AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Gabriel Calcott

aka DJ Messenjah on Dubwize

When they weren’t gigging, he could often be found working on music in his home studio with Paul Bimler, the multi-instrumentalist, producer and DJ then better known as Confucius, or deepening his Rastafarian faith.

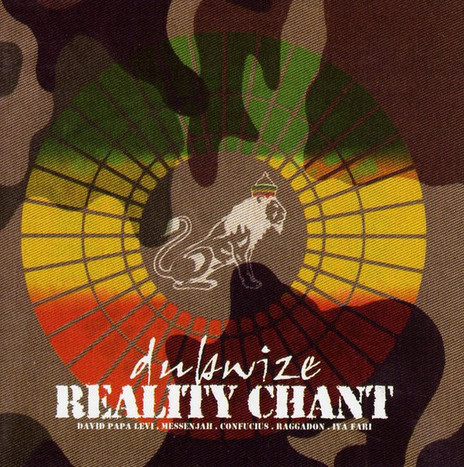

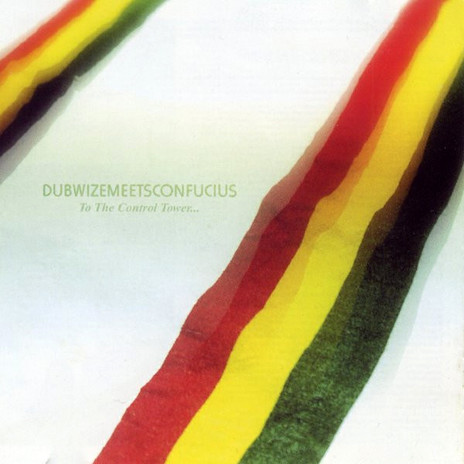

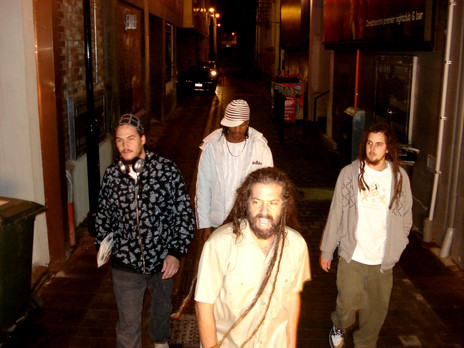

Over 20 years after Dubwize released their first two albums DUBWIZEMEETSCONFUCIUS: To The Control Tower… and Reality Chant on CD, both records have finally arrived on digital streaming services. If you attended outdoor raves or festivals in the South Island in those years, chances are you saw Gabriel and Dubwize winning over audiences with their pure-hearted messages, memorable melodies and heavyweight basslines.

Echo Records

From birth, Gabriel, the son of Darryl Calcott, co-founder of the South Island record store chain Echo Records, was destined for a life involving music. “I grew up around all sorts of music in the stores, but my dad was a big Lee Scratch Perry and Burning Spear fan, “ he says. “By the time I was twelve, I was listening to reggae, dub, and ragga artists like Shaggy and Shabba Ranks. My mates were like, what’s this stuff? But I was just vibing with it.”

Gabriel started going out to all-ages warehouse parties and outdoor raves around Christchurch and the broader Canterbury region in 1995. “I wasn’t a crazy teenager, so my parents trusted me,” he says.

One night, he went to a dance party on the Port Hills above Christchurch and was blown away by hearing DJs Geoff Wright aka Presha and James Meharry (Pylonz) play the sounds of early 1990s jungle/drum & bass on a big sound system. As a result of the musical education his father provided him with (“He was pretty well versed, loved Curtis Mayfield, James Brown ...”), Gabriel recognised that the music he was listening to was a mixture of sped-up soul/funk breakbeats, vocal samples taken from Jamaican reggae and ragga records, dub basslines and elements of acid house. “I was like, ‘Yo, this is it!’”

Inspired, Gabriel started spending his spare time in the Christchurch suburb of Sumner, where he would listen to and practise mixing jungle/drum and bass records with his friend, Jungle Jim. “Jim and his older brother Tobin had been DJing for a while, so they had a pair of belt-drive turntables at their mother’s house,” says Gabriel.

After he turned 16, Gabriel dropped out of high school, started working for his father at Echo Records, and began spinning records as DJ Specialist. His first big gig was at an outdoor party in Waimakariri River Valley called New Beginnings, where he played a well-received jungle/drum & bass DJ set.

