Kāren Hunter, still only in her early 30s, already had quite some career when that album came out, distilling her interests and experiences into songs notable for their musical diversity.

The album won wide critical acclaim, however that diversity was too much for some in the music industry which, by then, she had worked in for decades.

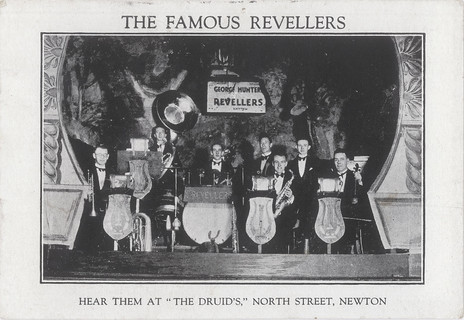

Kāren Hunter was born into a musical family: one grandfather was a pianist who ran brass bands; a grandmother a music teacher in West Auckland; her trumpeter father Keith and clarinettist mother Dale met in the National Youth Orchestra,

“Actually I was in the National Youth Orchestra, carried [in utero],” she laughs.

The other feature of Hunter’s long career also came from her parents: both were disciplined and organised, her mother representing musicians in union meetings, becoming a facilitator, published author and starting Zenergy Global, a facilitator training programme founded in 1993 which works with business and community leaders here and in Australia.

Her father went into the media, became an investigative journalist for the NZBC (as it was then), directed documentaries and some drama, and authored books about the Scott Watson and Arthur Allan Thomas investigations.

So both were high achievers and orderly?

“Oh yes. Every day it was ‘Brush your teeth, do the dishes, put out the milk tokens, do your practice.’ That was what you did.”

Hunter learned violin at age three, then clarinet and piano. But when she got up the courage to tell her mother she no longer wanted to play piano – which she hated – her mother accepted it quietly ... then after a telling pause asked, “So Kāren, what do you want to play?”

“That was first time I said the word ‘guitar’. I started lessons on my ninth birthday and continued until I was 15.”

She learned from, and performed with, the classical guitarist Ross Hill (brother of writer, film director, editor and producer Keith Hill) and they began writing songs from Keith’s poems, played venues like Café Real in the late 70s and for three years performed at the many acoustic venues then in Auckland’s city centre.

But Hunter was inhaling all kinds of music, under the blankets at night with her transistor radio then from a bedside turntable.

“Lou Reed’s Rock and Roll Animal on the headphones at 3am. Bowie’s Pin Ups or Horses by Patti Smith, those albums were so progressive and so symphonic I would just get right into the sonics, every nuance and the atmosphere.”

Reed, she says, taught her what it was like to take heroin without actually having to do it.

It’s instructive to hear what she was listening to at that formative age of 14: “Lots and lots of Hendrix, I was a big Bowie fan, Joan Armatrading, Nick Drake, John Martyn, the Stones.

When Hunter recounts a litany of formative influences it’s easy to understand why her own music is so diverse.

“I always liked the Beatles but they didn’t grab me by the throat like the Stones did. There was Blood Sweat and Tears with all the horns. I skipped [Metro College] seven times to watch the movie Hair, similar amount of time to see The Last Waltz and Jesus Christ Superstar, I’d grown up seeing opera so those appealed to me to understand the feel and power of rock music.

“Then later Queen, Slade, The Fall, Ian Dury ... ”

When Hunter recounts this litany of formative influences it’s easy to understand why her own music would hardly conform to genres and why, two decades later, The Private Life of Clowns should be so diverse.

But there was even more – more playing, traveling and organising – between teenage years in the 70s and recording in the late 90s. She was in the band Green Eggs and Ham, then joined a PEP scheme in Mangere teaching street kids how to play and present their music. She says she “lucked into” a band with two members of the emerging Ardijah (drummer Richie Campbell, guitarist John Diamond) with future actor Jay Laga’aia as the band’s singer.

“When Ardijah started to get more work those two left and were replaced by Ara Mete and Pihana Tahapihi from Billy TK’s backline. Amazing musicians, and we played on marae and in prisons and pubs, we were learning how to perform. The band was called M.A.D. Scheme (Mangere Arts Development Scheme).

