AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Jet Jaguar

aka Michael Upton

Since his early experiences playing in warehouses around Wellington, to multimedia performances in Tokyo nightclubs and back again, Upton has maintained his position as one of the more inspired, inventive and consistent electronic music producers in New Zealand.

During the mid-80s, Art of Noise, Yello, Harold Faltermayer, Paul Hardcastle, Herbie Hancock and their peers transformed the chart music landscape by releasing instrumental electronica records that sat comfortably against – and sold as well as – traditional pop songs and ballads. The influence of these records spread as far as New Zealand, where for Wellingtonian Michael Upton, now better known as Jet Jaguar, they served as the soundtrack to his teenage years.

“Art of Noise’s music was based on sampling, so it was essentially found sound,” he recalls. “They’d chop up dogs barking, cars starting, and make musical ideas out of noise. That really blew my mind, and I was very excited by it.”

With this as his starting point, he became interested in electronic music, industrial rock and the possibilities presented by synthesisers, and more crucially, sample-based music production. “I wouldn’t have used these words at the time, but a common thread for me was the idea of creating music using a much wider palette than just playing instruments.”

When Upton was 16, his friend Tarn McDonald’s mother (who worked as a piano teacher) purchased a MIDI keyboard. Tarn began playing around on it and successfully sequenced up a song by Nine Inch Nails and a couple of songs by The Cure. “I got really inspired. So I went and worked on a farm over the summer holidays and saved up,” Upton remembers. At the end of the holidays, he bought a Roland D-5 sequencer and an Akai S-1000 sampler.

Upton spent his final year in high school playing with friends in a couple of bands and writing his own music at home. After high school, he spent some time playing in an ambient band named Monkey Shuttle with Stuart McDonald and Andrew Loughnan, before focusing on his own efforts.

Upton was an early internet user. From 1995 onwards, online mailing lists, email, and forums allowed him to start connecting with other bedroom music producers around the world. “Everyone uses the internet as part of their daily life now,” he reflects. “The idea that cultural connections would happen via the internet is almost taken for granted and not even a topic of discussion for people now. It’s the default way of operating, but back then the internet was weird. I remember when having an email address was kind of embarrassing and a sign of being overly nerdy.”

Discovery by discovery, he began to connect with a local network of electronic music producers, DJs, and event promoters.

Upton started spending time in record stores and going to warehouse raves around the city. Discovery by discovery, he began to connect with a local network of electronic music producers, DJs, and event promoters.

“At the time, I felt like the only way I could reach people was through playing live or taking tapes and later CD-Rs to student radio,” he says. “It was the only way I felt like anyone outside of my circle of friends would hear what I did.”

Years later in 2000, the network of connections led to him organising an international remix chain, with 20 different producers around the world taking part. “That was great fun, but someone had to build the website we used to share the parts of the tracks from scratch, and there was no facility to comment. All communications were handled by email.”

After attending local electronic music showcase Psychic Droid at the short-lived Biosphere venue in the early 90s, Upton decided to take live performance more seriously. Given the futuristic tone of the names producers around town were using (Polarity, Oblique, LRS, etc.), he decided to go against the grain. “I said, stuff this. I don’t feel any connection with that futurist aesthetic or technology driven way of thinking about music; I’d much rather have a laugh.” Looking backward, he decided to name himself after the giant flying robot from 1973 Japanese science fiction kaiju film Godzilla vs. Megalon – and Jet Jaguar was born.

Things went to the next level for Upton after he approached one of the staff behind the counter at a local record store with some of his demos. That staff member was DJ Mu (of Fat Freddy’s Drop). Mu introduced Upton to Simon Swain, a founder of New Zealand electronic music website and record label Obscure. Serendipitously, Swain was in the process of assembling Skankatronics Pure Wellingtronika, a compilation of music from Wellington-based electronic producers. When the compilation came out in 1996, it featured Upton’s first official release as Jet Jaguar, a song called ‘Seeper’. “Through that experience, I met all of the artists on the compilation,” Upton says. “One of them was Bevan Smith.”

