AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

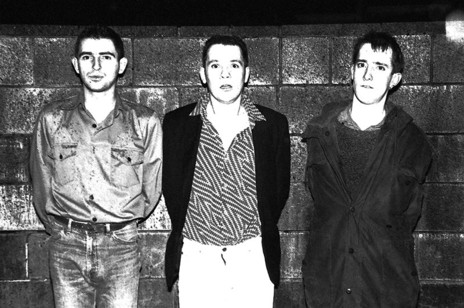

Pretty Wicked Head & The Desperate Men

Theirs is a story of tenacity, brave endeavour, late nights, fist fights, fast food, cheap booze and, ultimately, missed opportunities. It’s a quintessential Kiwi rock and roll tale, minus the 15 minutes of fame.

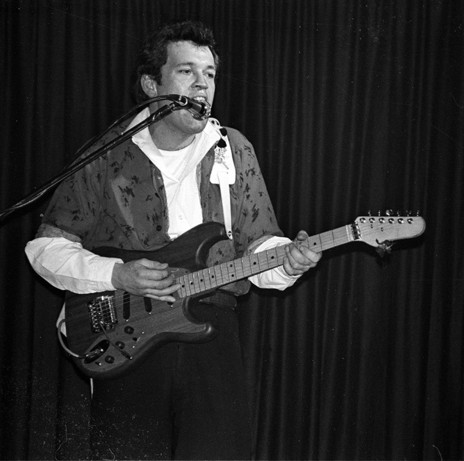

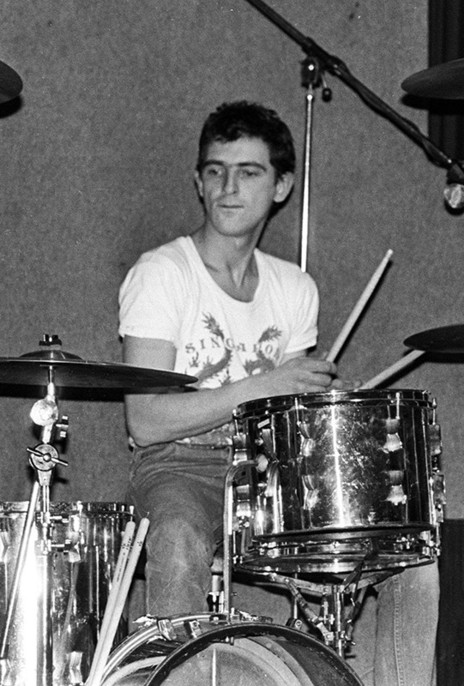

The gritty trio actually started as a duo in early 1986, combining the talents of drummer Vaughan Burtenshaw and singer-songwriter and guitarist Shaun Kirkpatrick.

Kirkpatrick spent his formative years rising through the ranks of Invercargill’s alternative elite, in a string of impossibly cool bands with artful names like the Ya-Yas, Romeo and the Daneceabouts , the Jesuit’s Birthday and then Bander and the Answering Ball.

Burtenshaw had also been in two of those bands, Romeo and the Danceabouts and Bander and the Answering Ball.

Another former bandmate of Kirkpatrick’s in the Ya Yas was drummer Gary Sullivan, who later became known for his work with high-profile New Zealand bands including Jean-Paul Sartre Experience, Dimmer and The Adults.

From lyrical Irish stock, Kirkpatrick was a former amateur pugilist blessed with a solid right hook and a vicious wit. His heightened sense of the absurd was aptly reflected in his new band’s name. His intensely manic stage presence made for a riveting watch, regardless of the occasion.

With roots in primal rockabilly, Kirkpatrick was equally adept at deadpanning Elvis Presley songs in a rich baritone voice as he was screaming expletive-laden lyrics over frenzied punk guitar rhythms.

The new duo quickly got attention for their loud and wild gigs.

The new duo quickly got attention for their loud and wild gigs, and their willingness to play to any audience in any venue, the Road Knights gang headquarters included. In a small city where two rival gangs were at war, playing a gig for one invited the threat of being targeted by the other.

In late-80s’ Invercargill the Damned, who were the Road Knights’ sworn enemies, had their headquarters next door to the Southland Musicians’ Club in Preston Street, in the industrial suburb of Prestonville. On at least two occasions, Damned members crashed Pretty Wicked Head parties at the club with retribution on their minds.

On one occasion they tipped Kirkpatrick’s van on its side in the driveway, and on another a small posse jeered and challenged Kirkpatrick and Burtenshaw as they performed inside the club, until the two musicians leapt off the stage into the middle of an all-out brawl on the dancefloor.

