AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

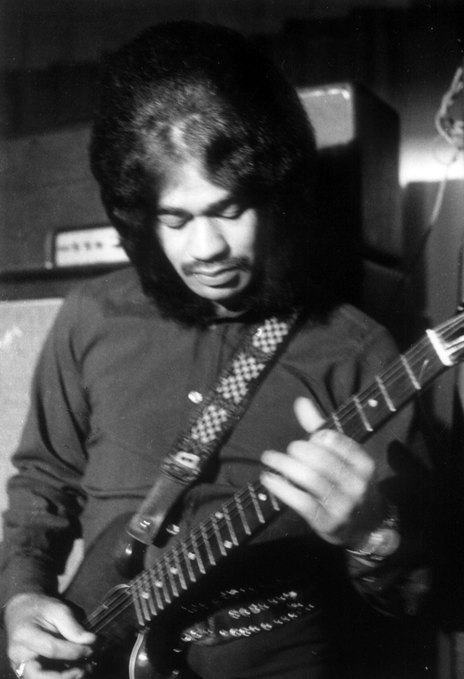

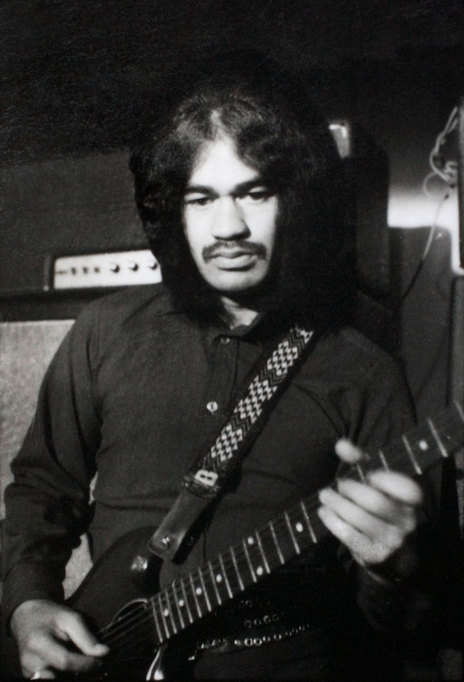

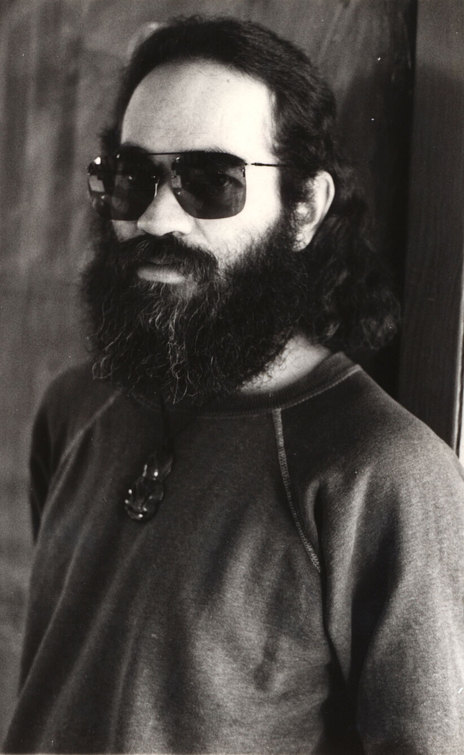

Billy TK

aka Billy Te Kahika

What is certain is that Jimi Hendrix was an icon and model for many young Māori men. In the late 60s and early 70s they could be found up and down the country, playing guitar in the style of the great innovator, often sporting a Hendrix-like afro and flamboyant apparel to match.

