I’ve been looking for and listening to New Zealand synth music for close to 20 years, ever since I found a near-mint copy of the second vinyl pressing of Douglas Lilburn’s The Return and the Elegy at Dunedin’s famous Regent Theatre book sale – for 50 cents! And I was tantalised by the magical neologism “Sound Image and Music by Douglas Lilburn” under the title. I’d never heard of Lilburn then, being a newby Zealander, but the idea of a “sound image” – combined with the pop-psych kowhaiwhai cover art – tipped that this was something other.

The Return and the Elegy (Poems by Alistair Campbell, Sound Image and Music by Douglas Lilburn), Kiwi, 1967.

There’s not a lot of non-academic synth-based music from New Zealand pre-mid-80s. Synthesisers were bulky, weird and new – and really mostly just crazy expensive, particularly with New Zealand’s punishing import duties. The In-Betweens had one, Mike Harvey had a couple, Steve McDonald had a big pile. Mammal though, had to ask the Electronic Music Studio at Victoria University to add some synthesised wind sounds to their 1972 album with Sam Hunt.

Much like the NZ psych rock of the late Sixties — which was mostly drunken imaginings of what drugs might be like – the innovative scene in the antipodean 80s, dominated by DIYers and justified with typical levels of pop/rock snobbery, played cheaper portable organs when they needed keys.

Narrowing this very personal best list to just 10 key moments of synth music history is challenging enough, especially considering the critical importance of highlighting and amplifying the work of women, indigenous and queer producers. A lot of deserving folks like Car Crash Set and The Body Electric, Mi-Sex and Split Enz, Ragnarok and Airlord, Fetus Productions and The Skeptics, Headless Chickens and Strawpeople just didn’t make the cut. I’ve also focused on the hardware era of synthesis – actual black and tan boxes with cables, knobs and keys – so some software synth slingers and dance artists from the turn of the millennium were left in the box.

Starting with our first recorded piece of synthesised music, this list finishes with a musician who embraces antique spacies and generations of underestimated e-instruments – and along the way we celebrate our garage rock and bedroom pop, festival trance and Pacific breakdance, post-folk and folkloric prog, home-baked circuits and cosmopolitan cool.

--

1. Douglas Lilburn – The Return (1967)

Douglas Lilburn in the Electronic Music Studio, Victoria University, Wellington. Dominion/Evening Post collection, EP/1969/3689/18-F, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Godfather to both New Zealand classical and electronic music, Lilburn founded Victoria University’s Electronic Music Studio in 1970. But a few years before that he used field recordings, noise generators, filters and ring modulators to manipulate and score this poem by Alastair Campbell. More an example of the musique concrète style – the synthesiser as we know it barely existed at this point – once he began fiddling with electronics, Lilburn all but abandoned traditional composition for classical instrumentation. He wrote in his A Search for Language, “I’ve found it exhilarating and liberating to work in this new electronic medium and explore unfamiliar regions of sound. Significantly, perhaps, I’ve been able to produce sound tracks for several plays based on Māori legends, making the textures from human voice, natural and electronic sources, and doubt whether I could have done this with any conviction using conventional European instruments with their weight of older associations.” The bygone songs of extinct birdlife, and a modulated te reo recitation of the trees of our forests, float through dramatic flare-ups of gongs and guiros, seagulls and albatross; crashing cymbals commingle with splashing waves and white noise whitecaps, while in his best BBC baritone our narrator Tim Eliott intones Campbell’s poem about the “rain-jewelled, leaf-green bodies” of the “plant gods, tree gods, gods of the middle-world … ”

Watch: TV footage of Douglas Lilburn in his Electronic Music Studio, Victoria University, 1970.

2. Mike Harvey – Cauldron (1978)

For fans of Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds (and its star vocals from New Zealand’s own Chris Thompson) of the same year. ‘Cauldron’ – on Mike Harvey's 1978 album Great Expectations – is a slice of narrative-driven instrumental synthpop not heard again till Stef Animal’s Top Gear album 40 years later. A gifted instrumentalist and producer, Mike Harvey worked with Golden Harvest and John Hanlon, and was inspired by the funky prog yarning of Alan Parsons’ Asimov and Poe concept albums. Here on his solo outing, he’s joined by long-term collaborator Martin Winch, two Dudes (Ian Morris and Dave Dobbyn), and vocalist Lea Maalfrid from fellow synth-proggers Ragnarok. An electric bass line, combined with the hiss of compressed-air cymbal spits and phased click-rhythms, backs a monolith of mono-synth multitracking: staccato brass stabs and a slippery lead-tease out a melody that alternates between twee and triumph. Probably the first pop track entirely produced on synthesisers in NZ history.

