He was banging pots, pans and anything drum-like from an early age, played drums in the high school brass band and there were lessons from Barry Simpson, a drummer with the Radio 1ZB big band. Hopkins left school at 15 for a stint as a farm hand at Ōtaua in the Far North, one of several short-lived jobs, and his first professional drumming gig, at 16, was playing “soft dinner music” in a trio at Back of the Moon, a West Auckland restaurant. At 17 he was flatting in Parnell with a young pianist named Mike Nock.

Jazz would be Tony Hopkins’ music of choice in the years to come.

Although he displayed proficiency in a variety of styles, jazz would be Tony Hopkins’ music of choice in the years to come but, like many musicians of his age group, it was rock’n’roll that gave him the bug to play.

In January 2001, interviewed for Radio New Zealand’s Musical Chairs, Hopkins told Chris Bourke, “One of the things that really got me going was I went to see a film called The Blackboard Jungle with Bill Haley and the Comets. And it started off in the credits right at the beginning of the film: ‘Di dum – one two three o’clock four o’clock rock’. Ooh this is pretty wild. I went off to the theatre on my own, and was knocked out by the band.”

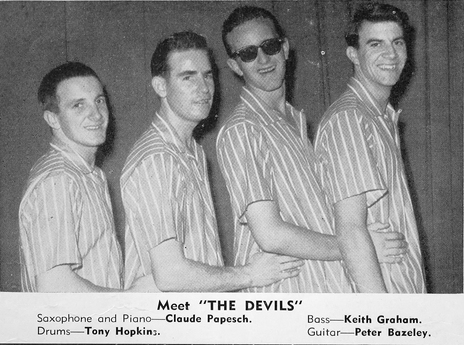

In 1958 Hopkins was in a short-lived group called the Microgroovers, featuring bassist Keith Graham. He told me in 2011, “I still didn’t think of music or drumming as a livelihood but it was such good fun.”

In November 1958 all that changed, not the fun but the livelihood. Hopkins and Graham were recruited to back Johnny Devlin on his action-packed nationwide tour.

Hopkins, ever ebullient, often played the drums standing, circling his kit without missing a beat, and earning a reputation as the tour prankster. When Johnny Devlin and the Devils crossed the Tasman in May 1959, they attracted full houses, enjoyed hit records and appeared regularly on television. The future looked rosy but Tony Hopkins wasn’t entirely happy. He told Bourke, “I became a little sick of the simplicity of rock’n’roll – I like the freedom to create that’s in jazz, that isn’t so much in rock’n’roll.

The money was still very much in playing pop and rock’n’roll.

Hopkins was flatting in Kings Cross, reunited with Mike Nock, then making a name for himself as a young buck to look out for. There were other jazz musicians in the household, notably American saxophonist Bob Gillett, who was to have a huge influence. Tony Hopkins’s switch to jazz had started but the money was still very much in playing pop and rock’n’roll. He was a call-on guy for occasional television appearances and any acts lacking a drummer. Promoter Lee Gordon had noted Hopkins’ prowess, employing him to back many of his touring acts, including Fabian, Sal Mineo and Tab Hunter.

Hopkins returned to Auckland in 1960, but only briefly, playing at Montmartre and Picasso, part of a growing jazz circuit in the city. Later that year he caught a boat to Hong Kong, working for his fare as a deck hand. Again, in Hong Kong the job offers came easy. He played regularly and even produced a weekly radio show, Six O’Clock Rock, sponsored by Coca-Cola.

But the lure of Auckland’s growing jazz scene was strong; by 1962 he was back in Auckland.

Hopkins was almost immediately recruited by pianist Mike Walker for a residency at the Montmartre café and within weeks who should turn up for a blow but Bob Gillett. Inspired by the high level of musicianship among Auckland’s jazz set, Hopkins then started Sunday afternoon jazz workshops at the Bali Hai Coffee Lounge with Walker and Gillett, plus bassist Neville Whitehead and tenor saxophonist Brian Smith.

Partly inspired by Charles Mingus’s jazz workshops, these Sunday afternoon sessions attracted Auckland’s established jazz players while budding musicians, instruments at the ready, would wait patiently for the nod to show off their chops, and the workshops gave rise to a new generation of jazz musicians.

Although generally credited with being the mainstay behind the jazz workshops, Hopkins cited Bob Gillett as the greatest innovator. “Bob was always striving for new sounds,” he told me many years later, “and he encouraged us all to follow suit. It was Bob who advised me to try adding pots and paint tin lids to my kit, and he once suggested that I use four-inch nails in one of my cymbals to see what it sounded like.”

Hopkins stayed in Auckland throughout the 1960s but he became increasingly disillusioned with the musician lifestyle. He had become a born-again Christian in Hong Kong and, now married with four children (including future vocalist Kate Hopkins and saxophonist Tim Hopkins), he concluded that a clean break was required. The family shifted to Sydney in 1971. Although he enjoyed a four-nights-a-week residency at The Top Of The Treasury in the Intercontinental Hotel and he was still on-call for the occasional tour, after two years he made a complete break, shifting the family to Brisbane. There were occasional Christian-based musical projects involving his church but Tony Hopkins all but turned his back on the music industry for 20 years.

Hopkins returned to Auckland in 1990 and threw himself back into the music scene.