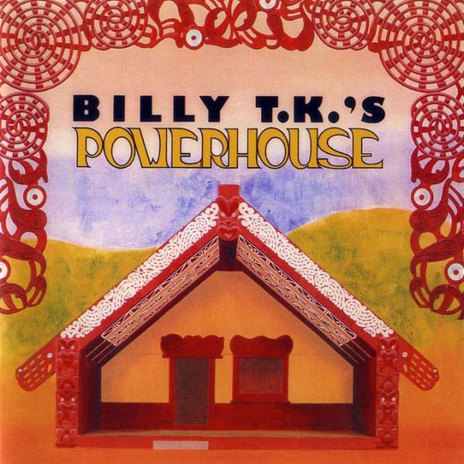

No local musician embodied this archetype more – or took it further – than Billy TK. His recordings with The Human Instinct, in particular the album Stoned Guitar, remain emblems of the period, and are today both historically significant and highly collectible. His subsequent work with groups such as Powerhouse and Wharemana have built on the style and technique he developed during this time.

Billy TK’s story began in Bunnythorpe, a rural township just outside Palmerston North. Born Billy Te Kahika, his surname was abbreviated by his Pākehā schoolteachers, who couldn’t be bothered writing out his full Māori name.

His parents were custodians of the local camp, where construction workers on the hydro-electric towers being built all over the lower and central North Island made their temporary homes. “The workers would party at the weekend,” he remembers. “And I’d hear all these guitars and singing at night. That was how I was first introduced to all the party songs, the island songs, the Māori songs. I thought, ‘Gee that’s great. I want to learn to play guitar too.’ My cousin who was staying with us knew how to play three chords. I remember putting my hands on the fretboard.”

As a beginner guitarist he sometimes got to sit in amongst the trumpets and saxophones, learning the waltzes and foxtrots popular with his parents’ generation.

And there were dance bands at the Bunnythorpe Hall. As a beginner guitarist he sometimes got to sit in amongst the trumpets and saxophones, learning the waltzes and foxtrots popular with his parents’ generation.

Rock and Roll

But he was more excited by the newer sounds he was hearing on the radio: Elvis Presley, Bill Haley, Little Richard, The Everly Brothers; the sounds of rock and roll. “That would have been in the 50s, coming on into the 60s. I started to learn all those songs, ‘Bye Bye Love’ and so on. They were good guitar players, The Everly Brothers.”

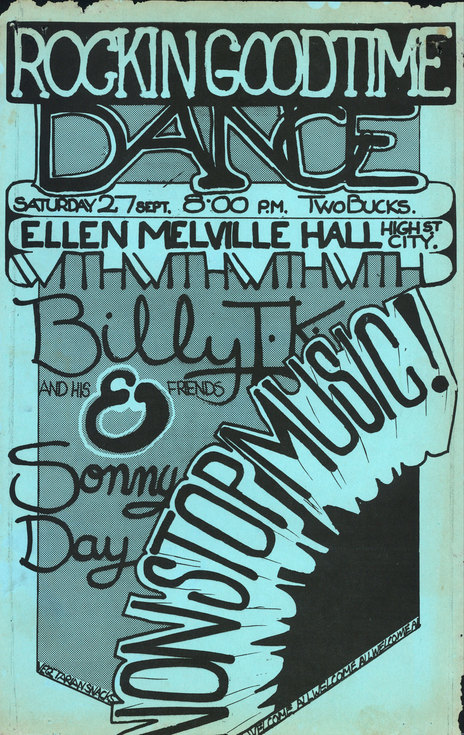

Before long he was taking his guitar into Palmerston North for weekend sessions in the Orange Hall, where veteran musician, Ben Ngatai, ran the youth club. His son, Ben Ngatai Jr, was Billy’s contemporary and already an accomplished player. He was the guitarist in the youth club band, which Billy quickly joined. Naming themselves The Premieres, they modelled themselves on The Shadows, emulating Hank Marvin’s clean guitar style. Billy travelled with The Premieres to other youth clubs in Wanganui and Lower Hutt. He also began spending time in the fertile musical environment of the Rātana settlement near Wanganui, heart of the religious and political movement founded by the Māori prophet Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana.

