In 1973 Reece Kirk, along with future Airlord bass player Brad Murray, recruited Mackenzie into a trio named Friends. Kirk was enamoured of the then in-vogue Californian singer-songwriters and aimed to emulate the harmonies of Crosby Stills and Nash. In their short lifespan Friends released two singles, placed third in the finals of New Faces in 1974 and performed various concerts around New Zealand.

In early 1975, Mackenzie and Murray left Friends and, over a two-year period, slowly pieced together Airlord in Wellington. Mackenzie wanted to retain the harmonies from Friends but set them in a full-blown prog rock band. Originally named Outlord, the similarity to American group The Outlaws caused a rethink. The band rehearsed relentlessly, endured multiple line-up changes and played gigs at venues such as Ziggys, The Royal Tiger Tavern, and Victoria University. Other one-off gigs included a Wellington concert with Billy TK’s Powerhouse and an open-air show in Otaki supporting Roy Orbison.

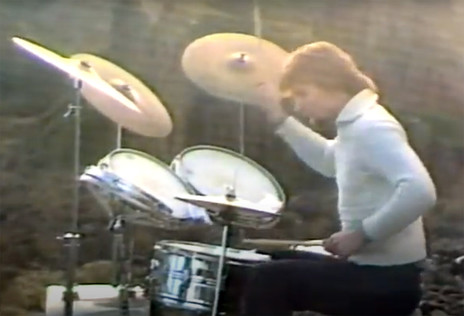

Having run through 40-plus members, and after an attempted but aborted relocation to Auckland, the line-up eventually settled with Mackenzie on vocals and guitar; Brad Murray, bass; Ray Simenauer, guitar and vocals; Alan Blackburn, keyboards; and Rick Mercer on drums.

“Brad and I had seen Ray playing in a blues band at Ziggys, a club owned by Edd Morris, who we knew through Reece Kirk,” says Mackenzie. “Rick, originally from Nelson, successfully auditioned after responding to a press advert. Alan was last to join – he’d been playing in pub-rock band Tramp in Paekakariki.”

In late 76 Airlord appeared on the TV programme Grunt Machine. “We were paid a fee for our appearance,” says Rick Mercer, “and spent it on recording, so we could mime our track as we didn’t trust the TV sound people.”

Airlord sailed to Sydney on a rusty old Russian ship, berthing at then-grotty Darling Harbour in early 1977.

“We also recorded demos at a studio in Upper Hutt,” says Mackenzie, “and hawked them to the two big record labels that were then based in Wellington, EMI and Phonogram. There was no interest from EMI, but Phonogram sent an A&R man to several of our gigs that eventually lead to them offering us a one-off single deal. Just as we were about to sign however, they had a change of heart and withdrew the offer. We decided instead to try our luck in Australia. As we were set to leave, Phonogram changed their mind once more and re-offered the deal but by then it was too late. We sailed over on a rusty old Russian ship, berthing at then-grotty Darling Harbour in February 1977.”

Blackburn recalled the band making wooden packing cases for all their gear but keeping his precious Model D Minimoog safely tucked in his suitcase.

“We all crammed together into a flat in Bondi,” says Mackenzie, “then one of Sydney’s cheaper suburbs. I had my chef’s ticket from an earlier stint in the Air Force and landed a job at $90 a week at a seafood restaurant. I frequently brought home leftovers to feed the band.”

Blackburn also recalls that money was tight. “I remember once after a failed fishing trip we ended up eating the bait! We clubbed together what little money we had and bought a double-cab VW Kombi for getting around.”

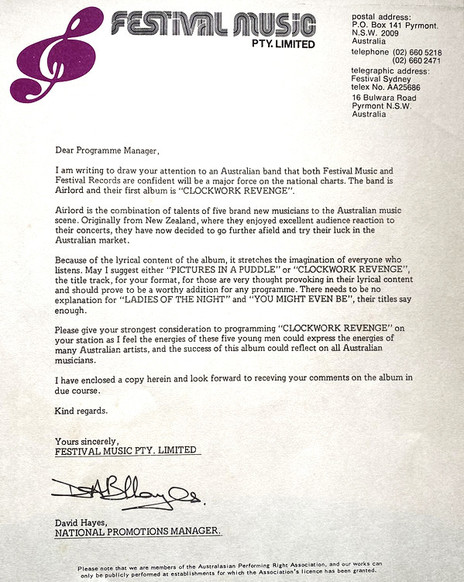

“Full of enthusiasm, we set up a showcase gig at French’s Wine Bar in mid-city,” says Mackenzie. “We sent out invites to the A&R departments of every record label we could find the address for. Despite lots of positive responses, come the big night only Festival Records sent anyone along. Martin Erdman, Festival’s in-house producer and A&R man, loved us and invited us to record some demos for his bosses to audition. It all happened very quickly – the gig was on a Friday night, by the following Wednesday we were in the Festival Studios at Pyrmont. French’s loved us too and asked us to return the following Friday. Erdman turned up again and the following week presented us with a recording contract, an album deal with a healthy royalty rate. We’d only been Australia for two weeks. Our heads were spinning!”