However, in 1983 at age 18 she went on the well-worn path to Sydney where she played solo gigs but also signed to an agency as a backing vocalist. She was assigned a band, Sensational Tigers, which played covers on the RSL club circuit.

That was formative in another way. The group had proper PAs and sound engineers so she learned about live sound and production, and professionalism because the agency ran a tight ship: turn up on time, rehearse, sound check ...

She formed Plastic Smiles with Australian bass player and producer Pryce Surplice, playing original material but in 1987 left Sydney for London where, for four years, she played guitar and sang at open mic nights, tentatively at first but finding her niche because, despite all the band work, “I’d always considered myself a songwriter”.

Towards the beginning of the 90s she was back in Auckland where the Ponsonby café Java Jive was pumping.

“I’d get up and have a bit of a jam, but it was a very masculine scene. There were a few women, just Truda Chadwick, Trudi Green, Beaver, and Kim Halliday. But the one I was most taken by was Leraine Horstmanshoff, a multi-instrumentalist from Utah who played bamboo sax, flute and didgeridoo.”

Together they formed Spinning Wheel in 1992, toured the country in 92-93, played the orientation circuit – usually in the women’s spaces – went to the Michigan Womyn’s Festival, and played other dates in the US and Hawaii before returning to New Zealand.

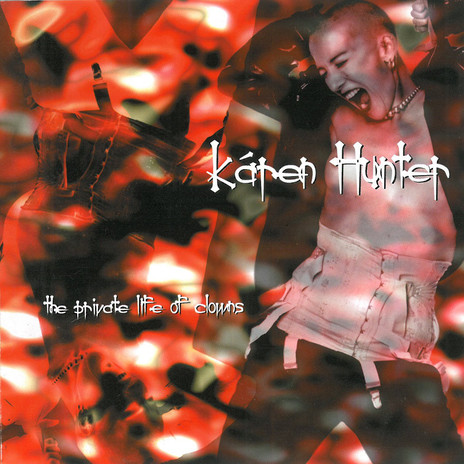

After Horstmanshoff returned to the States in the middle of the decade, Hunter was approached by Java Jive to organise a weekly women’s night. That was the very successful Raw Fish Salad which ran for two and half years, only stopping when Hunter decided to record her own album, The Private Life of Clowns in 1998.

When it was finished she shopped it a little but “I was told [by an Australian company] the album was unsellable because it was too diverse,” she says, laughing.

“I’d grown up on Bowie so I couldn’t comprehend that!

“I was told if I wanted to be successful, I needed to streamline everything, the sound, the instrumentation, the image, the photos. There wasn’t even a possibility that I could have done it! I couldn’t do it, I couldn’t do the industry. No judgement about people who can, it’s fantastic they can get their music out there and I get to hear it. But I just wasn’t able to do it. No, no, no.

“I didn’t play in a genre because I didn’t know how to, and didn’t really have an appreciation of genre.”

“I didn’t play in a genre because I didn’t know how to, and didn’t really have an appreciation of genre. It wasn’t conscious, ‘Perfection/Washing’ [on the album, with Horstmanshoff on bamboo sax] was very symphonic using the instruments I had to work with.

“‘Angelfish’, my one and only single-cum-video, was quite different, very well produced by Charles Bracewell and and Richard Huntington [of 95bFM at the time] and was quite commercial. I was grateful for the song, but it had nothing in common with anything I’d done before … or since.”

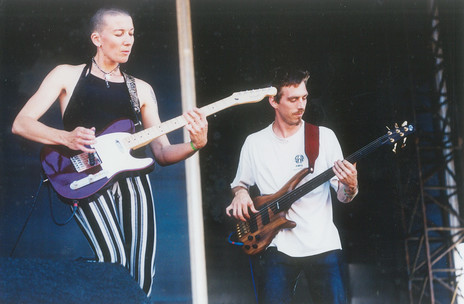

The album marked another turning point in her career. By the late 90s – inspired by Boh Runga in Stellar* – she’d gravitated back to the heavy rock she loved as a teenager and even played bass in a glam-rock band. There was the band Love Mussel with guitarist Alan Gibbons, Matthew Hunter on drums and bassist Willy Seiffert, and ‘Angelfish’ remixed by Baitercell at Kog Transmissions.

