“They were anti-establishment heroes, you know? That’s what I liked most about them,” he recalls. “I had blonde hair for a while – my sister talked me into putting peroxide into it. It turned orange.”

Grant was good – good enough to skate with the likes of teenage prodigy Sean Kerrigan. But as Skatopia failed and the skate boom faded, a new cultural movement caught his attention: punk rock, with its promise of not only listening to music, but picking up an instrument and playing it.

In true punk style, he didn’t wait until he knew how to play to join a band, and became the keyboard player in The Pleasure Boys.

“I bought a Yamaha CS-15 synth and just played one-note keyboard lines. Like Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark – a little bit of vibrato and oscillation, really simple. I really enjoyed it – and I still do enjoy playing simple piano lines.”

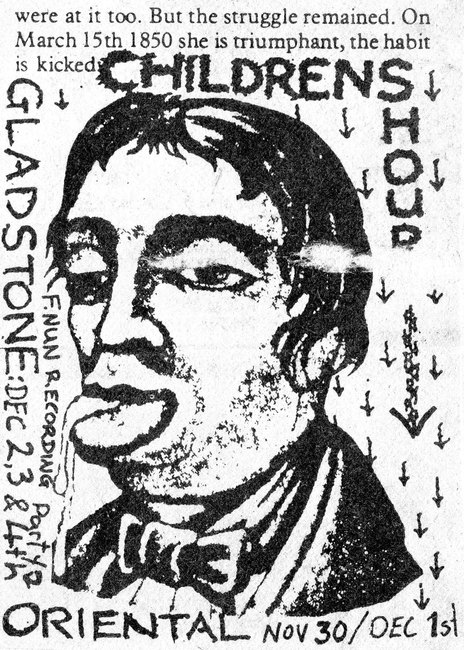

The Pleasure Boys “hung out, got drunk” and played gigs for two or three years. Towards the end, Grant met a kid from Northland called Johnny Pierce.

“I met Johnny through my girlfriend’s stepsister. And that was the beginning of Children’s Hour. We started rehearsing in his basement in Mission Bay and Chris Matthews came along. We were making songs with a little two-track recorder and Chris really liked them.”

A musical community began to form. Pierce introduced Grant to his future wife Rachael Churchward and her sister Joanna, and Matthews introduced him to Nocturnal Projections, who had relocated from Taranaki to Auckland. “I started going to see them and thinking, this good. We all became friends.”

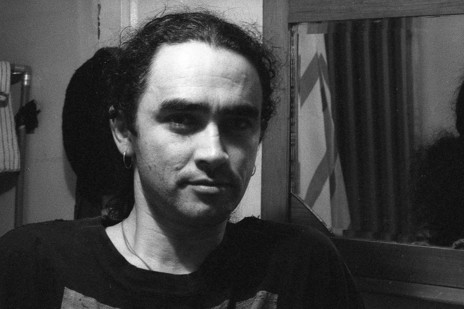

It was decided that Children’s Hour would be better served with Grant on guitar. So, just as he had with the keyboard, “I just bought a guitar and started doing it. My little guitar lines were sort of like my synth lines – dingdingdingding. Very, very simple.”

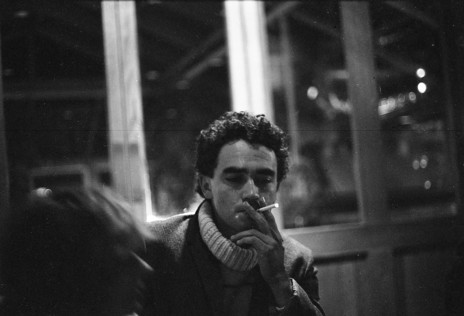

He moved into an infamous house on Grafton Road, a sprawling place with a dozen or more bedrooms, a reputation for wild parties – as I discovered in 1983 when I interviewed Children’s Hour for Rip It Up and found myself a flatmate there by the end of the evening.