Following his divorce from Claire, his wife of almost 30 years, Tony Hopkins returned to Auckland in 1990 and threw himself back into the music scene, spending four years as musical director at the London Bar, mostly playing with pianist Phil Broadhurst and bassist Kevin Haines. In 1993 the trio picked up Best Jazz album at the NZ Music Awards for Broadhurst, Hopkins, Haines – Live At The London Bar (Ode, 1993). He also performs on the Chris White and Aaron Nevezie Quartet album Take Me With You (1997, winner of the 1999 award), and appears on Nathan Haines’ Shift Left, recipient of the 1996 award.

There were other gongs. In 1997 the radio series Off The Record: The Kiwi Jazz Show, funded by NZ On Air, won best light music programme at the 1997 NZ Radio Awards. Hosted by Hopkins, a total of 52 one-hour programmes was produced by Andrew Dubber. The series remains an invaluable record of New Zealand jazz in the 1990s.

The London Bar hosted almost every name player in New Zealand jazz and Hopkins became a regular at New Zealand jazz festivals, playing with everyone that mattered, and encouraging young up-and-coming players like Nathan Haines, Dixon Nacey and Mark de Clive-Lowe.

In the mid-1990s, Tony’s son Tim Hopkins, having already made a name for himself in Sydney, regularly played with his father in Auckland. Tim Hopkins: “My father’s energy never ceased to amaze me. We would play the London Bar from eight till midnight and then head down to Cause Celebre and play until five am and Dad would be on top of it all night long.”

He Earned a reputation as Auckland’s oldest teenager, always energetic, always enthusiastic, always smiling.

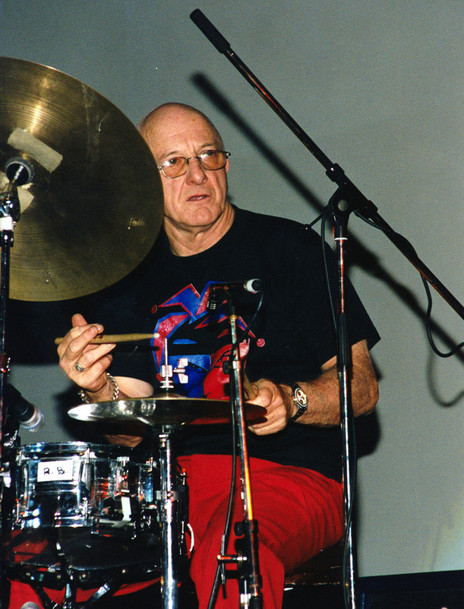

High Street venues such as Cause Celebre and Deschlers seemed unlikely places to find a seasoned musician in his fifties, but playing with younger musicians and sometimes adding hip hop into the mix, Tony Hopkins earned a reputation as Auckland’s oldest teenager, always energetic, always enthusiastic, always smiling.

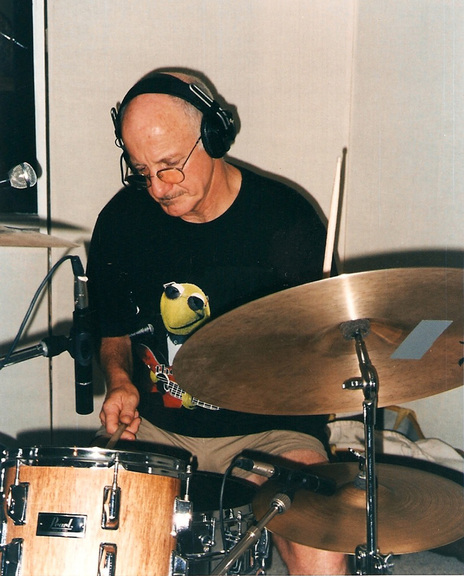

Tony Hopkins’ favoured jazz style had been be-bop but he extended those influences in later years. A fixture with Auckland’s community of Latin American musicians and dancers, in 2005 he formed a group of Auckland-based musicians to perform at the Guaramiranga Jazz Festival in Brazil, reportedly receiving an enthusiastic response. He developed a love of reggae and would sometimes leave his kit in mid-song to skank around the stage. Auckland’s oldest teenager indeed.

There were other highlights. In 2010 there was a national tour with Georgie Fame, followed by a tour of New Caledonia with famed Hammond organist Michel Benebig. When Doug Jerebine returned to New Zealand after 30 years away, Hopkins jumped at the chance to play together.

In the 2000s Hopkins played in the Grand Central Band, resident at the Grand Central bar on Ponsonby Road. A late-night bar, it was high energy from start to finish. The drummer was closer to 70 than 60. Tim Hopkins says, “I’d see him some nights at Grand Central, playing till dawn, and he’d resemble one of those old draught horses, beat but not giving him up. He’d look so weary some nights, covered in sweat but enjoying every minute.”

In October 2012, shortly after being diagnosed with inoperable cancer, the Variety Artists Club of New Zealand awarded Tony Hopkins its Scroll of Honour. He died on 4 January 2013.

In August 1999, Tony Hopkins was interviewed by Luke Casey for NZ Musician: “I’m big on swing and I play with a lot of energy, emotion and feeling. I like to think that people pick up on the feeling of my playing rather than my expertise or technique. I want people to feel good, to give them an escape for a while.”

Hei maumaharatanga ki te tino hoa me rangatira ...

--

Read more: Auckland Jazz - the Cappuccino Years, 1990-2000