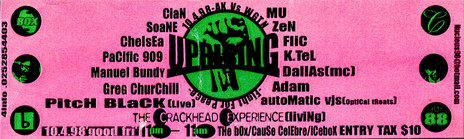

Benny composed and performed the music for the opening ceremony dance performance at the 1990 Commonwealth Games, featuring 6000 dancers. he founded The Crackhead Experience, the three-piece beats-and-bleeps collective with Dallas Tamaira and Chris “Mu” Faiumu that would help inspire and inform the formation of Fat Freddy’s Drop.

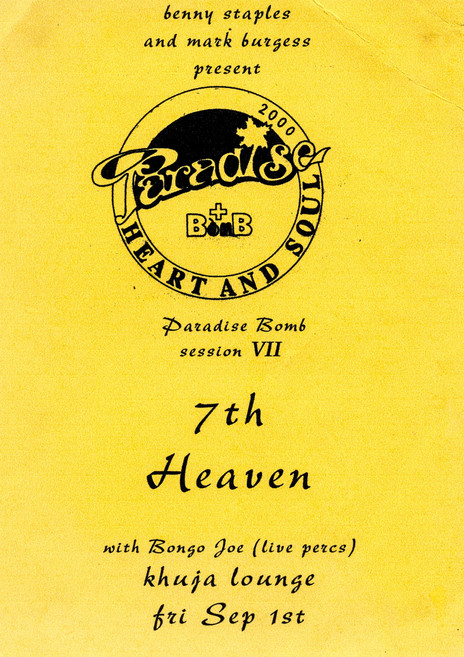

In 2004 Benny wrote and produced a solo album under the moniker T-Son, or, The Sound of Newton. He is also an eclectic and informed DJ, and was one of the first people to bring Auckland and Wellington club talent together for the landmark Easter 1998 Uprising at The Box and Cause Celebre.

Benny is a fiercely loving father to daughter Billie, son Sol, and wife Anna Palmer, as well as a passionate philosopher and raconteur. These are aspects of his personality and outlook that inform his approach to music. For the nearly five hours I sat with Benny behind his Matakana-based house and studio – excitedly watching and listening to him duck and weave through stories, records, and ideas – there’s a sparkle in his eyes. He’s at once child-like in all the best possible ways, yet at the same time intensely informed and focused. What I already knew becomes even more apparent. His passion and commitment to (and more than considerable talent for) music is undeniable. His output is perhaps less recognised in New Zealand than it should be.

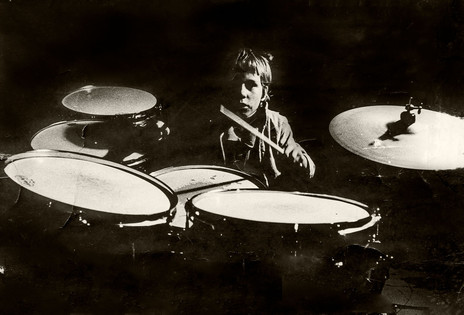

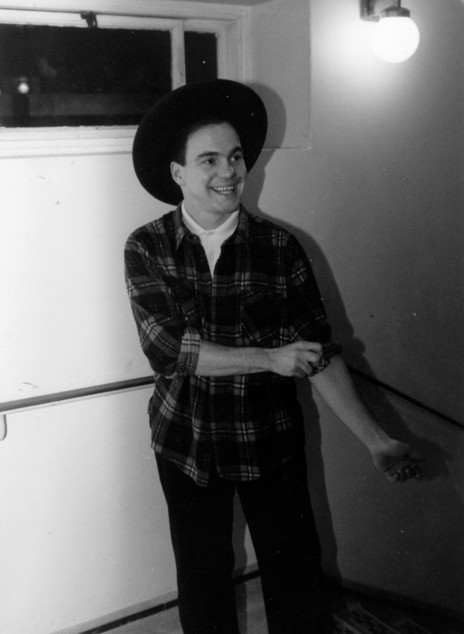

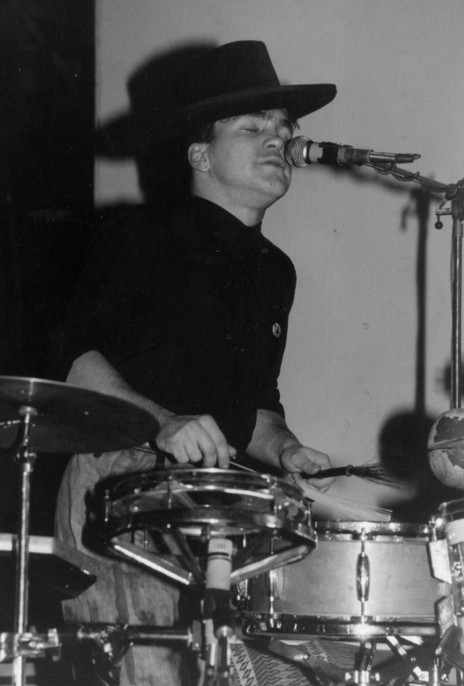

At some point I question him about how he became a proficient drummer at such a young age, and how he developed such a bloody-minded focus on art and creativity.

