When the classic Dragon line-up of Marc and Todd Hunter, Robert Taylor, Paul Hewson and Kerry Jacobson reunited in 1982 it was with the intention of clearing debts from the decade before. But a hit song with lyrics that grew from a children’s nursery rhyme, and the following album and tour, had them again scaling the highest reaches of the Australian charts.

Dragon sacked Marc Hunter at the start of 1979 and limped on until the end of the year.

Dragon sacked Marc Hunter at the start of 1979 and limped on until the end of the year before disbanding, owing tens of thousands of dollars to various production companies, travel agencies and other businesses. The Hunter brothers in particular were growing very tired of hearing, “Where’s our money?”

The band attended a meeting at Todd Hunter’s Bondi apartment with Marc’s manager, Steve White, and a reunion tour of Australia was mooted which would see the group make enough money to wipe the slate clean. White, who had managed Marc Hunter for a couple of years by then, had got into his charge’s head that the re-formation was the quickest and easiest way to stave off the creditors.

Class Reunion

White quickly got to organising the four-week tour, dubbed Class Reunion. There was no shortage of venues lining up to host the legendary line-up, starting with Sydney’s Sundowner Hotel in the second week of August 1982.

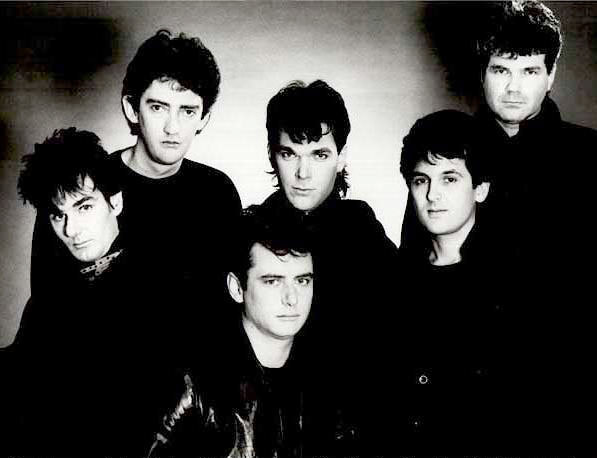

Dragon around the time of the Class Reunion Tour, 1982: Marc Hunter, Todd Hunter, Kerry Jacobson, Robert Taylor (front) and Paul Hewson (rear). - Murray Cammick Collection

At such an early juncture, with the four weeks turning into months, White and the band decided it would be beneficial to have a single out to complement the reunion. The band demoed several songs but it was Paul Hewson’s ‘Ramona’ that won out.

They spent as little money as possible, settling on recording ‘Ramona’ themselves in one day in a little studio in Oxford Street. With Todd mostly taking the production reins, the song was heavy with Paul’s synthesiser hooks and featured saxophone.

White began shopping the tape to the record companies, finding a kindred spirit in the shape of EMI general manager Peter Dawkins. Dawkins had signed Dragon to CBS in 1976 and produced their 1970s hits.

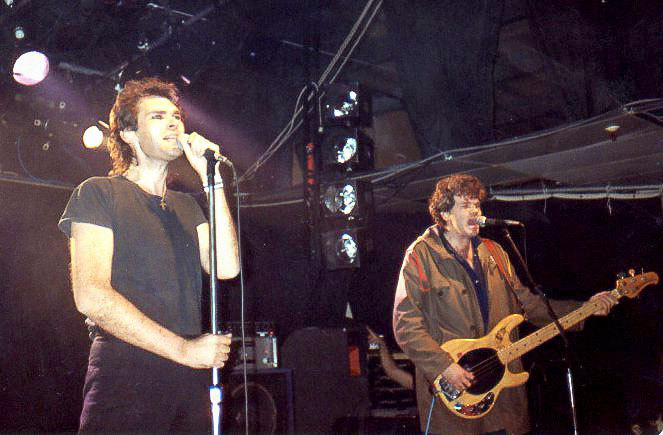

Marc and Todd Hunter, the Class Reunion tour in Hamilton, September 1982 - Photo by Ben Gilgen

But when White turned up at his new headquarters with a re-formed Dragon single, the decision wasn’t as clear-cut as might be expected. Dawkins knew the band intimately and doubted whether the magic of 1978 was still around four years later.

