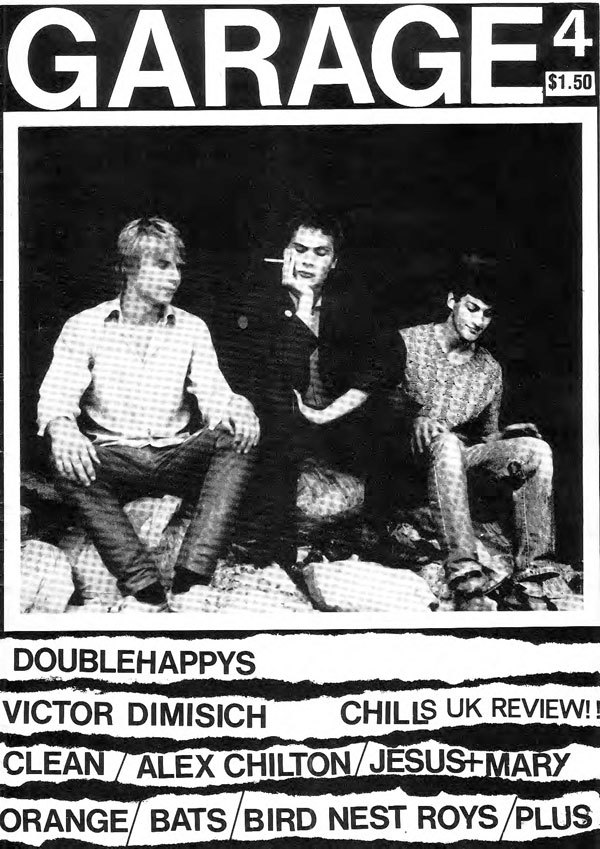

The poster for Garage 4

It is peculiar how one thing leads to another, how a random event influences your life.

In the early ’80s on my OE, I met a young Spanish guy who told me he’d kept himself fed in London by masquerading as a journalist, cadging albums off record companies, and then selling them.

It was the impetus for me to try something similar, the difference being I was a journalist (and carried my NZ journalists’ union card to prove it). Never mind that I was a callow one, with only a fan’s enthusiasm for music, and a threadbare knowledge of rock history.

I soon found myself interviewing Grant McLennan of The Go-Betweens at Rough Trade’s warehouse in north London. He was mannerly, acutely aware, and Australian, a combination new to me at the time.

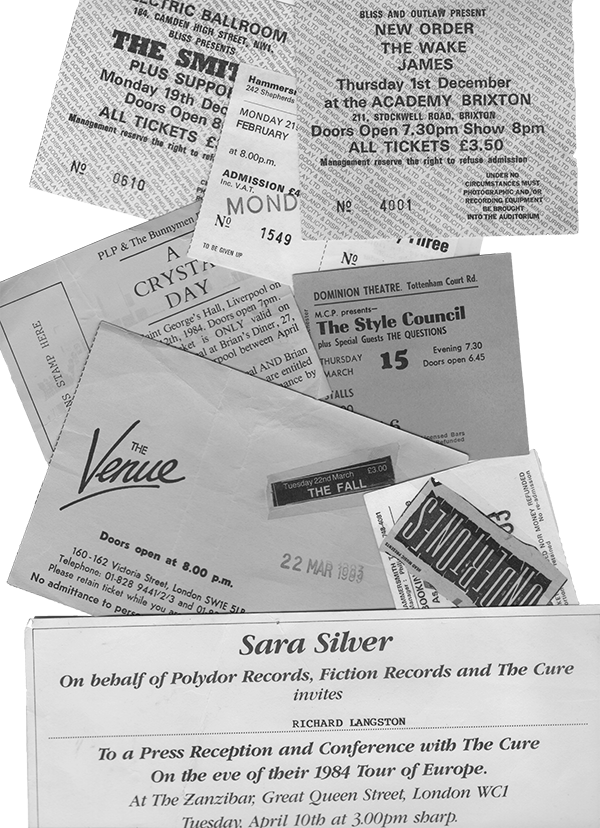

Richard Langston's UK concert tickets, 1982 to 1984

I graduated to interviewing Rough Trade’s rising star, Morrissey, in his Kensington apartment (a cover story for RipItUp); the witty Scotsman, Edwyn Collins of Orange Juice, at the offices of Polydor records; Mike Mills of REM, on their first tour of England; the amiable DJ John Peel, over a curry; Billy Bragg, in the tiny tatty office of Go Discs; Ian McCulloch of Echo & The Bunnymen, in Liverpool; the wonderfully engaging Matt Johnson of The The; and a slightly bored Paul Weller.