“I was incredibly lucky … because from zero to 10 my mother and father pumped me full of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Dylan, Stones, The Who, Lou Reed, Bowie, and blues and jazz. By the time I was 12 they were some of my heroes. My Form Two talk to the class was on the history of music, a little bit of classical, blues, jazz, folk, Dylan, pop, and Beatles. I finished with rock and Lou Reed’s ‘Sweet Jane’. My teacher Mr Kane had been in a glam band before teaching and he sat smiling at the back of the class. Mr Kane was so cool … he used to bring his Les Paul guitar in and the whole class would sing! Wonderful. You never forget those teachers!

“At home we never had a TV, but we had books and records, and we had the books that were banned at the time.”

“At home we never had a TV, but we had books and records, and we had the books that were banned at the time, like Miller and Selby Jr. Both my parents loved music and listened to it all the time, but they had no musical talent. I tried guitar but my fingers were too small. Then I was really interested in the violin, but it didn't work out due to unhappy teachers, and so I eventually got to the drums and built a kit out of junk with one piece of real of hardware, a Ludwig speed king bass drum pedal. I started to practise and taught myself. All my favourite musicians are self-taught, James Brown being the obvious example, Prince as well. Prince couldn’t even read music.”

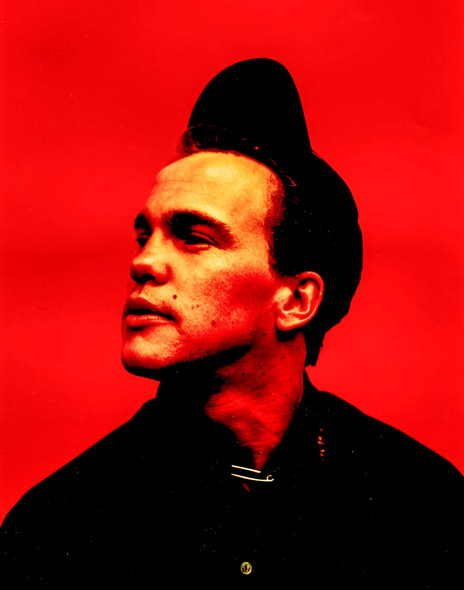

A young Benny’s reaction to traditional methods of teaching makes sense, seeing as he would later identify more meaningfully as a punk. In the interim, the school system often presented itself as problematic.

“I had to separate home and school. I wasn’t interested in what they were trying to teach me at school. It wasn’t real. It was a vision of New Zealand as a Victorian wasteland. You had to be upper class to get a chance to read poetry and Shakespeare and things like that. Everything I learned at school was a lie. Like there’s no racism or class system in New Zealand. I was a punk, I got it grief all the time. I’d go out – I was 15, had started cutting my own hair, I’d maybe have my father’s jacket on – and someone would yell, ‘hey you f**king punk shit!’ I just looked different to everyone else.”

He continues, “I had a teacher pull me up once in front of everyone and say ‘you’ll never get School C’. But I’d not done anything. I just don’t get that, still don’t. Maybe if I’d done something to the guy. I was just minding my own business … I was probably thinking ‘what does God save the Queen mean?’ Or something, in my own thoughts [laughs]. Anyway, I got School C. I got UE.”

Pondering the finer points of what ‘God Save The Queen’ meant was not born of a particular affinity with Her Royal Highness. Rather, Benny had seen and heard the words of John Lydon, broadcast during the desperately sparse days of New Zealand television.

“When Dylan Taite filmed a thing on the Sex Pistols, it was on at 11pm and I was 14, and John Lydon looked into the camera. I’m sure thousands of young New Zealanders went ‘that’s me, he’s articulating what I feel, and he’s been treated the way I have been treated, and he’s stepped outside the pre-determined role.’”

He continues, “I realised right away that’s who I was. Even when I was 11 people would say ‘you’re too into music’. It was difficult to find my place. Making me feel like having a passion was a sin. To me having passion is a good thing. Lydon is up there with Miles and Prince as far as I’m concerned, a true artist. Someone who does what they want, and for good reasons. Integrity, authenticity, all these things most pop stars don’t have. Luckily I got to thank Dylan [Taite] for that interview many years later.”