“That was a pretty amazing house. That practice room out the back, which is where Chris Knox shot the video for ‘Caroline’s Dream’. We’d play in there and possums would fall down out of the ceiling and land on people.”

The video shoot was a turning point.

“I started to think about film. Chris Knox showed us the way like he always did. He was like, anybody can do this stuff. He made me feel like I could do it. Same thing again, I went and bought a camera and started doing it.”

From 1984, Grant was making experimental films with his friend Brian Wills. Like others in the scene at the time, he had the help of a benefactor at TVNZ.

“There was a guy at TVNZ who used to give away short ends and then develop them as well. We’d go around the back of the old studios and knock on the door and say ‘Hey mate, can you give us some short ends please?’ And he’d say sure and come out with a couple of cans. Then we’d take them back in and he’d process them.”

In 1985, Children’s Hour reached the end of the road and Grant and Rachael Churchward headed for Australia. Although life in Melbourne had its moments – Grant would often win money in pub pool contests and he had a “job” making up tinnies for a weed dealer – they didn’t like it and it didn’t last. In 1986, they returned to Auckland for a friend’s wedding.

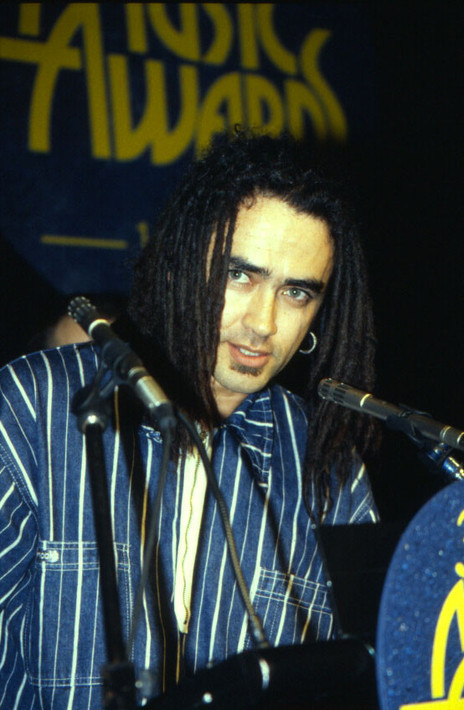

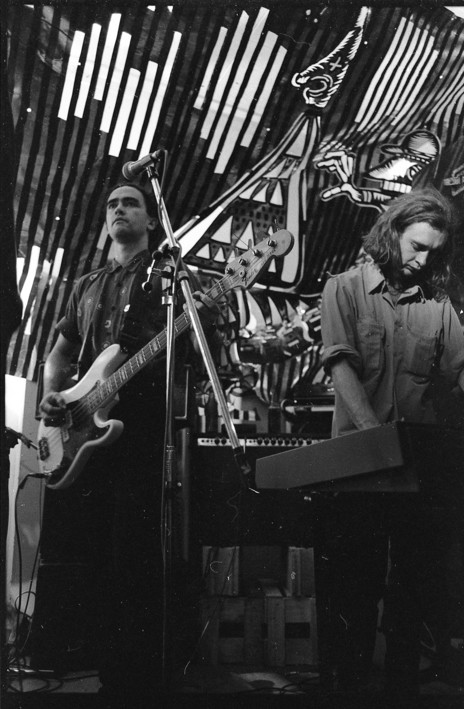

Grant settled back in Auckland to find that most of what had been Children’s Hour was now Headless Chickens. They’d substituted the dark roar of the old band for a more artistic path and, with Pierce once again the leader, rented what had been the premises of a charm school in the old His Majesty’s Arcade as their office. It was a palpably more ambitious and mature project – and it didn’t involve Grant.

“Headless Chickens had just got underway and I was like, oh, man, I like this. How come I’m not involved? I felt really left out.”

