Country Style Square Dances at the conventions. “The square dance was a major event each year,” says Grace. “They had such an impact, they were such a lot of fun.” Photo credit: Trevor Ruffell (Michael Grace collection)

“For several seconds there was near-panic among the 1200 inside as wooden supporting poles snapped and the marquee sagged and started to collapse. But spectators standing to the edges of the marquee grabbed the flapping canvas and held it down against the force of the wind while others shepherded the crowd outside.”

John Ruffell and Robin Gummer leapt to secure their gear hired from a sound company in Auckland. “Robin dived to protect his equipment and I sprinted for the stage to try to manage an evacuation,” Ruffell recalled. “But the tent came down too quick and so I confined myself to saving the microphones.”

Three months after the 1968 National Banjo Pickers Convention, the organisers ran a square dance at the YWCA Auckland. Michael Grace, who hand lettered the flyer designed by Carole Shepheard, says: “The square dances were more an emotional event for those present, rather than something you'd drive across town to attend.” - Michael Grace collection

While the tent was collapsed, the concert resumed acoustically in the overflowing Te Rapa Hall. But it was clear the organisers had to find a new venue for the main concert that night. Grace telephoned the Mayor of Hamilton, Denis Rogers, who arranged for the Waikato Show Trust’s new buildings at Claudelands.

“I knew we were gonna try to go somewhere else,” Ruffell continued, “so we were crawling around on canvas trying to roll up cables and microphones and get all the gear out, and had some helpers sort of propping up the tent, standing there like human poles so that we could work. And by the time we had the stuff out and sort of more or less safely packed, Michael said, ‘Well, we’ve got the hall at Claudelands.’”

Miraculously the equipment was transported, performers assembled and audience informed of the change of venue and the main concert started at 8pm on the dot.

1968 was the first year Kiwi Records released a highlights album. Ruffell’s brother Trevor took the photographs on the cover and the record included tracks from The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, The Mad Dog Jug Band, The Palmerston North Bluegrass Band and Clive Collins and Jim Doak among others.

As the live performances were going to tape, John Ruffell would put check marks and asterisks in a scruffy notebook listing the programme. In the days and weeks following he listened through to the results and his initial scrawlings were nearly always spot-on.

If anything, the convention’s attitude of not letting the weather get the better of it added to its legend. Waikato local bodies were practically falling over themselves to host it and in 1969 Ngāruawāhia seduced the organisers. The main stage was a shingle barge moored in the Waikato River. The Friday night concert was held in the Ngāruawāhia picture theatre.

Mike Seeger performs on the barge moored on the Waikato River at Ngāruawāhia for the 1969 National Banjo Pickers' Convention. Photo credit: Trevor Ruffell

For the first time, Grace booked an overseas artist, flying in American singer and multi-instrumentalist Mike Seeger, half-brother of protest singer and songwriter Pete Seeger. On tour in New Zealand the year before, Pete Seeger had donated US$100 to the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention.

His younger brother Mike was a founding member of the New Lost City Ramblers and played all sorts of instruments including guitar, mandolin, autoharp, banjo, fiddle, dulcimer and, as he showed at Ngāruawāhia, spoons. He was enamoured of the entire riverbank scene. Whilst performing in the rotunda he announced how much he was enjoying the event and how he loved the beautiful setting and seeing the old cars. “What do you mean old?!” shouted a wag in the audience.

Not a banjo to be seen in this 1968 shot; instead, guitarists enjoy a workshop. Hamilton County Bluegrass Band member Len Cohen goes high on the fretboard. Right of him are Country Touch regulars Paddy and Chris Lydon and HCBB fiddler Colleen Bain. Photo credit: Trevor Ruffell (Michael Grace collection)

Hamilton County Bluegrass Band mandolin player David Calder remembered attendees of all abilities falling under Seeger’s spell and he was especially impressed by the American’s mandolin. “It was the first Gibson F-5 ever seen in New Zealand with a blond body, and the most beautiful instrument I’ve ever played. His Gibson Mastertone banjo was the best Paul had ever played, too. Mike played all his instruments better than us and we all learned new licks and chops.”

The addition of an international act did affect the cost of attending, though. The 1969 programme read: “The cost of the NBPC 1969 is similar to the NBPC 1968, except that there are the additional expenses of flying Mike Seeger from and to the US. If each conventioneer would be prepared to pay $1 towards this extra cost, we will cover our outlay. For this reason the price of a concession ticket will be $3.50.”

A concession ticket brought continuous, unrestricted access to every activity, a campsite at Scruggsville and admission to the opening concert. The tent town Scruggsville had grown considerably with each convention and was the responsibility of engineer Jeff “Ben” Bendall. He looked after security and the practical matters of the site and the concert venues and anything else that came his way.