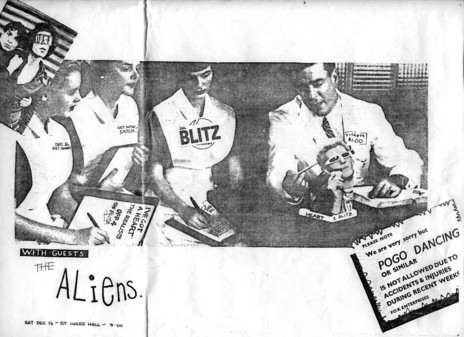

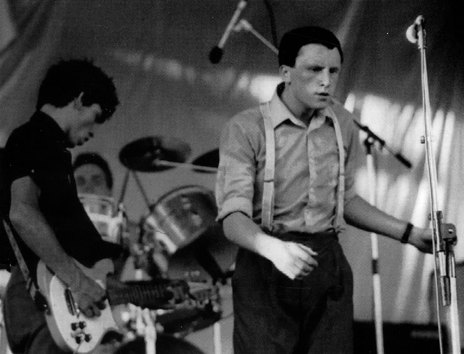

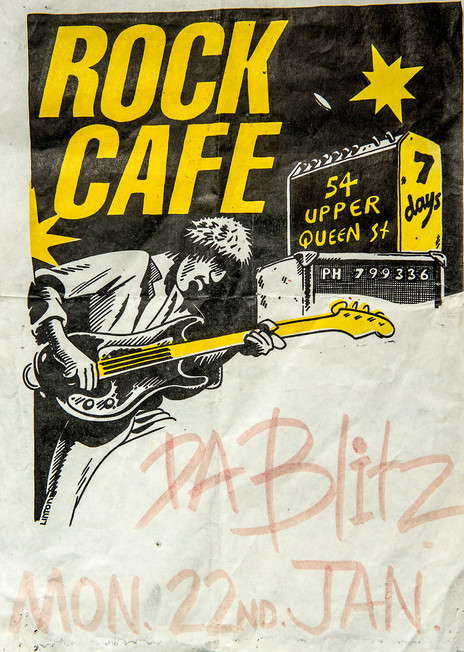

Despite the seemingly draconian influence of the New Zealand school system, Benny was energised by music, as well as the sage teachings of Johnny Rotten. “I got my first real drum kit at 14 and joined the 4E Blues Band. The classes were streamed, so E wasn’t ideal. I eventually convinced those guys that we should be a punk band, but they had uninformed ideas about what punk meant. But we got there, and renamed as Da Blitz [laughs].”

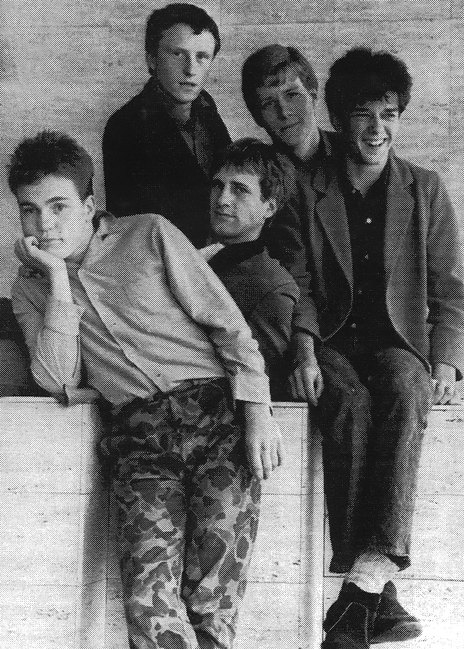

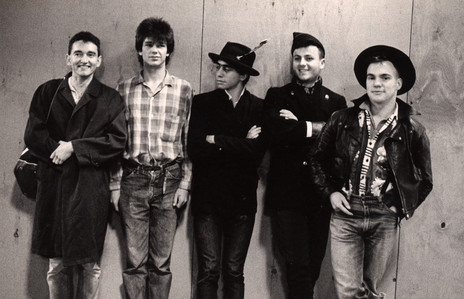

Upon leaving school, Benny was quickly recruited by The Newmatics.

Around this time Benny realised he also had an inclination toward the blacker end of the music spectrum. “In 1977 I was 14. I walked past a club called ‘Babes’ and I heard a track which later on I found out was ‘Flashlight’. I remember loving that. I’d never heard anything like that before. I stopped and listened. I’d never heard a bassline like that before. Played on a Moog by Bernie Worrell. Many years later we hired him for a Woodentops session in New York … a truly incredible player.”

Upon leaving school, Benny was quickly recruited by The Newmatics, a post-punk band elevated by his drumming style, and one of the bands that would tour during the divisive days of the 1981 Springbok Tour. “They were older, three or four years older than me. They found me through an older woman I was in a relationship with; a woman I’d met at a theatre group who was twice my age. I was exposed to a lot of adult concepts … street theatre was very cutting edge then, very political. So anyway Syd [Pasley] rang me up and we had a chat about The Clash, and we agreed about their movement into black music, how exciting that was, and about bringing other sounds into the punk sound in general.