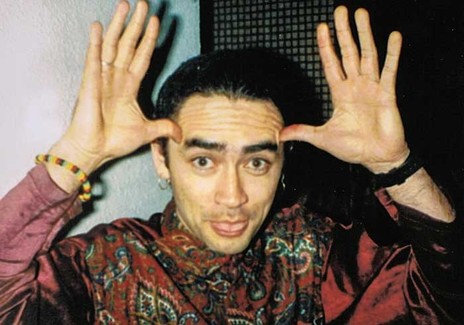

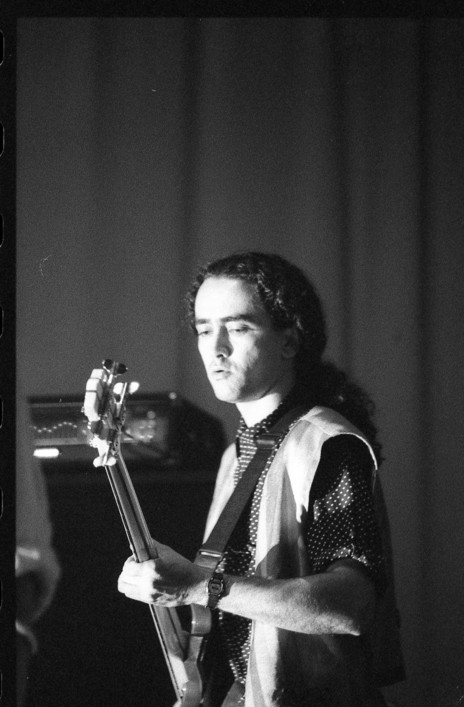

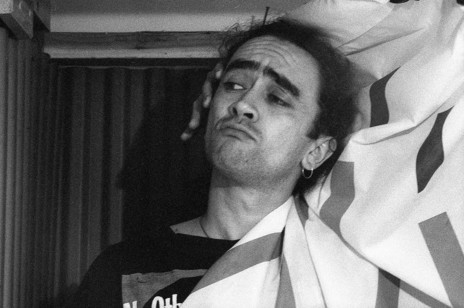

Grant’s chance to be involved came in the cruellest of ways, when Pierce took his own life. He literally took up his old friend’s instrument.

“I’d always wanted to play bass, always. And Johnny’s bass was there, the actual instrument. His mum really liked me, whereas most of the other guys she blamed for his death. When it came to it, she made sure I got the bass.”

Grant also took up another of Pierce’s roles: that of de facto manager. Pierce had always been the “Minister of Finance” in Children’s Hour, and Grant a relatively passive character. That all changed.

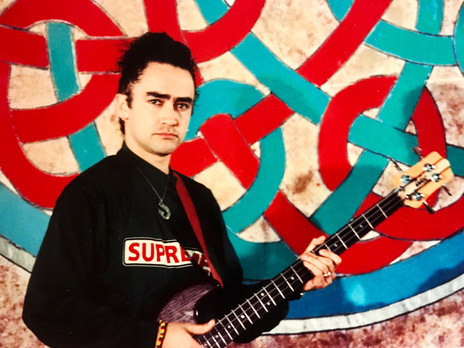

While Matthews continued to set the creative direction, as he had in their old band (“Which was how it should have been – he was the senior member of the band. Even though he was a little guy”), Fell took command of its practical elements.