A U-Turn

In 1997, UK drum & bass label No U-Turn released a compilation album called Torque that changed the genre’s direction, ushering in darker, tech-step, and neurofunk sounds. Around then, Gabriel’s father gave him his collection of Burning Spear records. Listening to those brilliant reggae and dub albums, Gabriel realised the reggae elements were what he loved about jungle/drum & bass. The techstep era wasn’t going to be for him.

“I sold all my jungle records and basically bought all the reggae records at Echo,” he says.

That summer, New Beginnings moved to Whitecliffs Valley, and Gabriel returned to the turntables there as DJ Messenjah. This time, he played a sunset reggae set to a few hundred people. Song by song, he found one of his callings, being a reggae DJ.

As the nineties drew towards a close, Gabriel started placing orders with the Californian record distribution company Ernie B’s Reggae and bringing Jamaican reggae, dub, and dancehall ragga vinyl to Echo Records. Between their reggae, hip-hop, and drum & bass sections, Echo Records became an essential stop for local DJs.

“Sometimes they’d be lining up and almost arguing over records,” he says. “I met most of the local music scene through Echo. People like Ladi6 would come in and hassle me for certain records.”

Outside of work, Gabriel’s fascination with reggae quickly pulled him into Rastafari, the religious practice and social movement that emerged in Jamaica during the 1930s. His gateways were listening to Bob Marley’s 1976 album Rastaman Vibration and spending time with Jungle Jim’s older brother Tobin, the first dreadlock-wearing Rastafarian he ever met.

“He had a lot of knowledge,” says Gabriel. “He used to talk about Rastafari and Emperor Haile Selassie, and he had a sleep-out with biblical passages relating to Rastafari painted on the walls. Even as a young fella, I needed to know more and went really deep with it.”

Roots’n’Riddim

Apart from Jim, Gabriel was also good friends with Redford Grenell, aka DJ Dreadford. One of the sons of New Zealand country music star John Grenell, Redford was a serious reggae head. Later, he became the original drummer in the live drum & bass band Shapeshifter. Periodically, Redford would get the call-up to fill in for DJs Bass Ace and Ruffian on Christchurch student radio station RDU 98.5’s Roots’n’Riddim show, and sometimes he’d bring Gabriel along. By 1998, Bass Ace had left Christchurch, and Gabriel became a regular host. Outside the radio, they ran regular reggae meets jungle/drum & bass DJ nights at Base Bar & Nightclub in the inner city.

In 1999, Gabriel organised a gig at live-music venue Dux De Lux with a DJ and two MCs who had been performing as Dread At The Controls: DJ Pops, MC Little Jah and MC DRed. “They were my introduction to seeing what Jamaican sound system culture looks like,” says Gabriel. “DJ Pops had a sampler loaded with dub effects. He was dropping the riddim [instrumental] sides of reggae and dancehall records, while Little Jah and DRed were toasting [rapping] over the top. When I saw them, I was like, ‘I want to do that.’”

Although there wasn’t much of a local reggae scene in Christchurch at the time, anytime Gabriel and Ruffian put a gig on, they’d pack the venues out. After a particularly successful night called Kings of Dub, Gabriel became very interested in promoting. “At that point, I couldn’t quite believe I could make money as a DJ,” he admitted.

The following year, Ruffian proposed renaming the Roots’n’Riddim show, suggesting they call it Dubwize. After Gabriel agreed, they ran a couple of shows as Dubwize Sound System and took a booking at The Gathering festival on New Year’s Eve. “It was a different vibe back then,” he says. “The audiences that came to our shows would really soak up the vibe of the music. At festivals like The Gathering, it wasn’t really about drinking. That all came later on.”

Dubwize

In 2000, Ruffian left Christchurch to accept a job offer in Auckland, and Gabriel took over Dubwize full-time. Around the same time, Justin Rahui, aka Little Jah, moved to Christchurch. “I was getting offered lots of gigs, so I asked him if he wanted to come and MC with me,” says Gabriel. “That was the beginning of Dubwize performing with a vocalist.”

Not long after, Andrew Penman from Salmonella Dub invited Dubwize to play two shows with them and Ladi6 in Christchurch and Dunedin. “Little Jah had the crowd in the palm of his hand in Dunedin,” says Gabriel. “It was the wickedest performance. That was what launched Dubwize into a bigger world.”