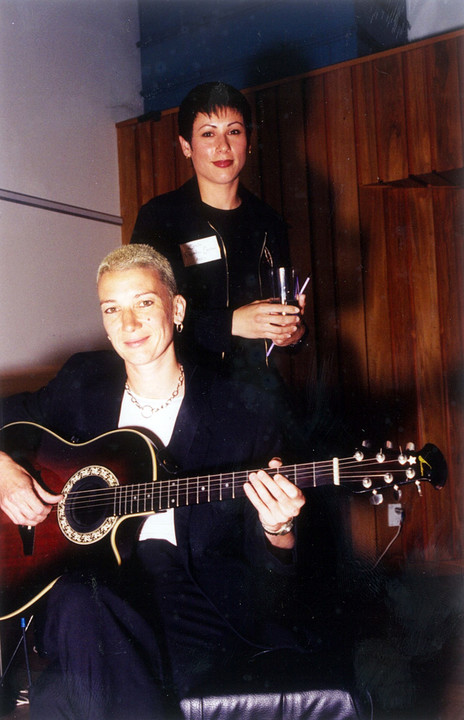

This was a period of peak Hunter: she was profiled in the Sunday News by Mike Alexander whose opening sentences were, “Kāren Hunter has presence. The first thing you notice is the tightly-cropped hair. It gives her an aura of fearlessness.”

The Private Life of Clowns was reviewed favourably in Pavement: “If you’re expecting folk feminist catch-cries, girl-power or wimmin-weaving you’ll be disappointed. Hunter isn’t fitting into any boxes and there’s plenty her to suggest she deserves chart and cafe success ... highly recommended.”

In Real Groove, Chris Bourke weighed in with “this gem deserves a much better fate than languishing in any limiting genre such as women’s music” and in the NZ Listener Nick Bollinger also addressed the issue of “the term ‘women’s music’” which had hidden some fine performers like Hunter, “one such secret star”.

With her festival, cafe and club performances – as well as opening for the likes of Ani Difranco, Suzanne Vega, Tony Childs, Hello Sailor, Paul Ubana Jones, Beverley Martin, Julie Felix and others – by the close of the 90s Hunter seemed poised to become a very big name.

“But by end of 2000 I’d turned 36 and that was it, I’d done it all this stuff, but what else to do? I was despondent and disillusioned. I could leave music or go deeper.”

As if anticipating the passing of one period of her life and the start of another, she released the double CD Inside Outside in 2001; the first disc comprising mostly live solo recordings in cafés and venues such as Auckland’s Temple, the second is live with her band of guitarist Al Khan, bassist Seifert and drummer Nannette Fortier.

In New Zealand Musician Mahinaarangi Tocker said “this recording is brave, solid, beautiful, sad, happy and strong ... Kāren Hunter can rock it, reggae it, folk it, funk it and jazz it with the best”

Gary Steel in Metro wrote of the “ridiculously accomplished guitar-playing, singing, songwriting Aucklander whose songs are pithy, compassionate and insightful”. In Rip It Up Bronwyn Roundtree said “songwriting this good cannot be faked”.

Hunter’s

‘Inside Out’ album was a summing up of her folk and rock personae.

At www.elsewhere.co.nz, I wrote, “Hunter has one of the most sensual voices in the country – full of swoops and power – and she addresses sex and sensuality with refreshing passion. She’s also a dynamite guitarist: check out her acoustic work on ‘Love’s Good Eye’, full of chimes and stops, or the physical instrumental ‘Kokee’.”

Inside Outside was a summing up of her folk and rock personae as she accepted a position at MAINZ teaching guitar and voice. But some of the students knew things about music she didn’t know, “and they were 18. They could sing intervals, knew the Dorian scale, and so I decided to enrol as a student at MAINZ while also teaching there”.

