It was perfectly natural for the distribution arm of EMI to worry about the potential of their partner’s new signing, given the sales that imported R&B and hip-hop acts were reaping at the time. This home made recording being pitched at them by Reekie – from a white-overalled artist, with a fast and loose attitude to how the industry was supposed to work – did not follow the rules, making Clay appear less than ideal as a candidate to fill the cash registers.

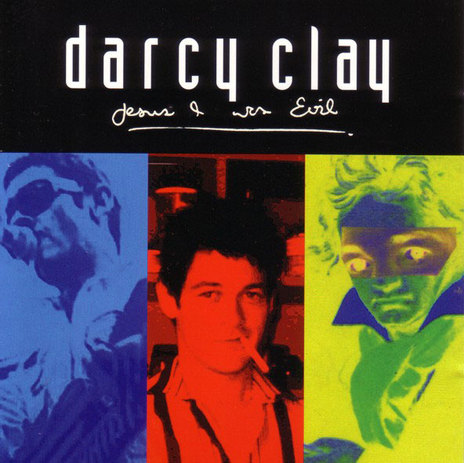

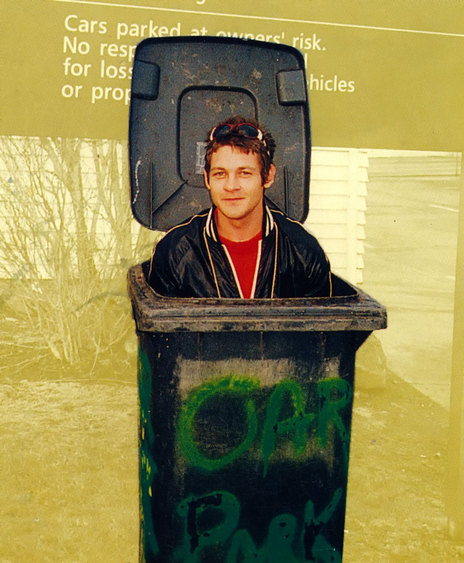

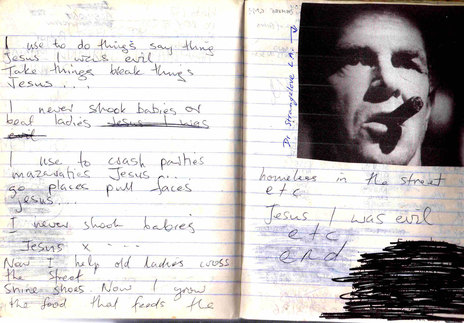

To have reached this point was already some kind of miracle. Clay connected with the right people at the right time, people who could see his unpolished delivery within the three minute borders of ‘Jesus I Was Evil’ for what it was – raw, untamed rock and roll, channelling the same enthusiasm that drove kids to smash up dance halls throughout the United States and Europe in the 1950s.

Bill Kerton was one of the first to pick up on Clay’s brilliance. As programme director of Auckland’s 95bFM – overseeing a boom in the station’s popularity – a copy of Clay’s 4-track recording found its way into his hands via creative director and future Clay collaborator Bob Kerrigan. Without hesitating, Kerton fearlessly threw it into circulation on bFM’s highly coveted playlist and the top of the North Island got their first taste of the Grey Lynn native.

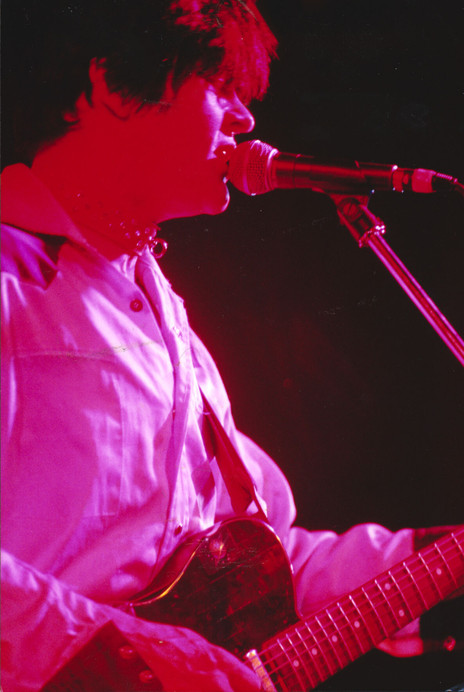

"I like playing guitar, but I like getting it right, and I’m actually – to tell you the truth – not a very good musician. I stuff up heaps, eh." – Darcy Clay

The pace started to pick up in a very short space of time after Kerton opened the door. Gigs for Massey’s Orientation and bFM’s Summer Series beckoned, a record contract was inked, a video clip put in the can and a stylistically bizarre interview with Dylan Taite aired on TV3.

