In New Zealand there is only a handful of independent record companies, and even fewer who release more than one or two titles per year. Ode Records has been in the business of recording New Zealanders for nearly 20, and if Terence O’Neill-Joyce has his way, they’ll continue to do so for 20 more.

An acquaintance of Terence’s once asked him what he did for a living, and he replied, “Oh, I run a record company.” “Which one?” asked the man. “Ode,” said Terence, at which the acquaintance shrugged “Oh, I’ve never heard of it.”

“I operate as a conjugate,” says Terence. “My wife’s an artist, I write. I can understand the creative process, and the best conditions for being creative are when things are open and free. There’s a lot of bullshit in the record business with people superimposing their ideas of how things should be done, you know, with groups going into the studio to make their record. I hate to think how disenchanted some of them must be when they finally get the finished product.”

Terence O'Neill-Joyce, Book of BiFim, 1987.

Terence sits behind the desk at the Ode office. It’s a less-than-flash setup behind the hum of K Road. Out the office window, downtown Auckland bustles while I manage to get the tape recorder rolling.

O’Neill-Joyce started Ode Records back in 1968 after working for five years at HMV (later called EMI) and Festival Records in Wellington. He had also been employed for a time at the (now non-existent) Radio Corporation of New Zealand, the founders of Tanza, who had their own pressing plant in Courtenay Place.

“There were some interesting things happening in the 1960s with New Zealand music, with a lot of entrepreneurial activity on the mechanical side of the industry.”

In those days the mainstay of record pressing in the country was the HMV plant in Wellington but, unlike today, there was also a number of smaller plants operated by various people. The Tasman Vaccine Laboratory operated out of Wellington’s Victoria Street with a small studio and cutting room (later becoming Lotus, before being bought by HMV). At one stage, a plant operated out of Kelburn.

“There was at that time a lot of activity, the whole radio station situation was really open and cooperative, most of the music being done was by people like EMI, who had at that time two resident producers. Can you imagine that happening now? One record company having two producers? There’s no record company that even has one resident producer today.”

In early 1968 Terence decided he’d had enough of working for other people’s record companies, but after his first release, ‘Sally I Do’ (performed by Abdullah’s Regime), he found that he had to go back to work to survive. After three months, he was back with Ode, this time for good.

“The lesson that I learnt was to keep one foot in the camp that could supply me with enough money to maintain myself, the family and the mortgage.” At that time he would record an act and then pass it on to one of the larger recording companies.

In the Blue Vein - a compilation LP of Wellington blues acts, released on Ode in 1969

After a few years, in which he continued leasing acts and had set up a record shop, he decided to move to Auckland.“What astonished me about the move was that I could sell more in one day in Auckland than I could in a month in the South Island.”

By now it was the early 70s, and the move to the big smoke helped in many ways to speed up the establishment of the label. The Ode stable at that time boasted acts such as the Dizzy Limits, Nash Chase, and the late Prince Tui Teka.

“Prince Tui Teka paid the rent for quite a while. He was brought to the attention of Philips by a hotel owner in Hastings. At that time John McCready was the A&R man for Philips, he rang me up and said ‘We’re not really interested in this sort of thing, but maybe you’d like to do something,’ so I went to see him perform, and the man was such a great performer.’

With Prince Tui Teka signed to Ode, Terence released a single of the great man which has, over the years, sold in excess of 50,000 copies. “The amount seems even more staggering when you consider that [in 1987] a single can hit No.1 with sales of less than 1000, and that most of the time companies struggle to sell even a few hundred.”

That’s an achievement that Terence is adamant could not happen today. “It would be impossible to sell that number of singles, simply because the market has changed a great deal since the early 70s. In the US compact discs are beginning to outsell records while in New Zealand, singles are now seen as merely a promotional tool aimed at radio stations.

Prince Tui Teka's debut album for Ode, released in 1974.

“I’m not happy with the idea of spending money to make a record just to satisfy a radio station that won’t play it anyway.’

This is an attitude shared by most independent recording companies, plus some of the multi-nationals who deal with local music. Given the state of affairs, the records that Ode does release tend to be in the EP or LP format but, as with some other labels, Ode sells more cassettes than it does records.

“We sell lot of Pacific Island music and we just don’t do records because they don’t have any record players to play them on. We also do people like Michael McGifford which is mums’ and dads’ music, and I guess that mums’ and dads’ record player has worn out or they can’t find a replacement needle, and they’ve had their trips to Fiji and Rarotonga and they’ve got their cassette players. In 10 years, records will be collectors’ items.”