He caught one of the initial Class Reunion shows and was surprised how great the band sounded. Although the guys knew their former mentor was in the room there was no social chitchat, it was definitely a case of “managers at 50 paces”.

Dawkins saw the potential there and agreed to lease the ‘Ramona’ tape and put it out as a single. Although he felt the song was a weak one – in the same basket as Paul’s ‘Konkaroo’, which he himself had produced in 1977 – he felt the band still had the ability to deliver with a comeback album.

With EMI on board, Dragon set off to North Queensland for a run of Class Reunion dates. The attitude was positive and the gigs reflected that feeling. Basically a greatest hits show, the yet-to-be-released ‘Ramona’ had been introduced into the set list and was getting a polite reception from the rowdy sell-out audiences.

Trevor Lucas

It was into this scene that record producer Trevor Lucas was introduced. EMI suggested him as the man to helm a new Dragon album, and Dawkins sent him to the Gold Coast for a bonding session with the boys.

It didn’t take long for Marc and Paul to revel in their returned glory and the industry was soon rife with stories of Dragon’s decadence and debauchery.

Melbourne-born, Lucas moved to England in the 1960s where he fell in love with and eventually married Fairport Convention singer Sandy Denny before joining her band. When Denny died after a fall down a flight of stairs in 1978, Lucas and their baby daughter returned to Australia. Back home he had produced tracks by Goanna and Paul Kelly & the Dots before coming into contact with Dragon.

As soon as Dragon hit the familiar territories of Sydney and Melbourne, the group’s condition deteriorated. It didn’t take long for Marc and Paul to revel in their returned glory and the industry was soon rife with stories of Dragon’s decadence and debauchery.

Before work could start on an album, however, the Class Reunion tour pressed on with three gigs in New Zealand in September. The support act for the shows were the Legionnaires, featuring three members of Dragon’s sister band from NZ, Hello Sailor.

The omens weren’t good when EMI released ‘Ramona’ in the week before Christmas. Without a big push from the record company or radio support, the track stalled at No.79 in the Australian singles chart before dropping out.

Nevertheless, Dragon convened with Trevor Lucas to begin work on their comeback LP. After Lucas spent the entire day trying to get a decent bass drum sound, which included experimenting with stuffing toilet paper inside it, Dragon realised the liaison was not going to work and complained bitterly to Peter Dawkins.

With the failure of ‘Ramona’ fresh on his mind, Dawkins cancelled the sessions, giving Lucas a $10,000 payout, and cut his ties with Dragon. The stories of Marc and Paul’s partying had reached his ears and he concluded there was probably too much water under the bridge to result in any future triumphs.

Dragon’s debt was by now well paid off, but there was no intention of letting up. The EMI disappointment behind them, the plan now was to secure a contract for a comeback album. With Marc’s solo career being overtaken by the band’s, his label shrewdly concluded they should snare the band as well.

Over to PolyGram

Marc had been with PolyGram since the release of 1981’s Big City Talk LP on its subsidiary Mercury label. When PolyGram A&R director Michael Crawley happened by EMI’s Studios 301 while Dragon were demoing a new song called ‘Rain’, he burst in, declaring, “That’s the best song I’ve heard in my life,” and convinced the band to sign with the label.

But persuading the rest of PolyGram that Dragon was a good investment was a different story. Crawley’s biggest hurdle was the company’s new managing director, South African Bruce MacKenzie, who knew nothing of the band’s previous chart success but plenty about their involvement in the drug underworld, thanks to The Royal Commission of Inquiry Into Drug Trafficking Report released earlier in the year.

The joint Federal, New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria inquiry stated that Donna Shaw, a former girlfriend of then drummer Neil Storey, revealed to police “the entire band was being supported by the sale of heroin” in the mid-1970s and that “Paul Hewson was also selling a lot for (Greg) Ollard”, an associate of Mr Asia syndicate boss Terry Clark.

Steve White and Dragon decided not to issue any statement or defence against the allegations in the report. The band members were struggling to even place a Donna Shaw in their circle at that time, let alone as a girlfriend of their late drummer. Crawley fought tooth and nail and eventually convinced MacKenzie Dragon was worth the trouble.