The band began recording almost immediately. Mackenzie: “Given that we had a full set of complex songs that we’d practised for months we were ready for the studio pretty much straight away. We were allocated Erdman as our producer. Engineer Warren Barnett did a superb job and painstakingly mastered the album to state-of-the-art sound quality. He told us he’d gone through three diamond needles cutting the acetate from the master tapes.”

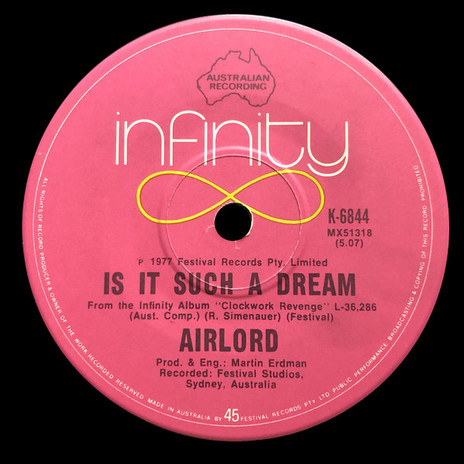

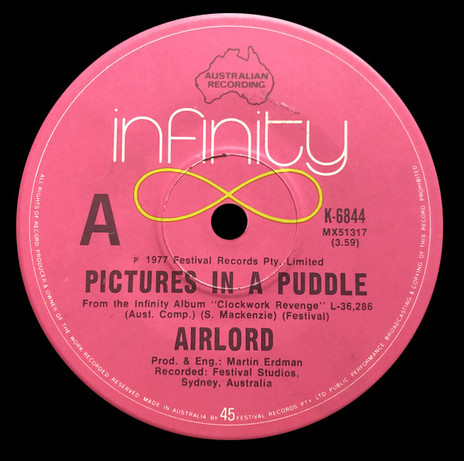

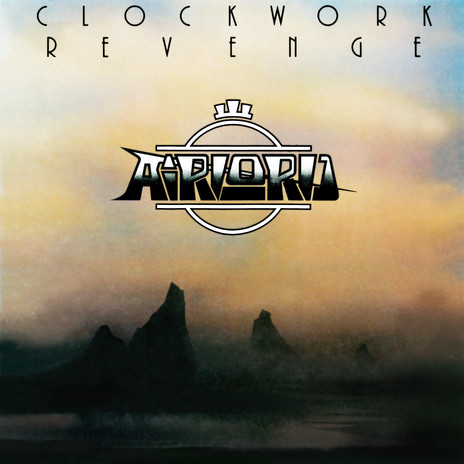

Befitting the prog-rock genre, the album Clockwork Revenge (1977) boasts just seven long tracks, three by Simenauer and four by Mackenzie. Lead vocals were taken by the songwriter in each case. Musicianship is of the highest order, with some spectacular guitar playing by Simenauer on show, and again in classic prog-rock style, plenty of keyboards.

Blackburn: “In addition to my Minimoog I had a Yamaha portable organ. Festival Studios gave me access to a Yamaha grand piano, a Mellotron and, from memory, a Fender Rhodes.”

In the title song of the ‘Clockwork Revenge’ LP, toys in a toyshop come to life and attack the owner.

Mackenzie: “Our goal was to get a lot of depth and moods into the songs. In listening back to the album now, I can hardly imagine what I must have been thinking in writing some of the lyrics – especially the title track (in which toys in a toyshop come to life and attack the owner). I have no recollection of it at all! However, I do remember it turned into the highlight of our live shows, we always ended with it.”

Reviewers at the time commented on the similarity of Mackenzie’s voice to that of Genesis’ Peter Gabriel. “There’s no doubt I was influenced by Genesis,” he says. “In fact I was positively obsessed with their album Selling England By The Pound. But I certainly never set out to imitate Gabriel, I always sang in my natural voice – apart from on the title track where I was depicting a toy!”

During the album’s recording the band was approached by Lori Balmer, a young Australian pop singer with Bee Gees connections who needed a backing band for a tour. The money was good, so the band accepted the offer and toured the eastern seaboard with her, supporting Cliff Richard. (Balmer later recorded with both Dalvanius and Collision).

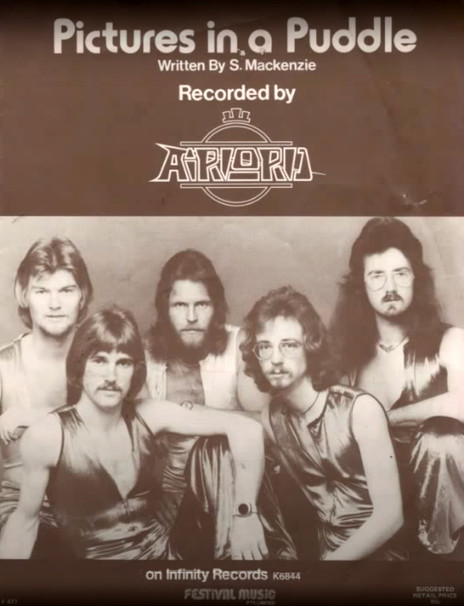

“After the tour we decided on ‘Pictures In A Puddle’ as our first single,” says Mackenzie. “Festival’s commitment showed no bounds; they printed T-shirts and commissioned a music video for the single. We all trouped off to Kiama, a rocky coastal location south of Sydney famous for its blowholes. The song is about a car accident, so the first part is filmed at the side of a country road. For the second part of the song we were lifted up on to the rocks via a cherry-picker – I recall it taking hours and half freezing to death as the winds whipped in from the sea.”