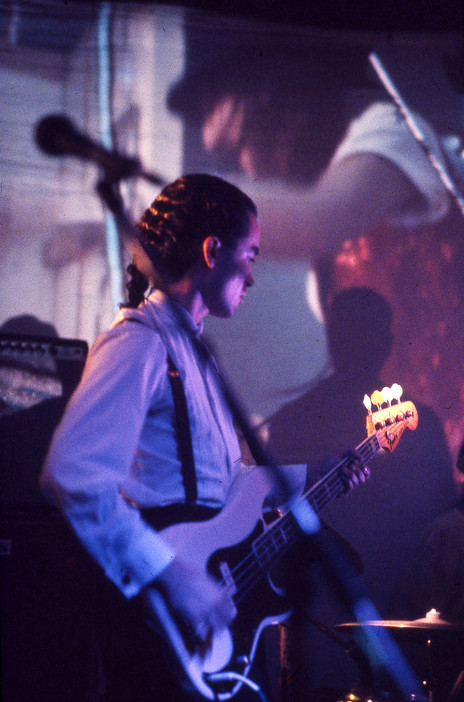

“I knew that I was quite good at managing stuff. We started shooting videos and it made sense that I could manage the band more than anyone else could.”

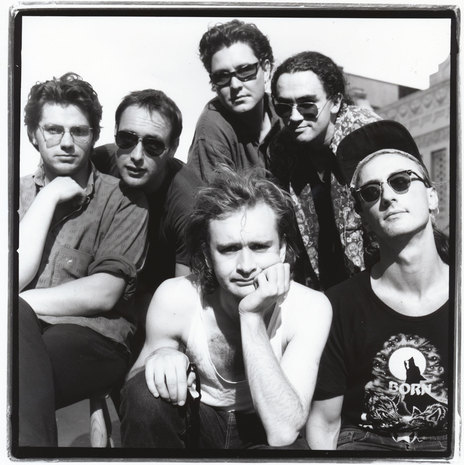

That management ability expanded across new territory for all of them: a series of multimedia stage shows at the Maidment Theatre, beginning with the Nitpickers’ Picnic. Grant and Brian Wills contributed film, another of Grant’s friends, Steven Bradshaw of Te Kanikani o te Rangatahi, brought dancers, and Children’s Hour and Headless Chickens drummer Bevan Sweeney came in with Stalker, the stilt theatre group he’d help form as part of a summer employment scheme. The Headless Chickens weren’t just a band playing a gig, but the centre of an artistic community.

“It was coming out of what we were doing [with the band],” Grant says. “There was a multimedia thing happening. We could do all this stuff together. Michael Lawry and Chris were doing stuff with technology that was groundbreaking. We were all in that groundbreaking area.”

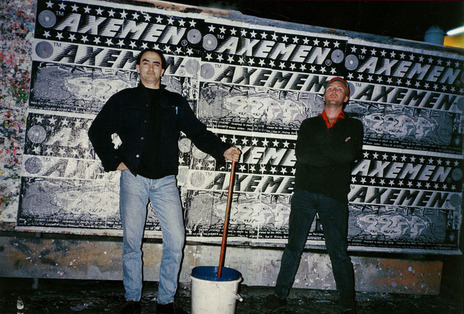

The next big event in the band’s life should have been a triumph but ended up a wearying challenge. Grant entered Headless Chickens in the Rheineck Rock Awards – and a judging panel including Doug Hood, Jude Anaru and Karyn Hay named the winners of a prize that included funding to record and market an album. There was a backlash, largely from commercial radio broadcasters who felt the band wasn’t commercial enough to justify the award.

“I couldn’t understand it,” says Grant. “We just wanted to do our creative stuff and be the best we could.”

He admits the strife became a motivation: “We did want to show those people.”

The recording process was also longer and more difficult (and expensive) than they’d anticipated, but the band’s debut album, Stunt Clown, was released in 1988 and, again, Grant was the centre of a multimedia community.

He directed the video for ‘Gaskrankinstation’, starring the band’s friend Peter Tait as the frustrated protagonist in Matthews’s song, and it went on to win video of the year at the Flying Fish Awards. The two camera operators, Kirsten Smith and Stuart Page, came from the community of friends around the band.

The song also entered the Triple J Hot 100, the first sign of an Australian following cultivated with a series of tours across the Tasman. “We worked with Wendy Boyes-Hunter. She was a good manager, so we had good tours.”