By that stage, Smith was recording under the names Signer and Aspen and had established himself as a respected electronic music producer. Much like seminal underground New Zealand labels Xpressway Records and Yellow Bike Records, Smith wanted to use DIY channels and smart networking to establish a record label and get New Zealand made electronic music to the world. The record label would be called Involve, and Upton was in the mix from the start. “Bevan saw very early on that the largest audience would be outside of New Zealand,” Upton recalls. “He had a great idea to kick the label off. He would do a solo album, I would do a self-titled solo album, and we’d do a duo album as Patio.”

Involve’s launch helped Upton build a national profile as Jet Jaguar. Touring, student radio support, and interviews and reviews in the Evening Post, Real Groove, NZ Listener, Remix, Sunday Star-Times, Dom Post and Pavement followed. His rising profile also led to placements on a number of locally released compilation albums. He also went on to create remixes for the likes of The Black Seeds, Aspen, Rhian Sheehan, Fat Freddy’s Drop, Flash Harry, Tim Koch, Group Five, Benny Tones and The Phoenix Foundation.

The music Upton makes as Jet Jaguar has generally been downbeat in its most experimental or exploratory mode, with the odd foray into house and techno along the way.

Built out of chopped up funk samples, instrumental hip-hop and dub production techniques, found sounds and ambient synthesiers, the music Upton makes as Jet Jaguar has generally been downbeat in its most experimental or exploratory mode, with the odd foray into house and techno along the way. Although he initially drew influence from the instrumental electronica and hip-hop of the 80s, and classic Jamaican dub of the 70s, Upton had a forward leaning approach. He wanted to take advantage of the compositional freedoms and possibilities afforded by electronic music production. Upton could see the potential to really try new ideas out in a fraction of the time had taken to write music in the past.

“In terms of process, my music is often quite literally experimental, in the terms of trying something out rather than being weird for the sake of it,” he explains. “I’m usually working through some ideas in my head and don’t quite know what they will sound like.”

As his reputation grew, Upton began playing shows around New Zealand and Australia alongside a mixture of local and international musicians including Prefuse73, Monolake, Salmonella Dub, Pitch Black, King Kapisi, Tim Koch, 50 Hz, The Nomad, Architecture in Helsinki, Marineville, Cloudboy, and Mink. During this period, he also became more active as a musical collaborator through working alongside Barnaby Weir, Bret McKenzie, Tim Jaray, Toby Laing, Lee Prebble and Mike Fabulous in Dub Connection, and Datsun Stereo with his childhood friend Tarn McDonald.

“In 1999, Lee Prebble recorded Barnaby Weir performing a song he’d written over a 70s Studio One reggae instrumental. Barnaby brought a copy of the song to me and asked if I’d remix it,” he remembers. “My remix became the one that got radio play, and Barnaby came up with the project name Dub Connection. A bunch of the usual suspects came together to form a full band.” Dub Connection performed live two years running at Radio Active 88.6FM’s Waitangi Day One Love Festival in Wellington.

On the Radio Active songs of 2000 chart, the Jet Jaguar remix of Dub Connection’s ‘All the Goodness’ was named No.2, and his remix of The Black Seeds’ ‘Coming Back Home’ topped the national alternative charts.

In 2000/2001, Upton was flatting in Wellington with McDonald. They’d go op-shopping together and look for party records that were great to dance to. Upton had started playing the odd funk, soul and hip-hop DJ set around town, so the advice was appreciated. While they were living together, they collaborated on an EP as Datsun Stereo. “Tarn probably makes my favourite local dance music, but has hardly released any,” Upton says. “He did an album worth of excellent 80s style boogie as Pierre Omar in the 2000s, back before anyone cared about that sound.”

Around the same time, Upton started appearing as a guest DJ on Radio Active 88.6 FM’s soul affair show. “We used to trash talk a lot, give shouts out to all these girls who were never calling up, and so on, it was great fun.”

Near the end of 2001, Upton relocated to Melbourne. Once he was settled, he started collaborating with Shanan Holm on their ambient project Montano. That same year, his song ‘There’s A Choice We’re Making’ was included on Autumnature, a US-released compilation album assembled by Boston ambient producer Greg Davis. “Again, the connection came about through a music mailing list.”

