In the 1960s, New Zealand had some major pop music successes and Mr Lee Grant was the biggest of them all, the star of 1967 TV show C’mon. The singer had six Top 10 singles and three No.1 singles in just 15 months. A year later he was gone, his image untarnished, unlike many of his contemporaries who continued to perform on the increasingly bland music shows on television.

In a sense this profile is the view of a 13-year old boy, as that was my age when Mr Lee Grant had his two biggest hits.

Mr Lee Grant has been viewed as a mere “product” of three late 60s phenomena: teenage music TV coming of age in 1967 with C’mon, Radio Hauraki coming on air in December 1966, and the Wellington HMV Records pop-factory hitting its stride. What is forgotten is that Grant also worked live relentlessly in the two years prior to his first hit single, he had a mod style of his own, and he was astutely managed by the equally young Dianne Cadwallader.

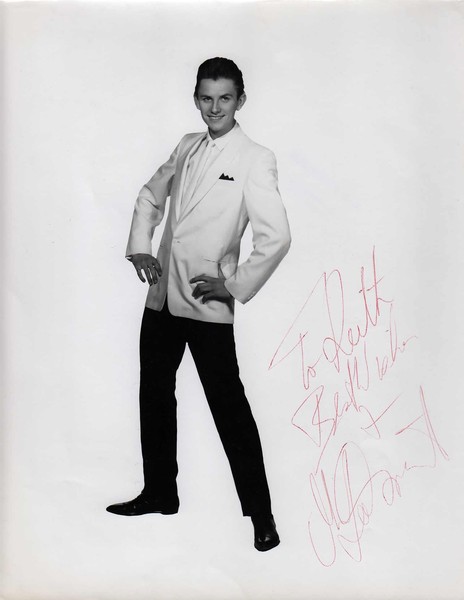

Mr Lee Grant packs his mod threads, c1967

Some local rock writers have looked down at 1960s pop, but it has gained a new respect in the new millennium. Great recording studios have been described as “Temples Of Sound”: unique, sometimes humble structures that have created many of the world’s classic recordings. One of New Zealand’s qualifying studios was Wellington’s HMV Studios on Wakefield Street. There should be a plaque there, marking the spot where legendary 1960s and 1970s recordings were made by Mr Lee Grant, Allison Durbin, The Avengers, The Fourmyula, Shane, Mark Williams etc; with producers such as Nick Karavias, Howard Gable, Peter Dawkins, Alan Galbraith, and studio founder and engineer Frank Douglas.

Commenting on the “HMV Sound” of the late 60s and 70s, producer Alan Galbraith said, “Big sounding pop records are what we all wanted to produce. Lee’s were among the best, no doubt about that, but he also had this huge voice, which helped. We all preferred working with solo artists, session musicians and arrangers like Don Richardson and Garth Young. We were also more interested in pop records, singles and the charts than trying to make an artistic statement!”

Refugee

When Mr Lee Grant came to public attention, he stood out from the crowds of musicians seeking fame as pop musicians – his height, his clothing style, his good looks, his resonant voice and even his back story.

In 1993 the singer spoke to radio journalist Bryan Staff about his early years: “I was born Bogdan Charis Kominowski in 1945 in Dusseldorf, Germany, just as the war ended, and my mother was a refugee. [Grant’s father died in a Nazi concentration camp earlier in the year.] We came to New Zealand on a refugee scheme. We were farmed out to Christchurch, to stay with a very nice family. When I was about six or seven we went to Hawera where my mother worked in a boys hostel. There were about 100 Polish boys and I was the youngest. From there we went to Palmerston North where I was raised and educated. Then I went to Palmerston North Teachers College and then Massey University.”

Grant’s back story created a curious headline in the Auckland Star in 1967 at the peak of his success: “Jailed For His Singing”. This refers to an incident that occurred prior to his departure from Germany that was retold in the C’mon tour programme: “His first public appearance can be claimed at the age of four when the day before leaving Germany he sang the Polish national anthem on a table top in a restaurant. His reward was to spend four hours in jail while his mother arranged his release.”

When newspapers were studiously trying to avoid pop music, every misfortune that came Grant’s way was perceived by cynical journalists as a publicity stunt engineered to achieve a headline. Doubts were even raised as to whether his childhood biography was true. When the singer won The Entertainer of the Year Award in 1967, the NZ Herald gave it 3cms and the Auckland Star 4cms.

