On Matakana Island, Māori was the first language, he recalled to Suzanne Ormsby in 1995. “While we spoke English at school, when we arrived home, our grandparents and parents spoke to us in te reo Māori. I am fluent in te reo simply because I learnt off my kaumatua and pakeke on the marae and throughout the home environment, where Māori was always spoken.”

The family was deeply musical. Ben’s upbringing was described by Karl Steven: “His grandfather played for the celebrated Rātana Brass Band, and his uncles were all keen guitarists, gigging regularly around the region with their band The Beachcombers. These were pioneering days, and Ben’s uncles would make their own steel guitars out of fence posts, carving them, installing the pickups from telephone receivers, and amplifying them using a Gulbransen radio loaned from one of the island’s elderly residents.”

At primary school, during the Second World War, Ben played in The Beachcombers performing at patriotic dances for New Zealand soldiers overseas, and the Home Guard. “I was playing steel guitar and my brothers were on rhythm guitar, ukuleles and playing peach leaves as clarinets. We had to ad lib our way through music. Then I heard a guy, Keith Branch, who put ‘Pōkarekare’ in the tempo it’s in today. I fell in love with his style of playing and I nurtured and followed that style. These days I am close to the [Hawaiian] styles of guys like Dick Mclntire, Gerry Byrd, Al Kealoha Perry, Lani McIntire and many others.”

During the 1940s, he became a gigging musician, performing popular Māori songs in the Hawaiian style at dances from Whakatāne to Paeroa.

In 1947, aged 13, Ben went to St Stephens College at Bombay, south of Auckland. Much of it was alien: he had never used a toothbrush, switched on an electric light, and very rarely wore shoes. He was homesick, but made close friends and learnt good values.

Crucially, he kept speaking Māori at St Stephens, “not knowing that one day it was going to be essential to my future. In Auckland I’ve been involved in the taha Māori, marae, kaumatua, pakeke, the justice system, the social welfare system, which my language te reo Māori, tino rangatiratanga has helped me along.”

At the Maori Community Centre, Tawhiti picked up a guitar and someone said “Oh, come and back me on a song”.

After finishing school he briefly worked at the Martha Goldmine in Waihi, before moving to Auckland in 1950. “I went to Elam School of Art for a time and did some art work. I also met up with a good friend of mine there, [Māori artist] Arnold Wilson. But abstract painting was not for me, so I went and worked on the tramlines in Auckland and it was there that I heard about the Māori Community Centre and all it had to offer in terms of Māori gatherings and entertainment. I breezed along there on a Friday night, Saturday night and Sunday night, and I picked up a guitar and someone said ‘Oh come and back me on a song’. It was only a three-chord song and so I did. It was from then on that my musical ability blossomed.

“At the time I was at the Māori Community Centre, the groups there were fantastic. There were a lot of vocal groups and of course one that caught the attention of the entrepreneurs of the day [Harry M. Miller and Graham Dent] was the Howard Morrison Quartet.”

Ben stopped playing steel guitar, and picked up an electric, performing at Auckland venues such as The Oriental, St Seps, The Crystal Palace, and The Māori Community Centre. “I played with many guys and overseas artists as well. We toured with Gene Pitney and Jean-Claude Pascal and many top New Zealand shows.”

In the late 1950s, Ben rehearsed with the Māori Hi-Five before they left to go overseas. He remembers that at the final rehearsal his oldest daughter Raewyn asked, “‘Where are you going Dad?’ I looked at her and I could see the look in her eyes and that hit me in my soul and I said, ‘Hey I’m not leaving my kids.’ I rang Jim Anderson, who was our manager, and told him I wished to be left behind. Paddy-wack Te Tai took my place in the band and I stayed behind with my family.” (Ben and his wife Ellen would eventually bring up nine “wonderful” children, and have 13 mokopuna. “That makes me a very proud grandfather.”)

Because of his musical ability, Ben went “to a lot of Māori meetings and that started my community involvement with Māori Affairs. I became involved in the Māori Wardens. Some people may not be aware that the real Māori Community Centre was just below where the university marae is now [between Symonds and Stanley streets]. They had accommodation where people travelling north or south could stay. It was a stop-over place. There were rooms with cooking conveniences and all the Māori gathered there.”

