You could say that he has created his own brand of art music. And yet Dudley Benson’s first influences were commercial pop radio, to which he was introduced as a pre-schooler by his teenage sister.

“She was really into Kylie, Jason, Michael, Madonna,” he remembers. “Their music really appealed to me – not just the music but the pop iconography and delivery too. So, when I turned five in 1988, all I wanted was Kylie’s debut album on cassette. Thankfully my parents came through. I was obsessed, and always listening and singing along to super cheesy radio pop. I knew everything in the charts, and was always nattering on to people about pop stars and their various views or scandals or relationships. I was like a child reporter for MTV! My punishment when I was naughty was my mum putting my [copy of Madonna’s] The Immaculate Collection on the top of the fridge. So yeah, that extreme radio pop was what got me onto the idea of being a musician. I remember being shocked when my mum told me that if I wanted to be a pop singer, I’d have to write the songs too. ”

The songs would come later, but initially his musical proclivities led him to choral singing; as a member of his primary school choir and then, at age 10, joining the Christchurch Cathedral Choir. Rehearsing and studying singing for around 20 hours a week, the young Dudley learned how to sight-read, how to blend, and ultimately how to be the soloist.

“I’m so grateful, not just for the technical musical skills I learnt, but for the ability to be relaxed as a performer. I don’t usually get nervous performing; I feel pretty comfortable in that energy exchange between an audience and a performer.”

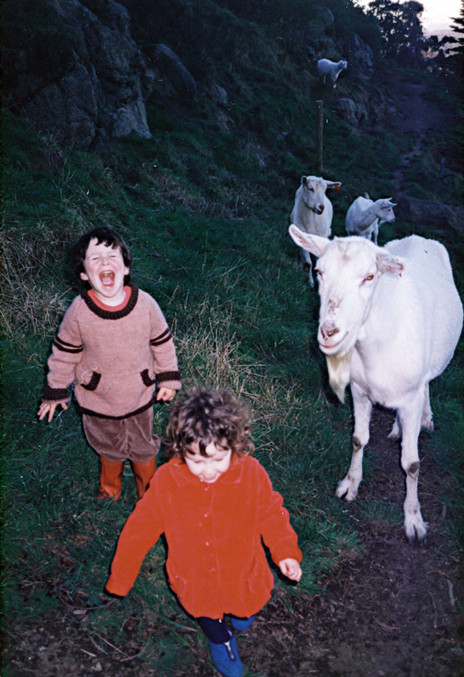

Dudley’s songs are filled with glimpses of his Christchurch childhood. On his 2008 debut album The Awakening, he sings of roaming “on the golden hills that cradled Canterbury”, singing to himself and communing with his “friends”, the family’s goats – “white quadrupeds eating lucerne leaves”.

But if such images are bucolic and idyllic, there are shadows here as well. In ‘Asthma’ memories of his Golden Retriever running in the hills dissolve into thoughts of what might have caused the asthma he suffered from as a child. In ‘It’s Akaroa’s Fault’ he creates a gothic poem – “a canon set in purgatory”, he calls it – from his childhood obsession with the murderess Minnie Dean, who would transport dead babies in hatboxes on trains and is the only woman in New Zealand to have been hanged. And in ‘Lingeress’, the haunting final track, he contemplates an absence, a silent presence, and “the ghosts that I’m a part of” that “follow me around”.

“When I wrote [my first album] I was 21, 22, 23, and felt like I had things to share about myself then,” he explains. “Particularly I was going through a period of nostalgia for my childhood, and thinking a lot about my ancestors. Really it was all a kind of delayed grief around my mum’s suicide in 1998 when she was 44, and I was 15. In these years I couldn’t directly address her death in music – I just didn’t know how. Instead, I skirted around it, and wrote songs about growing up on the Port Hills, having asthma, feeling haunted by a ghost, that kind of thing. But they’re all true and honest feelings and memories.”