Mr Lee Grant, before going "mod", c1965

Mod style

In early publicity photos when the teenage singer was signing his publicity photos “Bog”, he already had a very stylish look. At six-feet, one-inch tall (185cm) he was the perfect clothes hanger for suits and big coats.

“He always knew how to dress,” Cadwallader told me in 2016. “I never saw him badly dressed.”

Grant was so European in style, even though he grew up in New Zealand. In the decade that started with Barry Crump’s bestselling book A Good Keen Man, the singer from Palmerston North did not appear to shop at Keans for Jeans. A teen eyewitness, John Saunders, saw Grant being chased by female fans through Stafford Arcade in their mutual hometown, and thought “this guy is obviously on to something!”

Other New Zealand males were jealous of teenage affections directed towards the singer. Even Dene Kellaway, the editor of local music paper Groove – and an aspirant pop star himself – admonished Grant for his excesses: “C’mon, Lee, surely you don’t have to dress up like a doll to sell your discs. How about an improvement in your appearance? OK?” Grant had just left the country.

Colin Cleave, former owner of Auckland record store Revival Records, wrote about meeting Mr Lee Grant in 1967 when the singer was wearing a mink black coat given to him by designer Gerry Broughan. Cleave recalled a jealous musician saying to him, what a “wanker" Lee Grant was and that he intended to stand near Lee one night with a cigarette. “If that coat’s nylon it’ll go up like a rocket – his carry-on is way over the top. What bloke wears a fur coat?”

Cleave wrote that Cadwallader said the fur coat “was part of the marketing strategy: ‘it looks classy, Lee looks brilliant in it’.”

“I must have said something like that,” said Cadwallader (who is now appalled by the wearing of fur). “They wouldn’t just make it up. I am surprised I would have used the term marketing in front of two fans. Gerry gave it to him. It was an absolutely beautiful coat.”

Cadwallader was not claiming to be naïve in respect to marketing and business skills: “My mother was a very successful business woman. She had two fashion stores. I learnt how to do business from her.”

Dianne Cadwallader, manager of Mr Lee Grant, New Zealand's biggest star of 1967.

In 1993 Grant spoke about his clothing style to Bryan Staff: “Gerry Broughan of [Wellington boutique] His Lordship, had just been to Carnaby Street. He brought the pop image to New Zealand. We became very good friends. I used to borrow his gear to wear on C’mon. Then he gave me gear to wear in exchange for publicising his gear. I think I wore the first bell-bottom-trousers. At the time I don’t think I particularly liked them. They were very strange to wear, but everybody seemed to like them, so I just went along with the rage.”

“Once when I was running on to the [live] show, I did not have time to do my tie up – to put it into the knot – I left it hanging over the top. The next day six students were expelled from school for not wearing their ties correctly. But it was just an accident.”

Grant’s look is hip again with mod aficionados. On the cover of 2012 German bootleg compilation Mod Meeting International Vol. 7 (Dr No Records) he is pictured in a design that emulates his debut album; his track ‘Love’ is included.

But in 2016 when he spoke to Radio New Zealand’s Grant Walker he was dismissive of the gear. “The look was intentional but I hated the clothes. I was a surfie who wore jeans and a T-shirt but I had the wrong colour hair. I always wanted to be blond. Gerry would come up with these weird and wonderful clothes. I’d go to his shop on a Friday night and have tartan bell-bottoms and all sorts of gear that I would wear on television. Kids would go mad over those clothes.”

Maybe Mr Lee Grant was not a ‘Dedicated Follower Of Fashion’. Alan Galbraith, a pop contemporary, recalls Lee’s style: “I wasn’t really into fashion at all, but Lee was keen. He and Sandy Edmonds were kind of Mr and Mrs Mod, more as a result of their managers’ ideas to make them real pop stars. Most of us got good deals from Gerry Broughan at His Lordship in return for wearing his gear. The big stars got free clothes. You have to remember that most of us didn’t want to be ‘musos’: we wanted to be pop stars. Also, the term ‘mod’ got to mean something other than what real mods were wearing. I think the first mod pop star was Dinah Lee and there were a few real mods in Wellington back then, but Lee looked nothing like them.”

Getting started

In a November 1967 Weekly News cover story Grant reflected on his years before pop stardom. “It was good when I was at school and training college as I was unknown and I could play as much sport as I liked, and make as many blues as I liked. Now it is different. I can’t join a tennis club because everybody is either out to beat me or get in my way, just because I happen to be a pop singer. If I go surfing – which I am not very good at – people come along and laugh and hope that I ‘wipe out’.”

