Allwright was born in Wellington on 7 November 1926, then spent his early years in Hawera before returning to attend Wellington College. As a teenager he heard jazz for the first time via US Armed Forces programmes broadcasting from transmitters in Titahi Bay. These radio programmes were a revelation, exposing him to the music of a young Sinatra, along with Louis Armstrong, the Benny Goodman Sextet and the big band sound of Woody Herman and Stan Kenton. Allwright would queue in Wellington record stores, desperate to buy the 78rpm jazz discs imported for the US Marines stationed at Paekakariki on the Kapiti coast.

Around this time Allwright also began to hear American folk songs on the radio; these made a big impression on him and would eventually lead to his later success as a musician in France.

At the age of 21 he left New Zealand and set sail for Liverpool.

Even though he came from a musical family which would often sing together around Wellington in hospitals, churches and school fairs, Allwright initially had no ambitions of becoming a singer. Instead, he devoted himself to acting. He started performing at the age of 15 with the Wellington Repertory Theatre and in 1948 was awarded a bursary to attend the prestigious Old Vic Theatre School in London. And so, at the age of 21, he left New Zealand and set sail for Liverpool, working as a deck hand to pay for his passage.

His acting career began to flourish in London, with Allwright making valuable contacts in the industry; he was offered a place at the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford, England. However, at the age of 21 he turned this opportunity down, instead moving to France with Catherine Daste, a fellow student at the Old Vic who came from a respected family of French actors. The two had fallen in love, so Allwright followed her across the Channel to work as a carpenter, using the skills he learnt from Wellington college, building sets for the Comedie de Saint-Etienne travelling theatre company. The two eventually married in France in 1951. Before embarking on this new life, Allwright spoke virtually no French, although he had picked up a little at school in New Zealand. While touring around France with his father-in-law’s theatre company he would carry a small dictionary to look up certain words, but it took him years to become truly bilingual.

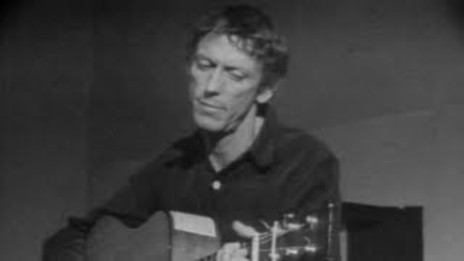

Allwright then settled for a short time in Burgundy to work in the vineyards. He also ran a theatre group in Pernand-Vergelesses, where he performed the work of Bertolt Brecht. It was around this time that he began to buy the records of American folk musicians Woody Guthrie, Tom Paxton, and Pete Seeger, and first started to play the guitar. But he still found himself unable to settle down, moving to Blois where he worked in a psychiatric hospital before starting a children’s theatre and teaching English in Dieulefit. While living in Dieulefit, Allwright discovered his aptitude for translating English into French, by adapting New Zealand stories into French as a game for his students.

He was living in Saint Étienne when he first had the idea of translating the folk songs he loved into French. These initial attempts were well received by friends and family who encouraged him to perform them in public. This gave him the confidence to start playing regularly in small Parisian cabaret venues in the early 1960s, accompanied by Genny Detto on guitar. While performing in the Contrescarpe cabaret he became friends with the singer Collette Magny, a political activist who went on to become one of France’s first protest singers. The Contrescarpe was also the venue where Allwright was eventually discovered by the well-known actor and singer Marcel Mouloudji, who felt the time was right for a bilingual singer with a left-wing perspective. He was impressed with Allwright’s ability to adapt the lyrics of revered contemporary songwriters such as Cohen and Dylan, a responsibility the New Zealander didn’t take lightly.

“It’s not easy – if you want to respect what they’re trying to say in the song – and also get it to rhyme and sing well. You mustn’t feel that it’s an adaptation or translation. You must feel that it’s absolutely a French version which is perfect.”

Allwright’s cover versions were carefully translated and sung in fluent French.