“The band lasted less than two years, but things were so exciting and so intense. Gigs man. You didn’t know whether it was going to end in a riot or a love fest or what. We did that double EP, Broadcast O.R., with that pic with the cops smiling with their batons inside. That photo was from the Auckland Star. That would never be published now. Kind of embarrassing for the cops. We knew first-hand about the police’s preparation for the [1981 Springbok rugby] tour too. Nine months before it started the police riot squad had come and practised with their new gear on our audiences. Those in power knew what was going to happen and they could have stopped it. They could have stopped the tour.

“The band tour that coincided with the apartheid protests was called The Screaming Blam-matic Roadshow. It was an incredible line-up with The Screaming Meemees, Blam Blam Blam and The Newmatics. We did a triple header with the bands alternating each night and a combined romp at the end … ‘Land Of 1000 Dances, ‘I’m A Believer’, ‘These Boots Are Made For Walking’, ‘My Girl’s Got Pointy Ears’ … it was wild. When Mandela finally got released he thanked New Zealand for the anti-tour movement’s support. It was a brief moment in New Zealand where there was real progressiveness. Bastion Point, the anti-tour movement, women’s liberation beforehand, the anti-nuke movement. I’d say 79 to 84 was really progressive.”

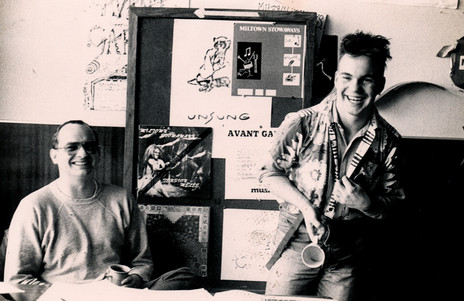

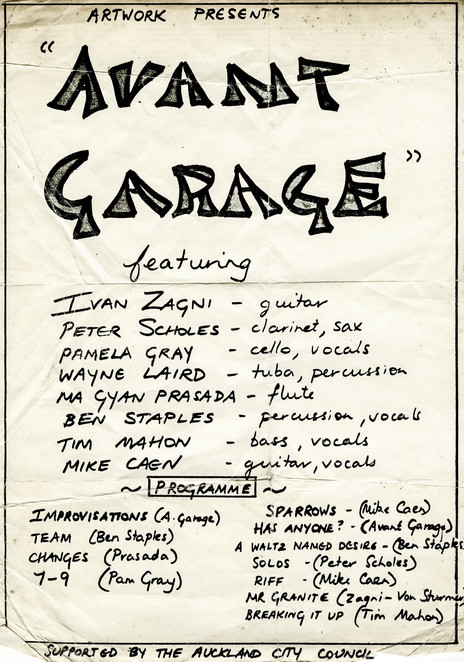

Following The Newmatics disbanding, Benny played briefly with The Prime Movers, before collaborating on two projects he cites as being of immense significance; Avant Garage and The Miltown Stowaways.

“The Miltown Stowaways were a leftist collective, bringing funk, jazz, and punk elements together. At the same time I was involved with them, I was also part of a group called Avant Garage, one of the most important projects I’ve ever been involved in. We were paid wages by the Auckland City Council to go and play at schools and so on, which was essentially a scheme to get musicians on the dole working. The project was coordinated by Ivan Zagni. He’d just moved to New Zealand and had once been invited to join [Frank] Zappa, which at the time was like getting a call from Miles [Davis]. I wasn’t allowed to have a bass drum in Avant Garage. Ivan said no bass drum and I said ‘yes boss’. That was good because I wanted to stand up because I’ve always been a dancer. I’ve always loved dancing. I’m just as much a fan and a dancer as I am a musician. I think it’s really important to hold all of that together. If you start getting cynical then the music suffers.

“We did everything for that project. Artwork, distribution, everything. Then Ivan brought the whole idea of free music. Free jazz. Combining classical and punk. He showed us something I had an innate feeling about already, that anything was possible with music. Just meeting someone like that, who’d played around the place and reinforced what I was feeling. I’d never met someone like him. He gave me confidence too. Confidence in my songwriting. Because when you’re a drummer there’s all this prejudice, the jokes and so on. But anyone in a band knows you are only as good as your drummer.”

At this point Benny makes a couple of many afternoon trips to the turntable, and I am treated to The Miltown Stowaways and Avant Garage, two bands who up until eight minutes ago I had no idea had ever existed. I feel concerned, though I don’t let it show. Both bands are good. Really good. But I can’t help but think about how much great art simply disappears over time, or perhaps even never makes the impact it should the first time around. My thoughts are broken by Benny’s excited commentary. “It’s punk funk, and I’m yelling Jah, but in a very aggressive way … not a ‘jah mun’ kind of way, but ‘JAH!’” He pauses for thought. “All good music is the same. It’s about tension and release. Fela Kuti is probably the best example of that, bringing it back up with the horns.”

