For years, Brian Murphy was the guy who carried a camera everywhere, capturing his musician and artist friends as they performed, practised and partied. Most of the pictures were never printed, let alone published. But several years ago, he returned to what has proven to be a remarkable archive.

Blue Marbles, probably at the Royal International Hotel. From left: Pip Brophy, Carolyn O'Neill, Steph Rowe, Greta Anderson and Deb Frame. - Brian Murphy

Murphy arrived in Auckland in 1983 and, after seeing the French film Diva, in which the bohemian Gorodish lives in a huge urban warehouse, decided that he, too, should live in such a space. It was an unusual wish at the time. The central city was sparsely populated and bylaws made converting commercial spaces difficult.

But he found a place, taking the lease on the third floor at 45 Anzac Avenue, above Progressive recording studio. The former office space had a kitchen and a bathroom, but few internal walls, and most people entered via the kitchen window, which faced the rear of Brooklyn apartments.

He found flatmates, including musicians Gavin Buxton and Dave Majors, and Lisa Coleman, who later toured with The Chills as the band’s lighting engineer. Other connections led to friendships with Kirsty Cameron and other visual artists. Through them he found a new community.

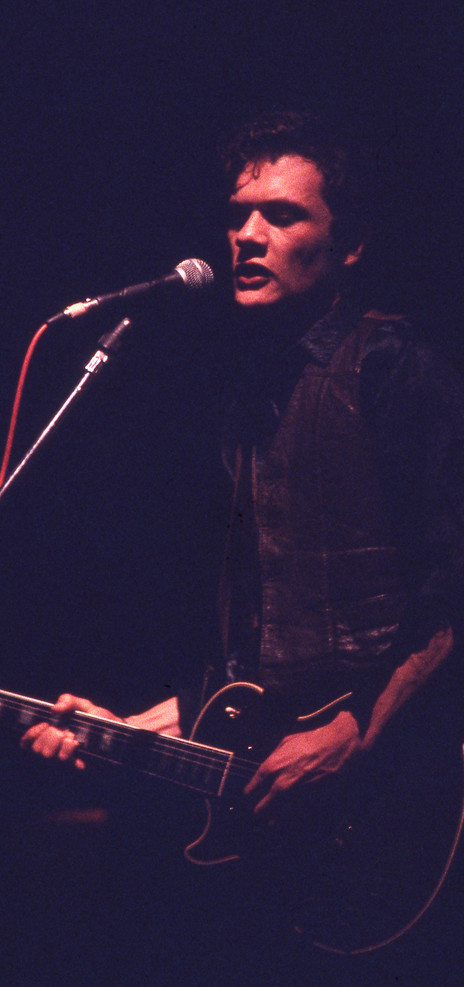

Rupert E. Taylor of the Headless Chickens. - Brian Murphy

The size of the space made it ideal for playing music. When the Sam Ford Verandah Band reformed for a 1984 tour with The Topp Twins, the band and the Topps rehearsed there. The studio below was in its heyday and when the Able Tasmans recorded their debut EP The Tired Sun at Progressive, the flatmates were summoned down to make miaowing noises for the song ‘Nelson the Cat’. The flat had its own band too: Buxton and another flatmate, Dave Majors, were the core of the Ponsonby DCs.

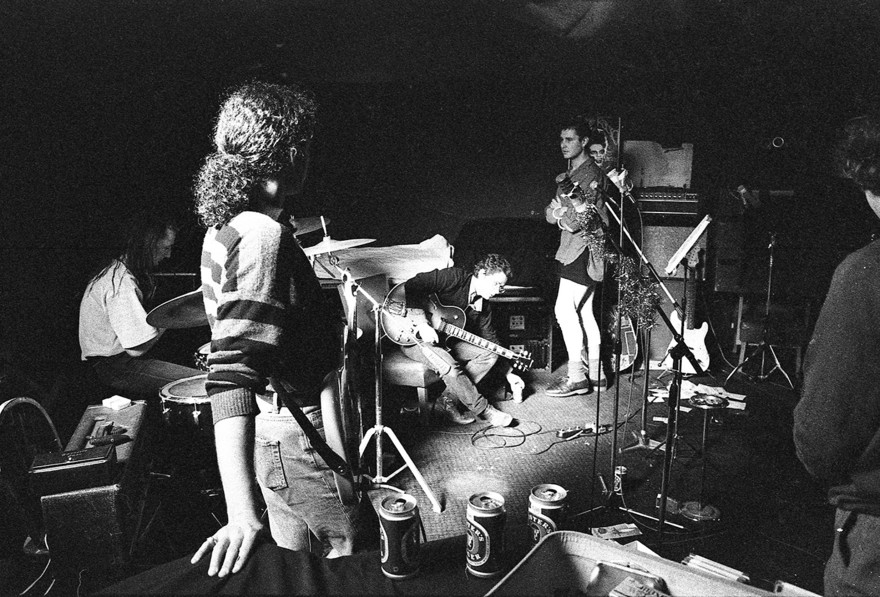

The Membranes, c. 1984. From left: Dave Major, Gavin Buxton, Otis Mace, David Eggleton playing at the legendary Anzac Ave flat. - Brian Murphy

“All sorts of people came through,” Murphy recalls. “It was great, really interesting. And having the studio below was fine. Except when The Gordons were there. Then the noise just came everywhere.”