Pretty Wicked Head and the Desperate Men had an exciting, slightly dangerous bad-boy reputation and a growing audience, but Kirkpatrick wanted more. He cast his eyes north looking for more productive pastures and his gaze settled on Canada.

Putting Pretty Wicked Head on hold, Kirkpatrick uprooted his young family and flew to Vancouver, taking with him a raw demo tape of some of his songs.

Perhaps some of the people he encountered then had a degree of admiration for the brazen cheek of the unknown musician from New Zealand. He immersed himself in the Vancouver scene, shook countless hands and jammed with as many local musicians as he could.

He made some useful friends, entrepreneurs who encouraged him. Come back when you’ve got a band, they told him. Kirkpatrick took that advice on board.

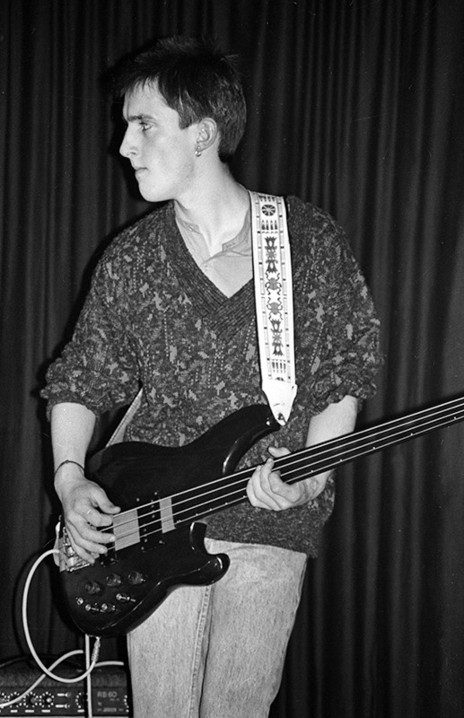

Back in Invercargill the following year, Kirkpatrick called up Burtenshaw and the pair set about finding a bass player to complete the lineup. They chose Kane Ker, a talented young artist and an innovative fretless bass guitarist.

Not only did they bring creative chops to the band, they were ideal visual foils to Kirkpatrick’s borderline manic stage persona. Burtenshaw went about his business with an exaggerated high stick action and the precision of a Swiss movement watch, and Ker was a visual cacophony of angular limbs, jerky movements and elastic facial expressions.

As a live act they had a lot going for them. The trio quickly built a hometown reputation for their edgy, confrontational live performances and Kirkpatrick’s memorable post-punk anthems.

Kirkpatrick wasn’t precious about his music. He brought his lyrics and chord progressions to the others, and invited them to add their own musicality to the mix. The three of them worked well as a creative force.

“It’s a comfortable band,” he told The Southland Times in 1988. “There’s no room for egos.”

In 1988, Invercargill had a dour social landscape. The winters were cold and bleak, the pubs shut at 11 o’clock and after that the wide streets were empty save for the seemingly endless procession of V8 cars packed full of young men doing laps of the centreplots.

In this conservative rural service town enclave, the music scene’s bright creative sparks tended to radiate around the man they all looked up to, Shaun Kirkpatrick.

Invercargill had about half a dozen original bands covering the rock spectrum.

Invercargill had about half a dozen original bands covering the rock spectrum from punk to metal, followed by a small battalion of friends and fans who tended to support each band regardless of genre.

Often the bands would play support on each other’s bills. It was not uncommon for a Saturday night at the Glengarry Tavern to feature any combination of Pretty Wicked Head and the Desperate Men, punks Moral Fibre, indie rockers London Polyplop and Isolation Backlash, hard rockers White Pussy or Bluff metallers Militia.

Pretty Wicked Head, as they were commonly known, were easily the band to beat. They were relentless and prolific, and with Kirkpatrick’s edgy, thought-provoking music they had a quality that suggested they were destined for other places.

Their sets were brim-full of exciting original songs and skilfully selected covers few in the provinces had heard of, and which arguably improved on the source material – songs such as ‘Winning’ by The Sound, ‘I Am The Fly’ by Wire, and ‘Change’ by Killing Joke.

Despite the band being in its promising infancy, Kirkpatrick was already trying to secure a national record deal. A 1988 letter from Trevor Reekie at Pagan Records gave brutally honest feedback.

“Yeah, you’ve got something going,” Reekie’s handwritten letter says. But “I’ve got a financial problem that makes Sinatra sound like Anthrax” and “it does preclude me from doing anything with new artists for ’88 ... The only way you’ll know is to get out of Invercargill & work your arses off in C/ch/Well/Hamilton/Ak.” [sic]

That’s what the band did, touring and playing relentlessly up and down the country, surviving from gig to gig.