Rain and Alan Mansfield

Todd had written the bulk of ‘Rain’ at his Bondi home and it had been kicked around in various practices and home demos. During a nighttime session, Todd’s partner Johanna Pigott jokingly sung the children’s rhyme “It’s raining, it’s pouring” over the yet unnamed instrumental track and the lyrical concept was born.

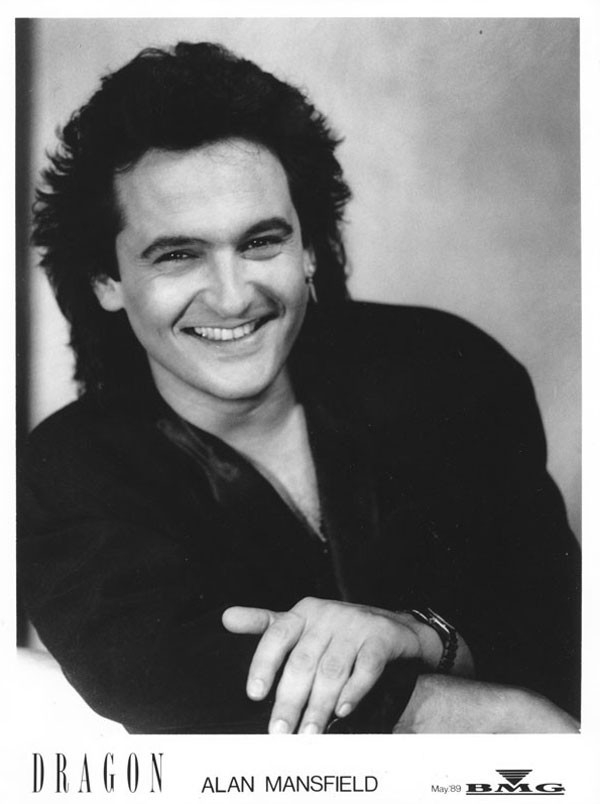

Studio time was booked to record ‘Rain’ and the band opted for “American in town” Alan Mansfield to produce.

Studio time was booked to record ‘Rain’ and the band opted for “American in town” Alan Mansfield to produce. A graduate of the Boston Conservatory of Music, Alan came to Sydney with Bette Midler’s band in 1979, “dug the place” and spent some time in the city producing and playing keyboards and guitar in various sessions, when he wasn’t touring the world with English blue-eyed soul singer Robert Palmer.

He was co-producing a Doug Parkinson album when he first encountered the towering Marc Hunter, who suggested Alan come over and do some work on his new album. Marc was immediately captivated by the American’s supreme assuredness and the street cred his Palmer association brought.

With the Dragon reunion in full swing, Marc introduced Alan to the rest of the band and they too were impressed. And he came with no preconceived ideas, as he had no awareness of the band whatsoever, a fact the band embraced.

‘Rain’ was a bit of a departure for Dragon. It owed more to the current new wave sounds with its throbbing bass line than any connection with the band’s back catalogue. Todd was leading the band into new territory although most of them were unsure how it would be received.

On the day of the session at Rhinoceros Studios, Kerry Jacobson turned up with a bad headache – the last thing he felt like doing was playing the drums. He took some Panadeine and settled in for a long day behind the kit.

In the control room, Alan was blown away when the band nailed the backing track on the third take. Todd, Robert and Kerry laid down an aggressive bed to which overdubs could be added and, mercifully, Kerry could go home.

Alan, who had played a big part in the arrangement of ‘Rain’, left Todd, Marc and Johanna to complete the lyrics in the verses while he recorded Paul’s low, menacing synthesiser parts. Although Paul was present, he had no inclination to join in on the writing. Alan then played a guitar solo on the outro of the song, which Robert later replaced.

The original video for ‘Rain’ featured a cameo from Marc Hunter’s son Titus. When PolyGram International released the song in the US, they made a second video – featuring new members Terry Chambers and Alan Mansfield and a post-apocalyptic scenario – which the band vetoed, causing a third video to be filmed.

That night, as Alan, White and the Hunters listened to what had been achieved, they agreed the song had No.1 written all over it. “If this song doesn’t make it to number one you’ll have to join the band,” the boys baited Alan.