Murphy wanted to play his part too. “I had flatmates and friends who were musicians. And I wasn’t a musician – but I could go along and take photos. That was something that I did know how to do.”

At the New Station Hotel for a Skeptics gig. Faces in the crowd include Robert Key, Rachael Churchward, Bob Sutton and Shayne Carter. - Brian Murphy

He was making good money as a computer operator, so he bought first an Olympus OM2, then a Canon T90, “which was at the time a really futuristic sort of camera. I think it cost me about $1400 in 1984. But I was working shifts as a computer operator, getting paid more money than I could drink. It seemed crazy at the time spending so much money on a camera, but I’m glad I did.

“While I was taking photos, film improved a lot as well – and I guess what I could afford improved too. Ilford XP1 film, which you could shoot in the dark with if you pushed it, sensitive slide film, things like that.”

When he finished a roll of film, he’d get it developed and have a contact sheet made, but access to darkroom facilities was sporadic, and most of the time that was it.

Bob Sutton with his video camera at the Skeptics show. “It’s been interesting watching [TV doco series] Anthems – you see quite a bit of Bob’s stuff on that. Me and my photos, him and his videos and people like Shayne Carter and Graeme Jefferies writing books. It’s good.” - Brian Murphy

David D’ath of the Skeptics, New Station Hotel. - Brian Murphy

“I did get a couple of photos published in the Auckland Star, but I wasn’t trying to make a living out of it. As much as anything, it was just trying to do things that were supportive of my friends that were musicians.”

Murphy played a role in the scene in other ways – notably as the stage manager for the two ground-breaking multimedia shows produced by members of the Headless Chickens, The Nitpicker’s Picnic and The Happy Accident.

Goblin Mix at the launch of the Jesus on a Stick comic. - Brian Murphy

“It was actually really nice. I got to meet a lot of new people, helping them do things, running things on and off stage. It was just a good way to get know more people.”

Murphy moved on from the Anzac Ave flat, although subsequent residents (including the author of this article) continued its traditions of music and memorable parties. And eventually, the negatives went into their boxes and were forgotten for 30 years.

Jed Town and Sarah Fort as Fetus Productions, the Windsor Castle. - Brian Murphy

But about five years ago, Murphy got a negative scanner and shared a few images with friends, to an enthusiastic response. The reopening of the archive proved timely: the beautiful picture of Grant Fell on the cover of the booklet for Grant’s funeral in 2018 was one of Murphy’s, printed to paper for the first time.

Grant Fell. - Brian Murphy

“I was very lucky to still have the negatives,” Murphy acknowledges.

There are now about 1500 images scanned and they make up a collective picture of an inner-city arts and music culture at a time of change.

“I suppose it was fairly recently post-punk and there were a lot of people just doing it themselves,” Murphy recalls. “Coming up with performance, with a show. People performed all over the place. And of course, it was a completely different city to what it is now.”

--

Headless Chickens in their practice room in Galatos Street. “I took a lot of pictures of the Headless Chickens. I’d just hang around with them, go out drinking or whatever. But while I was there I’d take some pictures. It was what I did, I guess.” - Brian Murphy

The Headless Chickens and a set designed by Jaq Dwyer. - Brian Murphy

Martin Ewen (on stilts) and Peter Henneveld, busking outside the AMP building on Queen St. - Brian Murphy

Terry Moore of The Chills at the Windsor Castle. - Brian Murphy

Chris Matthews of the Headless Chickens. “It seems I spent a lot of time taking pictures of Chris Matthews and trying to make him look like Nick Cave.” - Brian Murphy

This Kind of Punishment at The Nitpickers Picnic. - Brian Murphy

Stalker stilt theatre at their own show, His Majesty’s Theatre. Musicians are, from left: Robert Key (obscured), Bevan Sweeney, Rex Visible. - Brian Murphy

Bevan Sweeney takes a stencilled Not Really Anything poster to dry during a home print session. - Brian Murphy

Robert Key, Rachael King and Graeme Jefferies, from a photoshoot for The Cakekitchen. - Brian Murphy

Celia Mancini and friends. - Brian Murphy

The first Headless Chickens lineup. - Brian Murphy

Kevin Hawkins, Fishschool. - Brian Murphy

Shayne Carter with Straitjacket Fits. - Brian Murphy

Performers, Vulcan Lane. - Brian Murphy