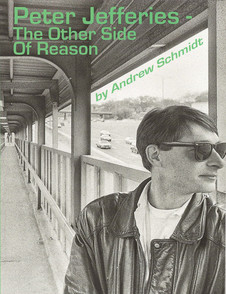

An excerpt from Peter Jefferies – The Other Side of Reason, by Andrew Schmidt (Hozac Books, Chicago, Illinois, November 2024).

Sliding down the last inland range from provincial Otago into the city of Dunedin, spread out below in the elbow of the soft hills above the harbour inlet and its southern beaches, Peter Jefferies felt the excitement and new possibilities rise in the chill late winter air of 1985. Sick of Auckland and This Kind of Punishment, the Stratford musician needed a new place to stand, and the southern indie haven looked a good bet for the near future at least.

In amongst the city’s ageing housing, gothic stone-block churches, heritage structures and greening copper spire atop the original building of New Zealand’s first university, he’d find a community well-suited to his needs and dreams. In the wake of punk, the city had taken on another identity as a post-punk musical centre and ever more powerful magnet for creative New Zealanders: especially those from the smaller centres, who found the culture shock in transferring to their new home minimal. People in Dunedin were polite and open, rent was cheap, and in amongst the tertiary students attending the country’s oldest university or hanging around the city soaking up the musical life, a strong fan base and new cultural community had developed, which included the small clutch of musicians Peter Jefferies first encountered on This Kind of Punishment’s South Island tour a bare few months before. The cultural cadre they’d soon form would kick off a fresh post-punk musical phase in the city.

Peter Jefferies in Dunedin, mid-1980s. - Peter Jefferies Collection

Peter Jefferies and his new allies would establish what became Dunedin’s first successful city-based and internationally known independent label by unfurling a darker, more emotionally and intellectually resonant sound in local live venues, and on tape and record. The varied sounds they captured in Dunedin houses, warehouse spaces and small embryonic recording studios helped establish a long-lasting international reputation and cultural footprint for the acts still discernible three decades on. And close to the centre of nearly all of the new activity would be Peter Jefferies, musician, composer, sound engineer, record masterer and all-round creative inspiration. That would come soon enough, but for now, Jefferies was taking one last holiday with girlfriend Jenny Brooks before she headed off to a new life in England.

“I liked Dunedin pretty much from the get-go,” Peter Jefferies says. “You couldn’t help but notice the energy of the place and the interaction of the people there. It felt a lot friendlier than Auckland. Jenny and I were there for months. We’d tiki-toured down the country stopping off at different places, but our eventual destination was to get to Dunedin, where we got a flat out at Caversham. Bruce Russell biked all the way out to see us when we arrived.”

Jefferies soon immersed himself in the city’s small music community meeting amongst others, Shayne Carter, the talented singer and guitarist, who’d shown great musical promise up front of Dunedin punks’ Bored Games and in Doublehappys with The Stones’ Wayne Elsey.

Elsey had died tragically in a train accident on June 26, 1985, while returning home from touring, and the sadness and abruptness of his too-young passing left the tight southern community numb. It was a malady Carter and Jefferies would soon help excise, when they worked up a musical eulogy that remained a high point in both their long creative lives.

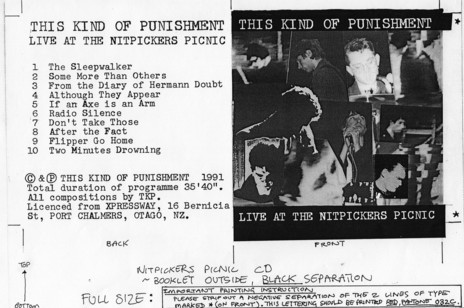

This Kind of Punishment

But before that went down there was the no-small-matter of the Johnny Pierce-organised multi-media show The Nit-Picker’s Picnic to attend to in Auckland. The ambitious artistic undertaking, due to play out over two nights on July 23 and 24, 1985, at University of Auckland’s Kenneth Maidment Theatre, drew strongly on the varied talents of the creative crowd that circled This Kind of Punishment and the now-disbanded Children’s Hour. It featured music, theatre and cultural groups, including Te Kani-Kani O Te Rangatahi, The Von Trans Sisters (Annabel Lomas, Maxine Fleming and Andrea Kellard), Chris Matthews and Johnny Pierce’s new group, Headless Chickens, satirical sketches, and the David Clarkson play, Voice, with soundtrack by Clarkson and Michael Lawry. Andrea Kellard read an excerpt from Sarah Daniels’ Masterpieces and Chris Knox acted out as Salivation Army.