While he was living in Melbourne, Upton started recording for Brent Gleave and Jason Harding aka DJ Clinton Smiley’s Capital Recordings label. In 2003, he released a self-titled 12" EP and his second album Think About It Later through Capital Recordings, before releasing his third album Jet Jaguar Is Love through Involve.

That same year, Capital Recordings also released 12" EPs from Dub Connection and Datsun Stereo. In 2005, they released a self-titled album from Upton and Holm’s Montano project. “Capital Recordings were really good,” Upton says. “They had plenty of resources behind them and a lot of enthusiasm from Brent and Jason. They were well connected in terms of local promotion, so it was excellent for my profile in New Zealand. As far as I know, Think About It Later was my biggest selling release.”

Jet Jaguar Is Love and the self-titled Montano album were both featured in music critic Grant Smithies’ book Soundtrack: 118 Great New Zealand Albums. Of Jet Jaguar Is Love Smithies said, “It’s so special you can set your CD player to repeat until your mind begins to float free.” In 2003, Think About It Later was included in music critic Jim Pinckney’s best albums of the year list for the NZ Listener.

Between 2005 and 2010, Upton took a break from Jet Jaguar and focused his efforts more towards Montano and Malty Media (a collaborative project with Stuart McDonald). “I was a bit jaded from shopping my fourth Jet Jaguar album around and not getting any takers,” he admits. “It was still a time when I felt I needed a label, and I can’t pretend I didn't feel pretty gutted.”

Upton and McDonald had written music together on-and-off since 1994. While they were working together, Upton relocated to Tokyo, and McDonald came to visit for a performance. “With Malty Media we had this grand idea of basically recreating something a la the early days of ambient house, like KLF’s Chill Out or the first Orb releases,” Upton explains. “We wanted it to be funny rather than earnest. Stuart came to visit in Tokyo and we performed as Malty Media to a (literally) underground venue of Tokyo techno heads, mashing up Country Calendar footage with ambient house remixes of the ‘Goodnight Kiwi’ TVNZ music. We asked ourselves: New Zealanders talk about Japanese pop culture like it’s from another world, what if we flipped that and presented funny or kitsch aspects of our own back to some young urban Japanese?”

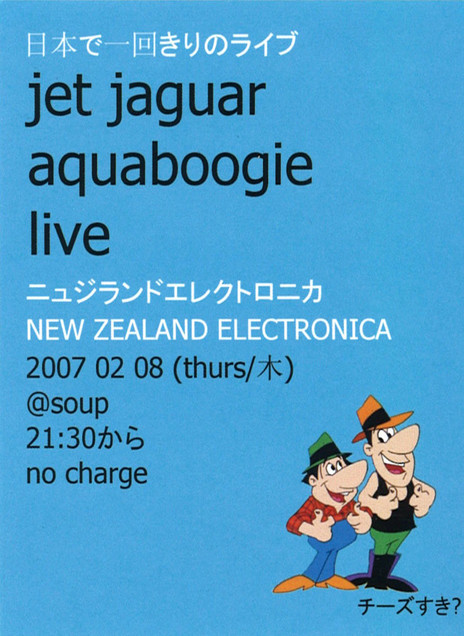

In the 2000s, online internet labels were becoming a solid platform for connecting electronic music with an audience. McDonald had been recording and releasing his own material as Aquaboogie with a few of them, so he handled pitching Malty Media’s material through his networks. US internet label Monotonik ended up releasing Malty Media’s Bracken Bed EP in 2007. In 2008, they released an EP of new Jet Jaguar songs titled Biddy Bids.

“A song from Bracken Bed, ‘Flakiest’, unexpectedly got a lot of attention from student radio etc back in New Zealand,” Upton remembers. “It’s a spaced out dub track that turns into a junglist rinse out of the tune from the adverts for Cadbury Flake. It was probably 100 percent illegal, but we were giving it away, so whatever. We took the three most clichéd drum and bass breaks and stacked them all on top of each other, packing in the usual switch ups and dynamics that we thought were the bog standard gestures of the genre. When people started gushing about it, it kinda felt churlish and snobby to admit we were taking the piss.”