By early 1989, Pretty Wicked Head and the Desperate Men had nowhere left to go in New Zealand. The time was right to return to Canada.

Razor sharp from months of playing, Pretty Wicked Head flew to Canada for a three-month musical adventure that took them cross-country from Winnipeg to Vancouver.

Their frenetic live performances and enthusiasm quickly earned them attention. In April 1989 they secured a gig at the prime Vancouver venue Town Pump, which coincidentally was filmed by a group of trainee camera operators and broadcast on a local TV station.

On advice they signed up as members of CAPAC, the Composers, Authors and Publishers Association of Canada, which enabled them to apply for funding to record a better-quality demo tape than the one they’d brought with them from New Zealand.

They got enough money for a day’s worth of recording at Vancouver Studios and quickly put seven songs in the can, mostly in one or two takes as time was against them. The tracks were tight and bristled with energy.

On June 9 they played support for Public Image Ltd at The Commodore venue in Vancouver. After the show, Vaughan Burtenshaw brushed shoulders backstage with punk royalty when he passed John Lydon in a corridor. “Great gig, man,” Burtenshaw offered in a solemn gesture of musical solidarity. “Do you mind?” Lydon sneered back at him.

While in Vancouver, Kirkpatrick found a useful ally in Laurie Mercer, an agent from S L Feldman and Associates.

A fan and good friend of the band, Mercer offered contractual advice and after PWH had returned to New Zealand he gamely set about trying to secure them a North American deal, armed only with a single cassette of some of the Vancouver Studios demos.

“I have played the tape for a number of record company people, and they have been mildly positive about it,” he faxed Kirkpatrick on 31 May 1990, but “it is hard to sell songs without a band”.

Back in New Zealand, Pretty Wicked Head threw themselves into another punishing regime of touring, earning some positive reviews along the way. “They affect the feet as much as the brain with their offbeat rhythms and topical lyrics,” wrote John Greenfield in the Christchurch Star, in November 1989.

In a bid to protect the band’s intellectual property, Kirkpatrick formed his own company, Oreti Records.

With seven tracks already recorded in Vancouver, the band now had an album’s worth of material on tape.

In July 1990 PWH borrowed a friend’s Transit van and drove from Invercargill to Wellington to record four more tracks at Marmalade Studios, with Tim Farrant at the mixing desk.

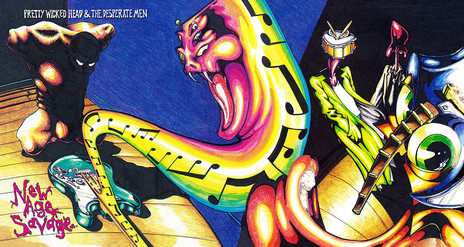

With seven tracks already recorded in Vancouver, the band now had an album’s worth of material on tape. The album would be called New Age Savage, and Kirkpatrick started shopping it around the New Zealand record companies.

Only Jayrem showed any interest, offering Pretty Wicked Head a distribution contract, but Mercer looked over it and faxed Kirkpatrick from Canada advising him not to sign it.

Instead, Kirkpatrick rounded up the money from friends, family and supporters to release New Age Savage independently, on cassette. Five hundred copies were made, each one of them stamped on the inner cover with Kirkpatrick’s then home address and phone number.

The striking, eerie surrealist artwork used on the cover was created by a friend of the band, Pablo Kelly, using felt pens.

Yet again, the band members threw themselves headlong into touring New Zealand, garnering some attention and good reviews along the way.

In August 1990, Grant McDonagh wrote in the Sunday Star: “While all the trend junkies were off being ‘more-depressed-than-thou’ at a pay-at-the-door Goth party, about 50 punters, myself included, had a great time enjoying some REAL rock ’n’ roll from Invercargill ... Pretty Wicked Head and the Desperate Men think for themselves and enjoy audiences that are receptive if not that huge.”

Kirkpatrick was acutely aware of the pitfalls of over-exposure in his hometown, telling the Southland Times they could only play in Invercargill once a month.

The band played hard, partied harder and travelled far and wide, working the national pub circuit in short bursts from Stewart Island to Auckland, all the time honing their ever-sharpening stage act.

Kirkpatrick was relentless, continuing to shop the band around New Zealand record companies, big and small. When they approached Trevor Reekie of Pagan Records again, he responded with a similarly forthright response to that of 1988, although this time his rejection letter was typewritten.