“Johnny Pierce organised the whole event and he put heaps into it, people knew that, but I didn’t want to do it at first,” Peter explains. “I had to be talked into going back to Auckland. I was in Dunedin, and I wasn’t coming back for that shit. But Graeme said, ‘Look, Johnny’s put a lot into this.’ I had to go back up north anyway because my father was dying in Whakatane. I’m glad I did, because I really think they were absolutely the two best This Kind of Punishment shows. The setting was amazing, the sound was sharp, and although the live recording didn’t come out that well, the live sound on the night was good. All the acts were interesting. They didn’t upstage us, but they kept the audience engaged.”

This Kind of Punishment, Live at the Nitpickers Picnic, 1991

Nocturnal Projections drummer Gordon Rutherford recorded both This Kind of Punishment performances on his trusty TEAC 4-track. The “electric-chair intensity of these versions radically transforms the earlier material and prefigures the amped-up attack of the final TKP album,” Bruce Russell later wrote in an unpublished 1991 sleeve note for an aborted record of the event.

Returning south again, Peter Jefferies settled into the hometown of The Clean, The Verlaines, The Chills, The Stones and Sneaky Feelings. “Dunedin had the same kind of feeling as New Plymouth had from 1980 to the start of 1982 with the Nocturnals,” he explains. “It had that feeling in terms of having a fan base around you and an audience, a bunch of interested people. The difference was in Dunedin there were a whole lot of people doing great music, whereas, in New Plymouth, there wasn’t really anybody except us. There were just a few young bands, who’d just started up. There was so much good music going on around you in Dunedin it felt like being part of a musical family. And that feeling was at its height when I was there. I thought I’d never leave. Why would I?”

Jefferies became close with Shayne Carter and the two mouthy-driven musical geniuses began work on ‘Randolph’s Going Home’, a single honouring their fallen friend Wayne Elsey. “You see, I knew Wayne too,” Peter says. “We were friends and his dying really upset me. When The Stones came up to Auckland, they’d come and stay with us. Some of the first This Kind of Punishment album was recorded on borrowed Stones equipment. I don’t think we had a bass at that point, so we borrowed Jeff Batts.

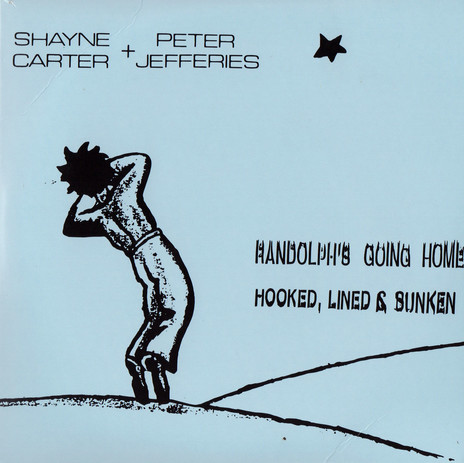

Shayne Carter and Peter Jefferies - 'Randolph's Going Home'

“Shayne and I recorded ‘Randolph’s Going Home’ in the last days of my first stay in Dunedin. Shayne and Bruce Russell were flatting together upstairs in their classic flat, up in George Street, and there was a little room out beyond there that was set up as the Doublehappys’ practice room. One of the things Shayne and I jammed in there was the tune for ‘Randolph’s Going Home’. I played it first with what I thought was typical Dunedin drumming. I don’t know why I did that. But I played it straight forward and Shayne played to it and then said, ‘That’s pretty much what [Doublehappys] John [Collie] played,’ then carried on.

“At one point in the jam, I started playing what became the drum part for ‘Randolph’s Going Home’. I was drumming a beat then changed it to another beat, and Shayne stopped and said, ‘Hold on a minute, could you play what you were just doing then?’ I’m like [does drumbeat] and he’s standing there nodding. You could tell he was trying to connect it – to work out how to fit it in. The masterstroke was when he realised how to turn the main melody into a countermelody that fitted to the beat. When he did that, we were on our way. I think that’s why Shayne gave me a writing credit. I got him to change one line of the lyrics and we played it through and, bingo, we had ‘Randolph’. I think it’s my best bit of drumming. It starts up and you know instantly what song it is before Shayne does anything. It’s hard to do that with a drum line.”