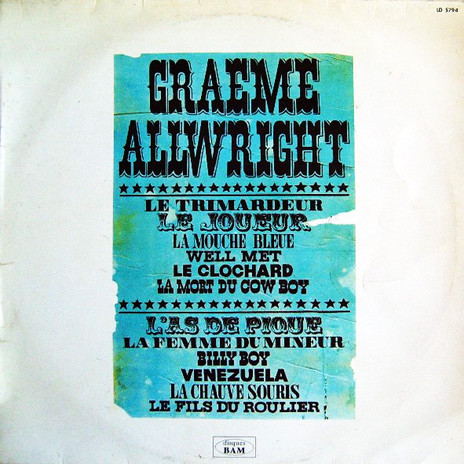

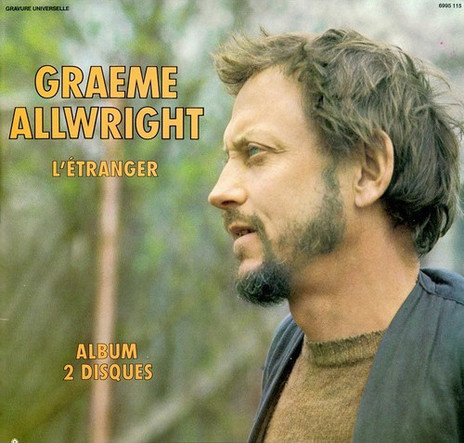

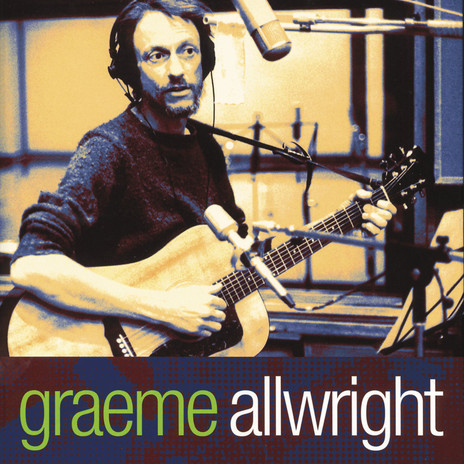

In 1965 Mouloudji decided to produce Allwright’s first album Le Trimardeur (Disques Mouloudji). By this point, Allwright was in his late 30s, a relatively late age to become a recording artist. But, according to Allwright, this gave him the chance to gain a broad understanding of the French language and build an appreciation of various types of slang, which helped him to adapt songs in a naturalistic style. Although Allwright’s cover versions were carefully translated and sung in fluent French, some listeners could still detect a slight accent.

However, according to François Ribac, a composer, sociologist and senior lecturer at the University of Bourgogne in Dijon, this wasn’t an issue. “He had an accent, but in popular music in the 60s and 70s in France you could find many successful artists in different kinds of scenes who had accents. You had Jane Birkin, the wife of Serge Gainsbourg – and Petula Clark, who had a lot of hits and had a huge career in France, Switzerland and Belgium. So to have a slight English accent was something good. It added something – so it was not a problem.”

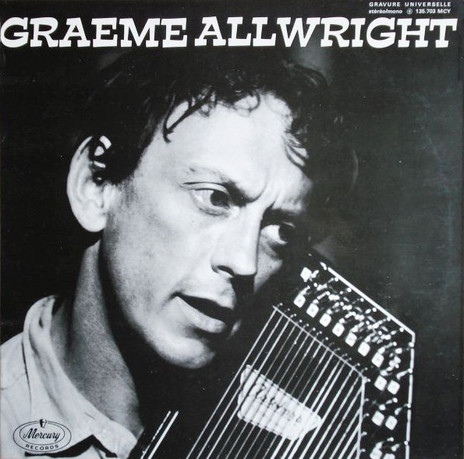

Allwright’s debut album was recorded on two-track tape in two sessions lasting just three hours each. The resulting 12 songs – 10 of which were adaptations – became a calling card in the music business. He was quickly offered a recording contract with Phonogram and released his second album, Graeme Allwright, in 1966.

His music was especially resonant with the Parisian protest movement of 1968. Unrest against the conservatism of the Gaullist regime led to a series of student occupation protests and nationwide strikes, which eventually brought down the French Government. Political and social change was in the air and Allwright’s songs were perfectly timed to capture the mood of the young protesters.

He didn’t just sing protest songs – he joined in, and even found himself caught up in the middle of a riot in the Latin Quarter of Paris. Armed CRS police were moving in on his group of protesters from several directions. According to Allwright, it was a dangerous situation, but luckily he managed to escape by running off down a side street. Although his music become closely associated with the protest movement, the significance of the connection wasn’t entirely clear to him at the time. “The young people, the ‘soixante-huitards’ of 68, filled up the places where I was singing and were singing my songs. I realise now, afterwards, the impact of certain songs. I didn’t realise at the time how important that was.”

Allwright’s third album Le Jour De Clarté, released during the turmoil of 1968, was produced by André Chapelle and is now regarded as his defining work. It featured his popular version of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Suzanne’, which Allwright believes is his best adaptation: “It’s a wonderful song. It’s sort of eternal.” Allwright went on to record a number of other Cohen songs, eventually releasing an entire album of cover versions in 1973 titled Chante Leonard Cohen. The two met on many occasions and became firm friends.

