AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Denver McCarthy

aka Micronism, Mechanism, Chaos Reader, DJ Vraj, Pedestrian, Liquid Water

Before the decade was out, McCarthy had recorded two classic albums, his industrial techno debut Morningstar (1994) and his Independent Music NZ Classic Record-winning dub techno opus Inside A Quiet Mind (1998). In the process he served as a guiding light for New Zealand’s electronic music scenes.

In 1999, McCarthy joined the Hare Krishna faith and embarked on a new adventure that took him to South America for several years before he settled in Brisbane. His story is a sequence of life-changing moments, and the chaos and calm he found between them.

Early years

“I was born in Tokoroa, but we moved to Auckland when I was four or five,” says McCarthy, speaking via Zoom from his home in Brisbane. “Interestingly, I don’t have a single memory of Tokoroa.”

Growing up in what he described as “a conservative Christian Polynesian family” in Mount Roskill in the 1980s, McCarthy remembers that music was always there. When he was eight, his older brother borrowed a Casio synthesiser from school and brought it home. “I have this very vivid memory of playing with this thing for hours,” he said. “I thought it was really cool.”

McCarthy was blown away by Paul Hardcastle’s ‘19’. “It was electronic and full of samples.”

Around the same time, McCarthy saw the classic 1984 American hip-hop dance drama Beat Street at the cinema and was captivated by the music, the fashion sensibilities, and breakdancing depicted in it. “It influenced me so much,” he says. When he heard British electro musician Paul Hardcastle’s anti-war anthem ‘19’ a year later, McCarthy was equally blown away. “It was electronic and full of samples,” he said. “Strangely, it went to number one in New Zealand and loads of other places.”

In 1987, McCarthy started playing acoustic guitar during his first form year. As soon as he could work an afterschool job, he started saving money to buy an electric guitar. “I had a high school band [called Blueprint],” he remembered. “Later on, I was in a heavy metal band called Power Jelly.” The metal band’s second guitarist and de facto leader, Josh Wulf, was the first person McCarthy met who became a Hare Krishna devotee. “He was the one who organised all the gigs and practices,” says McCarthy. “He was the main link when I got involved later on.”

Discovering dance music

In the early 1990s, McCarthy started going out to nightclubs while he was still in high school. “We were all using fake IDs,” he recalls, laughing. The first dance party he attended was a rave organised by DJ Sample Gee at DTM (Don’t Tell Mama) on Karangahape Road. “It was just pumping,” McCarthy says. “Everyone was smiling, happy, and dancing. I just thought, ‘Wow, what is this? How can I get more involved?’”

McCarthy began visiting record stores, including Truetone Records in Takapuna on Auckland’s North Shore. There, he struck up a friendship with a record clerk named Alec Coleville, who was paying close attention to the emerging sounds of underground US and UK dance music. “He was an important piece of the puzzle,” says McCarthy. Coleville would slip him copies of a photocopied black and white rave zine from New York called Under One Sky. “Each issue had a bunch of reviews of new tracks, maybe an interview or two, and some advertising for record stores,” says McCarthy.

Halfway through his sixth form (year 12), McCarthy dropped out of high school. “I’d just had enough of it,” he says. “I didn’t do university or anything like that, but I had a part-time job at Kingsley Smith’s music shop. They just really treated me like one of the family and helped me a lot.” Kingsley Smith was also a short walk from a Hare Krishna restaurant that McCarthy would visit regularly at lunchtime. Back then, the drawcard was a cheap vegetarian meal. Later on, that would change.

When he wasn’t working at Kingsley Smith, digging through record store bins, or attending dance parties, McCarthy kept himself busy producing electronic music in a makeshift home studio. “There were a lot of classic drum machines and Roland keyboards going around at the time,” he says. “People were getting rid of them and moving onto the new digital technology that was arriving at the time.”

in Auckland’s rave scene, McCarthy found a niche inside a niche

After spending some time in Auckland’s rave scene, McCarthy found a niche inside a niche. At first, he’d been exposed to lighter, more melodic dance music. While attending parties and listening to records, he began meeting a group of guys from Hamilton who were exploring the crossover between techno, industrial, jungle/drum & bass, and ambient music. “It was darker, faster, and harder-edged,” he said. “Being from a metal background, I thought, ‘Okay, this is where I should be.’”