Michael Crawley arrived at the weekly PolyGram management meeting barely able to contain himself, a tape of the completed ‘Rain’ under his arm. After sitting through its entirety, the national sales manager commented dully, “The guitar needs to be a bit louder.”

The next week, Crawley attended with the unchanged song pressed onto a 45rpm acetate. “Oh, yeah, you’ve fixed it. It sounds better, but I don’t know if it’s a hit,” the national sales manager moaned.

Week number three and Crawley turned up with the again unchanged song, this time accompanied by a video featuring a cameo appearance from Marc’s son, Titus, crouched beneath Paul’s keyboard stand. “Oh, yes, that’s a hit!” said the national sales manager. Crawley just rolled his eyes.

‘Rain’ was released on August 15, 1983, and began its rise to the top. But camped in the No.1 spot and unwilling to budge for a bunch of expat New Zealanders was a novelty single called ‘Australiana’ performed by comedian Austen Tayshus. Dragon had to be content with No.2.

The short-lived five-piece Dragon just prior to Alan Mansfield joining, 1983. Left to right, Robert Taylor, Terry Chambers, Todd Hunter, Marc Hunter, Paul Hewson.

Drummer required

On the road at the start of September, Kerry Jacobson was opening a bottle of beer post-gig on a wall opener in his hotel room when the neck broke off and cut his right index finger. He was rushed to hospital for stitches.

In the morning, the band drove to their next gig where Kerry played the drums with just his left hand. It was a ridiculous situation – Australia’s top band of the moment with a one-handed drummer and a pianist who more often than not lay on the floor between songs to ease his back pain – and it was clear that they would have to find a fill-in drummer for the next two weeks.

With ‘Rain’ in the Top 10 it was important to keep the impetus going, and White immediately contacted Angels drummer Brent Eccles.

With ‘Rain’ in the Top 10 it was important to keep the impetus going, and White immediately contacted Angels drummer Brent Eccles. Another New Zealander, Brent had come to Sydney with Citizen Band in 1979. They struggled for more than a year and when the drum stool became vacant in The Angels in March 1981, Brent successfully auditioned.

White approached Brent to see if he was free for a week’s work in Sydney and a week in Melbourne. The Angels weren’t working at the time and Brent agreed, learning the intricacies of the Dragon material from a cassette. He was familiar with the songs and looking forward to playing with the band.

A rehearsal was called before the run and when Marc didn’t show up Paul sang all the songs. The drummer was a fine fit but was nervous for his debut at the Doyalson RSL. Until, that is, Paul lay down under the piano and played it with one hand. Brent relaxed and enjoyed himself after that.

Meanwhile, Kerry Jacobson was in a bad way. His cut finger was just the tip of the iceberg. He went up to Newcastle to stay with his mum while his injury recovered and suddenly realised he didn’t want to go back.

He wasn’t travelling well. Dragon was just a platform for him to leap off, what with trying to keep up with Paul and Marc. He knew things would get worse if he returned, and he rang Steve White and said he wouldn’t be back. Kerry never spoke to any of his band mates and they made no attempt to contact him when they received the news.

Dragon's Body And The Beat line-up: Terry Chambers, Marc Hunter (rear), Alan Mansfield (front), Todd Hunter, Paul Hewson (front) and Robert Taylor (rear)

Brent Eccles was never a consideration to take his place permanently – he was well entrenched in The Angels set-up – but as the fortnight was coming to an end he mentioned that former XTC drummer Terry Chambers had moved to Australia and was living at his in-laws’ in Lake Macquarie.

Todd’s ears immediately pricked up. He had been a fan of the English band XTC, and in particular their drum sound, for several years and could not believe Terry had been sitting around in Lake Macquarie for a year.

Of more pressing concern, though, was the fact that studio time was booked with producer Alan Mansfield to record ‘Magic’, the follow-up to ‘Rain’, and Dragon were without a drummer. The band had to use the time and roped in top session player and original Spectrum drummer Mark Kennedy to overdub drums to a pre-recorded click track.

Alan Mansfield

Robert Taylor wrote the chorus of ‘Magic’ before joining Dragon in 1975. Not long before the Class Reunion gigs eight years later, he wrote the first verse to another song, but with Todd demanding the band come up with new material the two songs were put together and Marc completed the lyrics.