Benny’s observations about Kuti are not dissimilar to many of his contemplations over the afternoon. Extraordinarily well-read, listened, and informed, his reflections on his career are often punctuated by contextualising his experiences and beliefs as an artist within the canons of popular music history. At some point I suggest genre labels can be restrictive, to which he replies, “I really like what Duke Ellington said. There’s two types of music, good and bad.”

He also feels strongly about the role art and creativity can play in wider society, with a love of Aotearoa and New Zealand conflicted by his observations of how the nation often functions. “I really hate it when politicians say ‘oh that was the pragmatic thing to do’ because often the pragmatic thing to do is not the best thing to do, and we’ve lost all distinction it seems. And it’s not a very poetic word … and we need more poetry. That’s what I used to ask on my George FM show, ‘where are all the poets?’”

Energised with the punk spirit as well as a love for black music, Benny travelled to New York, before moving to London in 1984, where he settled in a squat. At a friendly dealer’s place he met Nick Kent, legendary NME writer and musician, soon after joining Nick’s band The Subterraneans. “I freaked out meeting him the first time. It was like ‘oh shit, this is possible’. By moving to London and getting involved I could meet these people, I was in the right place. So I started jamming with others and looking for the right group for me.

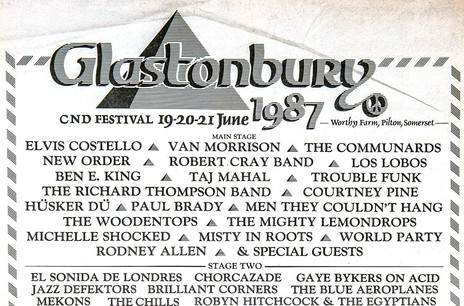

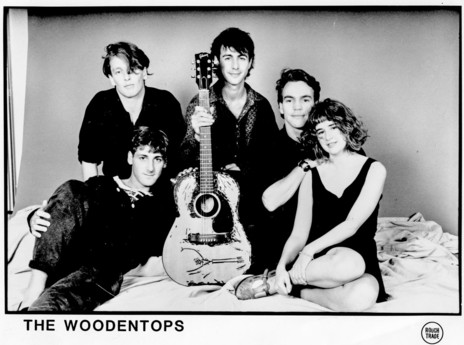

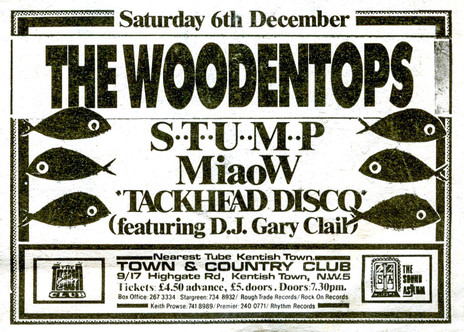

“So the bass player in a band I was helping out in was talking about his friend Paul who was drumming for The Woodentops, and said he was leaving. Then at the same time Kelly [Rogers] who was with me in The Newmatics was in London as well, and he’d put an ad in the Melody Maker looking to start a saxophone quartet. He got a call from Geoff Blythe [Dexy’s Midnight Runners]. And he goes ‘Benny, Geoff Blythe rang up!’ And I go ‘Geoff Blythe Dexies?’ And he goes ‘yes Geoff Blythe Dexies!’ So he got a call from one of our heroes, and then I met him. At the same time, without me knowing, Geoff had seen me playing in the band I was subbing in, and had told Rolo [McGinty, The Woodentops’ founder], ‘I’ve just seen your new drummer’. Meanwhile, there was a Kiwi lad working at the NME at the time, David Swift from Christchurch. So I rang him up and said ‘David! Have you got any contacts? I hear their drummer is leaving.’ So he had the contact for their press officer, and I was so bold back then, no fear. I had no idea I already had this connection opening up through Geoff Blythe. So I ring the press officer, but he’s got no idea what is going on. He has no idea the drummer is leaving! The band hadn’t told anyone outside the inner circle! But after the initial shock we did have a chat and he did pass on my number [laughs]. Sure enough I got a call.”

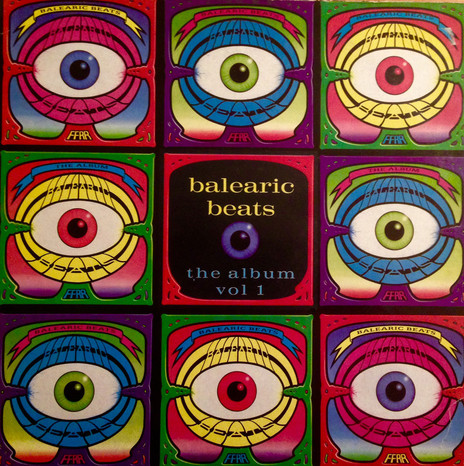

The Woodentops recorded ‘Why’, a tune that would become an early Ibiza club hit.