“You can’t be called Bogdan Kominowski, because no one can say it, so you’re now called ‘Lee Grant’.”

Grant also spoke of his early music influences: “First it was Gene Pitney, then Roy Orbison, then PJ Proby, whose style probably influenced me most.”

Where did his stage name come from? In 1993 he explained that the influential 1960s Napier radio DJ Keith Richardson called up and said, “You can’t be called Bogdan Kominowski, because no one can say it, so you’re now called ‘Lee Grant’.” Lee was after Cliff Richard’s dog and Grant was after a friend’s dead brother. Rumours that he was named after the American Civil War Generals Lee and Grant were erroneous.

In Richardson’s memoir Never A Dull Moment he explained that his wife Sylvia came up with the name Lee Grant after “a great deal of correspondence” with the young teacher trainee. Richardson and his wife introduced Grant to Hawkes Bay, booking him to appear with local bands that they mentored, such as The Rockets.

A 1963 gig at the concert chamber of the Palmerston North Opera House featured The Rockets (“Hawkes Bay’s top recording band”) plus Lee Grant and the scintillating Cyclones. The concert took place two weeks before his 18th birthday. He was now known as Lee Grant: Auckland would later add the “Mr.”

Although based in Palmerston North and attending teachers college, the young singer worked with Richardson, who was a promoter on the side and an enthusiastic supporter of local talent. The DJ kept in touch with the Wellington records labels to obtain on-air prizes and inform them about local talent.

When Peter Sinclair quit as host of 2ZB’s weekday Sunset Show and his Friday night The Late Show in 1967, he suggested Richardson as his replacement: he hosted Napier’s Saturday night Top 40. So the Hawke’s Bay’s pioneering disc jockey moved to 2ZB in Wellington.

A manager

Two career paths crossed in late 1965. Auckland music journalist Dianne Cadwallader was asked by a friend to see Lee Grant and give him some publicity via her Sunday News entertainment column “Show Bitzers”.

She wrote in her column of 11 July 1965: “Confusion ahead! Palmerston North’s top MALE vocalist, Lee Grant, is heading for Auckland in August – knowing that English Lee Grant is a FEMALE vocalist getting a lot of work here. Perhaps Lee Grant (male) could abbreviate his real name – Bogdan Kominowski.”

Cadwallader recalled that when she first saw Grant rehearsing, “I believed he had a star quality only a few entertainers have.” In August 1965, she took on handling his PR and bookings, getting Grant work at Dave Dunningham’s ballrooms. Also that month, under a photo in the Sunday News that showcased the “sultry” look, she wrote: “Meet Lee Grant, 20-year-old singer from Palmerston North. He was in Auckland the other day and took the opportunity of ringing his female Auckland name-sake. Female Lee welcomed him to her ‘territory’ and name changing was discussed, and how he will be billed as Mr Lee Grant. Mr Grant may soon come back to Auckland as a permanent resident.”

While in Auckland, Mr Lee Grant recorded the single ‘Doo-Doodle-Do-Doo’ for Gary Daverne’s Viscount label, backed by The Sierras. Released in late 1965, the single made no impact but was re-released two years later on the Zodiac label, to capitalise on the success of his second No.1 single for HMV, ‘Thanks To You’.

An Auckland manager and promoter phoned Cadwallader and asked her to visit his office. She assumed he had a scoop for her Sunday News column or some PR work for her. The manager was affable, but said, “We want this boy’s management.”

Cadwallader recalled, “I kind of laughed and I said ‘his management is not available’.”

“We want him,” insisted the manager.

“I said, ‘I’m doing his publicity and when he needs a manager, we’ll look at it’.”

Then, Cadwallader recalled, the manager got very menacing, saying, “If we can’t have him we’ll run you out of Auckland and you won’t work again.”

“Lee didn’t want a bar of him either,” she recalled. “I obviously went back and told Lee all of it and if Lee had said ‘I want him to manage me’, I would have taken him to [the manager, who is still alive]. But Lee’s gigs were cancelled that day.”

With no Auckland work, they decided to head south and build Grant’s career out of Palmerston North and Wellington, where the big record companies were based. They would be closer to South Island work and the regions where Grant grew up. Cadwallader’s final Sunday News column was 31 October 1965.