Richard Langston's Echo And The Bunnymen story in Sydney's Stiletto magazine, 1984

Thus a sideline in music journalism began, and it was very much a sideline: I also worked as a cycle courier and would have the odd experience of turning up at a record company one day to interview one of its stars, then perform the minion’s task of racing one of its parcels across inner London the next.

When I returned home to Dunedin in September 1984, there were no pop stars. After London, life was slow; it gave the appearance of almost having stopped. I liked it. Dunedin is one of those places that rewards digging down into its hidden layers. Grant McLennan turned up on tour with his band at one point and said, ‘What are you going to do here?’ He was genuinely curious.

Richard Langston, Dean Allen and Victoria Scott, Oriental Tavern, 1985 - Photo by Pat O'Neill

As it happened there couldn’t have been more to write about. Dunedin was alive with bands, not just ordinary bands, but bands that were taking their first or second steps to becoming hallowed names in alt rock circles around the world (not that we knew that at the time).

Following on from the initial explosion of The Enemy and The Clean, the city was in the midst of its second great flowering – The Chills, The Verlaines, Sneaky Feelings, The Rip, The Puddle, The Orange, Doublehappys, and Look Blue Go Purple. Bored Games and The Stones had been and gone, The Great Unwashed was underway, and Snapper lay ahead.

From the Richard Langston archives – a Chills setlist from Dunedin in July 1985

The first interview I did was with Robert Scott. The Bats had released their debut EP By Night. The story, for the then-national Sunday newspaper The New Zealand Times, began: "Two flights of battered stairs and three wrong turns and we’re into the room of a pop star."

Robert, like most of the musicians I’d talk to in the next few years, was skint and lived in one of the city’s faded, tumbling-down grand old houses. It made for cheap, if spartan living. When I started Garage it, too, was typed and glued and stapled in a room in one of those drafty old villas.

Garage Headquarters, St Kilda, Dunedin

The fanzine was kick-started purely by the energy and fumes emitted by the bands in their often-startling live performances. Besides The Chills and Doublehappys, The Rip and The Verlaines burn particularly brightly in my mind from those days in early 1985. They all featured in the first two issues.

There were no restrictions, no advertising to worry about, and no budget. We only looked to cover costs with the asking price of a $1 (a dizzying $2 by issue 6). It would be as many pages as we had the energy to muster.

We were lucky enough to attract writers who broadened the scope. Bruce Russell knew the history of the Christchurch underground, and of dark wonders from further afield such as This Kind of Punishment.

David Swift, a New Zealander working on the NME in London, also contributed generously. David and I had met in London and had championed the Flying Nun bands. I took 7-inch singles and EPs to the Rough Trade shop, and helped get them to John Peel at the BBC, and David ensured The Chills, The Great Unwashed, and others were reviewed in the NME’s then-hallowed pages.

Chris Knox draws on back of an envelope sent to Garage

I met another writer at the Otago Daily Times. Alistair Agnew sat across from me in the newsroom. He was far more interested in the poetry of Allen Curnow and Peter Olds, and rock music, than chasing fire engines. He was in a band that did a cover of a B-side by the Go-Betweens. He was a natural fit.

A fellow called Ian Henderson was foolish enough to favourably review us in the Southland Times, and he was immediately press-ganged into service. As was Dean Allen, a legendary fixture at Dunedin gigs, and a man whose house sagged under the weight of his record collection.

Over some rather dodgy wine, in marathon mid-week sessions in a room stacked with books, records, and yellowing copies of the NME, he ensured I became schooled-up on the right bands from rock’s past. Some people go to university; I went to Dean’s.