The Woodentops recorded ‘Why’, a tune that would become an early Ibiza club hit, in turn inspiring the likes of British DJs Danny Rampling, Paul Oakenfold, and Nicky Holloway to propagate what became known as the Balearic sound and subculture into the evolving UK rave scene. ‘Why’ was taken from Live Hypnobeat Live (1987), the album that was recorded at the Palace Theatre in Los Angeles, sandwiched between their two studio albums. Still remixed today, ‘Why’, or the chorus at least, is familiar to generations of dancefloors. “It never died. It’s part of the Balearic culture. We recorded that the first time we’d tried ecstasy, and then it took off in that scene, a scene I’d not yet discovered.”

Benny further explains the provenance of the track, as well as the significance of DJ Alfredo. “The track ended up in the hands of Alfredo, widely credited as the pioneer of Ibiza’s Balearic sound. He had fled the Argentinian dictatorship in the 1970s, settling in Ibiza and establishing a sound all of his own in his DJ sets. If he hadn’t played ‘Why’, and those British DJs hadn’t heard it on their first E, history would have been different. Anytime he talks about the Balearic thing Andy Weatherall still talks about The Woodentops – and I love a quote I read from Shaun Ryder where he said ‘I don’t like indie music. I like Woodentops 12 inches though!’”

The Woodentops recorded with producer Adrian Sherwood, renowned for his distinctive and pioneering Jamaican-influenced dub mixing techniques. Benny credits Sherwood with informing his own production style, as well as tangentially allowing him to work with Lee “Scratch” Perry.

“We were back at The Roundhouse and I went into the lounge and I took one look at this little guy who looked like an old tree. And I thought ‘fuck, that’s Lee Perry!’ So I went running back into the control room and I was like ‘Rollo, Rollo! Lee Perry’s in the fucking lounge bro!’ So we both crept back out, and I whispered ‘we have got to invite him in’. So we go up to him, but then I’m like, ‘What the f**k do you call him?’ Then I remembered that if you become involved with James Brown you have to call him Mr Brown, so I thought ‘well I’ll start with Mr Perry’. I mean, what do you call him? I’ve never met him before. Lee? Your Highness? Your Purpleness? [laughs] Your Madness Sir?? I mean, doth your cap, you’re in the presence of genius here. This guy had helped The Wailers so much. So we went up to him and said ‘excuse me Mr Perry, nice to see you at the studio … um … we’ve been working with Adrian Sherwood, so we’ve heard a lot about you.’

“Then Perry said ‘Oh munnn, I’m at the wrong studio, I’m meant to be at the Townhouse!’ We’re at the Roundhouse in North London, he’s meant to be at the Townhouse in West London! So he was in the wrong place, but we said ‘come in’. We wanted to play him what we were working on. That was wicked. I was in heaven. One of my dreams had come true. I was actually so ambitious that I wrote a list of people I wanted to see perform when I got to London, and this was better. First he went around all the equipment. We’d just bought this computer and he was like ‘nah … computer crap’, and he did voodoo on it, then went into a riff about the music business destroying everyone, ‘it destroy Bob, it destroy The Clash, it destroy me, but I still alive’. He spoke in riddles, but riddles that made complete sense. That’s how I like my geniuses, they’re eccentric, they’re not straight. You can’t achieve great work thinking straight. It comes out mediocre.”

Perry would go on to name The Woodentops’ second studio album that day. “He asked what we are working on, then we give him a glass of wine and a bit of Afghani Black. So there I am having a spliff with Lee, and he was brilliant, and we played him a track and it was a slow one, ‘Wheels Turning’, and he goes ‘OK I’ll go and record now’. And we were like ‘fucking hell, we haven’t even asked him!’ And off he went and did a brilliant vocal that we couldn’t include because of record company stuff, but we gave him a credit for spiritual guidance on the album because he made that day for us. ‘Wheels Turning’ was about motion, being on tour, about living life. And straight away he latched onto Rollo … rollocoaster, rolling, spliff, rolling, the long wheels turning. He just pulled all these things that were slightly connected together. And that’s how the album became Wooden Foot Cops on the Highway.”

During one such visit he was commissioned to compose the music for the 1990 Commonwealth Games opening ceremony.

Benny would remain UK- based until the late 1990s, though he returned to New Zealand intermittently. During one such visit he was commissioned to compose the music for the 1990 Commonwealth Games opening ceremony, a project he’s especially proud of. Another trip to the stereo ensues, and it strikes me how nothing in New Zealand in 1990 would have sounded so fresh. It’s a sonic history of New Zealand set to a backdrop of 909s and 303s. In the beginning birds sing. Then there’s the chants of Māori arriving before tribes form and they begin to clash. Abel Tasman arrives and four cannons blast, before the British begin to settle.