3. Patea Māori Club — Poi E (1983)

Dalvanius and co-producer/engineer Dave Hurley working on Poi E by the Pātea Māori Club. - Photo courtesy of Sue May.

Our unofficial national anthem is a synth song! A powerful waiata, rousing and cautionary – and famously a singalong that almost no one knows the words to – ‘Poi E’ just wouldn’t be the phenomenon it is if the producers hadn’t dropped that danceable drum machine and squirts of analogue synth into the mix. All recorded in one hour-long session, with a burbling Oberheim bass line and a LinnDrum borrowed from Alastair Riddell, it’s driven by that rhythm, and punctuated by synthesised guitar on the upbeats. Co-writer Dalvanius described the sound to the New Zealand Folk Song website as “a hybrid of our rural roots and urban influences … a product of the urban drift when our rural jobs were lost.” Considering his memorable insistence on the addition of Space Invaders sounds, it could’ve been a one-off novelty number but is instead an agency of grace: where the electronic technology of the 80s finally caught up to the electrifying voltage of traditional Māori voice.

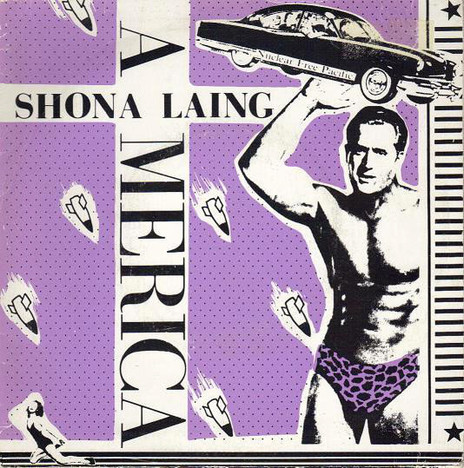

4. Shona Laing — America (1985)

Shona Laing - America (Pagan, PAG 1001, 1985)

A prodigy who recorded her first Top 10 single and two widely admired full-length albums while still in her teens, Shona Laing bucked the establishment from the inside while straddling the most powerful trends of the moment. Her breakthrough single ‘1905’ is a classic of the 70s sensitive singer-songwriter style, showcasing Shona’s bold voice and precocious songwriting. By the mid-80s she’d returned from the UK and a stint in Manfred Mann’s Earth Band to fully ground the new synthetic sound she’d explored on Tied To The Tracks (1981) – the pioneering icon glaring back at the camera in a punky goth-mullet and a black trench coat. The first single on Trevor Reekie’s new label Pagan – and the leading track on Genre, her first New Zealand album of the 80s – ‘America’ has a minimal-wave bass line, synthetic horns, shimmering lead and doomy pads, Simmons drum fills, and an absolutely exemplary 80s guitar solo. The rest of the album is rich in synths, a sound she continued to explore on her biggest hit ‘(Glad I’m) Not A Kennedy’ from sophisticated follow-up South (1987).

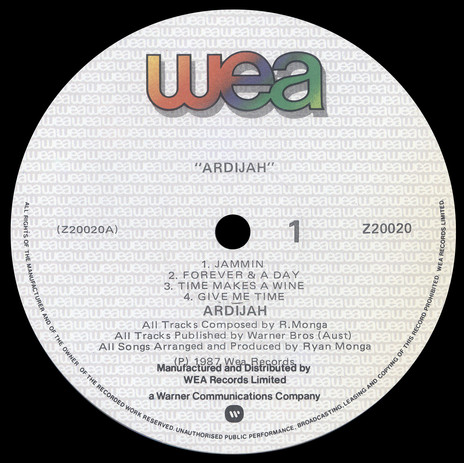

5. Ardijah – Forever and a Day (1987)

Label for side one of Ardijah's self-titled debut album, WEA, 1987

Ardijah was a rare band for technology-starved 80s New Zealand, getting their start with a drum machine and a ghetto-blaster, following Prince’s lead into electro-funk to create their own genre, the Pasifika-infused Polyfonk. It’s a challenge to choose just one track from this legendary act, but this deep cut from their first full-length is a slice of synthesiser transcendence. Betty-Anne Monga’s incomparable vocal is chaperoned by machined handclaps with just the right amount of swing. Ryan Monga and crew craft the track around a bass melody, with the DX-7 dropping icy pads, tinkling chimes and that oh-so-80s e-piano, all underpinned by a tasteful pizzicato rhythm guitar. A singular sweetheart from the impeccably produced waka huia of their self-titled debut.