The next order of business was an audition for Terry Chambers. Terry had joined the band that would become XTC in 1973 and they were signed to Virgin Records in 1977. His drumming came to the fore with XTC’s Drums and Wires LP and its big hit ‘Making Plans For Nigel’ in 1979. They enjoyed one more top 10 hit with ‘Senses Working Overtime’ in 1982 before guitarist Andy Partridge called an end to the band’s touring days and Terry consequently handed in his notice.

Dragon's 1984 Body And The Beat album, with a sleeve designed by Kate Hepburn

Terry and his Australian wife, who had found it difficult adjusting to life in England, moved to Australia to live with her family in Lake Macquarie. Terry was at a crossroads in his career and although he intended to continue playing he had just two Australian contacts – Angels manager John Woodruff and Icehouse manager Ray Hearn.

His first opportunity came when Ray organised for Terry to come to Sydney to meet up with Deckchairs Overboard, whose drummer, Paul Hester, had just left to join Split Enz. Terry made the trip but wasn’t interested in their material and refused the offer.

It was abundantly clear that Terry’s powerful, frenetic, hard-hitting style was poles apart from Kerry’s natural swing.

Ray next suggested Dragon. Terry hadn’t played for about 18 months but ventured to Sydney again to try out. He bashed around on a borrowed kit and was offered a retainer of around $800 a week, about twice the average weekly wage, to take the job.

Dragon had their new drummer but as rehearsals progressed for the next run of live dates trouble reared its head. It was abundantly clear that Terry’s powerful, frenetic, hard-hitting style was poles apart from Kerry’s natural swing and lazy South Pacific funk on which the band had built its success.

The more Terry tried to bring the classic songs into the 1980s, the more Marc came down on him. “But this is how people want to hear it,” he’d chide the new recruit. The intense two weeks of rehearsal was like joining a covers act for the man once part of one of England’s most lauded, original bands.

One of the two planes Dragon leased for the Body And The Beat tour in 1984. Dragon flew in one while support act Sharon O’Neill and her band took the other. Pilot (left) and crewmember unknown - Photo by Colin Baldwin

Enter Carey Taylor

Meanwhile, PolyGram had enlisted the services of Englishman Carey Taylor to mix the ‘Magic’ single in London. Earlier in 1983, Carey produced and engineered Cut the Talking, an album by The Dugites, for PolyGram Australia. He was recommended to Michael Crawley by fellow English producer/engineer Nick Launay, who was achieving chart success with Midnight Oil.

Carey had started working as a freelance assistant engineer in English studios in 1979 and was soon working on recordings by acts as diverse as Marvin Gaye, Duran Duran, Iron Maiden and Carlene Carter. By 1981 he was engineering full-time for Welsh rock’n’roll revivalist Dave Edmunds. Together they recorded tracks for The Stray Cats, George Thorogood & the Destroyers and Edmunds himself.

Until producing The Dugites album, Carey’s production experience had been restricted to a few singles by minor UK artists, but he had gained a lot of experience in new and innovative recording techniques, including sampling, Fairlight digital components and drum machines.

During the recording of The Dugites album in Melbourne, PolyGram had asked Carey to mix the Alan Mansfield-produced ‘Rain’, which he loved. The results were well received by the company and Dragon. Back in London he mixed Alan’s production of ‘Magic’, adding a couple of overdubs.

Once again, PolyGram were delighted with the results and Crawley asked Carey to produce the new Dragon album. The A&R man dispatched some demos and some of the band’s previous albums along with the puzzling description that they were “a sort of Australian Rolling Stones”.

On the eve of the first sessions for the new record there was another significant change in the Dragon line-up. Following the throwaway invitation to join the band should ‘Rain’ not hit the top spot in the chart, Alan Mansfield was now an official member on keyboards and guitar. With all and sundry in the music industry warning him against the move with tales of Dragon’s wickedness, Alan couldn’t resist.

The new songs written for the album contained more keyboard and guitar parts than their 1970s equivalent and the addition of Alan, accomplished on both instruments, was logical to Todd and Marc, who had written the bulk of the material. Paul Hewson had offered no new material.

The tone was set by Marc’s memorable and sarcastic greeting, “So, you’re the young whippersnapper they’ve sent to produce our album!”