“The piece was called ‘Look to the Future / Kia Mau Ki To Māoritanga’ and I was going for the sounds of Aotearoa. I had to make a piece that 6,000 people could dance to that would also tell the story of New Zealand. It was inspired by samples of natural sounds like wind, waves, shells, and insects, as well as birds that Wayne Laird had made. I also drew inspiration from the Roy Ayers and Fela Kuti track ‘2000 Blacks’, particularly the idea of looking to the future but not forgetting the past, which I felt fit with the project. I had the line ‘look to the future but don't forget your past’ in English, and Temuera Morrison [cultural advisor on the project] translated that into kia mau ki to Māoritanga, which we both chant alternately at the end. It starts at about 122 bpm and it eventually finishes about 127. So you get this motion, and once you get the motion you can’t stop, and by the end 6,000 performers have made the Union Jack. It was a real buzz to see it evolve and be performed. I was playing live drums over my backing track of electro niceness and it was built on the swing of the Roland 909.”

Calling himself Pacific 909, Benny performed the piece live to a television audience of over 30 million people. But he felt let down by some of the more politically motivated responses.

“The feedback was confusing. Musicians seemed to like it, but the response from the political right shocked me. They said ‘there’s too much Māori in it’, and I was offended. And then the response from the left was ‘why did it end with the Union Jack?’ So the commentators created a division and I was caught in the middle. It was horrible. I just thought ‘what’s wrong with this country?’ Anyway the BBC liked it, and the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games creative people loved it. And I was so honoured to be commissioned to do it it.”

Discussing the music itself, I put it to him that what he produced might have gone over the heads of locals directly involved with the project way back in 1990. It transpires the audio engineers employed learned techniques otherwise unheard of in New Zealand at the time, and Morrison did not quite grasp Benny’s vision and approach until attending a rave many years later.

“I learned how to record watching Adrian Sherwood work with us, and he’d have sessions recording The Woodentops where he’d let all of us get on the desk. Actually when he came to New Zealand last time he said to his driver Harry the B ‘there’s two people I want to get a hold of. Dave Dobbyn and Benny Staples’. Harry took Adrian to see my good friend Cian at Conch [Records] and they found me. Anyway, the engineers at Mandrill were really excited, especially Roland Kileen, and they were such a great bunch to work with. So open to trying what I learned from Adrian Sherwood and other British engineers. I don’t think Tem [Morrison] quite got my approach at the time, but I saw him 10 years later and he’d been to a big rave overseas and he ran up and said ‘Benny! Benny! I get it now!’ [laughs]”

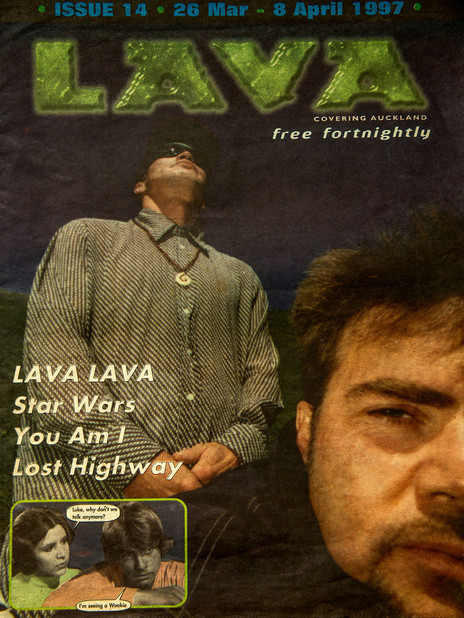

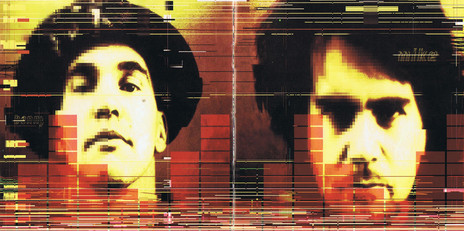

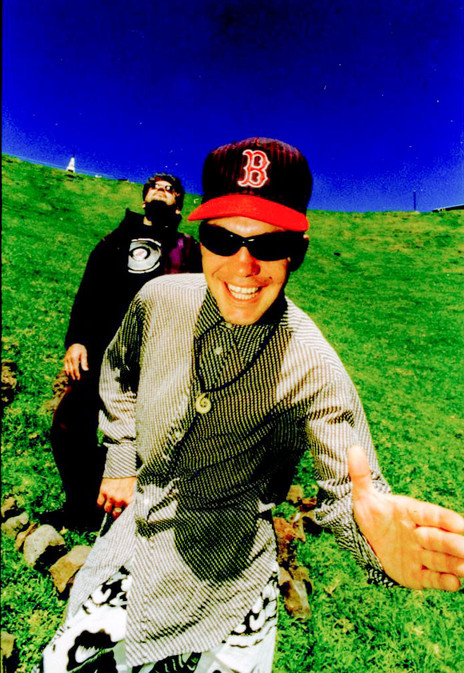

Back in the UK, Benny formed Lava Lava in 1994 with fellow expat Mike Nielsen. Described by Mixmag magazine as ‘shoe-shuffling space-age funk of truly flared-trouser proportions’, Lava Lava saw Benny on percussion, TR-909, and TR-303, with Nielsen live mixing and playing keyboard and guitar. Essentially electronic music for dancefloors with the added enjoyment of a dynamic live show [Benny would not sit while playing drums, preferring to dance while playing], the group quickly grew popular in the South London club scene, as well as playing well-received shows in New Zealand when electronic music’s popularity was burgeoning.