One of McCarthy’s key connections within that crew was Jared Sims, aka DJ J Red. “I consider him one of my gurus,” he says. “He can just pick a genre before it becomes big. He’ll be listening to stuff that no one else thinks is very interesting, and then three months later, they’ll all be into it. Having people like him around gave me all the influences that allowed me to do my thing.”

Mechanism

In terms of releasing music, McCarthy got his first big break as a 17-year-old when New York house/techno pioneer Leonardo Didesiderio, aka Lenny Dee, came to Auckland to play a DJ gig at The Box on High Street. “I took my DAT [digital audio tape] player down with the idea I would play him some music,” says McCarthy. Didesiderio liked what he heard and offered to release some of McCarthy’s music on his IST Records hardcore/gabba label.

In 1994, IST Records released a three-track 12" vinyl EP from McCarthy under his first electronic music alias, Mechanism. That same year he met multimedia artist Mike Weston, who was co-running a record store, art gallery, recording studio, and alternative video rental library called Cyberculture with Heath Burgoyne.

Weston was also in the process of setting up a short-lived techno label called Pulse Records. The first release was a New Zealand techno compilation album titled Harmonic 695, which features two of McCarthy’s Mechanism tracks and ‘Viaduct’, a song he recorded with Weston, as Pedestrian. “After the compilation, the idea of me doing an album came up,” McCarthy recalled. “I was just writing music all of the time. That was my thing. I had no idea whether it was going to be released or not. I just liked making it.”

When Weston offered him the opportunity to record a Mechanism album, McCarthy drew from his experiences with heavy metal, psychedelic drugs, and the Christian faith to dream up an industrial techno concept record called Morningstar.

Morningstar

Written and sequenced on a Korg 01/W workstation synthesiser, Morningstar saw McCarthy reimagining his musical background and upbringing in alignment with the hard futuristic sounds he’d fallen in love with. In the process he churned out 10 hurricane-sized industrial techno tracks.

“Every Māori and Pacific musician of a certain age has a rock or metal pedigree” – Mokotron

As Māori electronic music producer Mokotron puts it, “Every Māori and Pacific musician of a certain age has a rock or metal pedigree: so many from that era got their start in metal bands. Morningstar is the sound of a Samoan kid from Avondale College unplugging the guitar from their Metalzone pedal and plugging in a TR-909 instead, without changing the gain settings.”

In the wake of Morningstar and his first release on IST Records, McCarthy had the opportunity to travel around New Zealand, and also to play at significant dance parties of the era in Wellington and Christchurch.

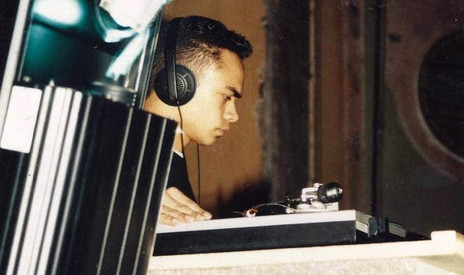

At first, he would perform by presenting his music off a DAT player. Later on, as frontloading CDJs arrived, McCarthy began playing DJ sets. “I was playing a lot of gabba and hardcore techno,” he said. “I enjoyed DJing, but I didn’t devote enough time to it. I was more interested in creating music.”

In the ninth episode of Muzic.net.nz’s Distorted Transmission podcast, host Will Stairmand recounted visiting McCarthy at home and hearing him leave short fragments of music on loop for hours. “I used to leave it on the burner and see what comes to mind,” McCarthy told him. “You jam out for a bit with loops, and then if something sticks, you gradually create an intro, a middle, a peak and an end.”