Diane Cadwallader at her parents home in Levin, 3 February 1968. Note the album in her briefcase. - Horowhenua Historical Society, Inc; CC licence 4.0

Fifty years later, Cadwallader attributed this incident to the fact that she was an independent operator/manager, not the fact that she was a woman. The venue owners, who were organised as NEBOA (National Entertainers and Ballroom Operators Association), also wanted to exclusively manage and book the artists.

She stressed that times have changed since the mid-1960s. “We’re post-feminism and post all kinds of things but in the 60s a woman could not have a bank account unless her father guaranteed it. It was a way of ‘protecting women’. But seriously, women were not expected to speak. A lot of people wanted to see me undone.”

To use the expression of the time, Cadwallader officially became Grant’s manageress “under contract” in mid-1966. For some people, having a young woman manage a musician was a joke. Grant was constantly asked what it was like to have a woman – his own age – managing his career. “We get ribbed about this, but we don’t mind,” Grant told the New Zealand Herald in 1967.

Also that year the Auckland Star described Cadwallader’s management style: “Now she handles everything from decisions of where and when to perform to telling him what to wear – while I was talking to her, she told him he was not going to wear a purple corduroy suit and tie for a show that evening. She does not make a decision on questions of major importance – tours for example – without consulting him and considering his opinions. ‘We fight regularly but we never come to blows.’ She and Grant are ‘just good friends’ and she finds managing his affairs a handful.”

The Rolling Stones

Mr Lee Grant attended The Rolling Stones concert at the Wellington Town Hall on Monday 28 February 1966. There are photos of the Wellington police having to restrain a fan who had grabbed hold of Mick Jagger. Within a year, Grant would soon face teen hysteria himself, in less secure venues.

On the day of The Rolling Stones concert, Mr Lee Grant recorded two songs for Ron Dalton of Viking Records. The following day, in a letter to mentor Keith Richardson, Grant wrote, “Saw the Stones Monday night show – ended in a riot – you know, fainting fans, cops etc … Cut two great sides for Ron on Monday – will be released March sometime.”

Two weeks later, in another letter to Richardson, Grant wrote, “Have had a lot of trouble myself. I’m not recording for Viking. At the contract stage, Ron turned me down with no reason at all. You know how it is in this business. I was very disappointed, but I have been accepted by another good company, so I hope to have disc out within the month. I can’t tell you the company but as soon as I’m able I will inform you. Everything seems to have changed since the Viking double cross. (please don’t quote me on this, but that’s what it was).”

After rejection by two record companies, Grant considered returning to teaching. The Auckland Star wrote that his manager “bludgeoned him into his decision to try again” and he was offered a record contract with HMV.

“Bludgeoned” suggests that some journalists were scathing of Cadwallader’s management style or it maybe they were just acknowledging the singer’s debt to his manager. The company Grant was referring to was His Master’s Voice (NZ) Ltd.

Mind How You (Went)

The first HMV single was clearly an elaborate and expensive production. “I loved doing ‘Mind How You Go’,” recalls Cadwallader. “Patrick Flynn, who did the orchestrations, did it beautifully. It really deserved to be a very big hit.”

When ‘Mind How You Go’ was released in late 1966, there was only one chance of a single being played on radio, as there was only one broadcaster in the country. If the NZBC didn’t like your record, it would not be heard.

At the peak of Grant’s success in 1967, entertainment journalist John Berry recalled meeting Grant a year earlier. “I sat in a Wellington home chatting with a longhaired young singer about the problem of achieving a breakthrough in the record business. Mr Lee Grant was a disillusioned young man. NZBC radio men were being difficult about giving ‘Mind How You Go’ airtime.”

One reviewer, Wendy Munro of the Sunday News, was unimpressed by the big budget single. “Despite 24-piece backing by the NZ Symphony Orchestra, the number is a let down. Backing is claimed to be the biggest ever in Australasia, but vocal work is drowned out and patchy, and the number just doesn’t come across.”

C’mon – the pilot

In September 1966 Berry reported in the Sunday News that “show biz” talk in Auckland was that three TV entertainment show pilots that would in a teen show called Come On! Only one of each show would be produced in 1966, “then the NZBC will decide which it wishes to expand into regular production as a series in 1967.”

Two months later, Berry wrote that earlier in the week the Come On! pilot had been recorded. When the show screened, he was so impressed, he wanted to give a special award to TV producer Kevan Moore. “His Come On! show is the brightest thing which has happened on New Zealand TV this year – and the most exciting light-entertainment show ever produced by the NZBC. Already, the corporation has decided to take the plunge and run to 26 Come On! shows in 1967.”