An excited Festival hosted a lavish listening party for the album, which was released on their “cool” Infinity label. The function, at the Festival Recording Studios, saw the place turned into a mock-up of a 747. Attendees were issued “airline” tickets and the band acted as drink trolley waiters. Tannoy announcements were made for the audience to fasten their seat belts and a smoke machine was employed to create atmosphere as the album was given a full playback.

Festival then bankrolled two launch gigs at the historic Elizabethan Theatre in Newtown, an inner-city Sydney suburb. No expense was spared. An elaborate hand-painted backdrop was prepared, the best sound and lighting firms were engaged, and six dancers contracted to supplement the band’s performance. The band had special costumes made. A voiceover was created that linked the songs in a rough chronological sequence based on the lyrics, starting with the medieval-themed ‘Ladies Of The Night’ and ending with the space-travel song ‘Earthbound Pilgrim’. All up the label spent nearly $20,000 per show on the launch. The first gig attracted an audience of 1000, at least a third of which were music industry insiders. The gig was a massive success, the audience calling Airlord back for four encores and giving them a standing ovation. By then they’d played every track they knew.

For the launch gigs at Sydney’s historic Elizabethan Theatre, no expense was spared.

The second night wasn’t quite a sellout but again garnered an over-the-top reaction from the crowd. Reviewers raved. The adulation had Airlord on cloud nine and imagining a very bright future indeed. What could possibly go wrong? They were about to find out.

“Festival had arranged a manager for us, Martin Bedford. He did a great job organising the launch shows,” says Mackenzie. “His plan was that we should now gig regularly, build up a fanbase. He signed us to the then biggest live booking agent in Sydney. The owner of a tiny wine bar in the outer suburbs had read one of the glowing reviews of our launch gig and booked us for a Friday night show for a fee of $400. When we got there, we found a stage so small we could barely fit the band on. The wine bar manager wanted to know where the costumes, dancers and backdrop were that he’d read about. No amount of explaining the cost of the launch shows was accepted and after the show he point blank refused to pay us. Bedford protested to the agency, but they took the side of the venue owner and immediately blacklisted us.

“The band was unaware of this until months later, but we were unable to rectify the situation. Things went downhill fast. Ditching our management, we took to managing ourselves, but found gigs hard to come by.”

“It was difficult to compromise our quite theatrical show to fit smaller pubs and clubs,” says Mercer.

Airlord tried to adapt their songs to a harder rock style to compete with the rapidly growing demand for the pub-rock sound. “We soldiered on for about a year but to be honest I was worn out by then,” says Mackenzie. “The lack of bookings, and therefore money to live on, made it nigh-on impossible to survive. The band slowly fell apart. Ray was the first to leave, followed by Brad. In the end there was just Alan and I left.”

Mercer: “Line-up changes and trying to modify our sound meant that really, the spirit of the original band was lost within a few months.”

Mackenzie and Blackburn formed the band Machine and, later, Silent Jets. When these broke up in the early 80s Mackenzie established a successful home-renovation business. He continued to write music and in 2006 under the name Mackenzie-Jones released the album A Rust Red Sky with his wife Jean-Ann Jones. The title track had earlier won Mackenzie the 2002 Singer-Songwriter Award from the Sydney Performing Arts Council.

“IN HINDSIGHT WE WERE JUST A LITTLE TOO LATE FOR THE PROG ROCK HEYDAY,” SAYS STEVE MACKENZIE.

Blackburn went on to spend 20 years in a covers duo before training as a Braille music transcriber, which he has specialised in since 2000.

Simenauer returned to New Zealand but was tragically killed in a road accident less than a year later, in March 1989.

Mercer turned his hand to radio and went on to a very successful career as the host of Loveline Dedications on Mix FM in Melbourne, with the press nicknaming him “The Love God”.

Murray also remained in Australia, pursuing his love of car racing, and local band management before passing away in 2017.

Having been bootlegged on CD in Japan and Europe, where the album has generated most interest, Airlord’s Clockwork Revenge was finally officially released digitally in 2020.“In hindsight we were just a little too late for the prog rock heyday,” says Mackenzie. “The late 70s saw the rise of Aussie pub rock, with Cold Chisel and The Angels epitomising what the punters wanted. In February 2017, myself Brad, Rick and Alan arranged a 40th reunion get-together at Darling Harbour.”