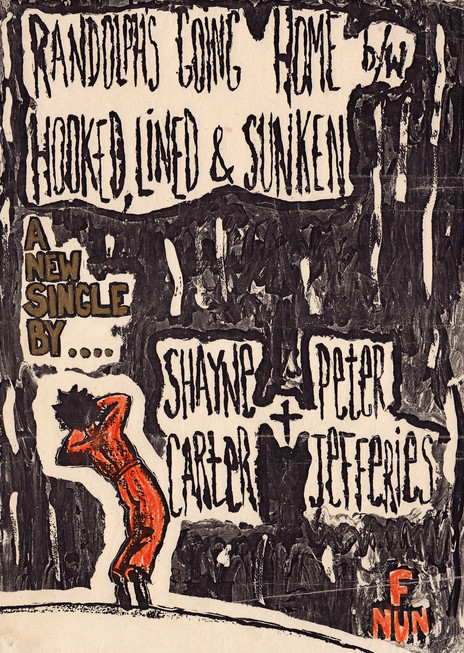

Poster for the Shayne Carter / Peter Jefferies single and tribute to the late Wayne Elsey, 'Randolph's Going Home'.

In the cavernous warehouse space of Chippendale House in Stafford Street, the punkish pair utilised the wide staircase and with help from sound man, Ivan Purvis, captured the mournful keening eulogy to Elsey and its flipside, ‘Hooked, Lined and Sunken’, between November 4 and 7, 1985. The drum beat for ‘Randolph’ proved especially hard to re-create, taking up to nine hours. But a week later, the single was done and mixed in the same venue.

“There’s a bloody great hole in ‘Randolph’ down in the low midi area,” Peter says. “When we were recording it and the song got to that point, I just expected Shayne would fill that bit in. But he was like, ‘Nah, there’s nothing there.’ I said, ‘Why not?’ He replied, ‘Because that’s the bit that Wayne would be playing.’ Like that’s his area and you can’t fill it in.”’

Turned out ‘Randolph’s Going Home’ wasn’t the only song about the much-missed musician Peter Jefferies played on. Jay Clarkson asked him to contribute piano and drums to her Elsey memorial, ‘Gone’, and piano to two other tracks, ‘A Loose End’ and ‘Penelope’, on her first solo album, released in 1986.

“Jenny and I left Dunedin the day after mixing ‘Randolph’ and I already knew I was going to go back. But her leaving brought me right down and I spent three months licking my wounds at my mother Gwen’s place in Stratford. I just felt lousy. The only songs I could listen to were ‘Randolph’s Going Home’, TKP’s version of ‘Out Of My Hands’ and the third Big Star record if I played music at all.”

Peter Jefferies, Dunedin, 1980s.

In December 1985, Jefferies penned a downbeat, information-rich letter to his new friend Bruce Russell, which indicated his current malaise and less-than-certain future. It took the television debut of the Chris Knox-filmed video for ‘Randolph’s Going Home’ in March 1986 to shake Peter from his torpor. He hadn’t even known the clip was out. “Maxine Fleming, Graeme’s girlfriend, rang me up to say how great she thought [‘Randolph’] was. The video was rough. Chris Knox filmed it for thirty bucks in his backyard with two great big lights he got for something else. He poked a few holes in some of the lens caps and changed them over and we played along to the single on the stereo. The whole thing’s a little bit fast, but hey, there you go.”

‘Randolph’s Going Home’ made an immediate impact. Richard Langston summed the record up succinctly in issue four of Garage, his detailed, historically accurate and fast-developing Dunedin fanzine. “This Kind of Punishment’s Peter Jefferies has a reputation as a perfectionist and true to form he took nine hours to lay down this drum line. Doublehappy Carter wrote ‘Randolph’ and it was always going to be good, but Jefferies made certain. Both players stick to their recognised styles, and they meld beautifully. Dark and anguished, but eminently accessible, this may be one of the most powerful 7-inches of vinyl ever released by Flying Nun. Over the careful drum detonation, Carter delivers a great vocal and when his guitar crunches in, it’s huge and devastating.”

‘Randolph’s Going Home’ was a big step forward for both artists. Peter Jefferies moved closer to the more accessible sound of the Dunedin groups while Carter gained gravitas and a new sound dynamic that had been largely missing from his previous efforts. The single very nearly made New Zealand’s pop charts, Peter recalls. “It came close to the Top Fifty. Number 52, I think it got to. Two more points. And the clip was the first video of anything I’d done that made the TV. It made me really want to go back to Dunedin. And, if it doesn’t sound too arrogant, there were certain people there who really wanted me to come back because of ‘Randolph’. It healed a lot of people or as much healing as could be done. But ‘Randolph’s Going Home’ gave me a profile in Dunedin, and I knew Bruce down there and he was a mover and shaker.”

--

An excerpt from Peter Jefferies – The Other Side of Reason, by Andrew Schmidt (Hozac Books, Chicago, Illinois, November 2024), published with permission.