Grant was selected to appear on the pilot edition of Moore’s new Auckland-based TV pop show, C’mon. In November 1966, the pilot was screened and well received. Grant was booked to be resident on the 1967 season, which would run from February to July. Moore worked with promoter Phil Warren of Fullers Entertainment to assemble the talent. To appear on the show, Grant had to be booked by Fullers, but the singer and his manager were pleased to be able to work in Auckland again.

Pirate radio

Radio Hauraki arrived in December 1966, giving musicians another outlet for airplay. The station had a lot of airtime to fill with pop music: from before dawn to after midnight. Hauraki co-founder David Gapes told AudioCulture, “Mr Lee Grant was huge in the 60s, especially with teenage girls. Those were the first days of star/radio cooperation: the mutual endorsement was really worth something then. Hauraki thrashed his hits, promoted his gigs (usually with our deejays as MC). We worked very closely with his manager Dianne Cadwallader.”

Both Gapes and Cadwallader were former newspaper journalists. “I’d known David Gapes forever, Radio Hauraki was very good to us,” she said. “Hauraki played New Zealand music. I don’t think others did, except for the Loxene Golden Disc finalists.”

Although Grant’s 1966 single had not charted, he had played some key gigs and gained some TV exposure. At a Christchurch concert, Australian pop star Normie Rowe found the local singer a very hard act to follow.

Mr Lee Grant on the cover of Teen Beat, August 1966

Grant was a popular act on the teen dance hall scene in the lower North Island, and he appeared on the August 1966 cover of Teen Beat, but HMV was slow to commit. The green light to record four more tracks was not given until mid-January 1967. Producer Nick Karavias explained to radio host Keith Richardson in an April letter, “I was right about Lee all along because at one time in this office everyone was running him down. After the ghastly mess they made with ‘Mind How You Go’ (and you know very little of the background of that fiasco to fully appreciate the situation) it was only C’mon that saved him.”

Go-Go tour

After Christmas 1966, the two-week “Sandy Edmonds A Go-Go” summer tour hit the road. The Gremlins were on the bill and had to back all the solo singers. Their lead singer, Glyn Tucker, recalls, “It was a great tour of the beach resorts, crowds were incredibly enthusiastic for all acts on the bill. Although Mr Lee Grant was virtually unknown at that time, he stole the show every night. Screaming teenage girls were a force to be reckoned with. His good looks and superb showmanship made him stand out from the average. It was no surprise to me that once C’mon hit our TV screens he became a real pop star.”

With the real C’mon season due to start in February 1967, Edmonds, Grant and Larry’s Rebels were on the road with the Roy Orbison, Walker Brothers and Yardbirds tour. Redmer Yska wrote in AudioCulture about the tour, “The competition was intense … Grant, nevertheless, managed to out-cute them all. Photos from the show record … welcoming signs draped by adoring Grant fans. Bogdan Kominowski was on his way. The ecstatic reception he got that night helped launch his career, a career that would go through the roof that year.”

While Grant was based in Auckland for C’mon, he broadened his audience with a cabaret floorshow at the Colony nightclub in Wellesley Street. In mid-April he joined one of Harry M Miller’s star-studded tours: Eric Burdon and the Animals; Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich: Paul and Barry Ryan; and Larry’s Rebels.

Riot in St Heliers

Grant had been seeking fame as a singer for five years and when it arrived, fame smacked him in the face. An Auckland suburban dance in nice St Heliers was the first time his manager was fearful of the actions of fans. She recalls watching Grant from the side of the stage and thinking, “Don’t lean over any further.”

“Auckland pop singer Mr Lee Grant is ‘brassed off’ with the suggestion that the mauling he received at the hands of his hysterical fans last Saturday night was a publicity stunt.”

POP STAR HAS HAIR TORN OUT. I still recall the headline on the front page of the New Zealand Herald on 24 April 1967, although it’s a lot smaller than I remember it. The article reported: “An Auckland pop star, Mr Lee Grant, lost a handful of hair when hysterical teenagers hauled him off stage at a dance in the St Heliers RSA Hall on Saturday night. He had just been handed a cake for his 22nd birthday. As he bent down to hand it to some girls he was thrown to the floor. Security guards fought their way through a mass of tangled bodies to reach the singer. He was taken to the back of the stage where he collapsed. Police escorted him from the hall through screaming teenagers after he had been revived. He was taken to Auckland hospital but was later discharged. Five attempts had been made to pull him off stage while he was singing.”