The album looks back even further, to his ancestral heritage. In ‘Willow’ he sings of his great-great-great grandfather, Etienne Francois Lelievre, a celebrated colonial settler who travelled from Normandy to Akaroa on Banks Peninsula in 1836. He brought with him cuttings of willow trees from Napoleon’s grave on the island of St Helena, which he kept alive in a potato on the ship and transplanted in Akaroa. Cuttings from those trees can be seen on the banks of the Avon to this day.

Over three albums his music has moved from the personal to a focus on the whenua and manu.

It is not a song he would write now, he says, at least not in the same way. Over the course of three albums – The Awakening, 2010’s Forest and in 2018 Zealandia – his music has gradually moved from the personal to a focus on the whenua and manu, and most recently an exploration of nationalism and “how it is that through colonisation we got to where we are now”.

From the Port Hills to The Awakening was a journey in itself.

The Cathedral Choir wanted Dudley to delay his secondary schooling and stay on for an extra year as their soloist, but he had already had enough. An aversion to the Anglican prayers and sermons didn’t help. “Something I’m proud of myself at that age for, is that I always felt the doctrine was boring, illogical, and made no sense. The preachers were all so dull, and what they had to say really wasn’t about connecting to young people. It all felt very dated and very English.” His parents had to fight a contractual obligation in order for him to leave.

Dudley spent his teenage years idolising Björk. “It’s no accident that I got into her music right after my mum died,” he says. “I needed something to obsess over.” Though he wasn’t yet writing his own songs, after finishing high school he enrolled in composition at University of Canterbury, committed at least to the idea of being a songwriter. The course forced him to write as well as perform for other students. The first piece he wrote and played was called ‘Seven Days’, an electronic version of which ended up on his first EP and later evolved into ‘Willow’. But while the course helped build his confidence as a performer and writer, he found the composition department was more focused on avant-garde sonic art and contemporary classical than servicing songwriters.

Enter Tilda Swinton. At the end of his third year he landed a summer job as an extra on the set of The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, the Andrew Adamson-directed Walden Media/ Walt Disney feature film, starring the British actress as the White Witch and largely shot in Canterbury. “I didn’t really seriously audition, I just went along to support a friend, but they ended up calling me back and for five weeks or so was running about in bright green spandex pants and prosthetic makeup, sometimes being chased by a gigantic imaginary rhinoceros.

“Anyway, I met Tilda Swinton and gave her a little EP of what I’d made at university. She ended up playing it and, probably just to be nice, she said she liked it. She invited me to a party that night at her cabin, where she advised me to leave Christchurch. I took that seriously and moved to Auckland about a month later.”

Arriving in Auckland in early 2004, he enrolled in a year’s course in pop songwriting at the University of Auckland, found a flat in Grey Lynn, and fell in with a likeminded group of musicians, writers and visual artists. Working at Marbecks Records, he formed relationships with people who taught him about the music industry.

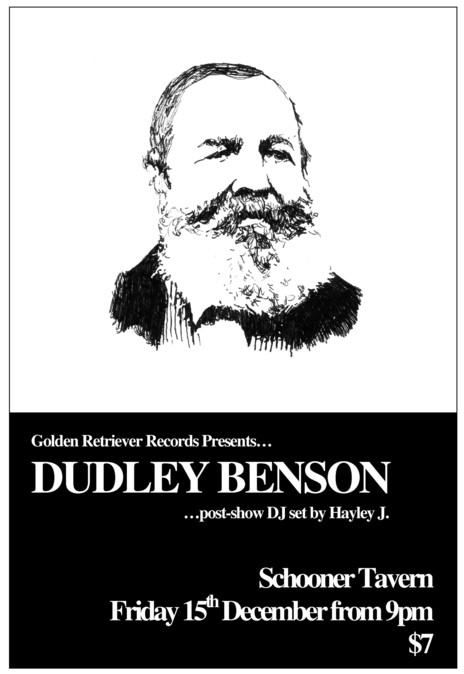

In 2006 he started his own label, Golden Retriever, and began to release music in limited editions. Two EPs, Mushrooms & Toadstools and Steam Railways of Britain appeared on CD, and included the first available versions of what were becoming signature songs in his live set, ‘It’s Akaroa’s Fault’ and ‘I Don’t Mind’.