All of these events pushed him further into the limelight, something that sat as oddly with Clay as being lauded for his musicianship.As he confessed to Taite, "I like playing guitar, but I like getting it right, and I’m actually – to tell you the truth – not a very good musician. I stuff up heaps, eh. That’s why studios are good because I can just go over and over and over and over…"

Clay knew much more about working in studios than the legend had it. After ‘Jesus I Was Evil’ was mastered at Progressive Studios – the recording space of choice for a great deal of Flying Nun’s northern-based catalogue – he was given time to work there in exchange for assisting with the acoustic renovations that were so badly needed.

Tim Gummer, the owner of Progressive, remembers. "In reality I would guess that he recorded at least half of his EP in the studio, and the other half at home, which he would bring into the control room to mix later. For the first sessions he was so stoned he couldn’t really concentrate on anything. They were pretty non-productive, frankly, but after a while he found his groove. Quirky production techniques and doing funky stuff to sound are now taken for granted, but he was doing it at a time where most people weren’t. He would put things through processors that weren’t meant to be used for them, which sounds commonplace these days, but back then that wasn’t so done. He would be surrounded with studio quality kit everywhere, but he downgraded himself, as it were, by working on his Portastudio with headphones on. For some reason that environment, just its isolation or something, gave him what he needed. It somehow augmented what he had when he was working at home."

By the 1990s, music without a video clip undeniably spelt death to any aspirations of greater things, and due to his rising popularity the pressure was on to get something together to make the leap to television. Clay had the great fortune to literally bump into a name from his past, David Gunson, while waiting for his coffee at the former magnet for Auckland’s fringe art world, DKD Café. Gunson, an old schoolmate who was now heavily into directing films, readily agreed to the proposal of getting something down onto celluloid. His collaboration with Clay and editor Ian Bennett was done on the most threadbare of shoestrings – a few hundred dollars and a bottle of alcohol, neither of which Gunson saw – and ended up underlining exactly what Clay was like as both an artist and a man.

"While we were driving along I kept saying to him, 'Just give me a line, just sing me a line', says Gunson. "He was very reluctant to do any synchronised stuff to camera. It was hard enough to get him to appear in the music clip itself. I think he felt a bit apprehensive about, not criticism, but putting himself on display. He was wonderful in the way that he would be the most fascinating guy in the room, but he was naturally quite shy. To have something as freewheeling as it was made me a bit apprehensive. It had the potential all the way along to go from a moment caught to just messy images, but things just sort of naturally slid into place."

‘Jesus I Was Evil’ found itself nestled between Joose and Savage Garden at No.5

With his EP and music video now both fashioned into a presentable shape, Clay was released onto the market, which responded by ensuring his debut entered the singles charts at No.18. A week later, ‘Jesus I Was Evil’ found itself nestled incongruously between Joose and Savage Garden at No.5. No New Zealander had tread this close to the No.1 position since OMC peaked at No.4 with ‘Land Of Plenty’, 18 long weeks back.

Jaws at EMI must have been hitting shag pile as they contacted Trevor Reekie, on tour with Greg Johnson at the time, to confirm the news. "They were very surprised about it, but to be quite honest I wasn’t," says Reekie. "I thought it would come in at least top twenty. I was delighted when it got to number five, I hadn’t dared hope that it would go that high, but it did." The tune hovered around the charts for two full months before bowing out in August of 1997.