In late 2007, Upton returned to Wellington, where they continued Malty Media through ambient DJ sets at Katipo café and live performances at venues around town. Upton quickly got back in rotation as a DJ on Radio Active 88.6FM, but this time he was playing on the weekly ambient show instead of the Soul Affair. “It always makes me smile that I moved from the soul show to the ambient show, but it covers the two main veins of music I’m interested in,” he reflects.

When the option came up, Upton started hosting a fortnightly Malty Media show with McDonald on the station. They’d select other people’s music and perform 15-20 minutes of new material every week as well as applying ambient effects and live processing. “Looking back, it was a massive undertaking and no great surprise I wasn’t spending much time on any solo material separate to that,” he says. Upton and McDonald also teamed up with Andrew Loughnan to assemble a compilation of local electronic music titled Apropos Of Nothing.

Since 2013, Upton has released a steady stream of Jet Jaguar EPs online.

In 2010, McDonald moved overseas and Upton shifted his focus towards Jet Jaguar again. In 2012, he self-released his fourth album Four though Bandcamp. For Four, he took his unreleased demos from the mid 2000s and asked a crop of emerging young electronic music producers including NAT WLKR, James Skylab, Samu, Shanalog, Stephanie E and K*Saba to remix them, before packing up their efforts with his originals. In his words, “I was still writing new material, but I felt like I wanted to do this to say something about a continuum I felt I was a part of where this old material linked through to scenes that were still active, and challenge the idea that instrumental beat-based stuff was faddish and bound tightly to a particular time and place.” That same year Upton and Holm also self-released their second Montano album.

Since 2013, Upton has released a steady stream of Jet Jaguar EPs online through Bandcamp. In 2013 he released the Single-Digit High, Shreds, Many Things, Lucked Out, Sounds, and Five Production Mistakes Even Professionals Keep Making (They're Not What You Think) EPs. In 2014, he released Hoops. 2015 and 2016 saw him release Many Meters and July respectively. He also made semi-regular contributions to an online series of composition challenges called the Disquiet Junto.

Although he admits he’d be more than happy to continue working with record labels, and intends to again in the future, self-releasing online has come with some advantages. “It’s really freed me up to think about what I want to hear as a listener,” Upton enthuses. “Typically I like quite short releases as opposed to the bloat of an 80 minute CD. I realised I had the opportunity to do them. Another thing that really hit me after writing music for quite a while is I don’t mind if only a few people hear it. I’d always love to have more people hear it and do some stuff to promote it, but actually if I put stuff out easily and perhaps reach fewer people maybe that is okay. It’s also a matter of thinking about, what are the bits that I care about the most and where do I want to focus my effort? For me, that is writing music, and collaborating with other people, connecting with them through the experience of making music, rather than wrestling to find an audience.”

The 2016 release of July marked 20 years since ‘Seeper’, Upton's first release as Jet Jaguar. Over the course of two decades of performances across New Zealand, Australia and Japan, and countless releases, he’s continued to return to a desire to articulate, as he puts it, “A sense of atmosphere or feeling I can’t describe,” in the process keeping himself inspired to continue creating regardless of commercial recognition or mainstream visibility.

“Basically, for me, music creates an environment. It’s something that surrounds me and changes how I think or feel,” he says. “We’ve all had that feeling of putting on a pair of headphones in a certain situation and suddenly feeling like we’re in a movie. I’ve always loved that about music, that and the physical aspects of cranking a tune really loud. The reality is I always have that nagging feeling that I want to be doing that as well. I want to contribute and create atmospheres that I don't hear unless I create them myself.”

Updated 13 January 2017 by Martyn Pepperell

Involve

Capital Recordings

Monotonik

Angry Rabbit

Grind Productions

Black Widow Productions

Radio Active 88.6FM

Surgery Records

Golden Bay Records

Atom heart

Aktivator

Member of Monkey Shuffle, Patio, Dub Connection and Malty Media.

Upton has been heavily involved in online music culture since the early days of the internet. He maintains a personal music blog at www.nonwrestler.com.

Jet Jaguar is named after a character in the movie Godzilla vs. Megalon.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air