With the beginnings of an audience in place he began playing his first solo shows “on a keyboard, with backing tracks on a dodgy iPod”. Those early shows were mostly in bars and clubs: the Odeon Lounge and Dogs Bollix in Auckland, Wunderbar in Lyttelton, and San Fran in Wellington where he opened for Animal Collective.

There were overtures from a couple of record labels. He found himself being taken out to dinner and offered deals. “It’s hard for me to believe now that for a while there, elements within the music industry were interested in my work,” he says. “Kind of ridiculous because that was never going to work, but I did like French Onion soup so …

“Generally they didn’t like taking risks though, and it was only when they saw other people enjoying my shows that they decided there could be some value in my music. I never seemed to gel that well with label people. I would often be spoken to like I was a curiosity, or not entirely to be taken seriously. I once got my own EP artwork mansplained to me by a distributor.”

Independently he began to put together the framework and resources to make The Awakening, which involved – in addition to his own voice and keyboards – a nine-piece choir, string and recorder quartets, and taonga pūoro.

“I needed to bring people into places where the focus could be completely on the music.”

He had by now realised that bars were not the best environment for his music. “I loved those shows, but sometimes you’d have just one drunk person ruining it for everyone, and I felt like I needed to bring people into places where the focus could be completely on the music.” So to support the release of The Awakening he embarked on a tour of churches, accompanied by most of the ensemble he had assembled for the album. Featured on both the record and at some of the concerts were karanga manu: instruments imitating the songs of native birds, played by taonga pūoro maestro Richard Nunns.

Nunns would also contribute to Dudley’s next project, for which Dudley immersed himself in the songs of Nunns’ closest collaborator, Hirini Melbourne, the prolific Māori songwriter whose waiata, all written in te reo, had for decades been sung in schools, at protests, on marae and in concerts all over the country.

Dudley had become aware of Melbourne, who died in 2003, during his time at Marbecks Records when he began to notice “interesting people” bringing his CDs and collaborations with Richard Nunns to the counter. He soon found himself immersed in Melbourne’s waiata. “I loved everything about them. His voice was like the earth to me, I found the pared-back approach of just guitar and voice so easy on the brain, and of course the songs themselves focused on birds, trees, insects.”

The idea for Forest: Songs by Hirini Melbourne crystallised for Dudley during a trip to Rakiura/ Stewart Island in 2008. Walking through Te Wharawhara, the island bird sanctuary, he was shocked by the lack of birdsong. “In that moment, it really highlighted to me the plight our wildlife was under, and Hirini’s bird waiata suddenly gained so much more weight. It was that day that I decided, if Hirini’s whānau would give me permission, I would record my own versions of his waiata to help share his stories of our birds.”

In preparation for recording the album he returned to the University of Auckland for two years for a foundation introduction to te reo, as well as to study Māori politics and contemporary indigenous issues.

Released in 2010, Forest placed the focus almost entirely on the human voice, with Dudley’s vocals supported by a vocal quartet and beats supplied by human beatbox champion King Homeboy. As well as Richard Nunns’ taonga pūoro, there are the birdcalls of Franz Josef Glacier bird mimic Gerry Findlay, and for one song, ‘Tui’, the exquisite singing of veteran British folk artist Vashti Bunyan. Dudley had sent her a copy of The Awakening because her delicate music had helped inform its sound. She wrote back and agreed to sing on the duet.

Forest was followed by a national tour of halls and marae, for which Dudley was joined by vocal quartet The Dawn Chorus, Australian-based beatboxer Hopey One, and dance artist Cat Ruka. A scenic backdrop was painted by well-known artist Nigel Brown.