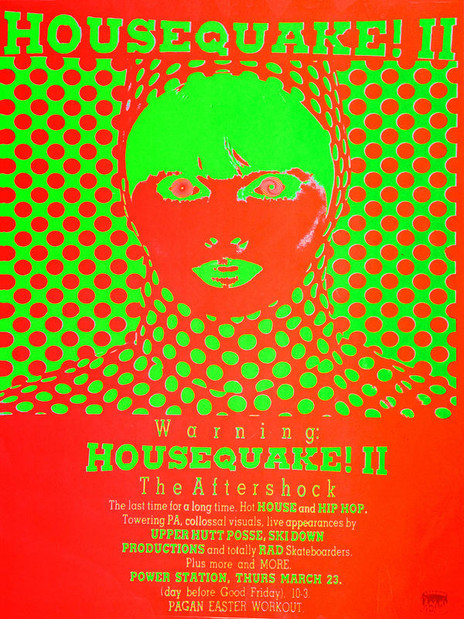

Amid it all, a new front opened up. At the end of 1988, I returned from London with a headful of excitement about acid house. Keen to stage a party, I turned to Fell, who again reeled in skilled friends. We staged two parties at the Power Station under the Housequake! banner, and more than 1200 ravers enjoyed the new music from London, an appearance by Upper Hutt Posse, skateboarding demos and a light show that included a cross built from old TV sets. The last was the handiwork of Justin Jordan, an old friend (and occasional employer) of the band, whose family made timber water tanks.

“Justin liked to build things. It was real number eight wire stuff – let’s build a TV cross.”

I went back to London, but Fell had the party bug. As 1989 went on, he staged some smaller dance parties, including Raise the Roof and Hit the Floor, at the Siren and the Box respectively. And then, as the year drew to a close, Fell convened most of Auckland’s dance party promoters for Unity, on New Year’s Eve 1989 at Auckland railway station.

“It was total mayhem. I really proud of that one. We pulled off a major event – 2500 people turned up.” From a film production company they borrowed two big foam heads and put them either side of the main stage.

Not everything in clubland went smoothly. Indeed, in 1990 Grant got involved in Surge, a club on Fort Street, that turned out to be a very rough ride.

“That was not so much a nightclub as a nightmare. It was run by the Headhunters and they were pretty heavy. My business partner Jason Miller had promised them a certain number of people through every night – and it wasn’t really working and they were putting pressure on to hurry up and get more people to spend money at the bar.

“There was a lot of pressure. I remember clearly one of them saying to Jason ‘if you don’t pick up the numbers, it’s concrete boots mate’. He had to take off and go to Malaysia or somewhere.”

In other situations, Grant’s charm served him well – never more than the time he met Michael Gudinski, the founder of Australia’s Mushroom Records, which had bought into Flying Nun Records.

“I liked him a lot. He was straight-up. When I first met him at Cause Celebre, I walked up to him and said are you Michael Gudinski? And he said, yep. And I said we need to get a better thing going with Flying Nun. Could we have a chat?

“So we went and sat down in the corner – and Michael Hutchence came over. And he said he and Kylie were big fans and they really liked that ‘Expecting to Fly’ song.”

After that night, Grant remained a favourite of Gudinski’s and the relationship would be key to the fortunes of the Headless Chickens’ next album, Body Blow.

As the recording of Body Blow wound up, the art fired up again. Jac Dwyer, who had made the model that was photographed for the cover of Stunt Clown, created the memorable backdrop for the first video for ‘Cruise Control’. The clip was directed by Rachael Churchward and photographer Bruce Sheridan. Sheridan, along with Kerry Brown, represented a new group who had come into Grant’s circle of friends – one that would become important to his next project.

“Don’t be boring, get a job and live in the suburbs,” Grant wrote to me in early 1991 as my partner and I prepared to return home from London. “Get a Mac and do something interesting.”