The following year, Gabriel’s friend Nik Adams, aka DJ Dreadknowledge, came into Echo Records and gave him a copy of MC David Papa Levi’s self-released debut EP. Originally from the San Francisco Bay Area, David was a longstanding reggae vocalist associated with the New Zealand chapter of The Twelve Tribes of Israel Rastafarian organisation. “Nik had DJed for him and said he was amazing,” Gabriel enthuses. “I invited Levi to come down south to play some shows, and we went on a mini-tour with him and Nik.”

On the first night of the tour, when they performed at Dux De Lux in Christchurch, David won over the audience effortlessly. “He got an amazing response. It felt really powerful. At that point, I knew I wanted to work with him.”

In David, Gabriel didn’t just find a vocalist but also a mentor. “I saw him as a Rastafari elder,” he says. “I learned a great deal from him. We were both on a mission to live it, and neither saw this as a part-time thing.”

Building Riddims

While laying the foundations for Dubwize, Gabriel became friendly with local music producer, DJ, and multi-instrumentalist Paul Bimler, aka Confucius. “He brought some copies of his first EP into Echo Records in around 1999 or 2000,” says Gabriel. “There was this one dub track on there, and I was getting interested in the idea of music production by that point, so I asked him if he wanted to make a dub tune with me.”

The first time they got together in the studio they recorded a riddim called ‘Roots Philosophy’. Fittingly, the first time David came down to Christchurch to perform with Dubwize, he tracked a vocal over it. “It blew our minds,” says Gabriel. “We didn’t know what we were doing. We just tried to make reggae and made a wicked riddim that [David Papa] Levi put vocals on.”

In 2001, Gabriel studied music production and audio engineering at the MAINZ (The Music and Audio Institute of New Zealand) campus in Christchurch. Assisted by his parents, he purchased some studio equipment from one of his tutors. “He sold me all the microphones, a 24-track desk, studio monitors, and heaps of outboard gear,” Gabriel said.

While Gabriel was learning his way around the gear, David became an official member of Dubwize. From there, Gabriel, Little Jah, David, and Paul felt ready to take things to the next level. “After that first track with [David Papa] Levi, we put together four or five more demos,” says Gabriel. “Thanks to Echo Records, my dad knew all the New Zealand record label reps and helped us send out a demo.”

To The Control Tower

Gabriel remembers Festival Mushroom Records offering them a production and distribution deal almost overnight. “They didn’t muck around,” he says. “They just came straight back with an offer.” After flying to Auckland for a meeting, Dubwize signed a contract and finished recording their debut album, DUBWIZEMEETSCONFUCIUS: To The Control Tower…

The album consisted of songs fronted by Little Jah or David, dub instrumentals, and a guest feature from Aaron Retimana, aka MC Mana, who recorded an improvised dub track with them, ‘Aotearoa Dub Connection’. Near the final stages of the process, Gabriel befriended a young African Rastafari Iya Fari, who played percussion on some of the music. He also began MCing with them on stage at shows.

In March 2002, Confucius and Dubwize Soundsystem’s track ‘Contemplation Dub’ was featured on Fine Tuned, a stylistically diverse compilation CD of contemporary Christchurch presented by The Package gig guide. Eight months later, their debut album hit record store shelves nationwide. “We got some pretty good coverage and sold about one thousand copies,” Gabriel says. “Afterwards, we were inundated with gig offers. We must have played hundreds of shows during those early years.”

In the wake of DUBWIZEMEETSCONFUCIUS: To The Control Tower… Dubwize played a gig at Jetset Lounge in Christchurch with Dunedin dub reggae band Zuvuya. After they performed, he found himself in an exciting conversation with a visiting tourist from the Caribbean.

“I thought, who is this outspoken bro?” he says.

Not long after, MC Mana gave Gabriel a call. “He said he’d met this Rasta MC from the Caribbean and wanted to bring him to our studio,” says Gabriel. When they turned up at the studio, Gabriel recognised the Rasta MC from the Jetset Lounge.

Born in Montserrat and based in London, Lyndon White, aka Raggadon, wasn’t just an MC – he was also a serious percussionist. “What really blew me away about Raggadon was his Nyabinghi drumming,” says Gabriel.