It was a nervous and jet-lagged Carey Taylor who met Dragon rehearsing in the basement of the Sydney Opera House. The tone was set by Marc’s memorable and sarcastic greeting, “So, you’re the young whippersnapper they’ve sent to produce our album!” It was 30-year-old Marc’s way of showing the 26-year-old producer who was boss.

New to the band, Carey surmised the leadership fell on the Hunter-Hunter-Mansfield axis. He recognised Alan was a big presence in the band with a strength of personality to match Marc and Todd and he had the kudos of producing their comeback hit, not to mention his exceptional keyboards skills.

Hoping to capture the qualities of ‘Rain’, Dragon set up for live backing tracks at Paradise Studios in Woolloomooloo, Sydney, with Paul on Hammond organ and Alan on synthesiser. However, these early sessions did not go well, largely because Terry Chambers did not bring the fluid rhythmic ease that Kerry Jacobson had brought to ‘Rain’ and Mark Kennedy to ‘Magic’.

Disappointed by the stiff results, the idea of capturing the band live receded as an option and recording commenced in a more layered fashion starting with drum machine and bass, examining each performance as it went down, and recording real drums later.

Blowing the budget

Michael Crawley was ambitious for the album to be internationally successful and Carey was given an initial budget of around $70,000. Dragon’s deal with PolyGram was for a comparatively low royalty rate with non-recoupable recording costs, compared to the international norm of a higher royalty with recording costs recouped.

Hence, there was no incentive for the band or producer to save money or deliver anything but the best album possible, regardless of cost, and the budget was quickly blown. Crawley was summoned to finance director Michael Smellie’s office almost weekly where he was asked, “What are we gonna do about this?” Another budget was set that was just as swiftly blown.

The Body and the Beat line-up of Dragon: Paul Hewson, Robert Taylor, Terry Chambers (front), Marc Hunter, Alan Mansfield and Todd Hunter

Given a free rein, Carey and the band tried a lot of things that they decided weren’t good enough for the final album, including a couple of days just recording snare drum samples in every area of Paradise to add in behind the live drums to fatten up their sound.

It got to the point where Smellie would turn up at the studio for an hour on a regular basis to see where all “his” money was going. On these visits, Carey and the band would show him just enough – a new song, a new guitar track – to have him think the money was well spent.

The entire company believed in Dragon creatively, but Smellie doubted they could do it within a timeframe that would make financial sense. In hundreds of discussions with Crawley, the band’s champion, Smellie the skeptic was dragged around to the view that it was best to push on and adjust the budget again. When Smellie left to work in Brazil late in 1983, the budget had ballooned over $220,000.

Completing Body and the Beat

With the tracks nearing completion, recording was put on hold for a Christmas break before recommencing in London in February with the arrival of Marc, Todd and Alan. The main reason for reconvening in London was the ability to mix on SSL recording consoles with complete automation. Some of the tracks had so many recorded parts that they had to be mixed in sections.

Recording and mixing was completed in Sarm West, Maison Rouge and Pete Townshend’s Eel Pie studios, with brief stints at the Townhouse, RG Jones and Trident, depending on availability. As a freelance assistant having worked in the same studios, Carey Taylor was confident and knowledgeable in them all.

Drum tracks on ‘Cry’ and ‘What Am I Gonna Do?’ were replaced in London by Tony Visconti protégé Andy Duncan, who also created the abstract percussion break in ‘Wilderworld’ by sliding film cans around the floor of the live room in Maison Rouge.

It was a battle of wits between Carey and the famously difficult-to-record Marc.

The ‘Body and the Beat’ arrangement was influenced by Yes’s November 1983 US No.1, ‘Owner Of A Lonely Heart’. Carey was intrigued by the total shifts in style and tone throughout the Yes song and was hunting for drama and extreme production values for the Dragon project. ‘Body and the Beat’ was heavily developed and arranged by Todd and Carey with some drastic changes from section to section.

The Hunters recorded virtually all the vocals on the album, with a few chorus additions from Alan and some remaining from the Sydney sessions from Robert Taylor. It was a battle of wits between Carey and the famously difficult-to-record Marc, because the producer wouldn’t let Marc bully him into accepting anything less than perfection.