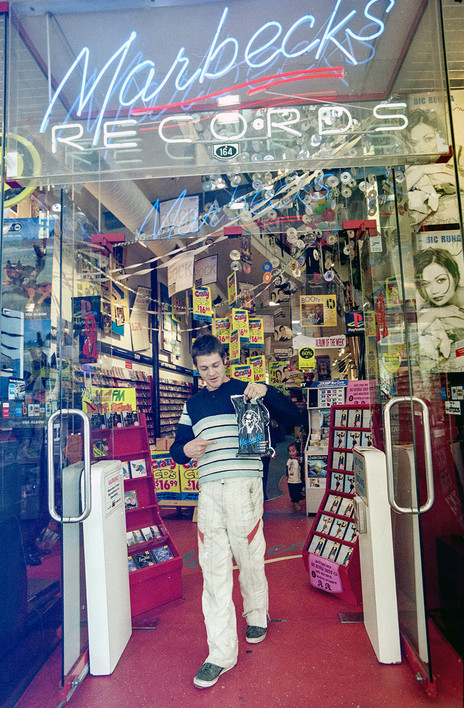

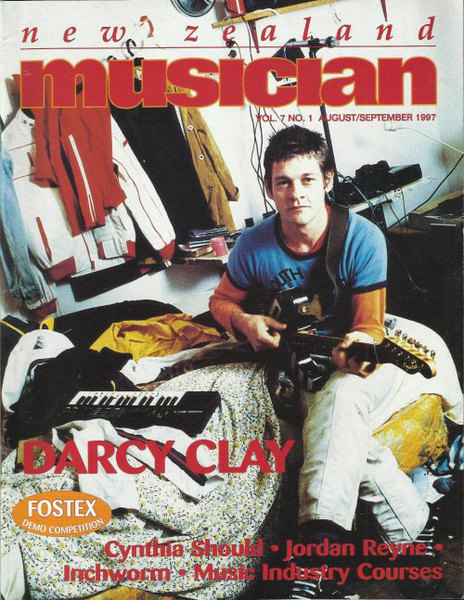

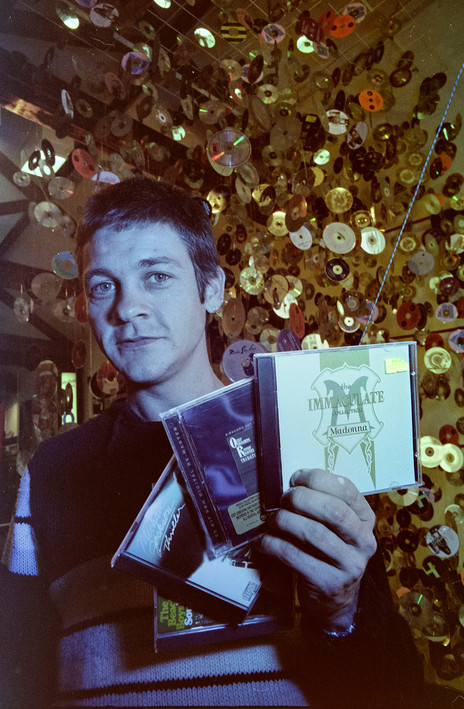

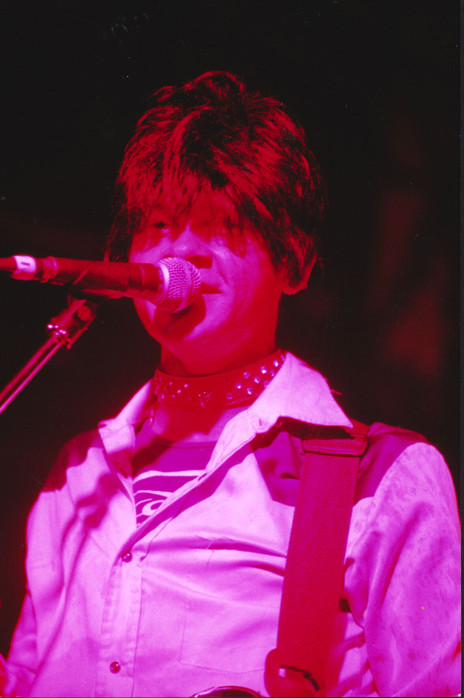

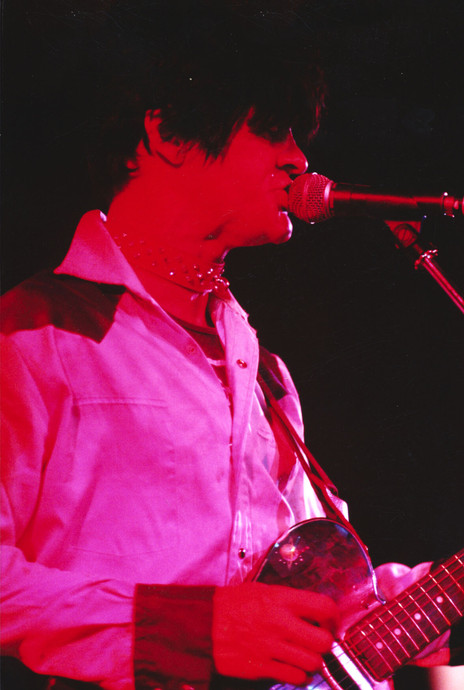

The fallout was beautiful. Put on the hot seat for Havoc’s first showing on TVNZ’s fleeting experiment with MTV, splashed across the cover of NZ Musician magazine, in-store signings in the capital, airtime on major radio stations throughout the country: all the cards were falling in Clay’s favour, culminating in the conceivably daunting task of warming up for one of the most prominent bands on the planet at the time, Blur. For this and other gigs, Clay was backed by a live band, with Joel Tobeck and Bob Kerrigan on guitars and Paul Jett Powers on drums.

Scott Kelly – the man who took up a self-appointed position of camera operator that October evening – tells of Clay's concern about putting on a clinical performance before his biggest audience to date.

"We didn’t know he was going to do ‘English Rose’ until an hour or so before the concert began," says Kelly, "He just decided he’d do it. I don’t even think he had a keyboard, so his girlfriend went home to pick one up. I think the sound guys at the venue got a bit annoyed as they hadn’t sound-checked a stage piano. It all seemed a bit disorganised, but none of this seemed to bother him."