In 1996, IST Records released several tracks off Morningstar as a 12" vinyl EP. The following year, McCarthy contributed a track titled ‘Terrible Purpose’ under the Chaos Reader alias to AK97, a compilation album of late 90s Auckland electronica that paid homage to the classic Auckland punk compilation, AK79. “Like I said, I was making lots of different types of music, and not all of it sounded like Mechanism,” he recalls. “So I ended up changing my artist name when I put music out.”

Kog Transmissions

Around when AK97 came out, McCarthy met Chris Chetland from the then newly formed Kog Transmissions collective through the warehouse parties held at 398 Great North Road in the late nineties. When they realised they lived just down the road from each other, Chetland and the extended Kog family quickly welcomed McCarthy into their world. “I remember them helping me edit some of my music free of charge,” he says.

Chris Chetland and the extended Kog family quickly welcomed McCarthy into their world

“The scene was changing from us as a group playing 180 BPM, dark, distorted stuff, to the more refined Detroit techno sound of artists like Jeff Mills and Underground Resistance,” says McCarthy. Accordingly, he started producing music in a similar vein, using utopian melodies, futuristic drum rhythms and lush synthesiser pads to create a sound that was beautiful but gently tinged with sadness. In the process, he presented a localised naturalistic perspective on the space-aged machine funk sounds that emerged out of Michigan in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

When Chetland heard McCarthy’s reinvigorated techno music, he asked him to record an album for Kog. Unsurprisingly, McCarthy accepted the offer. “Kog let me do whatever I wanted,” he continued. “I was always making music, so it was just a case of going through my catalogue, picking out some music that would fit together nicely, and thinking up a concept.”

Micronism

In 1998, a 21-year-old McCarthy brought everything he was thinking about together as his Inside A Quiet Mind album, recorded under a new alias, Micronism. “I was getting into meditation more deeply and starting to tinker with some spiritual ideas. It was strange how the album kind of foretold something about my future.”

Nine years later, in his book Soundtrack: 118 New Zealand Albums, Nelson-based journalist and critic Grant Smithies described Inside A Quiet Mind as “The best electronic album ever made in this country.” In his words, “The man has a rare gift for coaxing warm spirits from cold circuitry, which is why Inside a Quiet Mind gets inside you, soothing your soul and reaching deeper emotional places than any other local electronic music to date.”

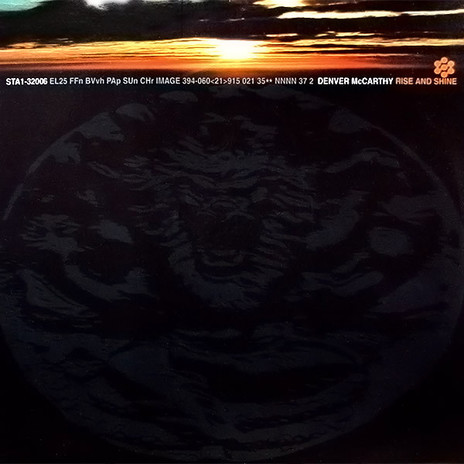

In 1999, McCarthy released an EP of Micronism material titled Steps To Recovery through Matt Drake and Simon Flower’s New Zealand techno label, Nurture. He also released an album under his own name called Rise And Shine via New Yorker Dave Tomaselli’s Statra Recordings and a collection of abstract downbeat and ambient jams he’d recorded in 1995 with fellow producer Ben Harris aka System/Nebulus as Liquid Water.

Amid this burst of releases, McCarthy was drawn towards fully exploring his growing interest in the Hare Krishna faith. “I don’t know what happened,” he continued. “I had this Hare Krishna record with the founder of the movement, Srila Prabhupada, chanting on it. I just remember there was a period when the only thing that was of interest to me was listening to that Krishna record. I guess quite quickly I lost my taste for listening to techno music and going to parties.”

After falling out of love with electronic music, McCarthy sold his studio gear and gave away his records. He moved to Australia to live with his parents in Brisbane, where he applied to study music at the local conservatorium. “I was kind of on the fence about what I was going to do next,” he said.