“I’m sorry that Pagan has to pass on this project,” Reekie wrote, “but we’re the smallest indie in the country and we really are stretched keeping up with the present roster of artists … The material is shit loads better than most of the drivel I get sent but I feel it would also be too much for Pagan to handle trying to break this band.”

He suggested Kirkpatrick try CBS and EMI. Kirkpatrick tried them both. Both passed.

It wasn’t all negative, though. Rip It Up magazine named New Age Savage as one of the best releases of 1990, and reviewers were enthusiastic as Pretty Wicked Head kept up their relentless touring schedule.

The constants gigging helped the band to sell cassettes and, with stocks running low, Kirkpatrick launched a desperate campaign to attract major record company backing and a distribution deal.

Eventually, in late 1990, after yet another flurry of faxes to industry bigwigs, Kirkpatrick finally got somebody’s attention: Morrie Smith, BMG’s New Zealand managing director. Negotiations began in earnest.

Meanwhile, Kirkpatrick contacted the Vancouver of office of SOCAN (the Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada, formerly CAPAC), to find out how it would collect royalties on the band’s behalf from the other side of the world. SOCAN advised him to sign Oreti Records up as a member of APRA as soon as possible, to maximise any royalty payments.

Canada still figured prominently in Kirkpatrick’s plans. In November 1990 he faxed Laurie Mercer in Vancouver and laid it all out with typical forthright honesty. “I personally feel we are ripe for the picking and somewhat stifled in New Zealand with its small population and lack of adequate venues, and we are rearing for an opportunity to prove ourselves.”

What were the chances of Pretty Wicked Head returning “to your wonderful part of the world” for more recording and touring, he asked.

In a significant change in late 1991, the Pretty Wicked Head trio became a quartet when they added their artist mate, Pablo Kelly, as a second guitarist.

Soon after, on 3 February 1992, Kirkpatrick signed a five-year global manufacturing and marketing contract between Oreti Records and BMG Arista/Ariola (NZ) Ltd.

The deal was that initially BMG would release and distributed a single (‘All New Zealand Heroes’ b/w ‘Let’s Go Slow’), a five-track cassette and a compact disc of New Age Savage.

“This fax efficiency is the ultimate godsend to bands who want to tour abroad,” said Kirkpatrick in 1992.

Kirkpatrick told the Southland Times being based in Invercargill was unlikely to be a disadvantage. “This fax efficiency is the ultimate godsend to bands who want to tour abroad,” he said.

In March 1992 the band were making plans to independently film a music video for All New Zealand Heroes, to be filmed by Pablo Kelly’s dad, Pat Kelly. It was played once on Television New Zealand before being pulled and was never seen again publicly. Finding a copy on VHS videotape has become the holy grail for fans of the band.

“The video had about a dozen broadcasting breaches, apparently,” Pablo Kelly said. “Shaun sticking a knife in a toaster, bare bums, even a man wearing a bra was inappropriate at the time. I remember thinking the ruling was pretty ridiculous given the raunchiness of American pop videos playing on Saturday morning TV.”

Momentum was quickly lost as BMG Arista lost interest in their unruly, uncommercial signing and within the Pretty Wicked Head camp disillusionment was starting to set in.

The band eventually returned to Canada, playing two prime showcase sets at the prestigious Music West Festival in Vancouver in 1993.

Some tentative inquiries, including from the UK, followed, but it seemed Pretty Wicked Head’s moment had passed before it happened. Eventually, weary from the years of slog, Kirkpatrick stopped chasing gigs and although the band never officially broke up it ceased to be a going concern.

Kane Ker’s tragic death in 2005 was the official full stop to one of the most colourful chapters in Southland rock’n’roll history. Pretty Wicked Head and the Desperate Men were gone but not forgotten.

In 2011 a small group of fans raised the money to re-release a remastered, repackaged edition of New Age Savage, including a DVD of the band’s 1989 set at Town Pump in Vancouver.

Pretty Wicked Head’s impact on what was then a burgeoning Southland original music scene cannot be underestimated. They blazed a fearless, albeit bumpy, trail for other young original bands to follow and at the time of writing they remained the only Southland band to be signed with an international label while still based in Invercargill.

In 2017 Kirkpatrick and Burtenshaw received warm accolades from their peers when they reunited to play a set at the Southland Entertainment Awards, where they were presented with a Lifetime Legacy Award. In 2018 Shaun Kirkpatrick was still writing songs and occasionally performing them with his good mate Vaughan Burtenshaw.

Oreti Records

BMG Arista/Ariola (NZ) Ltd

Shaun Kirkpatrick - vocals, guitar

Vaughan Burtenshaw - drums, vocals

Kane Ker - bass, vocals

Pablo Kelly - guitar, vocals

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air