The advent of The Beatles was another turning point and by 1964 the Premieres had evolved into The Sinners. With a line-up of Billy, Ben Ngatai, Ted Cash on drums, Sonny Ratana on bass, Harold Hine on rhythm guitar and lead vocalist Theo Swanson, they satisfied audience demands for the popular Merseybeat sound, seasoning their sets with the bluesier material they preferred – songs by The Pretty Things, The Animals, The Spencer Davis Group and The Yardbirds.

Fuzz and distortion

It was through studying the records of such groups that Billy became curious about distorted guitar sounds. “The Pretty Things and Yardbirds were using fuzz and distortion and I didn’t know how they were getting it. I kept on listening and listening. Then one day a friend of mine from the Rātana pā, Ara Mete, had a distortion pedal. ‘Here, try it!’ All this noise came out and I said, ‘Yes! That’s me.’ So I took it to an electrician downtown and he copied it and made me one. I’d sit with him as he soldered and unsoldered things until we got it. I started practising with it and getting better.”

“I heard Hendrix and realised he had taken it another step."

– Billy TK

Then came Hendrix. “We were just a little bit along the track with our distortion and experimentation [when] I heard Hendrix and realised he had taken it another step. The first song I heard him play was ‘Stone Free’, on the back of the ‘Hey Joe’ single. The solo was just phenomenal. So I ran out and grabbed the album to learn everything I could. We were the first people in our area who could play the album, top to bottom. I’d learn the bass parts first, then Sonny and I would work out how the guitar parts went.”

By this time Billy was also hanging out with another local guitar hero, Reno Tehei. As a member of Wellington band Sounds Unlimited, Tehei had already travelled to the UK where he had seen Hendrix in person – a mind-altering experience. Back in Wellington he had formed a Hendrix-style trio, The Joyful Crye, in which he recreated Hendrix’s full box of tricks, including playing the guitar with his teeth while rolling on the floor, and through a wah-wah pedal, which he had brought back from Britain. (Rumour has it he stole the pedal from a band onstage while they weren’t looking.)

By the end of 1967, Tehei had taken his trio to Melbourne where he renamed them Compulsion. With the Sinners in disarray, Billy headed for Melbourne to hang out with Tehei. The pair continued to trade Hendrix licks offstage, though Billy didn’t find any regular work as a musician.

The Human Instinct

Then came a call from New Zealand. It was Maurice Greer, a young drummer from Palmerston North with global ambitions. Greer had gone to the UK as the singing/standing/drumming frontman for a beat combo called The Four-Fours. Now they were back – newly psychedelicised, renamed The Human Instinct and looking for a guitarist.

Billy remembered Maurice; they had attended the same high school in Palmerston North, Queen Elizabeth Tech, though had never played or even talked music together. Maurice was the youngest of three brothers, all involved in the music business; his brother Frank had run a Palmerston North nightclub.

With the lure of regular work, Billy returned to New Zealand, where he joined Greer and with a revolving door of bass players (Michael Brown, Peter Barton, Larry Waide all passed through) began touring the country in a Mark II Zephyr, dragging their equipment in a trailer.

Greer still had his sights on the British market and the Human Instinct returned there, this time with Billy, in early 1969. Greer was hoping to build on the contacts he had made there on his earlier visit, when the group had released two singles for the British label Deram.

“We arrived in mid-winter and it was so cold,” recalls Billy. “We were hoping to meet up with Maurice’s friend, Clive Coulson, but he had joined Led Zeppelin as a roadie. We tried to get under the same management as Zeppelin, but they were in America and Maurice couldn’t get hold of them.”

They brought with them a full Marshall PA and backline, ensuring they would be the loudest thing anyone here had ever heard.

Though they failed to secure much in the way of gigs, recording or management interest, they did acquire a mighty stack of equipment, and when after three months they sailed back to New Zealand – with the promise of a residency at Auckland’s Bo Peep Club - they brought with them a full Marshall PA and backline, ensuring they would be the loudest thing anyone here had ever heard.