Once again Cadwallader was accused of creating a publicity stunt. A headline in the following weekend’s 8 O’Clock said: NO STUNT, POP STAR AFFIRMS. “Auckland pop singer Mr Lee Grant is ‘brassed off’ with the suggestion that the mauling he received at the hands of his hysterical fans last Saturday night was a publicity stunt.”

Grant was yet to release his first hit single.

Cadwallader recalls, “The St Heliers gig: that’s the first time I ever felt that Lee was in physical danger of any kind. It was very early on. I remember thinking we have to be extremely careful. One of the famous ones was down at Mataura, north of Invercargill. People came from miles and miles around to this tiny little country hall, in the middle of nowhere. He was utterly trapped. They called all the police from everywhere. The only way he got out of that village hall, [was] he swapped clothes with a policeman. So everybody thought Lee was still in the back but he’d gone out dressed as a policeman. He told me he had to keep his head right down, so they couldn’t see him.”

Forty years later, Chris Self, drummer for Invercargill’s The Answer, described backing Mr Lee Grant at a country hall in Thornbury to the Southland Times. A mob hysterical fans stormed the stage, pushed and scratched the band members, and tore at their clothes.

“To be honest with you it was a bit scary,” recalled Self. “We were playing and [Mr Lee Grant] was on stage. I have this vision still in my head of this wave of people coming over the front of the stage. It all just happened. Bang! They were mobbing him and we just happened to be in the way. We were swamped. Then these bouncers appeared and started pushing everybody off the stage’. After the show Grant was locked in the hall cloakroom, where he signed autographs on pages ripped from a policeman’s notebook, which were handed to the screaming fans outside.”

Mr. Lee Grant grapples with hysterical teen mania at Auckland Town Hall, 1967

“Fans can be terrifying on mass like that,” said Cadwallader. “There was a young woman staggered out of the St James Theatre in Wellington and she just walked right in front of a bus, was hit and broke both her legs. At Wellington airport when we were flying to Auckland to fly out to England, a young girl broke through the fence and ran out in front of the plane. Hysteria!”

What did Cadwallader call her friend with two names? Her answer shone light on how the singer coped with perils of fame. “Most of the time I called him Bogdan.”

“Lee had a great ability – he was very willing to treat himself as a product – he could see that this would be a good move for his career. He wasn’t a diva. There was nothing diva about him. He was a pleasure to work with. Product is probably not the right word, but he was quite willing to take a step back and see there was Bogdan Kominowski and there was Mr Lee Grant and this was happening to Mr Lee Grant. That’s my impression of it.”

Lipsticked

“Please, girls let’s not get hysterical” was how the Sunday News headlined an appeal for calm in April 1967. “In the past few weeks his home life has been disrupted by girls (most of the school-age group) lying waiting for him in the drive-away of his apartment building, so that even a trip to the corner dairy has become a sortie. A crowning act of stupidity came the other day when he returned home to find hysterical messages of affection scrawled on his front door and windows in lipstick.”

When Grant and his manager moved into the same Remuera street – of all the streets in Auckland – as Miss Lee Grant, the cabaret singer’s name was in the phone book as “Grant, Lee.” While appealing for more intelligent behavior from teens, the newspaper wrote: “Another more than annoying act is the constant flow of phone calls directed at Mrs Lee Grant by girls asking to speak to Mr Lee Grant. Let’s get this straight. The two Lee Grants are not in any way associated. Mr Lee Grant does not have a phone. Mrs Lee Grant is being upset constantly. For goodness sakes, let them have some privacy.”

“Girls looked up Lee Grant in the phone book and got her address … they lipsticked the house,” said Cadwallader. Of course, the real fans knew he lived across the road and cleaning lipstick off the front of the apartment was a regular chore. With a girls’ school nearby, the Remuera address was a disaster. “Then we moved to Herne Bay, Bellavista Road. I don’t think anyone found out. The Chicks lived across the road.”

Opportunity knocks

When Grant did his first session for HMV producer Nick Karavias, among the four tracks they recorded was the Bee Gees song ‘Spicks And Specks’. Although the song had been a hit single in Australia, this was apparently of little importance to the New Zealand record company.