And another avenue revealed itself, that of academia which she had rejected when she quit school. So she enrolled at the University of Auckland in the School of Music and went straight into the second year of their new pop music course, “but at the end of the year I realised all the people I wanted to play with were in the jazz programme”.

She did a split degree, starting as a first year in the jazz course and continuing with the pop course.

Her jazz tutors opened her up to other worlds of music, arrangement and writing beyond what she’d learned by doing: “I did guitar with Martin Winch who was huge influence, one of the most amazing people to learn music from, he had so much love for harmony. He could hear what I was trying to do and would gently coach me.”

There were also guitarists Neil Watson and Lance Sua, saxophonist Roger Manins teaching improvisation, trumpeter Nevile Grenfell, and drummer Ron Samsom, all inspiring because they were also players.

And along the way there was her music-cum-poetry album, Mr Kite Goes Fishing in 2004 with numerous jazz, pop and rock contributors.

After graduation Hunter returned to academia and wrote and recorded her 2007 album Rubble for her Honours where the brief was to do a New Zealand version of what Tom Waits and Rickie Lee Jones had been doing at the intersection of jazz, poetry and pop.

Among the large cast were bassist Aaron Coddell, Samsom, Manins and pianist Stephen Small. In the liner notes I acknowledged the “boho gestures of early Rickie Lee Jones and Tom Waits” and songs with influences from New Orleans and alt.country, concluding “Rubble is a musically cohesive album threaded through with jazz phrasing and one that seduces and charms in a way only an expansive talent like Kāren can.”

Again, the praise kept coming. Steve Scott in the Waikato Times described it as “one rough-cut gem of an album”; Scott Kara in the New Zealand Herald made the comparison with Inside Outside saying “Rubble is refined, more consistent in musical mood and more accessible ... 12 tunes which are catchy yet gritty” and Mike Alexander in the Sunday Star Times concluded it was “almost the album she was born to make”.

At www.elsewhere.co.nz I observed Hunter was “alt” long before there was “alt”: “Kāren Hunter is one of a kind, and this album is further proof of that”.

Three years later she released Words and Groove, again with jazz musicians Samsom, Coddell, pianist Kevin Field, Manins, trumpeter Kingsley Melhuish and others.

At the time I wrote, “This new album completes the transition [from Rubble] in songs which have a sultry jazz-cabaret feel (over drum, bass and sometimes piano) and throw emphasis on her speak-sing lyrics and narratives”.

Rubble and Words and Groove were turned into a cabaret show at the request of the Taupo Music and Arts Festival, which Hunter – who possesses a vibrant and enthusiastic stage presence – thoroughly enjoyed and says would have liked to have taken more widely: “I’d love to have done the Spiegeltent.”

But she didn’t have the energy to keep applying for arts festivals and funding.

By then she was teaching at the University of Auckland, bringing her hard-earned experience to a new generation, passing on her knowledge about touring and the industry which had now grown up around the students.

“But at one point I had that experience of teaching yourself out of the subject. I was always able to do the industry side of things as a self-taught survivor, not something I approached from a management perspective, and I also gave classes at MAINZ on touring, for example, because I’d done a lot of it.

“Things have progressed in the industry but in the 90s and early 2000s I’d taught myself.”

“Things have progressed in the industry but in the 90s and early 2000s I’d taught myself.”

However, among the feedback she heard from students was what they expected out of being in pop music: “They wanted to be famous! I found that quite hard because I do it for a different reason. I couldn’t engage with that premise so was glad to let it go [in 2010] and did something different.”

Again, it was an extreme change of direction and into another kind of life.

She met two young Chilean brothers – Felipe and Marcelo Lopez-Betancourt – playing at 121 Café in Ponsonby (“like Tool on acoustic guitars, passionate, usually in tune and mostly in time”) and they reminded her of the passion she was missing, that deep yearning for something that would reignite her.