That year they recorded their first album, Burning Up Years, at Auckland’s Stebbing Studios; the first documented evidence of Billy’s increasingly thrilling guitar playing. Billy fondly recalls the studio’s 4-track recording gear, and the surprisingly professional results the studio’s founder Eldred Stebbing could achieve with it.

“He kept on running up and down these steps, he was always changing something, and his wife Margaret would turn up with a cup of tea and pikelets. Eldred was such a switched-on guy, and this was the sort of music that he liked anyway, groups like us and The Underdogs.”

For a rearrangement of The Kinks’ classic ‘You Really Got Me’ (featured on Burning Up Years and – in a different version – on a single) Billy experimented with overdubbing his solo, then playing it backwards against the track, achieving the same psychedelic effect pioneered by Hendrix and the Beatles

Meanwhile The Bo Peep was becoming known as a haunt for fellow musicians. “Everyone used to come down to The Bo Peep after hours, all the musos. We’d play till dawn. Fridays and Saturdays it was daylight when we finished. And queues to get in used to run right around the street.”

Stoned Guitar

The Instinct’s second album, Stoned Guitar, captured the ambience of the Bo Peep, with the powerful triumvirate of Greer, Waide and Billy’s extended soloing.

“I was playing a Gibson SG at that stage and that fed back fantastically. It could hold the frequencies of the feedback. And I had a custom-made wah pedal and custom made distortion pedals and a Wem tape echo unit.”

Recorded mostly at Mascot Studio, Stoned Guitar proved a challenge for the engineers who had never encountered anything like Billy’s volume or approach to sound.

The title track, the sole Te Kahika original, was a showcase for his guitar pyrotechnics.

“I wanted to do a piece that reflected the feedback, the state we were at [with it] at that time. It was never planned. I started off playing with the echo unit and built it up with the distortion pedal and the wah and then went into the riffs. It happened, bang. No rehearsal.”

Like Burning Up Years, Stoned Guitar featured two songs credited to Jesse Harper. This was a pseudonym for Doug Jerebine, one of the most respected guitarists on the Auckland scene. Jerebine started out with showbands such as the Mike Perjanik Group and the Embers, and moved into studio work with the likes of The Chicks and Dinah Lee. Like Te Kahika, Jerebine had been profoundly affected by Hendrix and the songs he had composed as Jesse Harper showed a strong Hendrix influence – they were originally recorded in London in 1969 as demos for a possible solo record deal. When this failed to eventuate, Jerebine took further work as a sideman before travelling to India where he stayed for more than a decade.

Never one to miss an opportunity, Maurice Greer asked Jerebine if the Instinct could use his unreleased material. Jerebine gave the Instinct his blessing (though he was reluctant to teach Billy the guitar parts) and songs like ‘Blues News’, ‘Ashes and Matches’, ‘Midnight Sun’ and ‘Jugg-A-Jugg Song’ were among the strongest material on the first two Human Instinct albums.

Stoned Guitar was released in 1970. Its relatively high sales in New Zealand may have been helped by its budget price.

The Human Instinct recorded Pins In It, their third album (and final with Billy) in 1971. Making more use of overdubbing and with a greater number of original songs, it was the Instinct’s most sophisticated set so far. Waide had been replaced by Neil Edwards of The Underdogs, who contributed to the songwriting, as did his mother. Billy weighed in with two originals, ‘Highway’ and ‘Playing My Guitar’.

With Pins In It released, the trio headed to Australia. “We had our Marshall gear with us and we got an apartment in Sydney and set about hooking up with an agent and getting work. We were getting a bit of TV and starting to build, and then we were at this club one night and in one of the songs Maurice started swearing – just for fun – but management took it the wrong way. It got sticky and I just thought, maybe it’s time to do my own thing.”