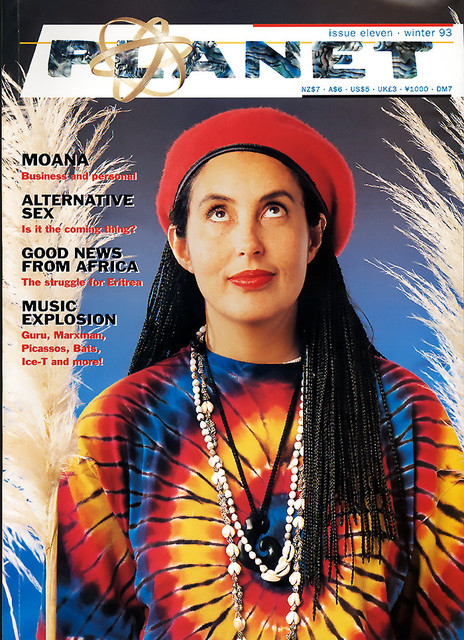

That something became evident on landing. We would, he proposed, take up Planet magazine, a street mag that had produced four issues with four different printers and paid none of them. I had some experience with editing and plenty with writing; Grant, who would be publisher, had done nothing of the kind. He simply picked it up and started doing it, as he had the keyboard, the guitar, the bass and the film camera.

The operation ran out of Grant and Rachael’s home – a roughly-converted first floor space at 309 Karangahape Road (in 2018, the DJs at Lovebucket do their thing directly underneath the old kitchen at the back of the room). It turned out to be a special time and place. K Road in the early 1990s was where bright, brown kids from the South and West converged and mingled with palagi bohemians, making art and music and fashion. A new, urban Pacific was forming.

“I loved it,” Grant recalls. “I remember about 2005 seeing the first Nesian Mystik video and thinking oh my god, this is it. We started this.”

The first issue of Planet under the new team featured Kerry Brown’s luminous photograph of a young Teremoana Rapley and the magazine, from its fashion shoots to its street polaroids, was full of brown faces.

“We were sick and tired of every magazine having a white person on it,” Grant told the Sunday Star Times in 2015. “The only brown person you ever saw on a magazine cover was a sportsman.”

Grant was also beginning to acknowledge and explore his own Ngāpuhi whakapapa. An identity that had had found little purchase in the wild but culturally homogenous indie band scene could flourish on the new K Road.

The office at 309 became a testament to Grant’s social reach. The stairs up from the street disgorged the likes of a young Zane Lowe and an impossibly confident schoolgirl called Gemma Gracewood. A sweet, goofy kid called Cliff Curtis was often around. The magazine featured Phil and Pauly Fuemana, and Stinky Jim’s first record reviews. Music and fashion blended at the edges.

“Rachael often says, ‘I was doing nothing and then Russell and Grant came to me and said, right you can be fashion editor of Planet magazine’,” Grant recalls. “And that set her off on that path.”

It turned out that advertisers would not only pay for placements, they’d pay for the ads to be produced. Grant stacked them with his musical mates. One memorable double-page ad for Airwalk shoes featured members of Upper Hutt Posse, Headless Chickens and NRA. Another, for the restaurant Guadalupe, was modelled on The Last Supper, with musicians, DJs and artists as the apostles.

At the same time, the Planet office was also the office of the Headless Chickens. As the band entered its biggest, busiest years, Grant was juggling two businesses where there was never quite enough money for what needed doing.

“I was quite stressed,” he admits. “I used to work out a lot at the gym, which kept me sane. I did kind of lose it a bit.”

Body Blow was released, then re-released. There were tours of New Zealand and Australia. And there were giant projects like the video for ‘Donde Esta La Pollo’, for which a circus tent was erected in Victoria Park. Rachael sketched out 100 characters, who were then visualised by Chad Taylor. By the night Rachael and Bruce Sheridan came to direct the shoot, there were 150 people on site. And a lot of favours had been called in.