What Ben describes as “the other Māori Community Centre” was the legendary hall on the corner of Fanshawe and Halsey streets opposite Victoria Park. It was a meeting place for urban Māori, an entertainment centre, and a base for many Māori sports clubs, which practised on the park. “The Māori Community Centre used to run from Wednesday through to Sunday night and there were activities galore. People would come from miles away just to be there.”

The centre held regular talent quests, and many professionals performed or socialised there as well. Among the artists he remembered at the MCC were Kiri Te Kanawa, Hana Tatana, The Pleasers, many opera singers of the era, and other musicians from throughout New Zealand. Overseas visitors included the Platters and Cole Joy.

“People used to flock [to the park] on a Saturday afternoon or a Sunday and watch sports and go across to the MCC afterwards for a feed. There were no bars where only Māori performed, we had Pākehā entertainment too. It was ‘standing room’ only down there at that time. It was a place that, when you walked in, there was wairua there and also the Rātana faith had a stronghold down there.”

“you could walk from Fanshawe Street to Point Chev with your girlfriend and no one would harass you.”

For men, the fashion craze was for “zoot suits”: stove-pipe trousers, and broad-shouldered jackets. “When those guy took their clothes off, they looked anorexic!”

In the 1950s and early 60s, “Work was a-plenty in those days and if you weren’t working you were bloomin’ lazy. You could finish your job and work nights if you wanted to. Seagulling on the wharf and of course the tramlines. The freezing works helped a lot of people and that closure sort of took a lot of people down. In those days of course you could walk from Fanshawe Street to Point Chev with your girlfriend and no one would harass you. There were so many dances on at the time. You just poked your head in and if you didn’t like the music, you went to another one. The Manchester, Trades Hall, Catholic Social Centre, the Metropole, the Playhouse, the Oriental, St Seps. Yes, that was the entertainment scene of that time.”

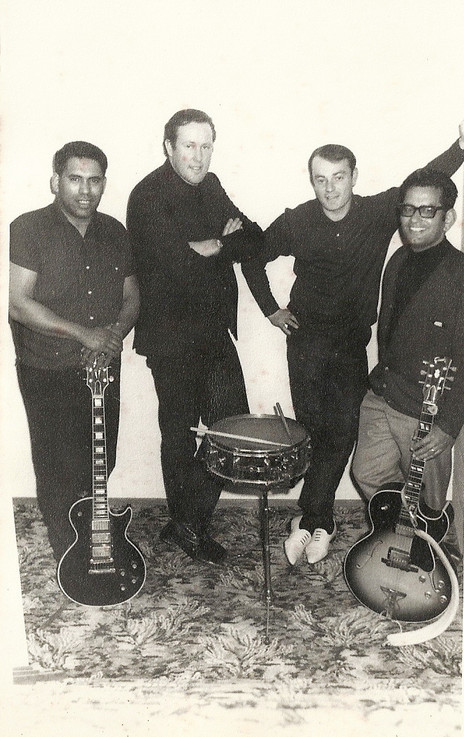

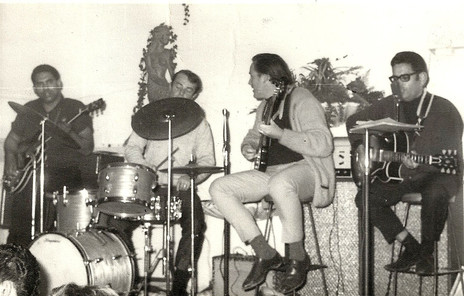

Ben had a stint playing with Bill Sevesi and his Islanders at the Orange Ballroom from the late 50s and played on Zodiac recording sessions by acts such as Eddie Howell (‘Hippy Hippy Shake’), the Silhouettes (‘My Tani’), with the Matonaires (Ben on lead guitar, Buddy Wilson rhythm, Keith Roach on bass, and drummer Alex Behrens). He also recorded with teenage guitar instrumentalist Gary Bayer (‘Cactus Hop’).