A mutual admiration grew between the pair – Carey loved the singer’s voice while Marc grew to respect Carey’s stubbornness in standing up to him and making him work until he’d delivered to his full potential.

Once the lead vocals were complete, Marc was the first to return to Australia, followed by Alan, having overdubbed more keyboards, some chunky guitar power chords and a couple of guitar solos. Session players also added guitar parts.

Todd was Carey’s rock throughout, laying down all the great bass guitar parts, solely recording many layered harmony vocals and providing much appreciated emotional support. He was the last to return home, in March.

Even with the band back in Australia, Carey wasn’t finished. The horn section from Graham Parker and The Rumour added some real brass while Simon Darlow, of the revamped Buggles, added some grand piano power chords and a couple of texture pads to ‘Cool Down’ as well as the album intro to ‘Rain’.

Then the producer buckled down to the arduous task of mixing the album alone, spending a day or more on each track, with one or two tracks mixed twice after unsatisfactory initial attempts. He even tried to remix ‘Rain’ but couldn’t better his original Australian mix, which was eventually “stitched on” to the new Darlow intro.

Carey Taylor was so exhausted by the time he had completed the project in April, after around six months of six or seven long days’ work and approximately A$400,000, and he hadn’t even a clue of its hit potential. One thing was for certain, the enormous budget blow-out cost Michael Crawley his job.

The strengths of the album were the Hunters, with big assistance from Alan Mansfield, but the production greatly overshadowed the band. The contributions of Paul Hewson, Robert Taylor and Terry Chambers were greatly diluted. Carey felt the replacement or addition of parts were never a question of the trio not being up to standard but rather a reflection of the production ambitions for the project.

The extravagant self-indulgence of planes, limousines, separate hotel rooms and huge alcohol riders meant there was very little money left for the band.

With just his second full album production, Carey was eager to make his mark with a unique piece of work and felt some of the textures and sounds he was seeking were never going to come from Paul and Robert’s more conventional range of sounds. Likewise, Terry’s regimented, admired work with XTC did not translate to Carey’s dynamic vision for Dragon.

Alan recorded most of the keyboards in Sydney and London, including the dramatic piano opening to ‘Cry’. Only a couple of Paul’s Hammond organ and piano parts survived.

With the album, now titled Body and the Beat, due for a mid-June release, the band was called together to start rehearsals in Sydney for an ambitious tour of entertainment centres and larger clubs.

Robert bought a whole raft of effects pedals to copy the album’s guitar sounds and set about learning the parts. Alan would play second guitar or Syndrums on the old songs and keyboards on most of the Body and the Beat material.

The Dragon line-up that toured Body And The Beat. Left to right, Robert Taylor, Todd Hunter, Alan Mansfield, Terry Chambers, Marc Hunter, Paul Hewson.

Marc continued pressuring Terry Chambers about the older Dragon songs, which, in regards to ‘Still in Love With You’ and ‘Are You Old Enough’, were sped up considerably or, as with ‘April Sun in Cuba’, beefed up with Alan’s Syndrums. The old argument of “But this is how people want to hear it” was no longer valid.

The tour roared through Adelaide, Tasmania, Melbourne, Sydney, provincial New South Wales, the Gold Coast, Cairns and Brisbane, virtually selling out everywhere, and the show at the Sydney Entertainment Centre on August 10 was filmed and recorded for later release.

The Body and the Beat tour wound down with Terry being let go in October. It was an uneasy fit from day one with Terry’s unassuming, quiet personality at odds with the others’ gregariousness, and he certainly never got the band’s cynical sense of humour. It came as a relief when Marc told him he wasn’t the right man for the job.

The rest of the band attended a series of business meetings with manager Steve White in which he revealed that although the tour had grossed more than half a million dollars and sold out all manner of venues, the extravagant self-indulgence of planes, limousines, separate hotel rooms and huge alcohol riders meant there was very little money left for the band.

Ironically, the only band member to make any money out of the exercise was Terry Chambers on his $800 a week wage. The band was flabbergasted. They had just experienced their greatest success and were left with little to show for it.

By the time Live One, the album from the Sydney show, was released in June 1985, Paul Hewson was dead from a drug overdose, Robert Taylor had been sacked and the Hunter brothers were the only remaining link to Dragon’s New Zealand past.