Benny is especially proud of the duo being accepted by the sometimes staunch South London music scene. “We got accepted as a South London group. Two Kiwi boys. People like T-Power just judged us on the music.”

“We are all equal on the dance floor.”

Perhaps acceptance was in-part a result of the ethos of the duo themselves. “We drew inspiration from Masters at Work. They are always inclusive. Which is what we were trying to do in Lava Lava. Be inclusive. Everyone is invited, rather than the mentality of some dance music people who want it to be exclusive. We were like, everyone can get into our music, and anyone is welcome. If you’ve got the right attitude come in, we don’t care who you are or what you look like. At the very beginning of Acid House there was an idea and a reality of equity culture. We are all equal on the dance floor, I loved this.”

Amidst the success of Lava Lava, Benny experienced a series of unfortunate events. In 1997, having just split up with the mother of his first born, he found out his own mother was terminally ill and would soon pass away. It is clear when hearing Benny reflect on this period, as well as is mother in general, how important she was in his life.

“She was a special person. Special firstly in that she was born with two holes in her heart, which if she’d been born only a few years earlier would have ended her. But she got one of the first open heart surgeries in Baltimore in 1947. The whole city of Palmerston North raised the money to send the sick girl on the boat, and the operation was a success. She lived life to the full, was the life of the party, and everyone loved her. And she drank and smoked like a true bohemian. She was a theatre director, a writer, an actress, and a painter. I got to spend time with her in the final days before she passed, and I was working on the fashion awards at the time. She kept asking me how that was going and insisting I finished the project despite her health.”

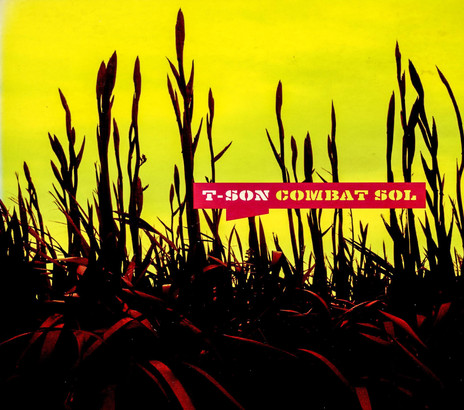

Benny returned to New Zealand permanently in 1999, and has since continued to DJ, produce, and perform music, as well privately tutoring in Matakana where he now resides. He has recently begun collaborating with his daughter Billie, and wrote and produced a solo album, Combat Sol (2004), under the moniker T-Son.

“I’m really into the regional aspects of music. That is why I called it the T-Son project, the sound of Newton. The sound of the bass in South London is special. West London gets all the props, but South London has the guts. The West Indians in London changed everything there, and then that spread out to us. The album was a challenge to myself. I wanted to see if I could write and produce something myself on a low budget. That was a really great experience for me. Finally getting full control of my music, which every artist wants. The engineer was really impressed too. He got me work on Soane’s album, and told him my work ethic was crazy. But I ran into some problems with life after the album, and at the same time the label the album was on folded. I didn’t know they were in trouble. So no one ever heard it. I’ve got some great reviews from magazines though. If anyone wants a copy they can write to me. Twenty dollar. [laughs]”

Benny’s main project currently is called Fever Co, though he has also been producing music with his adult daughter Billie on vocals. “We’re called b&B. Come to the b&B! She writes lyrics. She doesn’t sing. She sing speaks. She sounds like a way older soul. I really like it.”

He makes another trip to the stereo and we continue to chat. I ask, “Did she just say ‘black soul banana?’” He laughs. “I think so. Any weirdness I encourage greatly. Explore it. We don’t have to release it … it could be just for us and our friends.” More snippets of lyrics follow, and he’s right, her delivery style is captivating; a kind of haunting yet sensuous rhythmical spoken word.

As we listen to b&B, I reflect on how good every piece of music I have been played over the afternoon has been. I’m about to bring up that Duke Ellington quote before my thoughts are broken.

“You know the reason I agreed to do this interview is it because it’s with you. I’ve had a relationship with you based on friendship and music, and those are two of the most important things. The world needs more love. I wanted to tell you that because I’m doing life in reverse. Where most people get more secretive, I’m trying to be more open. I’m actually getting more radical too. Becoming more of an anarchist. But then I know we need the police. But the police need the criminals too. That’s Nietzschean.”