Songs for local acts were usually found from the many singles not released locally or by choosing album tracks off foreign albums. For a New Zealand musician to write their own song would be deemed arrogant by the NZBC, as there were plenty of good songs that could be sourced from London.

‘Spicks and Specks’ was to be Grant’s second HMV single, but in 1967 The Bee Gees released the song as a single in the UK. Its success there led to a New Zealand release where it promptly headed for No.1 on the local hit parade. HMV had to rethink their plan to release Grant’s version. ‘Opportunity’ became the A-side, backed by ‘Spicks and Specks’.

A month prior to its release, however, Karavias at HMV did not seem to be a fan of ‘Opportunity’. He wrote to Richardson, “Regardless of our publicity and advertising ‘Spicks And Specks’ is the ‘A’ side and that’s the side I am pushing. However regardless of which is the ‘A’ side or the ‘Best’ side, the orders are coming in thick and fast.”

Grant said in 1993, “A sound engineer called Nick Karavias dug up this song called ‘Opportunity’. It was in a totally different rhythm. I thought up the rhythm: I tried to copy the rhythm of the Spencer Davis Group’s hit ‘Gimme Some Lovin’.”

‘Opportunity’ entered the New Zealand chart 19 May 1967 – the very day that the Bee Gees single ‘Spicks and Specks’ hit No.1. ‘Opportunity’ was the track radio played and Mr Lee Grant had his first No.1 record. It stayed on the charts for 10 weeks, and HMV managing director, Alfred Wyness presented the singer with a silver disc for 10,000 sales. Grant later told Groove music paper that his version of ‘Spicks and Specks’ reached No.1 in Fiji.

Mr Lee Grant with his master: HMV (NZ) Ltd's formidable managing director Alfred Wyness, 1967

Although Grant’s hit singles were cover versions, the lyrics were vaguely autobiographical. ‘Opportunity’ did come knocking on his door with his residency on TV’s C’mon. ‘Thanks To You’ seemed an appropriate sentiment as his fans assisted him to win 1967’s key awards. ‘Movin’ Away’ was released prior to his departure for London – and the 1968 finale ‘Bless You’ was a fitting goodbye song.

With Mr Lee Grant at No.1 on the New Zealand charts, he joined Radio Hauraki’s Queen’s Birthday weekend “Big Beat Dance Jamboree” alongside Larry’s Rebels, The Chicks and The Clevedonaires. The week-long tour played from Whangarei to Mt Maunganui. After the 9.30pm show at the Mount, Grant was was due to go stage at Auckland’s Top 20 nightclub at 2.30am. The Sunday News was breathless with anticipation: “The Top Twenty’s Stan Blenkin will be standing-by at The Mount to drive Lee on the 160-mile dash back to town.”

On the cover of the Women’s Weekly

A few weeks after his first hit single in 1969, Grant quickly made it on to the cover of NZ Women’s Weekly. “He’s made his name initially without the help of a hit record – something unique in the New Zealand pop field,” wrote Lesley Barrett. “That intense expression (Lee objects to being dubbed ‘sultry’) is liable to change any minute to a cheerful grin – plus his deep, classically trained voice, appeals to quite a proportion of the older generation as well as the young set. That’s the way he likes it.” The 21 year old pop star was fashion-aware: “I am going through a brown phase at the moment. Don’t like gaudy colours – the ‘total look’ of matching outfits is more distinctive.”

Grant acknowledges the importance of C’mon for himself and local music. “C’mon taught me how to appear on television but it’s not an easy medium. You don’t just stand in front of the cameras as some people think. With television you get through to people, but I feel I’m cheating because it’s all mimed. With C’mon there are so many artists bubbling just underneath the surface it seems the Australian dominance is wearing thin and New Zealand’s finally emerging in its own right.” The writer adds: “Thanks to Mr Lee Grant, it is.”

Riot grrrls

Colin Cleave’s blog about being a teenage Mr Lee Grant fan in 1967 is an eye-opener, showing just how down-to-earth their idol was in real life. In June 1967, Cleave was waiting outside the C’mon studio in Shortland Street. The 30-minute show had gone to air at 7pm and the cast would then watch the playback. Colin and his friend Greg thought if they asked to see David Gapes it might make them seem legit. “As they approached the door Di Cadwallader came out and they tried their question. “He’s in Australia,” was the reply, as she proceeded to her car. That didn’t work.

Cadwallader asked them, “I see you boys around a lot – are you fans of Lee?”

“Yes,” they replied in unison.