“We got lots of help,” Grant says. “Everyone wanted to work on a creative project. That didn’t last long.”

But the strain was showing. Planet’s financial performance never matched its cultural chops. And what should have been a big new step up for the band – dates in Europe – turned out to be the beginning of the end. When they got back, singer Fiona McDonald and keyboard player Michael Lawry announced they were leaving.

“As the band manager I was really gutted when Fiona and Michael said ‘we’re out of here’,” Grant says. “Fiona was pretty stressed by the whole situation. By that point she’d had enough of being in a band and wanted to go solo. She had big plans. It was pretty challenging at the time, because we’d just come back from Europe and we had a number one single – the only one in Flying Nun history. We played to 1500 people at the Powerstation and it was just going off.”

A young Boh Runga had just landed in Auckland and Grant was keen to audition her as Fiona’s replacement.

“But Chris said no, he’d had enough of women in the band. She would have been really good.”

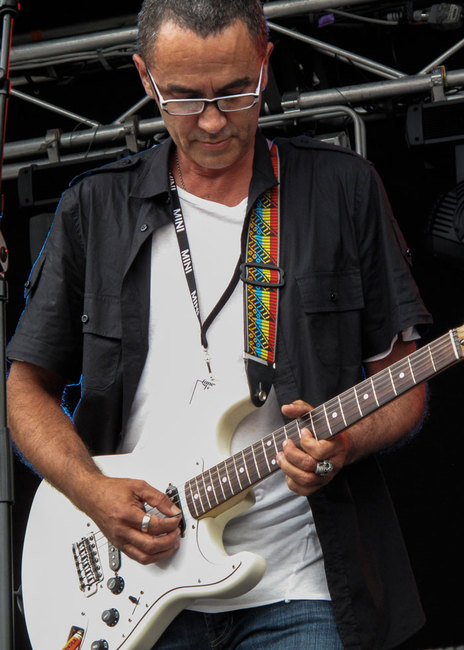

Eventually, having played on part of what would be the Chickens’ final album, 1997’s Greedy, Grant departed. He still looks on the album fondly.

“I’ve always loved ‘Smokin’ Big Ted’ and the way my bass sounded on it. It was a dirty-arsed piece of rock ‘n’ roll.”

His next venture was Octane, an events and production company he started with one of Planet’s designers, Marcus Ringrose. They won a pitch for a Sony roadshow and filled it with costumes designed by Rachael and made up by Rothmana Jordan, another old friend and collaborator.

“We put models with cameras on the catwalk. It was like an early selfie thing.”

Grant's musical focus settled on clubland. It was the heyday of Calibre and he and Rachael were the scene’s royal couple. He played records on George FM through until 2007.

Finances remained tricky in a disrupted media world and in 2008 – the year the Headless Chickens reformed for a series of Big Day Out shows – Octane was wound up, along with Grant and Rachael’s company, Black Light Publishing. Grant, so often the one to carry the can, was bankrupted. But Black, the fashion magazine they were publishing, survived under their joint editorship to earn the respect not only of the local fashion business, but the likes of the International Trade Centre’s Ethical Fashion Initiative.

They had just returned from a 2015 photoshoot for the initiative in Burkina Faso when Grant began suffering puzzling symptoms. He presented at ED worried he might have a tropical disease, but the news was worse than that. He was diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, a particularly aggressive form of brain cancer.

A life of forming communities paid back, as old friends and both music and fashion figures contributed tens of thousands of dollars towards Grant's treatment and support. But, after positive medical news in 2017, his health deteriorated sharply. He passed away on January 27, 2018.

Grant Fell will be remembered as the guy who knew everyone, the guy who felt everything could be done if you just started doing it and anchor that communities formed around. Perhaps it was appropriate that he spent most of his time in bands as the bass player. Just as his job on stage was to keep the groove going, so it was out in the world.

--

Unless otherwise noted, quotes from Grant Fell in this article come from an interview conducted in 2017.