Later in the decade Ben performed in Tahiti with George Tumahai, Billy Nuku “and the boys from Whakatāne, Nuki and Gugi Waaka. We had a great group across there. We played a lot of Pacific Island music and modern music and when we came back, we made the album Welcome To Tahiti [by Nat Mara, on Viking].”

Ben toured the Pacific with French comedian and singer Jean-Claude Pascal and a 16-piece orchestra, only to find the French organisers had disappeared when it came time to get paid. “We missed out quite badly there.” A newspaper headlined a story about the incident, “Musicians Looking for Lost Notes.”

At a Papatoetoe Town Hall dance – so packed that people who couldn’t get in stood outside and listened – Phil Warren asked Ben if he would like to play at the Oriental Ballroom, on Symonds St in the city. “I thought, why not? We were sick of drinking cocoa and having madeira cake for supper, so we moved into the Oriental Ballroom and we started packing them in there.

“One particular night I remember well was the night I got electrocuted. I was moving the microphone to John Stowers who was playing piano and I had the sensation of falling slowly down on the stage and things were ringing and bright lights. But to the guys who saw me I just shot across the stage and John, who was sitting there playing away, looked around and saw me flying past. Luckily the rhythm guitarist kicked the plug out of the wall. They said I must have had about eight and a half seconds of electricity going through me at the time. Of course I was out to it.

“The music stopped and the stage was full of people. ‘I’m a doctor, I’m a nurse.’ Everyone was jumping up on stage. The ambulance came and took me to hospital and checked me out. I was okay, just a bit groggy. They advised me to go straight back to the hall after having a bit of a sleep. They said I had to face it then and there, or I may never have gone back. When the policemen accompanied me back into the hall, everyone stood around and clapped.

“Guess what was in the paper the next day? ‘Band Leader and Guitarist Does the Electric Twist!’”

“Guess what was in the paper the next day? ‘Band leader and guitarist does the electric twist!’”

The Picasso, on Grey’s Avenue, was an underground club that featured many top musicians into the early hours. One memory that always made him smile, he told Suzanne Ormsby, was when “this big Māori man and his son came in and he asked if his boy could sing a song. I refused because of the way the boy was dressed: garberdine coat and sandshoes. It wasn’t until years later that I found out that his boy was John Rowles. So I bite my tongue. However John and I get on very well and he comes over and visits me. Actually my rhythm guitarist Buddy Wilson taught John at primary school. I’ve never forgotten that occasion at the Picasso when John Rowles wanted to sing.”

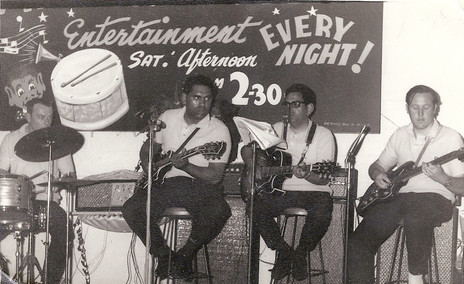

In 1966 he formed the Ben Tawhiti Quartet. In an expansive tribute to Ben, Buddy Wilson recalled “It was at a gig at the Mt Roskill Memorial Hall in 1967, that Matiu Rata, MP for Northern Māori, announced that 10 o’clock closing had been given the green light by Parliament. As well as killing the dance halls, this new law took us off the gig circuit for four years as it was Ben’s reputation which got us an audition at the Milford Marina hotel with publican Bert Mackie, on the first day of 10 o’clock closing. That first night was enough to give us the residency of that pub for the next four years.”

The group expanded and became known as the Mariners Showband, and backed many singers and entertainers, “playing to a packed bar every Saturday at a time when dancing wasn’t allowed,” wrote Wilson. Other members included saxophonist Marsh Cook (formerly with the Quin Tikis), Alex Behrens on drums, and Keith McIntyre on bass. “This gave the band a showband sound and Ben’s harmonies with Marsh had to be heard to be believed.”