Cadwallader said, “I’m just waiting for Lee to come out of the studio and we are going to do a show at Auckland Girls Grammar School. Would you boys like to come with us?”

Their reply was obvious – “Yes” – and as Grant emerged, Cadwallader said, “Lee, these boys are coming with us to watch the gig”. He replied, “Great, it should be a gas, guys.” They piled into Grant’s two-door, two-tone, Triumph Herald car. The drive to the school included a sharp left turn and a U-turn by Grant to try and get rid of a tailing car of girls. But the girls caught up at the next set of lights.

For an Auckland native in 1967, this was a five to 10 minute drive. These out-of-towners soon got lost with only 20 minutes to show time. Lee broke into song, ‘We’re only 24 hours from Tulsa’, which delighted Colin and Greg but not Cadwallader. “We may as well be 24 hours from Tulsa if we are not going in the right direction,” she said.

Cadwallader told the fans in the back seat what they probably already knew. “Lee has a three and a half octave vocal range and can sing an even higher ending to Gene Pitney’s ‘I’m Gonna Be Strong’ – sing it to them.” Grant replied, “Not while I’m driving, I can’t.”

The school was found but, as they feared, fans were everywhere as they neared the stage door. Dianne asked her passengers to help. Cleave wrote, “Fans rushed Lee and backed off Di as she gave off the ‘don’t mess with me’ vibe. Greg, Dianne and I flanked Lee as we moved towards the stage door. We were pushed and shoved as we escorted Lee to the entrance. I felt on cloud nine, as we were part of his team. Safe inside, Lee took his coat off and handed it to me, ‘Will you wear it until I come off stage,’ he asked, ‘otherwise it’ll get pinched for sure’. I couldn’t wait to put it on. Wow! Me standing backstage wearing Mr Lee Grant’s black, short-haired mink coat. Lee looked every inch a pop star in his mod-tailored, silver, three-piece suit and wearing smooth pointed toed black Beatle boots. ‘I think I’ll throw my tie into the audience,’ said Grant. ‘I generally loosen it during ‘Land of a 1000 Dances’.”

From side-of-stage, encased in fur, Cleave observed: “The lights to the entire hall were turned off. Lee started to sing unaccompanied the beginning of ‘Maria’ from behind the curtain. Immediately the screaming started, the atmosphere was electric. The quality of Lee’s voice was instantly apparent – its richness filled the whole hall and the darkness made it even more magical. The fans knew he was there but couldn’t see him yet. He slowly sang, ‘The most beautiful sound I have ever heard, ‘Maria, Maria’ – and on the last ‘Maria’ the curtains slowly parted and a spot light was on his head and shoulders. When the curtains fully opened the band started up and the whole stage exploded in light. The audience just erupted, left their seats and rushed to the front of the hall.”

Mr Lee Grant with fans

The tie that Grant threw into the audience caused mayhem. Two schoolgirls would not concede possession of it. The school principal wanted the two girls ejected while they were both still clutching it. Judge Dianne stepped in: “I told them the student that does not keep the tie can meet Lee after the show. Instantly, they both dropped the tie.”

The school insisted on an encore that prevented Grant from making a safe, early getaway. The competitors for the necktie came back stage, met their idol and received autographed photos. Cleave recalls their delayed departure: “Looking from the rear window of Lee’s small sports car, I saw over 100 girls running after the car. As they followed many were screaming, waving their arms and crying out for Lee. It was as though dozens of Sandie Shaws, Twiggys and Dusty Springfields were chasing our car.”

Everything was a “gas” in Grant’s lingo, but buying petrol was difficult. The headlights that tailed them that night included a mum and her daughter, followed by a friendly Auckland Star reporter, Toni Lester. The trusty Triumph Herald needed petrol … and Grant’s followers soon crowded the station forecourt. This was Grant’s life in fast lane – 1967 style.

“I was happy about that article,” Cadwallader said of Cleave’s blog. “It gave the flavour of what our life was like – you couldn’t stop for gas, you couldn’t go to the movies. That period – I guess it was a six month period – he was very, very, very famous.”

Later in the year, Grant had become a pro at the tie throw. He spoke to Groove newspaper about his “gas new clothes, all by His Lordship of course. You know I’ve given away 56 ties so far on this tour. I throw them off the stage and the fans move in on them pretty fast.”

One hit single into his career, and Mr Lee Grant’s life in the fast lane would soon pick up pace.

--