I railed against sexism and scorned boys in bands with their loud guitars – dismissing them as boring and counter-revolutionary poseurs. I went to gigs – The Slits, The Raincoats, The Mo-dettes, Gang of Four, The Pop Group.

Everyone I met was at art college or trying to be an actor or a writer or a filmmaker. Everyone was experimental and everyone was in a band. Punk spat at the idea that you had to be “musical” to make music. All you needed was an instrument or a voice and a lot of attitude. A band was not so much about the music but more a statement of intent. It was a vehicle for ideas.

I started my first band with a punk girl who lived across the street. Her name was Traci and we called ourselves The Unfuckables. She played bass and I played a beaten-up old saxophone that, if I bit the reed in just the right way and blew as long and as hard as I could, I could make scream and rant with a shockingly loud fury. It was the sort of (anti-) music that girls weren’t supposed to make.

We used to play together just for fun in the front room of my squat, but then someone got us a gig at an anti-psychiatry conference in Red Lion Square. Instead of being grateful for the offer of a gig, we were rather affronted that we would be perceived to be a “proper” band. In order to dispel this idea, we put the word out around the neighbourhood and 30 people turned up for a night of mad improvisation which went down as the one-and-only, legendary Unfuckables gig.

“I HAD A GREAT TIME INCITING SMALL RIOTS AND PLAYING ANARCHIC PERCUSSION.”

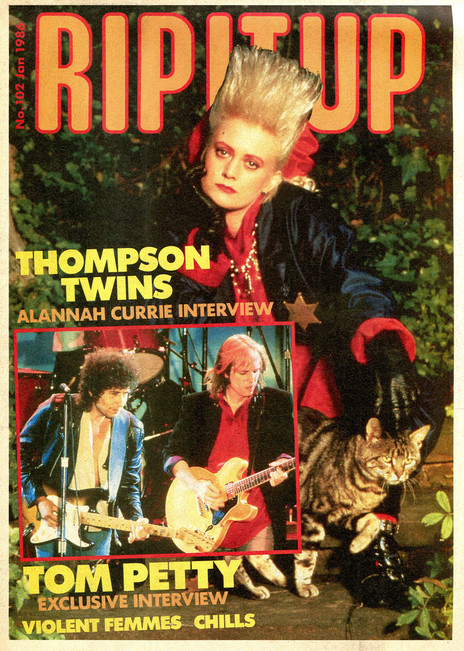

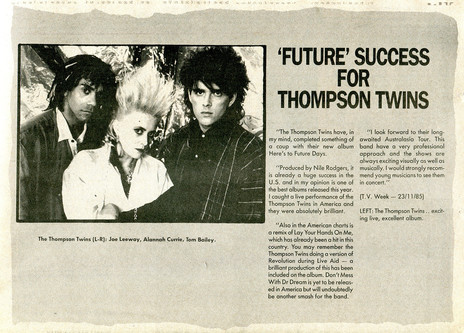

Around that time a group of boys from Sheffield moved into a squat across the street. They had a four-piece band called the Thompson Twins and invited us to come and play with them and spread the Unfuckables’ chaos around their gigs. Traci thought it was a sell-out but I said yes and went on my own, just curious to see what would happen.

I ended up going on a couple of tours around the UK with them, and had a great time inciting small riots and playing anarchic percussion. Every gig was exciting and unpredictable and I loved the connection that I got through performance.

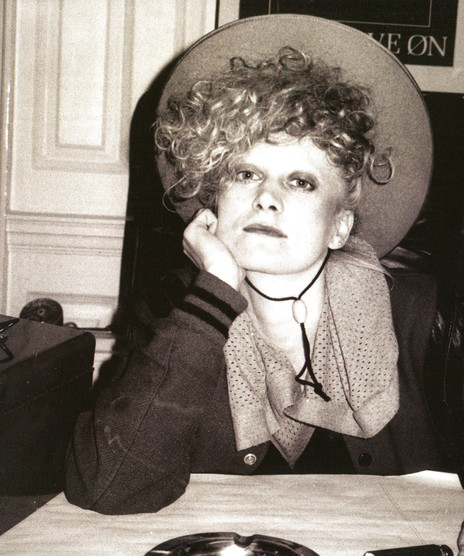

Being the only girl in a band with six boys was hard work, especially as I was essentially playing the part of a chorus girl – albeit a very angry and slightly wild one. To prove my worth I helped rig the PA and learnt how to operate the mixing desk, despite having no interest whatsoever in any of it. I hated the way that when I went on stage you’d get the inevitable “get your tits out” stuff from the blokes in the front row. I started wearing big hats and boots and played really loud just as a way of protecting myself and diverting male attention away from my body.