“When I left uni I had a feeling of ennui. At uni I was buying my water and shopping at Harvest, doing the marking ... and when I finished working there I had seven guitars, including four Ovations and two Les Pauls, and God knows how many amplifiers, pedals and all this gear. And I sold it all. I didn’t need any of it and found I could have more fun with less stuff. So we [her, the brothers] went on the road. We were busking, traveling around a van, doing festivals in 2011 all over the country.”

The brothers had been in the heavy metal rock band Postuma “with odd time signatures” and the trio called themselves Fear is the Enemy: “We were loud, frightening for people, very provocative and intense. We would play and sing in unison so it was intense and loud and political.”

At the end of that year a large group of fellow travellers went to Chile: “Lots of street performances, traveling on buses and trains, getting permission from café owners to play, get some money and move on.”

By 2012 they were in Bolivia and Peru, the following year Europe. Hunter had found her passion again. But there was a further path to be taken ... and it was inward.

Throughout her diverse catalogue of deeply personal songs – some directly addressed to family and friends – themes of spirituality had been common, and for the past decade she has been on an intense journey of music for healing and spiritual connection with the cosmos. “Spirituality is in everybody and there are times we know about it more than others. For me it was on a full moon or by the ocean when the planet itself would hit me like, ‘This is all there is, this carbon-based life-form will all soon be back in this earth.’”

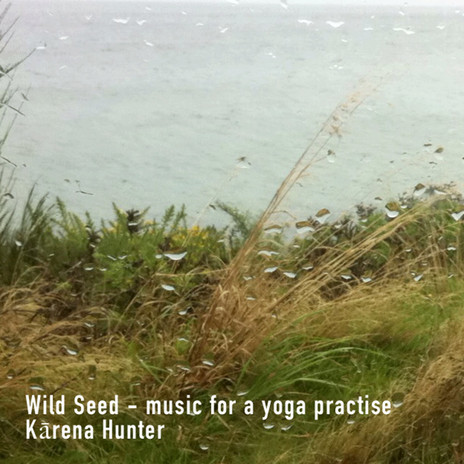

Hunter admits to having had degrees of depression all her life – as so many musicians have experienced – but for her spirituality is the flipside. She’d been practising yoga since the 90s and began to learn kirtan singing, a devotional Hindu style. Her song ‘Purify’ on Words and Groove opens with a passage of kirtan singing.

Looking back she says, “university was the peak of something and working my way towards a version of me creating a certain stability and credibility. You’ve got your flat or house, you felt credible, all of that ... but it didn’t make me happy. I always had a feeling there was something more.”

So today she is exploring spirituality and healing music, does sound journeys and guided meditations for various groups at festivals and concerts, makes astrology readings, and – by being older than many of those she works with – feels the responsibility to be a role model.

“I’m exploring a different kind of music and have different goals now. Happiness exists in the heart. I’m not involved in any organised religions but have a lot of respect for many.”

She laughs about a period of religious study she did and being told if she wanted to progress to the next level she’d have to become heterosexual.

You can almost hear the echo of her laughter at that Australian comment about The Private Life of Clowns: “But I just wasn’t able to do it. No, no, no.”

She is currently living on Waiheke (the sound of tūī as we talk is almost enjoyably intrusive) where she teaches music, and – after immersion courses in te reo Māori and Māori spirituality – has invariably been led to researching her own Celtic ancestry, pagans and druids. She’s fascinated by the idea of ritual and ceremony (“they make me feel good, feel magic”) and travel to Brazil is certainly on her bucket list.

Given the many different terrains, backroads and small corridors explored, and the often unpredictable turns her life and music has taken – she even forgets to mention she was in a TVNZ choir for a year at 13 and taught guitar at Mt Eden Prison for a year when 28 – it seems almost perverse to ask Kāren Hunter where she sees herself in five years, especially since she’s just said she’d like to live in every part of New Zealand.

“I imagine I’ll be involved in music with passion and expression, and it will never be boring to me. There will be songs and ceremony and passion and mystery and shadow and darkness. Whatever it is, there will be a discovery and emergence.”

You can’t doubt that.

--

Read more: Songwriter’s Choice, by Kāren Hunter