This was the first convention where the unruly behaviour of a small group began to impact proceedings. In her report for the May 1969 edition of Heritage: New Zealand's Folk Magazine, Sharyn Harris wrote of the opening concert, “I was disgusted by the drunken behaviour of some of the audience and can find no excuse for the rude reception given to some of the performers.”

Registrations topped 1000 and had to be restricted, and the Saturday night square dance had to be limited due to space. The final concert was again held at the Waikato Show Trust Building at Claudelands with locals swelling the crowd to an estimated 4000.

Harris finished her report with the warning, “The convention has grown in size so much in three years that next year or the year after, the size is going to have to be limited. If it grows much bigger than it was this year, it will detract from its purpose in that more people will be unable to attend some of the attractions due to lack of room.”

Recording engineer Robin Gummer had taken a job in Canada, so John Ruffell had to make do with the recording equipment he’d accumulated and manage the live and recording mixing simultaneously. “Basically, the live sound became the recording mix,” he said. “You know, we couldn’t really do it separately.

“With Robin and I working together, I was able to tweak the live sound a little bit independent of him working on the recorded mix, but when I was on my own I just fed the recording mix through the sound system, and we didn’t have any complaints!”

The 1969 highlights LP included performances by the newly professional Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, Mike Seeger, Vernon Dalhart's Cornfield Symphony Orchestra, George Stewart and the Mainland Hoedowners and Clive Collins’ new outfit The Stoney Lonesome Boys, who had shared the driving from Christchurch in Collins’ Vauxhall Cresta with Collins’ wife Lesley and baby son Carl along for the ride.

The final convention, at the Claudelands Showgrounds in 1970, was the subject of the Daisy Films feature Keep On The Sunny Side, produced by Bob Harvey and directed by Warwick Brock (see link below). The international guest was American bluegrass musician Bill Clifton who had spent the mid-1960s touring in England before joining the Peace Corps in 1967 and serving three years in the Philippines.

Three months after the windswept 1968 convention, Grace hand-lettered an invitation for fellow organisers to attend a reunion dinner in Auckland. - Michael Grace collection

“That was the first one that got well beyond being a banjo convention,” Paul Trenwith recalled. “The music was becoming more pop-folk oriented. There were some bluegrass bands, like Hamilton County and Clive’s band from Christchurch (renamed Stoney Lonesome) doing some lovely stuff, but there was also jug music and soloists and it was much more of a folk festival.”

The 1970 highlights LP on Kiwi reflected that view, with Tamburlaine’s Steve Robinson performing The Beatles’ ‘Rocky Raccoon’ and Tamburlaine, credited as The Tamburlain, contributing James Taylor’s ‘Something’s Wrong’ and Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘The Only Living Boy In New York’. Marion Arts also appeared with Bob Dylan’s ‘It Ain’t Me, Babe’ among the bluegrass staples of Clifton, The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band and others.

The escalating intricacies of musical arrangements and the introduction of electric bass guitars by Tamburlaine and Stoney Lonesome in 1970 kept John Ruffell on his toes. “I had a lot of fun with the technical challenges,” he said. “Some of the scale was beyond anything I’d done before, and I certainly enjoyed that.

Beneath the Claudelands showgrounds grandstand, 1968, Hamilton County Bluegrass Band mandolinist Dave Calder and his wife Andrea, who also produced their own album under the name David and Panda. Photo credit: Trevor Ruffell (Michael Grace collection)

“It had got too big and there was no way that we could think of to try to get it down to a more select group. It was becoming more and more like a weekend party. And, you know, a lot of good people; we didn’t have a lot of fighting or thieving or anything, but it was getting away from the original focus, which was getting musicians together to have fun and share their skills. So, it was kind of hard to know where to take it.”

For Michael Grace there was only one conclusion. The event had surpassed all of his expectations and the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention had gone far away from his initial concept. There was no romance, he just shut it down with a celebratory dinner for his faithful team at an Auckland restaurant.

Ruffell did heed the call to mix sound and record the first Easter Folk Music Festival the following year but nothing came of the recordings. By that stage, The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band had set up in Sydney and were readying for a trip to the United States at the invitation of Mike Seeger. They would remain in Australia until late 1972 before returning to New Zealand and disbanding after filming TV series Country Road.

Life after the banjo conventions was never dull for Michael Grace: they led to a “much more interesting” career than his studies in accountancy promised. He found success in various fields including visual arts in Auckland and the QEII Arts Council and the Council For Recreation and Sport before managing the establishment of the New Zealand Coastguard Federation.

--

Read more: Duelling Banjos – a photo album from the National Banjo Pickers' Conventions.

Read more: Banjos at Dawn – scenes from the National Banjo Pickers' Conventions.