Powerhouse

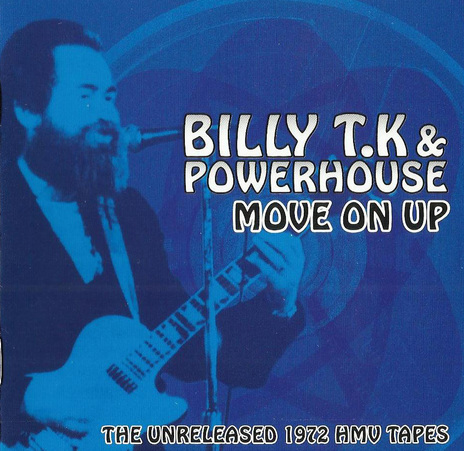

Billy returned to New Zealand in October 1971 with Australian drummer Steve Weir and formed the first line-up of Powerhouse, which for the next eight years would see a series of continually changing line-ups.

Initially, a quartet (with Gavin Collinge on bass and John Bilderbeck on guitar), Billy TK’s Powerhouse secured a residency at Wellington club Lucifer’s where they played a mixture of rock and soul covers, ranging from Neil Young to Curtis Mayfield. Later that year an opportunity arose for Billy to start his own club in Palmerston North, so he returned to the Horowhenua, where Powerhouse took up residence at the newly opened, Boulevarde club.

This version of the band was recorded in Wellington’s HMV studios for a possible album, however, nothing was released at the time. These recordings finally emerged in 2009 as Move On Up: The Unreleased HMV Tapes, and show a club band in its embryonic stages, albeit with an unusually fiery guitarist.

Billy began adding musicians to the line-up, expanding the tonal and rhythmic possibilities.

Playing regularly at the Boulevarde, Powerhouse began to grow in scale and ambition. Inspired by the current jazz-rock fusion of Santana and John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, Billy began adding musicians to the line-up, expanding the tonal and rhythmic possibilities. These included keyboardist Jamie Tait-Jamieson, percussionist Mana Rauhina, cellist Pauline Poole (who later become a well-known singer under the name Hattie St. John) and singer Mahia Blackmore. Following the departure of Steve Weir, the group went through a number of drummers including Bud Hooper and Neil Storey, who would go on to play with Dragon before his untimely death. At the time he joined Powerhouse he was still at school.

“I was auditioning drummers, I’d tried a couple and there was this kid out the back in a school uniform and I said, ‘Have you come to audition?’ He said, ‘Yeah’, so I said, ‘Hop on’, and he was it. He had it. So I had to go and talk to his mum!”

Sometimes Billy’s old friend Ara Mete played drums; on other occasions, he would play second guitar.

In the communal spirit of the time, the group took up residence in a rural mansion in nearby Cheltenham, made available by a friend of the band. Each member had his or her own room, there was space to rehearse and even tennis courts. It also provided inspiration for Billy’s original writing, which increasingly dominated the repertoire. Band membership at the time swelled to as many as 15 people.

“We weren’t worried about money. Money wasn’t the issue. It was for the art, if you like. We just used to all try to help each other, like one big family. That held us together.”

Festival fare

The first month of 1973 saw the first major New Zealand music festival, held at Ngaruawahia. Billy TK and Powerhouse played, taking the stage directly after headliners Black Sabbath. Other festivals followed: Nambassa, Sweetwaters, Brown Trout. Powerhouse, with their expansive line-up, were ideal festival fare. They also became regulars on the burgeoning university touring circuit, established by Wellington promoter Graeme Nesbitt. Between 1973 and 1975, Nesbitt paired Powerhouse with groups such Mammal, Butler and BLERTA for numerous campus concerts around the country.

The Powerhouse of this period is best represented by the 1990 release Life Beyond The Material Sky, issued as a double-LP by the German label Little Wing. Recorded at Wellington’s St. James Theatre in 1975, it captures the big ensemble in full fusion effect on a largely instrumental set of Te Kahika originals.