Although a lot of Ode’s output is of local groups aimed at the local market, a great deal of Terence’s interests lie overseas. Wanting to import records in the mid-1970s he found himself with a problem. As the law stood, you couldn’t obtain an import licence unless you were really big or you had a history of exporting. So he began looking at overseas markets, and a friend with relatives in Suva providing a starting point.

“I realised that in Fiji there was plenty of music for the Indians, which came out of a place [in Greater Kolkata] called Dum Dum EMI India, but there was no music for the Fijians other than music that people like Viking had recorded but that wasn’t for the Fijians, it was for tourists.”

Armed with a Revox tape recorder and a camera, Terence worked on a number of projects in Fiji. Upon returning with the tapes and photographs of the groups, he began the process of mastering and packaging the music to re-export to the islands. At one time, he estimates that the potential market to Fiji was in excess of $1 million but within the space of a few years, the government in Suva imposed heavy duties on imported music, even if it was recorded in Fiji.

Timberjack-Donoghue's 1975 album Donoghue (Ode). Produced by Terence O'Neill-Joyce and backed by Redeye with the Yandall Sisters on BVs.

With the closure of the Fijian market, Ode began to look at other Pacific Island nations and more recently to China. The idea to look at China came from a friend of Terence’s who was a member of the Porirua Brass Band. It seemed that the Chinese were extremely interested in the touring New Zealand brass band and indeed had many brass bands of their own. After initial contact through a Chinese trader in New Zealand, he followed up the idea while attending a trade fair in France where the China Record Company had recently begun to exhibit. With the opening up of China to the west came the very first trade fairs outside China. It was through these fairs that Terence managed to sell a very large quantity of New Zealand music, from brass bands to pop groups.

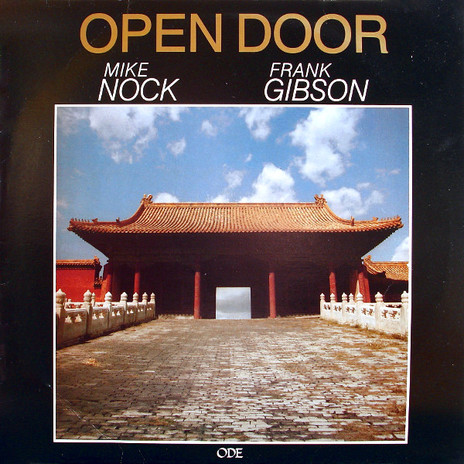

In New Zealand, Ode could safely be called the home of jazz, so it was only natural that much of the sales to China could come from the Ode jazz stable, with some of it packaged to suit. “‘I’d recorded Mike Nock and Frank Gibson. I’d called it Open Door and I had a picture of the Forbidden City on it. At a meeting before the last trade fair I was astonished because they actually gave me an order for it then and there, which is a very unusual practice in China.

Mike Nock and Frank Gibson - Open Door (Ode, 1987), photo by Terence O'Neill-Joyce.

“So there I was with an LP by two Kiwis with some of the song titles in Chinese and the Forbidden City on the cover, and it felt good. It was like the spirit of cooperation between the two countries had come together in this project.”

Back in New Zealand, Terence is adamant that the growing number of young artists he has been releasing will continue to grow. They may not be money spinners but, as I find out, for Terence profits are a tool rather than a goal.

Terence O'Neill-Joyce and NZ On Air's Brendan Smyth - Photo by Jocelyn Carlin

“I really work as a framework for the bands to work through, it’s not as if I sign them up, as long as we can do it on an economic basis and I’m not running at a loss we can keep doing it. So I’m really excited and encouraged at the ability of young groups to put together a package, both the graphics and the recording techniques. I’m really quite excited!”

Something that doesn’t excite Terence O’Neill-Joyce is putting his radio on. “I just can’t accept that there isn’t a greater place for New Zealand music on radio, a New Zealand voice.’

But there is one part of the country where he believes that radio (student radio aside) is different – in Dunedin. It seems that even when New Zealand radio was mostly a desert, orders for Ode records almost always came from Dunedin.

“Sometimes it stood out so much that we’d track it down and find out that someone had gone into a record shop because they heard the song on the radio. There’s this Dunedin attitude; if the whole of New Zealand had a Dunedin attitude it would be, I won’t say better, but more healthy.”

“I remember going there years ago trying to find Begg’s record store or something. I caught the bus, and the driver even went down an extra street and dropped me right outside the shop. Can you imagine that happening in Auckland?”

--

This first appeared in BiFiM, August 1987, as “Good Ode Days”, and is republished with permission.

Read more: Ode