6. The Terminals – Basket Case (1992)

The Terminals in the early 1990s.

Founders of the lo-fi garage scene of The Futurians, Pumice et al, The Terminals grew from the writing partnership of the late Peter Stapleton and Stephen Cogle in The Victor Dimisich Band. Mick Elborado is the permanent third Terminal with Stapleton and Cogle, in a band which saw folks like the Heneys from 25c and the Crooks from The Renderers pop in and out. This opening track from their second LP Touch, ‘Basket Case’ showcases the Ravenstine-ish Tesla coil cyberman shrieks of clever-clogs keys-freak Elborado, bouncing sparks off Brian Crook’s unconfined fuzz guitar. Here he commands battle helicopters vs UFOs, describes isobar maps for the blind, receives chrome-plated 3-D communiques from the galvanic dinosaur swamp and sets the alarm clock which triggers the magpie’s guillotine – all from the same haunted Moog played by Janine Stagg in Dadamah, which was later lost in a fire that destroyed Stapleton’s home at Purakaunui.

7. micronism – rainbow city (1998)

A bedroom producer based a few blocks from Kog Transmissions’ Kingsland HQ in the late-90s, Denver McCarthy made acid bangers for ecstatic ravers as Mechanism. He adopted the lower-case sobriquet “micronism” for the devotional deep house record that was his transition to “full Krishna”. In the nostalgia-drenched 21st century, micronism’s synth list reads like a who’s who – or a what’s what – of vintage gear: Roland drum machines and synths such as the CR-78, Juno-106, MC-202, TR-909; Boss Heavy Metal and Sovtek Small Stone pedals … Yamaha, Korg and Akai ... oh my! McCarthy told The Spinoff when Inside a Quiet Mind was recently re-released, “this is just the sounds of some synthesisers made in Japan, but it evokes such a deep emotion”. Constructed computerless with just these machines, ‘rainbow city’s’ rapid arpeggios squelch and rumble like the underwater hookah-bubbles of a benevolent Burroughs centipede god.

8. Bachelorette – Complex History of a Dying Star (2006)

South Island space-gazer Annabel Alpers’ sophomore cosmic simulcast, Isolation Loops – though nominally solo – seems to summon the celestial support of fellow stellar travellers, from the psychedelic folk of Linda Perhacs to UK post-rockers Pram. Having chauffeured a metric truckload of vintage keyboards to an uninsulated coastal Canterbury hut, Alpers set about building her wispy, whispery electropop dispatch from old school synths – and hither and yon, some real guitars and drums. On the album’s penultimate cut, Alpers’ breathy vocals coalesce across an abyss of hissy digital reverb and a sawtooth bass line boogaloos in like ball lightning, introducing the sound of muted tubular bells.

9. Omit – Live @ Bar Medusa, Wellington (2012)

Omit - Live at Bar Medusa, Wellington (2012)

No list of New Zealand synth history is worth its solder without honouring Clinton Williams, aka Omit. Based in avant-backwater Blenheim, for more than 30 years Williams has reworked electric motors, abused prosumer production tools, exhumed obscure synths, cracked everyday electronics, and hand-built whizz-boxes for his visionary synthesis. Squirt-sizzle rhythms and rusty hinges pivoting in dim chasms evoke a transcendental dread. The Omit design aesthetic is cryptic: stippled, brindled Giger-esque figures and Cardew-y graphic scores adorn his cassette covers and comics, lathe-cuts and CD-Rs. Body-horror ambience for a Cronenberg chill-out room.

10. Stef Animal – In The Pines (2018)

Stef Animal - Top Gear (2018)

Track two on Top Gear, her audio love letter to forgotten tech, Stef’s transistor-and-thermoplastic slant on an old-time tale of railroad decapitation is far from the Louvins’ or Lead Belly’s traditional folk takes – but it’s an equally tragic song of life. Through lyricless, Ms Animal’s voiced “la-de-da”s draw a desolate track with the melancholy of Bill Sutton’s Plantation Series paintings of the 80s: fecund green-black shadows slashed on golden lands. But hark, a brassy bastion bellows out via the keyboard’s kitschy trumpet preset. Full disclosure: I swapped this synth – an SK-1, my teenage Casio – to Stef in 2005 for a distortion pedal, so I especially relish this song she’s spun from the now-classic near-toy.