“He came to my place in Paris and I went to his place when he was living in Montreal – and we remained in touch. When I first started adapting Leonard Cohen songs into French, I had to ask for permission. He listened to my adaptations, which he liked, and gave his permission. He even said later on that he preferred listening to his songs sung by me in French. I think he exaggerated!”

Allwright was overwhelmed by the success of Le Jour De Clarté and on the first of January 1969 he left his young family behind to go travelling around the world, as a way to escape the pressure of his new-found fame. He and a friend set off on a journey that took them through Egypt and Sudan until they reached Ethiopia. Following in the footsteps of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud the two eventually reached the city of Harar. Allwright spent six months living in Ethiopia: “I didn’t even think of the singing career I left behind. I was living something completely different and discovering another world.”

He fell into a pattern of recording an album, then suddenly vanishing to head off on another travel adventure.

Allwright’s wanderings also took him through the US, Mexico, Maghreb, Tunisia, Chad, Gabon, Cameroon, and the Congo. He often travelled to India and in the mid-1970s lived for 18 months on Reunion Island, in the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar. He fell into a pattern of recording an album, then suddenly vanishing to head off on another travel adventure.

This led him to become a sort of cult figure in France, with rumours that his absence was due to him being killed while overseas, or that he had committed suicide. The confusion only seemed to add to his mystique and helped build a reputation for being a “serious”, if elusive, artist. However, his impulsiveness took a toll on his relationships and both of his marriages eventually came to an end. Despite this, Allwright remains close to his two former wives and is on good terms with his four children.

Allwright released two albums sung entirely in English, A Long Distant From Present From Thee... “Becoming” and Recollections, although these weren’t particularly popular at the time, possibly alienating his core audience of French speaking fans. Yet “Becoming”, released in 1970, remains his most audacious work. It’s a sprawling psychedelic album that draws on his experiences in India. Allwright experiments with tablas, processed guitars, eastern tunings and eerie female backing singers. The opening track, ‘The Pen’, is a hallucinogenic epic, over 11 minutes long, and unlike anything he recorded before.

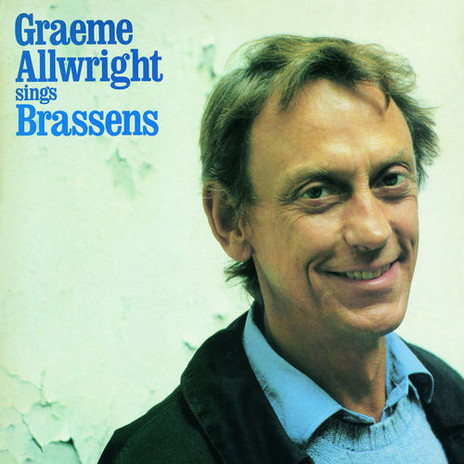

He released a total of nine albums throughout the 1970s, then in 1980 performed a series of concerts with the French star Maxime Le Forestier, to raise funds for children in the third world. This resulted in a live double album, Enregistrement Public Au Palais Des Sports, with all the royalties donated to charity. He released only two more albums in the ’80s, including a collection of George Brassens songs in 1985. In the 1990s, Allwright worked on several film soundtracks, and recorded a live album and an album of songs for children. In 2000 he returned to his childhood obsession with jazz, by recording the album Tant De Joies with the American trombonist Glen Ferris and his quartet. His released only one further album, a live recording with Steve Waring, in 2012.

New Zealand remains close to Allwright’s heart, although he’s only been able to return three times since leaving in 1948. He protested against the French Government’s programme of nuclear testing in the South Pacific, commenting: “My ‘Kiwi’ blood really boiled.” This inspired him to record the protest song ‘Pacific Blues’ on his double album A L’Olympia, recorded live in concert in 1973. Allwright was similarly outraged by the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior in 1985, “I think it was disgusting what they did really. I think that was a very black moment. It’s difficult for me to understand that they [the French Government] went that far.”

Another issue Allwright has devoted himself to is the French national anthem, ‘La Marseillaise’, which he considers to be a military song. With Sylvie Dien, Allwright rewrote the lyrics to make them more peaceful and started a movement to try and get this new adaptation recognised as the official national anthem of France.