Associated with the Rastafari faith, Nyabinghi is a form of drumming and chanting that dates back to the 19th century. “My studio was next to my parents’ vegetable garden. One of the first times he came up, he took a djembe out into the garden and started playing it. He looked like he was in absolute heaven.”

Growing up on the Caribbean island of Montserrat, Raggadon was exposed to Rastafari from a young age. He spent his days helping his family grow fruit and vegetables and, in his leisure time, deepened his relationship with Rastafari through music. “I’d actually describe him as a master Nyabinghi drummer,” says Gabriel. “After he introduced me to Nyabinghi, we started practising it and added it to all of our recordings.”

Reality Chant

By this stage, Gabriel and Paul were pumping out new reggae, dub, and dancehall riddims in the studio. Naturally, they wanted to create another album, so once Iya Fari and Raggadon entered their orbit, they started recording songs with them, as well as David, Little Jah, and MC Mana. “Buying all that recording gear really sped up our production process,” says Gabriel. “When I listen back over the albums, our second album sounds so much better.”

In December 2003, Festival Mushroom Records released Dubwize’s second album, Reality Chant. Instead of billing it as Dubwize Sound Meets Confucius, they simply opted for Dubwize. By this stage, Gabriel and Paul had become a well-honed production unit. “He’d play most of the instruments and arrange the horn parts for session players like Isaac Aesili and Simon Kay,” says Gabriel. “I’d make the beats and handle the production.” It’s a musical working relationship that endures between the two friends to this day.

Gabriel counts their years working with Iya Fari and Raggadon as his favourite period in Dubwize’s history. “It was a multicultural group,” he says. “We all had different whakapapa and connections, but we came together with a common unity. When you listen to Reality Chant, every track addresses cultural issues, corruption, and tries to wake the people up. The message we were putting out then is actually even more relevant now.”

Follwoing the release of Reality Chant, Dubwize performed at most of the major outdoor festivals operating around New Zealand at the time: Kaikoura Roots, Raglan Soundsplash, Destination, Alpine Unity, Rippon, and Parihaka. They also scored support slots for Lee Scratch Perry, Mad Professor, Dub Syndicate, Fat Freddy’s Drop, The Black Seeds, Salmonella Dub, Blindspott, TrinityRoots, Solaa, and Scribe. Over the following years, Iya Fari, Raggadon, and Little Jah departed from Dubwize for personal reasons, leaving Gabriel, David and Paul to keep flying the flag. “As the group got smaller, things got more challenging, which put more pressure on us,” says Gabriel.

The Sojourner

In 2008, they regrouped to launch David’s solo album, Dubwize presents Snypa Levi – The Sojourner, this time released through their own production company and record label, Reality Chant Productions. On release, the website Niceup Aotearoa Reggae wrote, “The album is tight. The riddims are top-ranking.”

Around the same time, Gabriel began to fulfil his long-held dream of working with Jamaican reggae and ragga vocalists. Serendipitously, ‘Country Living’, one of the riddims he’d produced for The Sojourner, became his entry point into the Jamaican scene. After locking in a deal with the Jamaica-based record distributor One Love, he was able to cut several different vocal versions over ‘Country Living’ with David and the Jamaican vocalists Chrisinti, Ginjah, Jah Mason, Luciano, and Mikey General for worldwide release as 7" vinyl records.

Kings Highway

Two years later, in 2010, Gabriel released a reggae compilation album, Kings Highway, through Reality Chant. Featuring music he’d created with Bimler and vocals recorded by a range of artists from New Zealand, Jamaica, and further abroad, Kings Highway represented a substantial accomplishment for Gabriel. In a testament to this, in 2011, the United Reggae website noted that his riddims were fast making a name for themselves worldwide.

Over the following decade, Gabriel continued to record and produce Rastafari-focused reggae music with a range of artists from here and abroad.

During the 2010s, he spent a stint working as the music programing director at the Christchurch student radio network station RDU 98.5 FM. He also co-founded the Bass Factory Sound System with DJ Gooba and took an active role in local sound system culture.

In more recent years, he’s been living in Little River outside of Christchurch, where he spends his days gardening with his family, homeschooling his children, making music, and participating in the Waikirikiri Kōpuni Taonga Pūoro collective Kiki Pounamu. As he told the United Reggae website, “When I began, Rastafari was a part of reggae music, now reggae music is just a small part of Rastafari. I try to live Ital, read my bible every day, hail The King.”

Reality Chant Productions

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air