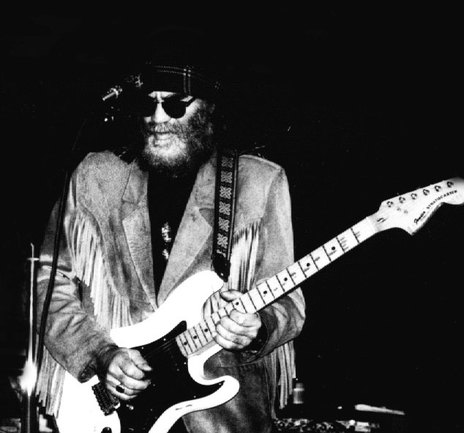

But by 1977 Billy was becoming restless. “There were other things that I was starting to get into. I started to dig deeper into my spiritual side, and that started to come out in the Powerhouse’s music, and from that, I started looking at which direction do I want to take now?”

Hollywood

Powerhouse played their final gig at the appropriately named Sunset Festival in Mount Maunganui in 1977. Soon after, Billy left for the United States. Keen to learn more of the industry, he based himself in Hollywood for over a year. A management and production contract gave him the use of a studio and freedom to experiment, though he did not own the copyright on any of the recordings. During this time he played with members of Quincy Jones, Chick Corea and Stevie Wonder’s bands. Some of these players can be heard on ‘Dance With The Spirit’, a funky single recorded in the USA and released in New Zealand in 1980 by EMI.

“They would say to me, ‘what about your indigenous stuff, do you ever do any of that? We’d love to hear that!’ And that sort of stuck in my mind.”

– Billy TK

While he could hold his own in these jazz-funk fusion settings, the American musicians were more curious about Billy’s Māori roots than hearing him play blistering lead breaks. “They would say to me, ‘what about your indigenous stuff, do you ever do any of that? We’d love to hear that!’ And that sort of stuck in my mind.”

In 1980 he returned to New Zealand with the idea of creating a contemporary group incorporating indigenous sounds. Calling his new band Wharemana – a Māori translation of Powerhouse – he did just that. The large ensemble included traditional dancers, vocals in Maori and electrified the six/eight rhythm of the haka. At one point, Wharemana toured New Zealand with UB40.

Though for a while Wharemana was supported by a government arts funding scheme, it ultimately became too costly to maintain, and since the 90s Billy has scaled back, sometimes touring with just a drummer, playing a mixture of crowd-pleasing favourites from the Instinct era, Powerhouse fusion workouts and newer originals.

Legacy

He continues to be held in high regard as a musician. When Carlos Santana played in Auckland in April 1996 he invited Billy onstage as a guest and turned over the spotlight to him for a version of ‘Black Magic Woman’, one of Santana’s signature songs. By this time, psych-rock collectors around the world were paying hundreds of dollars for original copies of The Human Instinct’s albums.

Billy has also played cameos with younger New Zealand musicians. He played on The True School, the breakthrough album of hip-hop producer DLT has guested with alternative rock group King Loser and performed with Māori singer-songwriter Emma Paki.

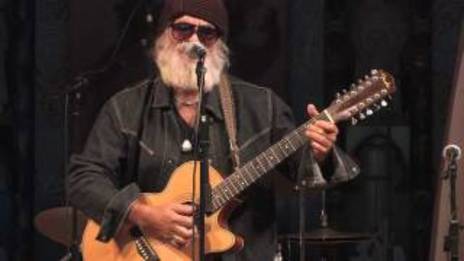

His sons Billy TK Jr and Mara TK have both made careers in music, Billy Jr as a frenetic blues exponent, Mara with the electronic funk group Electric Wire Hustle. Billy has performed with both sons. At the 2013 Womad festival in Taranaki, he appeared with an expanded Electric Wire Hustle line-up – the Electric Wire Hustle Family – and also guested in a set by Dunedin guitar hero David Kilgour, who told the crowd he had been waiting for the opportunity to play with Billy for a very long time. Billy, with long grey beard, hat and dark glasses, looked more like a member of ZZ Top than a Māori Hendrix, but he sounded like no one else and played with as much fire as ever.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air