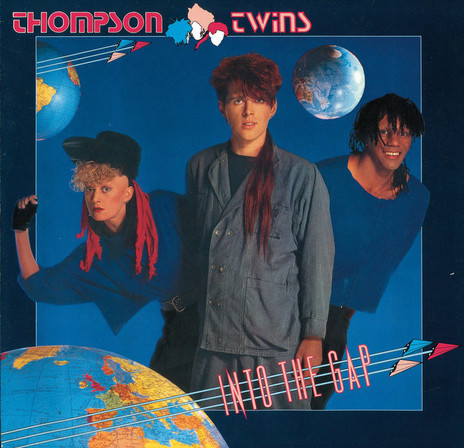

When that band imploded, I formed the new version of the Thompson Twins with Tom Bailey and Joe Leeway. We created a manifesto that gave each of us equal rights and equal responsibilities within the band. MTV had just begun and video was emerging as a powerful new addition to music tracks. I took the job of creating the videos and the image of the band, as well as writing lyrics and being mistress of all things percussive.

I was determined not to be seen as some girly decoration but to use it as a playground for my own ideas. I deliberately created an image of androgyny for all three of us – the boys wore make-up, I wore trousers and an oversized engineer’s hat, and all guitar solos were banned until further notice. I played drums, and built and played odd machines incorporating hammers and fire extinguishers in order to present myself as a brave on a new frontier.

I borrowed all sorts of imagery for myself and mixed it up ... Russian constructivism ... Bette Davis ... cowgirls ... surrealism. My greatest influence was not musical but that of the English eccentric poet Edith Sitwell. I loved her play with words and rhythm, and admired her strange birdlike dress. She was one of several great women I identified as having an intelligence and uniqueness that set them apart from the mainstream. They were equal to men and did not compete with each other.

The first record we made as the three-piece Thompson Twins was brilliant. We flew to the Bahamas to record with Grace Jones’s producer Alex Sadkin. He understood what we were trying to do and encouraged us in every mad idea we had. We used drum machines and synthesizers, which at the time were not considered “proper” instruments, especially in America. I played with Iyrics – surreal and ironic – and made percussion loops from anything that came to hand. Mistakes and discordant sounds were treasured and made for great innovation.

“THAT FIRST RECORD WAS A HIT ... BUT IT ALSO MARKED THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF THE GREAT ANARCHIC ADVENTURE.”

Sly and Robbie would wander into the studio and mess around with our drum machine. Grace Jones’s mum played bad church tambourine, and Grace even deigned to sing opera on one of our tracks in exchange for our vocals on her track.

Despite its counterculture facade, the music business is a multinational industry. Making money is their top priority. In the 1980s they were particularly reactionary and unimaginative when it came to the way they portrayed and marketed women. Unless you had management to fight your corner it was hard to stay edgy and keep true to your own vision. It was often pointed out to me that we could sell a lot more records if I would “be more sexy” and “drop the feminist stuff”. That first record was a hit in both the UK pop charts and in the US dance charts, but it also marked the beginning of the end of the great anarchic adventure. As soon as we started selling a lot of records, we rapidly went from being an experimental art-synth band to a commodity. We had signed to a major label and were hopelessly naive in thinking we could be anything other than slightly subversive.

For a long time, I stood my ground and contemptuously constructed bigger hats while insisting on employing women wherever we could. It was hard work being consistently defiant, and deeply disappointing that my value in the band was primarily down to how I looked, and that my work as a lyricist and rhythm maker was of no real importance.

By the time we made our third album, my anti-music approach was no longer considered to be a useful tool in the studio and I felt redundant to the record-making process. This was reinforced when in later recording sessions it was suggested we get in “professional musicians” to play the parts I had written.

Disheartened, I withdrew more and more, leaving most of the playing up to the boys. In order to hide the huge sense of betrayal I felt, I claimed loudly “I was only in it for the clothes anyway.”

“THERE ARE PROFOUND MOMENTS OF CONNECTION IN BOTH WRITING AND PERFORMING.”

It wasn’t until much later, when the pressure of making pop records was over and we had our own studio, that I started making records again. I discovered my own voice as an artist, but never felt that excitement of making those first records again.

There are profound moments of connection in both writing and performing that transcend the confines of gender. Nothing compares to those moments of incredulous joy that you sometimes get when you are performing or when you marry a rhythm with a word or a melody with a voice and everything just flies. It’s like fucking god for a nano second, and it’s what keeps you going back for more even when you know in your heart the party is over.

The last record I made was Into the Ether with Babble in 1994. It was a strange and disconnected piece of work, reflecting how I felt at the time. It was dark and evocative but failed dismally as a vehicle for more complex ideas. I had gone as far as I could go with pop music. My accidental love affair was over.

--

From Kiwi Rock Chicks: Pop Stars and Trailblazers, edited by Ian Chapman (HarperCollins, Auckland, 2010). Republished with permission.