Wilson played with Ben for 40 years, and was in awe of his temperament, as many gigs – especially 21st birthdays – ended up in fights. One night at the Milford Marina, though, Ben had enough. When a fight broke out while the band was playing ‘Wheels’, he stopped the fight in his own way. Wilson has a recording of the gig. “You can hear the music stop as Ben dropped his guitar, leapt off the stage, dealt to a couple of the offenders and then calmly walked back to the stage and carried on as though nothing had happened.”

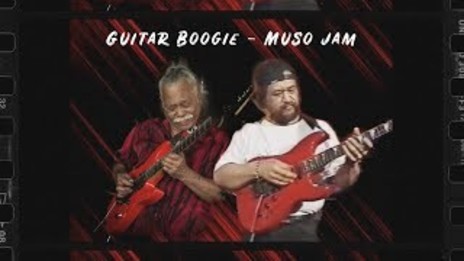

But it was Ben’s musical talents that always impressed Wilson. “I have memories of many would-be guitarists standing and watching Ben play his Gibson Les Paul. Many would have the technical skills, but few if any would have what I call ‘the feel’. The ‘feel’ combining technique with heart or soul and sheer ear. No lead guitarist I have ever played with over the last 45 years, has ever been able to emulate his style of playing.”

“Once we played at a place so small Ben had to stand outside and play” – Buddy wilson

After leaving the Milford Marina in 1971, the band kept playing regularly for another 25 years, playing gigs from Kaitaia to Waiouru, at “every pokey little hall” in Auckland, RSAs, Cossie clubs and rugby clubs, even on a beach at Rangitoto and at Moller’s Farm in Oratia. “Once we played at a place so small that there wasn’t enough room for the band and Ben had to stand outside and play.”

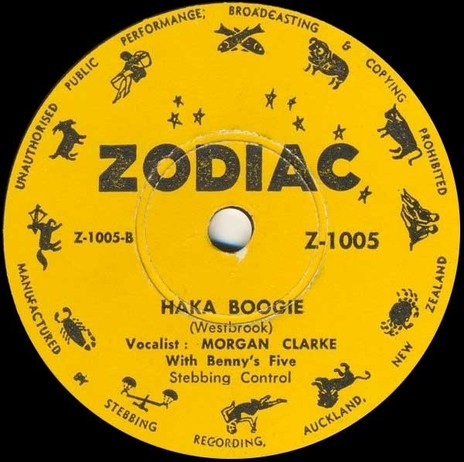

Ben’s most famous recording came in 1957, when his band Benny’s Five backed Morgan Clarke on his Zodiac 78 ‘Hawaiian Boogie’ b/w ‘Haka Boogie’. In 1999, NZ Herald music writers Graham Reid and Russell Baillie wrote a column called “My Top Ten Guitarists”. In the No.1 position was Ben Tawhiti. Their explanation was: “At the one-minute mark of ‘Haka Boogie’ by Morgan Clarke with Benny’s Five, Tawhiti starts a steel guitar solo which, by some mystery of the cosmos, pulled together Hawaiian style and Chet Atkins country. If this had caught on internationally, Tawhiti might have been a bigger influence on George Harrison from the Beatles than Chet Atkins was. Then where would we be?”

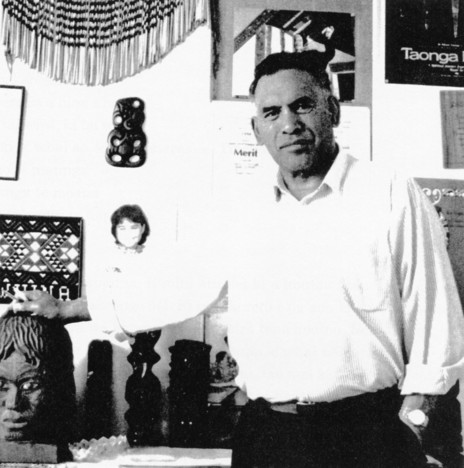

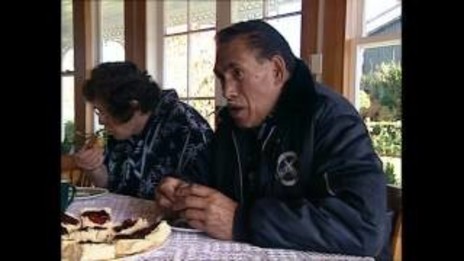

In 1996 Ben he was included in the documentary Ten Guitars, about New Zealand’s alternative national anthem, and in 2003 Waka Huia made an hour-long documentary, Ben Tawhiti – Musician.