“They continue in our time to make it obligatory for small children in primary school to learn these words, which are very bloody. To teach a ‘war song’ to small children, I couldn’t accept that. And with a friend I changed those words, instead of a war song – I’ve converted it into a song of peace. I wouldn’t like my children and grandchildren to learn a song of war. I would say it’s my last ‘combat’, to change the words to the Marseilles. I think it’d be an important day for France when they do decide to change those words.”

Although Allwright’s version of ‘La Marseillaise’ hasn’t yet been officially accepted, it gained considerable exposure through social media following the 2015 terror attacks in France.

In 2005 Allwright made a rare return to New Zealand.

In 2005 he made a rare return to New Zealand and toured the country with saxophone player Lucian Johnson, whom he met by chance in Paris. Johnson put together a small band of musicians to accompany Allwright and they played a series of well received concerts in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch. A French documentary, which captured Allwright’s 10-week visit was released in 2009, titled Pacific Blues.

“It was the first time I had been singing in New Zealand and it was quite moving for me. And to be accompanied by New Zealand musicians too was good. There was an audience there, playing in those small places, and the reception was very warm.”

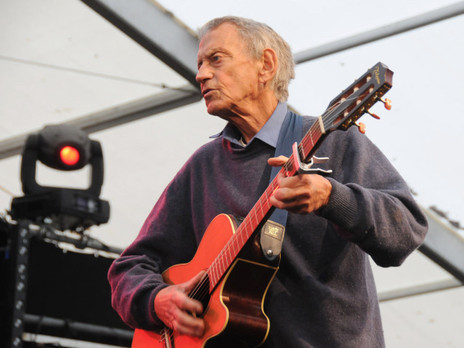

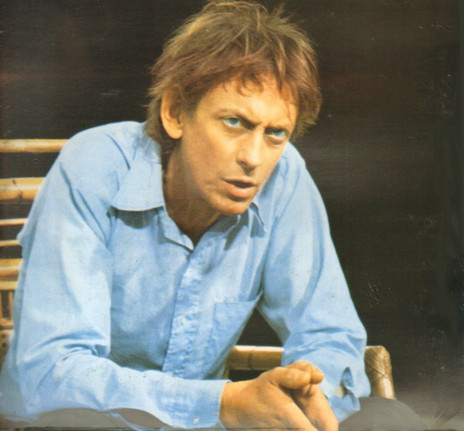

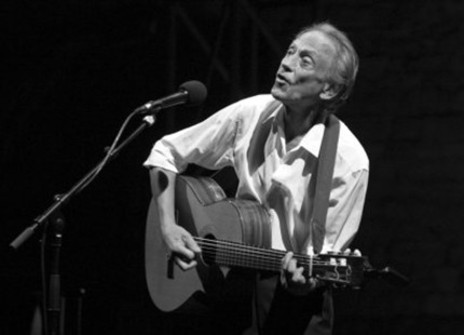

Allwright has been performing as a musician for over 50 years and while his touring scheduled has slowed down now that he’s in his nineties, he hasn’t ruled out further concerts. Francois Ribac last saw Allwright performing in concert in Dijon in 2007.

“He was already very old, about 80, but the charisma of his performance was still so strong. All the audience knew the songs and all the lyrics. He could start to sing a song, then he would stop and then everyone would continue singing. For many French people Graeme Allwright’s songs are part of their lives.”

Although acclaimed for translating the work of other artists’ music, Allwright’s own compositions, songs such as ‘Les Retrouvailles’, ‘Johnny’ and ‘Joue Joue Joue’, have become standards in “la chanson Française”. His music is still sung by generations of French people and his astute adaptations of songs from legendary musicians like Dylan, Cohen, Guthrie and Seeger has made their work accessible to entirely new audiences. But despite all his success as a French singer who has lived in his adopted country for over 60 years, Allwright still considers himself to be a New Zealander, calling France his “second home”.

“I think I’m very lucky to have been born in New Zealand. I think all the physical work which I did in New Zealand has helped me enormously. Also, the solidarity that exists in New Zealand has helped me enormously in going through all the trials which I’ve been through – and overcoming a lot of difficulties. Physically, I think that has given me the ‘force’ to keep on – right up to my age at present. I don’t know how long it’s going to last, but let’s hope that it’ll keep on going. As long as I have the energy and motivation I’ll keep on singing.”

--

Graeme Allwright died on 16 February 2020, in the retirement home in Seine-et-Marne where he had been living for a year. He was 93. His death was covered by many of the major papers in France; the headline in Le Monde was “Le chanteur folk Graeme Allwright est mort.”

--

Sam Coley interviewed Graeme Allwright in September 2010 for Radio New Zealand, and François Ribac in December 2016 for AudioCulture.