After the biggest show of the most exceptional year of his life, Darcy Clay decided to recede back into his shell for the next five months. Perhaps starting to feel the burn of the limelight, the cracks in his personality that had been papered over with throwaway humour, grand plans and drugs became unmanageable, culminating in his decision to commit suicide at the home of his girlfriend. He was 25.

To the end, Clay kept his concerns to himself, even confiding in Trevor Reekie the night before about what he planned to wear for the upcoming NZ Music Awards, where he was to posthumously win Most Promising Male Vocalist of 1998.

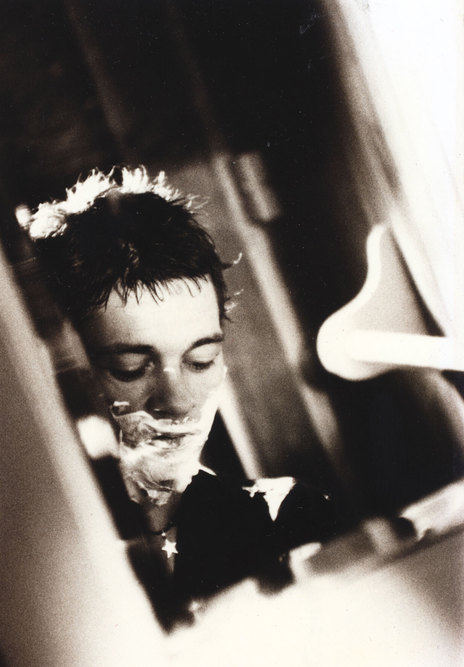

"No one saw anything coming," says Reekie. "Nobody did. It just happened, and his record was very similar in many respects, we didn’t see it coming. He was very different, you know. He came across very, very different. He didn’t dress like other people. He didn’t look like a heavy metal kid, he didn’t look like a glam rocker, he didn’t look like a punk. He just looked like a … guy, in this crazy sort of white suit that he used to wear. He had something that was one out of the box."

At the very end of his raucous ‘All I Gotta Do’, Darcy Clay asked "Will you still remember me, baby?" in an Elvis parody worthy of Las Vegas. It doesn’t matter how many years come to pass. For those who knew him, saw him or listened to what he gave, he will be impossible to forget.

–

The Jesus I Was Evil EP was released for the first time on vinyl by Real Groovy Records on 21 November, 2015. It was limited to 500 copies.