In 2012 Dudley spent two weeks as artist-in-residence in the southern Japanese city of Kurashiki, where traditional music and arts are a core part of daily life, and produced a programme for Radio New Zealand in which he spoke to musicians there about their instruments and traditions.

Back in Aotearoa, the issues and discussions he had become involved in during his Māori studies continued to permeate his work, and his third and most elaborate album Zealandia began to take shape, though it would be eight years in the making. “That record required a lot of reading, talking, learning – particularly at the University of Auckland’s Māori Studies Dept – I got my degree from there when I was 27 and am so proud of that. Classes in Māori Politics, International Indigenous Issues, te reo – they all informed Zealandia.

The song ‘Birth of A Nation’ addresses how Pākehā, or colonisers, “now need to de-colonise ourselves.”

At the heart of Zealandia is the concept of decolonisation. In the song ‘Birth of A Nation’ he addresses how Pākehā, or colonisers, “now need to de-colonise ourselves. To fully acknowledge our shared histories, accept what our ancestors seriously messed up, how our current systems and institutions continue to be racist and colonising. I don’t think it’s impossible, and I guess like so many movements towards progress, it starts with teaching our children.”

The music shimmers, shudders, whispers, and roars. In addition to Dudley’s synthesisers and voice – sometimes multi-tracked in richly layered harmony, other times intimate and confiding – are instruments not often found on pop recordings: harps, harpsichords, bagpipes; Alistair Fraser is credited with playing pieces of limestone, obsidian, columnar basalt and petrified wood, and that’s not to mention the full artillery of the New Zealand Youth Choir and Dunedin Symphony Orchestra. In addition to the sheer intricacy of the compositions, another reason the album was so long in production was the time it took to raise the necessary funds to hire the arrangers, conductors and musicians.

By the time Zealandia’s long gestation had begun, Dudley had moved to Ōtepoti/ Dunedin. “I’d toured in Dunedin and felt it had a great energy and heaps of potential as a city. It was a lot more affordable than Auckland, and still is, and the people are quite different. I notice when I’m in Auckland that the wealth disparity is intense. People are so ready to show off their flash cars and flash houses, while someone homeless is sleeping outside. I find that deeply problematic and I don’t want to be around it. In Dunedin there’s far less materialism, you couldn’t get away with that.

“Musically the community is very solid here. It’s much more about the process than the delivery. People respect you as a musician here depending on how you go about making your work, and how you commit yourself to your mahi toi, rather than how many plays you might have on Spotify.”

Though he played some shows in Europe in 2019, Dudley never took Zealandia on the road as he couldn’t see a way to perform the material live without a huge budget. Not that his approach to touring had ever been particularly viable. “I don’t really like repeating a show much, so I end up only getting one tour or show out of a single approach. It means I end up spending months working on one show, never to be done again.

“I’m very much a part-time artist, and I’ve been lucky even to be able to do that. I’ve usually always had a part or full-time job and fit my work around that. Though I’ve learnt how to get funding and residencies from government arts schemes of various kinds, I don’t really think that the system is set up to accommodate an artist like me – I can’t pump out work regularly. And I don’t like repeating live shows. My few friends who have been able to do this I really admire, but they are constantly having to deliver work or performances, and I’m not capable of that. There just aren’t enough people in Aotearoa for music of my style to provide financial support.”

For the last few years he has co-run a bar in Ōtepoti called Woof!, and fits his music-making around the long late hours. Though still deeply concerned with issues of nationalism and the environment, these subjects may not feature as prominently in his next songs. “I feel that side of my work has said all it can for now, and I’m moving into a more personal space again, focusing on sexuality and matters of the troubled heart – scary! I have never felt my life is interesting enough to want to be too candid about love, but I think finally maybe it could be.”

He enjoys DJing, and will occasionally throw one of his songs into the set, which he sings along to. Though music, he says, is not “helping me pay my way through the world” it continues to help him “understand who I am and find my place in it”.