When the conservatorium declined his application, McCarthy had a conversation with one of the local Hare Krishnas. As it turned out, McCarthy’s old metal bandmate Josh Wulf had established an ashram in Wellington. The Krishna felt that McCarthy might be able to move there, live in an ashram environment, and immerse himself in Hare Krishna meditation and philosophy. “I went to Wellington, lived in the ashram for about a year, and then in 2000, we went to South America to live in Lima, Peru, for three years.”

South America

In the early 2000s, McCarthy spent time at several different Hare Krishna ashrams and temples in Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia. He spent his days meditating, singing, dancing and performing acts of service, like working in the centre kitchens. “Everyone’s gotta eat,” he said. “Also, Hare Krishna is the kitchen religion.”

McCarthy was fascinated by Kirtan: Hare Krishna meditative call-and-response chanting

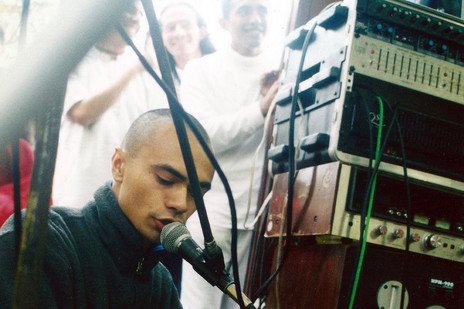

What really caught his attention, though, was Kirtan, a form of meditative call-and-response chanting the Krishnas practised daily. In those repeated ancient mantras, McCarthy found a constantly renewing connection to something deeper. “The spiritual aspect of this sound experience makes it fresh every time you do it,” he explains. “The more I get into it, the more I realise the external musical elements matter less and less. It’s about the presence you bring to it.”

While living in South America, McCarthy procured a multi-track recorder and Korg drum machine/synthesiser. In his spare time, he started making music that mixed devotional kirtan mantras with electronica under the DJ Vraj alias. “There was a utility there,” he says. “The music was intended to give Hare Krishna youth something to keep them occupied. If you listen to it, it’s fun. It’s not deep or anything.” Later on, McCarthy’s friend DJ James Chesterman released several of his DJ Vraj projects through his POSITIVE Dance Music label.

In 2004, McCarthy returned to New Zealand and spent a year in a Hare Krishna temple in Christchurch. After Christchurch, McCarthy relocated to Brisbane, where he now lives with his wife and young son, works in a Hare Krishna restaurant and runs Kirtan chanting workshops around the city. “We have Kirtan every day at the temple, but I’m part of a team that organises Kirtan for people who would never go to the Hare Krishna temple. We do these nights where we present Kirtan as a musical, meditative healing experience.”

Inside A Quiet Mind

In the late 2000s and 2010s, record labels from America, the Netherlands, and New Zealand, including IST Records, Delsin, and LOOP Recordings Aot(ear)oa, started approaching McCarthy about reissuing his Mechanism and Micronism music, culminating in Inside A Quiet Mind finally being pressed on vinyl, just shy of two decades after it was originally released.

‘INSIDE A QUIET MIND’ RECEIVED THE INDEPENDENT MUSIC NZ CLASSIC RECORD IN 2023

When Inside a Quiet Mind was reissued, leading electronic music website Resident Advisor described it as “a record that captured a life in transition” while noting that “the past two decades haven’t robbed it of its quiet power”. “I saw that reissue as the universe, Krishna, whatever, reminding me of the importance of having, keeping, meditating on the quiet mind,” says McCarthy.

Six years later, Inside A Quiet Mind was awarded the Independent Music NZ Classic Record as part of the Taite Music Prize 2023. At the ceremony, Chetland introduced McCarthy with a speech contextualising the album as a high watermark moment within Aotearoa’s burgeoning late 90s dance music scene. Afterwards, McCarthy took to the stage with his son in tow, gracefully thanking his family, friends and community for their support and love before getting everyone in the theatre up and dancing to a short but euphoric Micronism performance.

“I’m made of the kindness of all these people I’ve mentioned,” McCarthy said, concluding his speech. “A flower grows because of the environment it is given, and because of all of these people, I feel so grateful and indebted. This reward will serve as a reminder to their kindness upon me. Thank you so much.”

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air