After the gigs for his band started slowing down in the 1990s, Ben concentrated on his steel guitar playing – often backing Dennis Marsh. In 2006 he was commissioned by Māori TV to provide the music for Maumahara, a programme in which kaumatua recalled their memories of the 1940s and 50s. The group Ben assembled included Buddy Wilson, Joe Haami (Māori Volcanics), Marsh Cook, drummer Richie Diaz, and Tom Paul on bass. The backing singers were an illustrious lineup: Taisha, Hinewehi Mohi, Mahinaarangi Tocker, Whirimako Black, Dennis Marsh, Manu Harrison, and Mabel Wharekawa Burt.

Ben’s last recording session came when he was in his late 70s. He was asked to create the soundtrack for Nova Paul’s 2010 film This is Not Dying. Among the pieces was the traditional Ngā Puhi ballad ‘Whakarongo Mai’, in response to Nova’s iwi and the film’s location.

In the liner notes to the release of ‘Whakarongo Mai’ as a 7" disc on 1:12 Records, Karl Steven wrote:

The film was played down in four passes as Ben recorded first rhythm, then lead, and then lead harmony on his 1952 Gibson Les Paul and then overdubbed a lap steel part on the guitar bought for him by his aunty upon his departure for New Caledonia in the mid-1960s. These takes were recorded through multiple amplifiers using close and room microphones to create eight tracks of audio to accompany the film. During the mix, extensive use was made of automation so that each layer of audio could respond to the pictures both in terms of the film’s narrative, and with respect to the textures, colours, and other subtle visual elements present in the film.

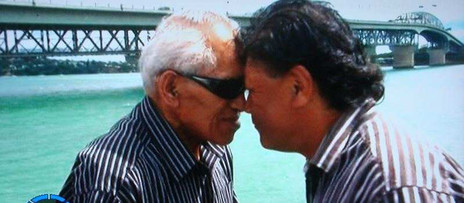

Ben Tawhiti died on 15 September 2012, aged 78. After a visit to Otawhiwhi marae in Bowentown, his body was laid to rest on Rangiwaea Island. A memorial concert was held at the Hopetoun Alpha, Auckland, featuring John Rowles, Dennis Marsh, and a seven-piece showband. Tributes flowed online from the many musicians whose lives he had touched.

In his 1995 interview with Suzanne Ormsby, Ben reflected on contemporary Māori popular music: “A lot of the songs composed by young Māori today are political and the fact is that Māori music is telling about the wrongs that were done. Our young people are starting to get on board regarding that era now and they are voicing their protest through some kind of movement or through music.

“I think music is one of the greatest medicines on earth.”

“What can we say about people who want to write about their oppression and how they feel about it? If they want to protest through song, that’s a good way to do it. We just keep at it and it may be slow to some people, but we are starting to have some of the wrongs righted. You know the government is looking at it thankfully and I hope it continues for the sake of our grandchildren. At the same time I say to my people, ‘Hey don’t sit on our backsides. Get up and do something! Do something about it so that when that day comes we will be prepared.’

“Music brings people together. You hear someone playing the guitar and you all go and sit around. I think music is one of the greatest medicines on earth. I love it.”

--

Thanks to Suzanne Ormsby, whose interview with Ben Tawhiti and many other musicians appears in her 1996 University of Auckland MA thesis Te Reo Puoro Maori Mai I Mua Tae Noa Mai Ki Inaianei, The Voices of Maori Music, Past Present and Future: Maori Musicians of the 1960s. Thanks also to Michael Colonna.