The musicians were extremely generous too. Chris Knox and Hamish Kilgour not only gave us interviews, they sent us graphics and art works. The last issue, number six, was a run of 1,200, tiny by mainstream standards, but rather large for a fanzine, especially one that had an initial photocopied run of about 100.

Record stores, too, came to the party, putting us on their counters, and sending back the proceeds vital to our continued existence. I sent copies to the Rough Trade shop in London, rather neatly completing the circle where my sideline career had begun.

There were those perplexed – my father no doubt among them – over why I devoted so much time to this handmade bedroom endeavour, when I had a proper career to get on with, a house to buy, a family to start.

Of the media I’ve worked in – newspapers, radio, and television – Garage is the only one that had no financial reward. But it’s the one that keeps returning, the one that still seems to serve a purpose.

Bands from all over sent Garage their records

In 2011, when Flying Nun marked 30 years, the six issues were digitized and put on its website, accompanied by podcasts of the music that inspired them. They found thousands of new readers and listeners.

As the guy says in that song, "Some things you’ll do for money, and some you’ll do for fun, but the things you do for love are gonna come back, one by one."

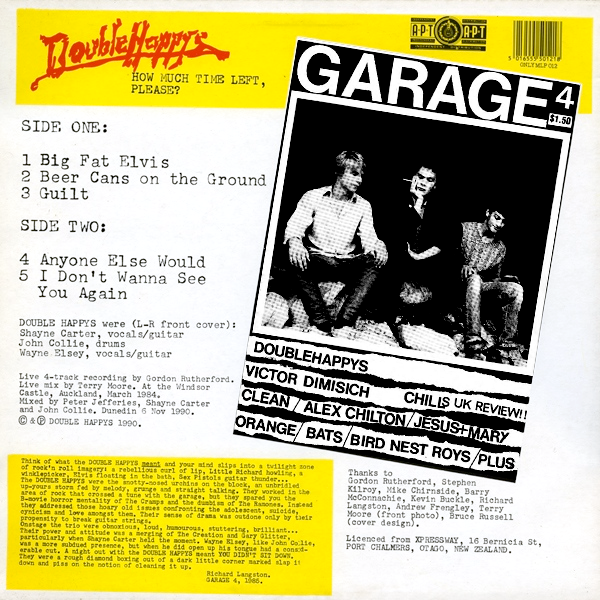

Garage on the back of a rare Doublehappys release on Scottish label Avalanche Records, 1990

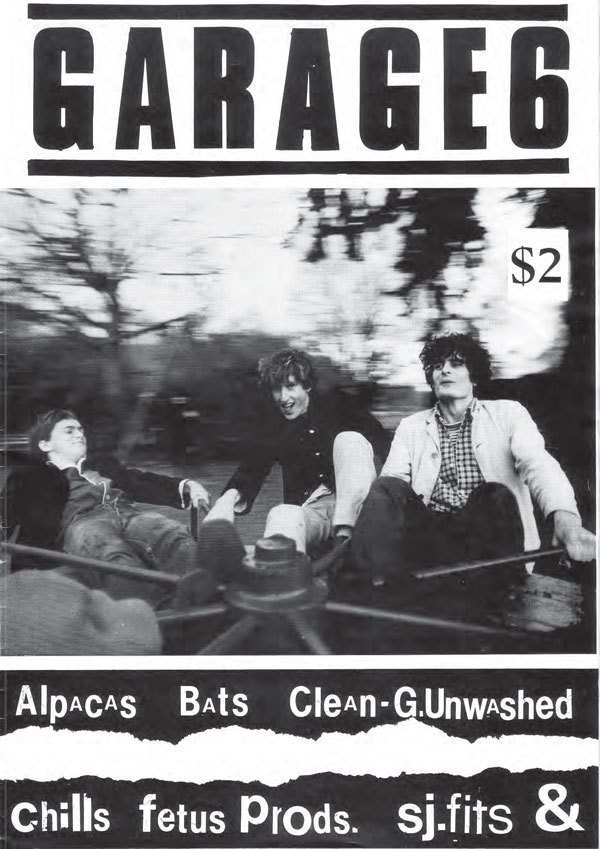

The poster for Garage 5

Garage featured in the cards marking ten years of Flying Nun, 1991

All images and ephemera courtesy of Richard Langston.

--